Like clouds, abstract paintings invite our own inferences and preoccupations, showing us what we want to see. Pushing against this with the ostensible goal of equanimity, critics, when writing about abstract works, frequently latch onto parsings of an artist’s biography or espoused conceptual or ideological framework. In discussing her own practice, Emma McIntyre explicitly disavows these strategies of reception. The New Zealand–born, Los Angeles–based artist makes abstract paintings that are self-aware, witty, and dense with art-historical references but intentionally murky with regard to the particular intentions of the individual who rendered them into being.

McIntyre’s paintings do reveal a keen observer of generations of artists who explored the edges of abstraction — and the possibilities of artworks to delineate them. This spare collection of seven oils on linen, which range in scale from intimate to six by five feet tall, are catholic in their references. In her canvases, she employs viscous, Frankenthaler-esque pours and patchy dry-brush strokes that call to mind Turner’s proto-abstract cloud studies, alongside imprints made from her own body and graphic red dots that rest tensely on several of the works’ surfaces. The artist’s Fuses (2020) was presumably inspired by the 1967 piece by Carolee Schneemann. In Schneemann’s vibrant, luxuriant film, the artist and her partner, composer James Tenney, are seen in close-up having sex, as recorded via semi-abstracted and manually scratched footage intermittently spliced with dreamlike montages — all presided over by Schneemann’s cat, Kitch (who is listed prominently in the film’s credits).

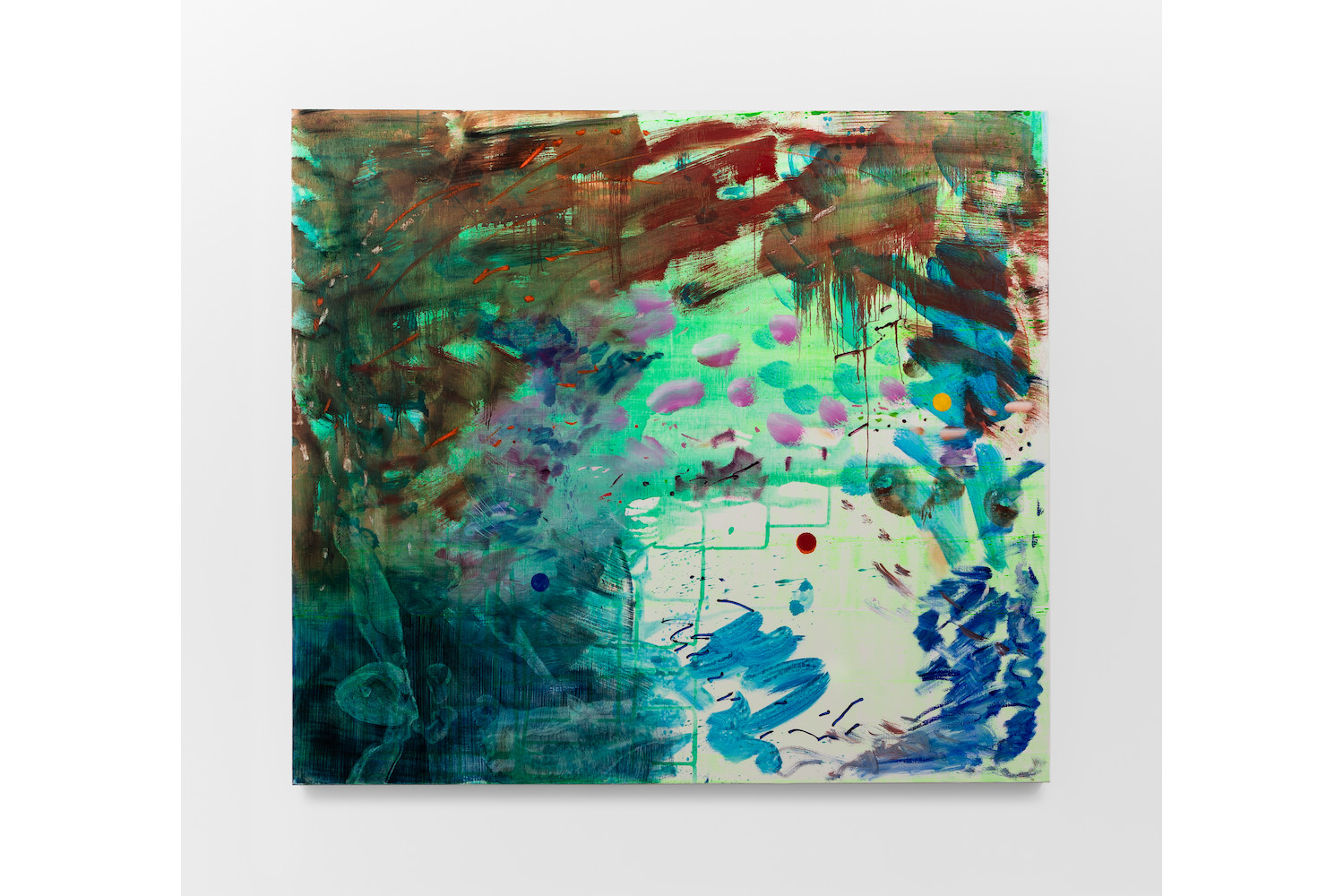

McIntyre has cited Schneemann’s work in the margins of abstraction and representation (to say nothing of her groundbreaking insertion of the carnal into 1960s performance art and, particularly, the boy’s club of 1960s structural film) as a significant influence on her practice. In another titular allusion, the younger artist’s Cythera (2021) references Jean-Antoine Watteau’s The Embarkation for Cythera (1718–19), which depicts a party of amorous aristocratic revelers on an island picnic as they begin to pair off, flocked by encouraging cupids. And a subtler allusion to eroticism can be seen in the adjacent Bathers (2020), which is dominated by a wash of cerulean and sea green and framed by a dense umber overhang looming in the painting’s foreground, as if the viewer was observing their subjects surreptitiously from behind a tree. The work’s title, composition, and mood call to mind Thomas Eakins’s subversively erotic Swimming (1885), in which lithe young men are depicted coyly from behind, bathing and diving in a swimming hole.

Sex is foregrounded within each of these works. But beyond that universal tug, the viewer is offered little of the artist’s own mindset. This choice is intentional. In this exhibition, McIntyre disabuses her viewer of the notion that she is responsible for defining herself. “Pour plenty on the worlds” is so crowded with points of entry and avenues to explore within the artist’s visual cosmos, with its vast spectrum of mark-making — from washes to resist techniques to oil-stick scrawls — and artistic references dotted throughout the exhibition’s press release, the works’ titles, and in her writing about these works, that one is at risk of getting lost. Rejecting the expectation of premeditated explanation, and particularly that artists who identify as female—or BIPOC, queer, or any other qualifiers for that matter— are required to address said status in their work, she instead chooses to operate in a realm where identity and narrative are fluid. And yet, I’ll admit that as a viewer I remain greedy for this context: for the backstory, for the motivation behind the act.