Sean Landers’s scrawl is the way into his peppery worldview: his forty-painting retrospective at Le Consortium often doubles as a reading exercise. The American artist takes notebook-style confessions but narrates them outside of their private confines. A critic once described his work as “performances posing as crises, balanced between self-knowledge and self-doubt,” while curator Eric Troncy likens Landers’s self-conscious expression — a kind of verbose interiority laid bare — to the stylization of social media. Sometimes his writing is circular, almost singsong (“When freedom becomes the cage / When the cage becomes freedom”). Other times it’s plaintive and makes the viewer flinch in recognition of shared burdens (“the saving grace is that the alternative is much more grim”) or in distaste for the lament of the put-upon white male artist (he cops to his self-deprecation being strategic).

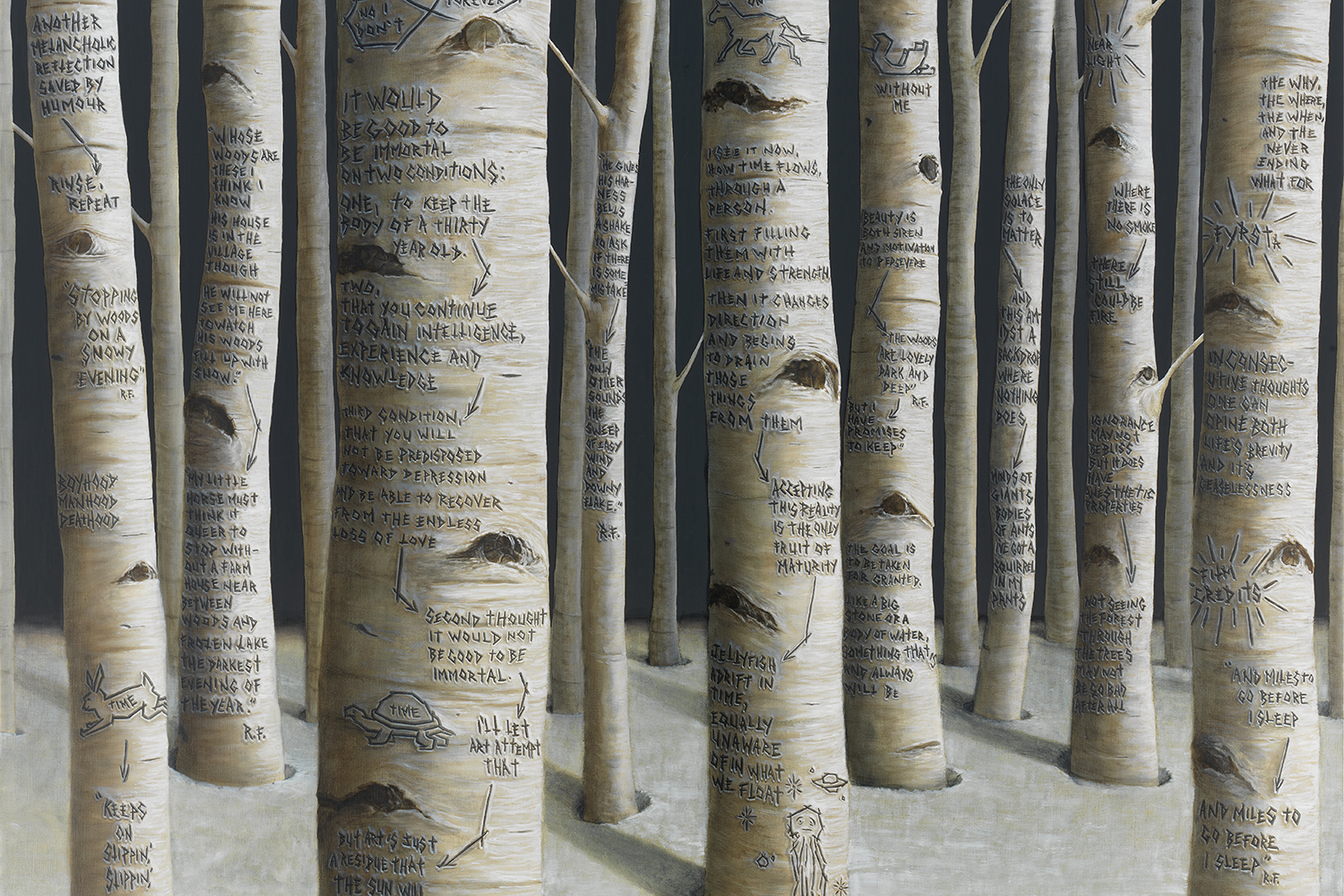

Landers often imposes a visually systematic way to express the tumult of his thinking. Canvases riddled with wooden signposts, the kind encountered on a hiking trail, fill the first two rooms. Yet, like some ontological Choose Your Own Adventure, these markers highlight directionlessness rather than direction. “I’m trying / to make life’s / inherent sadness funny / but it’s barely funny / in the end,” he muses across multiple signs in his 2019 work At Least We Have Wine. Elsewhere, grievances are featured on slender, knobby birch trees in eerie dark woods. Scarred with inscriptions, the trunks exhume Landers’s insecurities and posturing, like his inscribed ratio “80% dummy 20% genius” in the 2015 work Joke? Joke! Joke. Painted bibliothèques of ordered vertical and horizontal spines spell out his thoughts in lieu of titles. By contrast, his 1993 work Patches showcases his frenetic thinking in a more ambient, free-associative manner and on a bigger scale, using black text against a plain white backdrop (sprinkled with references to Olivia Newton John, Rudy Giuliani, and Eurydice). Without a systematic structure, the viewer’s eye scatters, though the work aptly reflects the inner tangle of levity and misery.

The exhibition concludes with Landers’s “Plankboy” series, an odd character with emoji-like expressions who emulates the gestures of Narcissus and Sisyphus. Here, Greek mythology speaks of misfortune in place of the artist. “Art is little solace,” he writes on a birch tree, “but it is solace.”