Visibility is a double-edged sword or, as French philosopher Michel Foucault once categorized it, “a trap.”1 The term’s duality is embedded in the definition of the word itself: “The state of being able to see or to be seen.”2 When considering possible implications of these opposite yet inextricably linked conditions, concepts of humanity and relationality quickly rise to the fore and are unavoidably joined, exemplifying not only the tensions inherent to the notion of visibility but also its inevitable entanglement with issues of power.

It is precisely such topics that seem to most interest Dr. Ashley James — associate curator of contemporary art at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, and the curator of “Going Dark: The Contemporary Figure at the Edge of Visibility.” James’s first exhibition at the museum, “Off the Record” (2021), included artworks from the Guggenheim’s collection that problematize and reconsider authoritative narratives imposed and preserved by historical records. The exhibited artists’ attention to the confluence of issues of memory, power, erasure, and identity in archival documents is aptly dovetailed by James’s subsequent project, “Going Dark,” which returns to and expands upon these themes from the closely related angle of visibility.

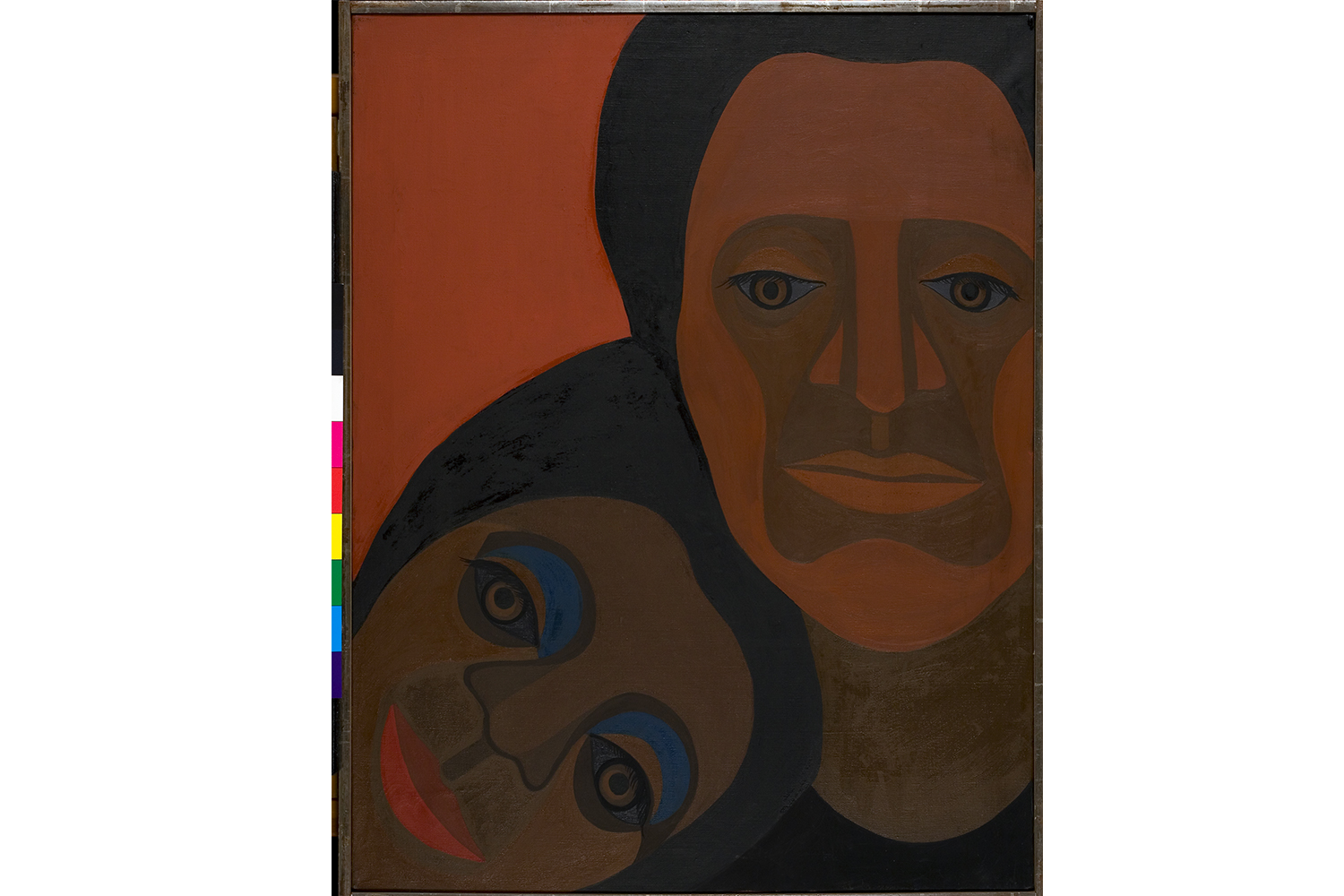

“Going Dark” examines the work of artists who employ formal tactics of concealment to strategically probe the contradictions central to visuality — namely the strain between longing to be seen and feeling unsettled by external perception. The exhibition features the work of twenty-eight artists, most of whom are Black and more than half of whom are women. These demographic details are noteworthy for a number of reasons. First, this exhibition occupies the museum’s iconic rotunda, a space where artists of marginalized identities have historically been underrepresented. Bringing this group the utmost visibility within the institutional context of the Guggenheim is a significant form of “curatorial activism” not to be overlooked.3

This grouping additionally emphasizes the centrality of issues of visuality in the lives and daily experiences of marginalized — especially Black — subjects, for which the act of being seen is particularly vulnerable, having the potential to impose dominance, discomfort, and even violence. The artworks in “Going Dark” evidence some of the ways those who are marginalized in society navigate, challenge, and evade external gazes. These methods include masking, disguise, erasing, and literal darkening. Martinican theorist Édouard Glissant’s proposition of “the right to opacity” resonates here, evoking an optical term in relation to identity and its politics.4 Within the context of “Going Dark,” opacity serves as an additional strategy through which marginalized artists establish command over the slippery dynamic between their coexisting desires to be seen and to remain invisible to hegemonic scrutiny.

As a condition of observing and being observed, “visibility” also speaks to a general audience, manifesting itself conceptually and practically in ways we are all too familiar with in our contemporary age. Today, the instantaneous generation and proliferation of images through cell phone cameras and social media applications is beyond commonplace. Technological innovations have rendered privacy virtually nonexistent and often undesirable in a world of constant visual access and exhibition. It is therefore unsurprising that photography plays a key role in “Going Dark,” starting with Ming Smith’s “Invisible Man” series from the late 1980s and early 1990s. These dimly lit photographs give a glimpse into Black life in Harlem during the 1990s through blurred, almost ghostly vignettes that exemplify photography’s ability to memorialize moments and subjects in flux. The details in Smith’s portraits are strategically in and out of focus, present but also elusive and haunting, playing on visuality’s unique contradictions.

As I rounded the rotunda’s ramps, I was puzzled by a looming surveillance ball dangling in the circular void. After relinquishing my phone to a locked pouch to enter a curtained-off area, the purpose of the dark orb beyond its evident conceptual links to the exhibition’s themes became clear. Inside, I discovered the surveillance camera had been filming visitors the entire time. From within the privileged space of the viewing room and without my usual third eye — my iPhone — the power dynamic shifted as I went from observed subject to surveyor. This installation becomes additionally meaningful when considering the Guggenheim’s Panopticon-like architecture, which enables a constant state of observation. The chosen name of the installation’s artist is also significant, speaking powerfully to the concept of “going dark.” A quick online search for “American Artist” will demonstrate their intent.

The artworks in “Going Dark” really do exist at James’s aptly titled “edge of visibility.” My phone’s camera lens struggled to capture them, producing overexposed or illegibly dark images, and the works eluded my own eyes too, with many features imperceptible from even a short distance. Zooming out, the interplay of the rotunda’s light rails and shadowy artworks confirm the depth and unity of James’s curatorial vision. Despite their diversity of makers, mediums, and time periods, the artworks on view and the exhibition’s conceptual ground could not feel more cohesive.