Donald Judd’s first retrospective in the US in more than thirty years — titled simply “Judd” — presents seventy of his sculptures, paintings, drawings, and prints. It spans the entire arc of Judd’s career, from his early paintings to his later enameled aluminum boxes. No matter the medium, the exhibition as a whole provides a clear sense of Judd’s truly radical artistic process; having someone else make your work, with no evidence of the artist’s hand and no expressivity, was unheard of in the 1960s.

But it wasn’t always that way. In the early ’60s, Judd was making abstract paintings. Untitled (1960) is a modest-size yellow oil painting with a whitish squiggly line running across it like a lone piece of spaghetti. While this work demonstrates playfulness, and having not seen a Judd painting before was a surprise entrée to the exhibition, other early works already foreshadow Judd’s future austere objects. Untitled (11-L) (1961–69) is one of twenty-six woodcuts on paper done in a red rhomboid shape reminiscent of a tuning fork. The three-dimensional version of this woodcut, along with the outcome of a couple of preparatory sketches, is also on view, revealing Judd’s methodical ideation process. During this time Judd published his essay “Specific Objects” (1965), in which he lays out his frustration with painting and sculpture and expounds his own aesthetic philosophy. Though not a Minimalist manifesto per se, many of the reductive techniques of the movement — whereby the artist carefully controls shape, scale, and materiality but does no fabrication — are outlined here.

By 1964, Judd had already begun making work that fulfilled the loose desiderata for “specific objects” (i.e., not painting or sculpture) described in his essay. Untitled, a large box of orange-pebbled Plexiglas and hot-rolled steel, sits on the museum floor plainly, while another work, also called Untitled from 1965, provides what might be Judd’s most well-known shape: a series of seven stacked galvanized iron boxes protruding from the wall. They lack the color and sleekness of Judd’s later “stacks,” but being a progenitor of that series add to the survey’s completeness.

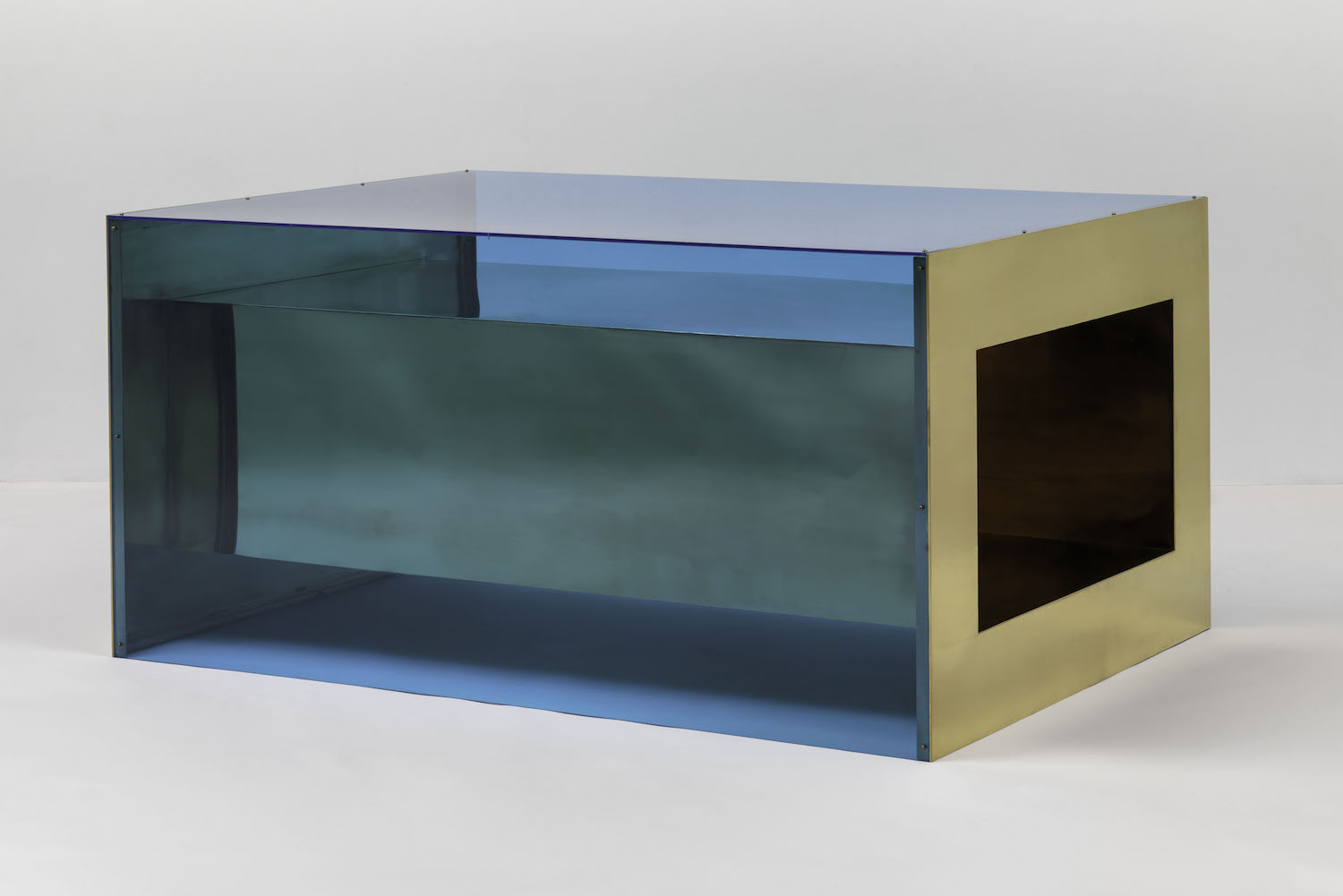

Throughout the 1970s and 80s, Judd produced work that would become known as Minimalism — a label the artist did not accept. Works such as Untitled (1977), a shelf-size open box of stainless steel with a red Plexiglas back hung on the wall at about head height, came to exemplify the movement’s aesthetic. In the 1970s, Judd also began to produce works made from plywood, such as the series of six open parallelogram boxes impressively sized at 72 × 143 × 72 inches. Lacking the lustrous production value of his metal and Plexiglas works, the plywood objects bear an approachability absent in other pieces, amplified by Judd’s plywood furniture dispersed throughout the exhibition. Present in all of Judd’s work, however, and an essential element of it, is the empty or hollow volume.

Empty space is circumscribed by Plexiglas, metal, or wood, allowing light and shadow to work their natural charm on the objects. How the colors, surfaces, and shapes of Judd’s specific objects interact with their environment provides the phenomenology of the viewing experience — vibrantly on view in the twenty-four-foot-long Untitled from 1991. It is here, outside of the artist’s ability to plot and define his work, that the magic of Minimalism happens, when the “plain sense of things,” to borrow a wonderfully ambiguous phrase from Wallace Stevens, radiates out to the viewer.