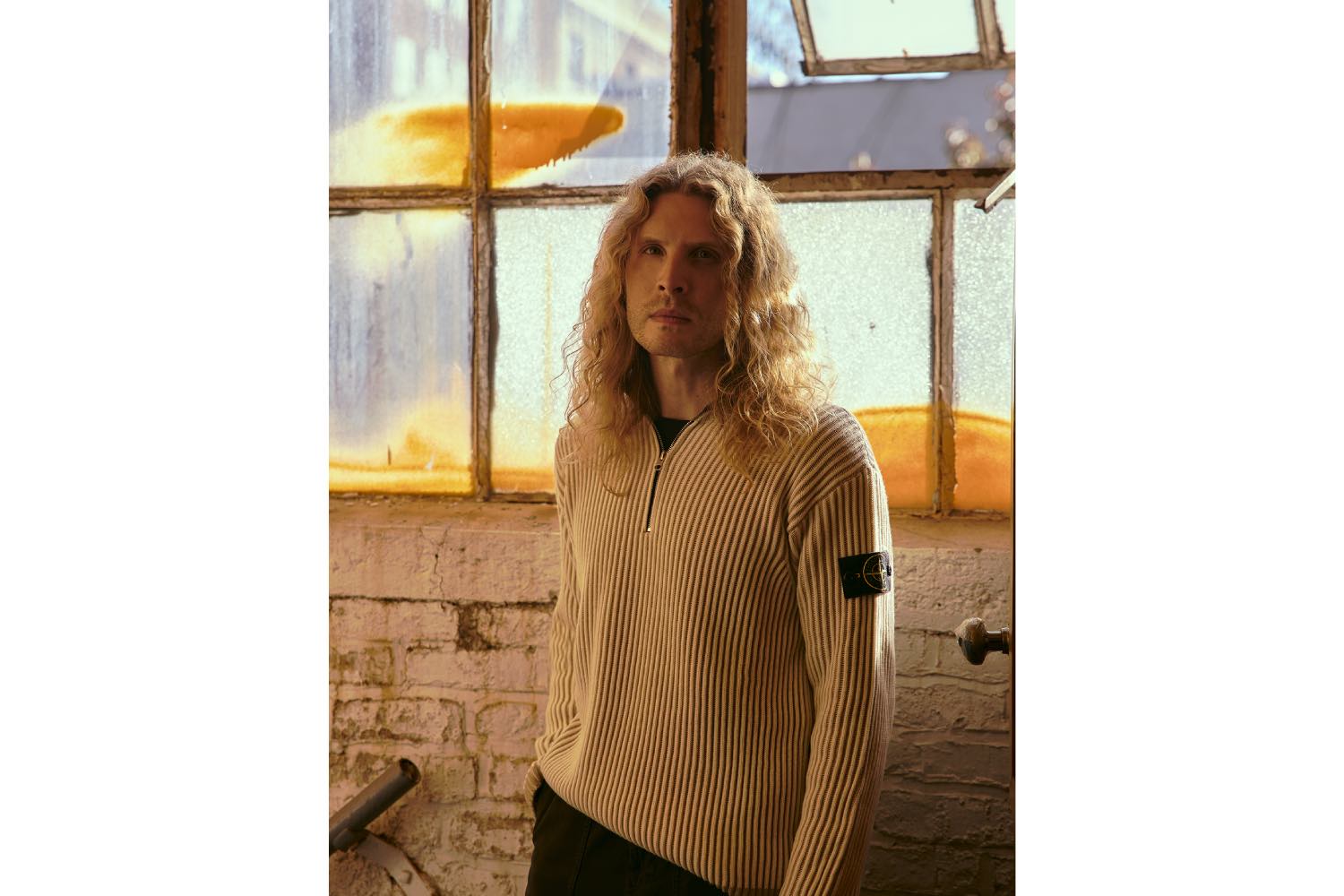

During an inspiring video conversation over coffee with New York City-based artist Brett Ginsburg – an evening decaf espresso for him, contrasting with my morning americano – we explored the nuances of his spatial choreography, the contemporary ebb and flow of meaning, and the art of manipulating the viewer’s perspective through a transformative experience that resonates beyond the typical white cube space. Entering Ginsburg’s American debut exhibition “Cadence” at Matthew Brown is akin to stepping into a meticulously crafted labyrinth. Ginsburg ingeniously transforms the gallery’s columns from mere structural supports into dynamic elements that facilitate visual fragmentation and synthesis. Compelled to navigate these architectural interventions, viewers find themselves experiencing a series of shifting viewpoints that challenge traditional perceptions of space and stability. Interlacing eight paintings with a selection of sculptures and experimental works on pressure distributive film, Ginsburg’s exhibition is a meditation on the interconnections between technology and biology, and the natural sequences and patterns that arise at the fringes of our reflexive experiences.

Cusson Cheng: I was thinking about your two most recent solo shows, “Cadence” at Matthew Brown in Los Angeles and “Wind, Water, Wood” at Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler in Berlin, as there are nuanced connections between the two projects. Can you tell me more about how you conceptualized the presentation for the Berlin exhibition?

Brett Ginsburg: In “Wind, Water, Wood,” various constellations took place in the space. Paintings functioned like visual terminals, and discrete sculptures on cables were suspended floor to ceiling across the entire footprint of the gallery. The exhibition consisted of multiple points, almost like propositions, through which a viewer could traverse or trace like an anti-narrative. Within these constellations, however, I found the negative space between each work as significant as the works per se. Perhaps it was because I have studied architectural drafting, CAD, and related software in my early development alongside making art that enabled me to be sensitive to spatiality.

CC: Are there any recurrent ideas you continue to explore and investigate in “Cadence,” and do you have an evolved approach toward these notions?

BG: There are different motivations between the two exhibitions, yet they are closely proximate to each other. In “Cadence,” the title refers to a musical rhythm but also conceives how the exhibition is a mode of action that lends itself to intuitive exploration through call and response. This exhibition also prompted a more of a planar approach to Matthew Brown’s existing architecture and axes. Initially, the irregularity of the space and its central structural columns posed a challenge in conceptualizing a coherent layout; because of this, any direct sightline across the space is obstructed. Looking back, it’s interesting to consider how the vertically strung cable works in “Wind, Water, Wood” interfered with the paintings I presented. That sense of obstruction I created in Berlin later manifested inherently within the architecture of the gallery in Los Angeles through its central structural columns.

For “Cadence,” I then began envisioning the columns as a device that could structurally support the exhibition and splice through the space in the form of a panorama. While this creates an emphasis on the horizontal axis, the vertical was acknowledged as where I began to see the sculptures indexing the negative space below and above the paintings.

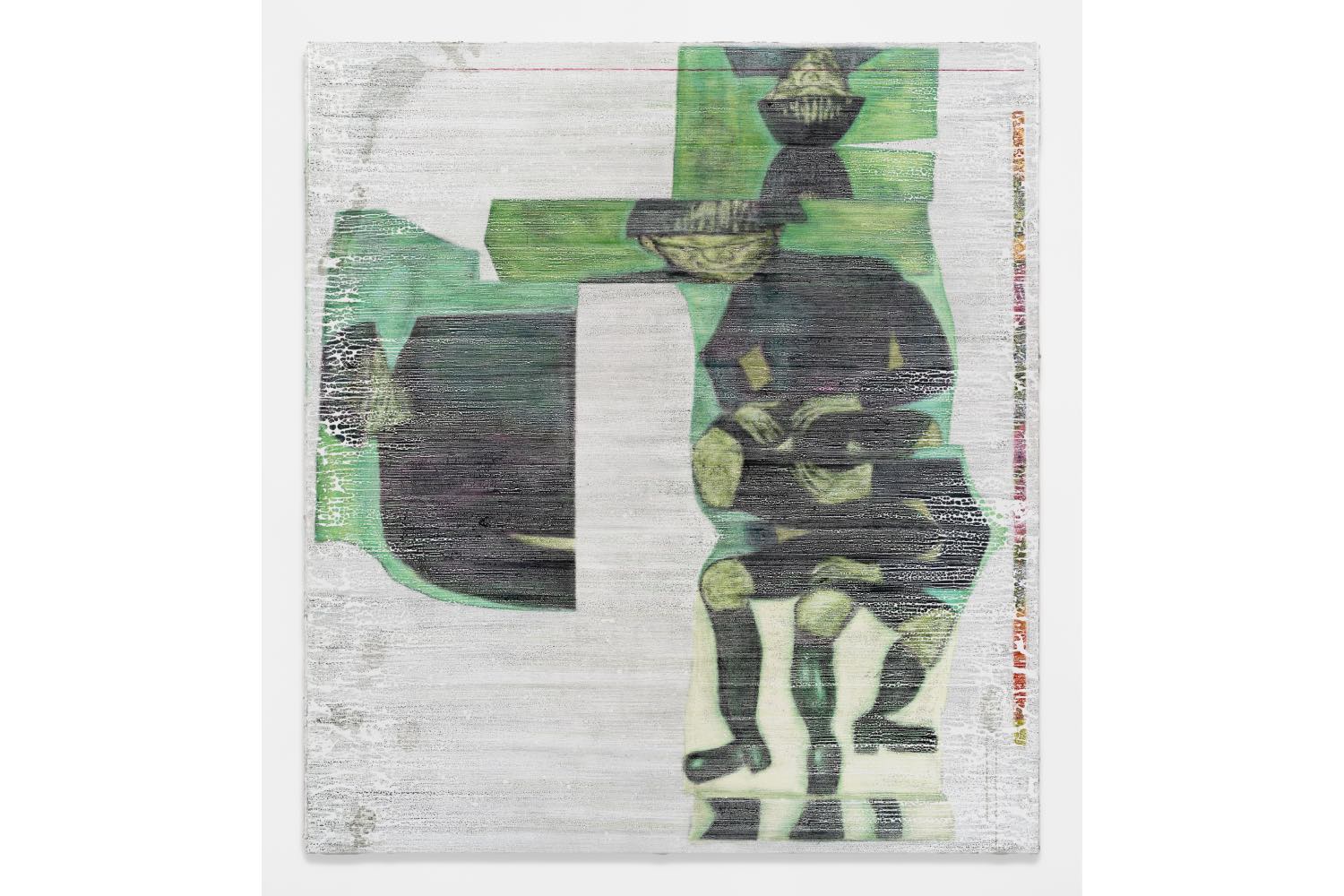

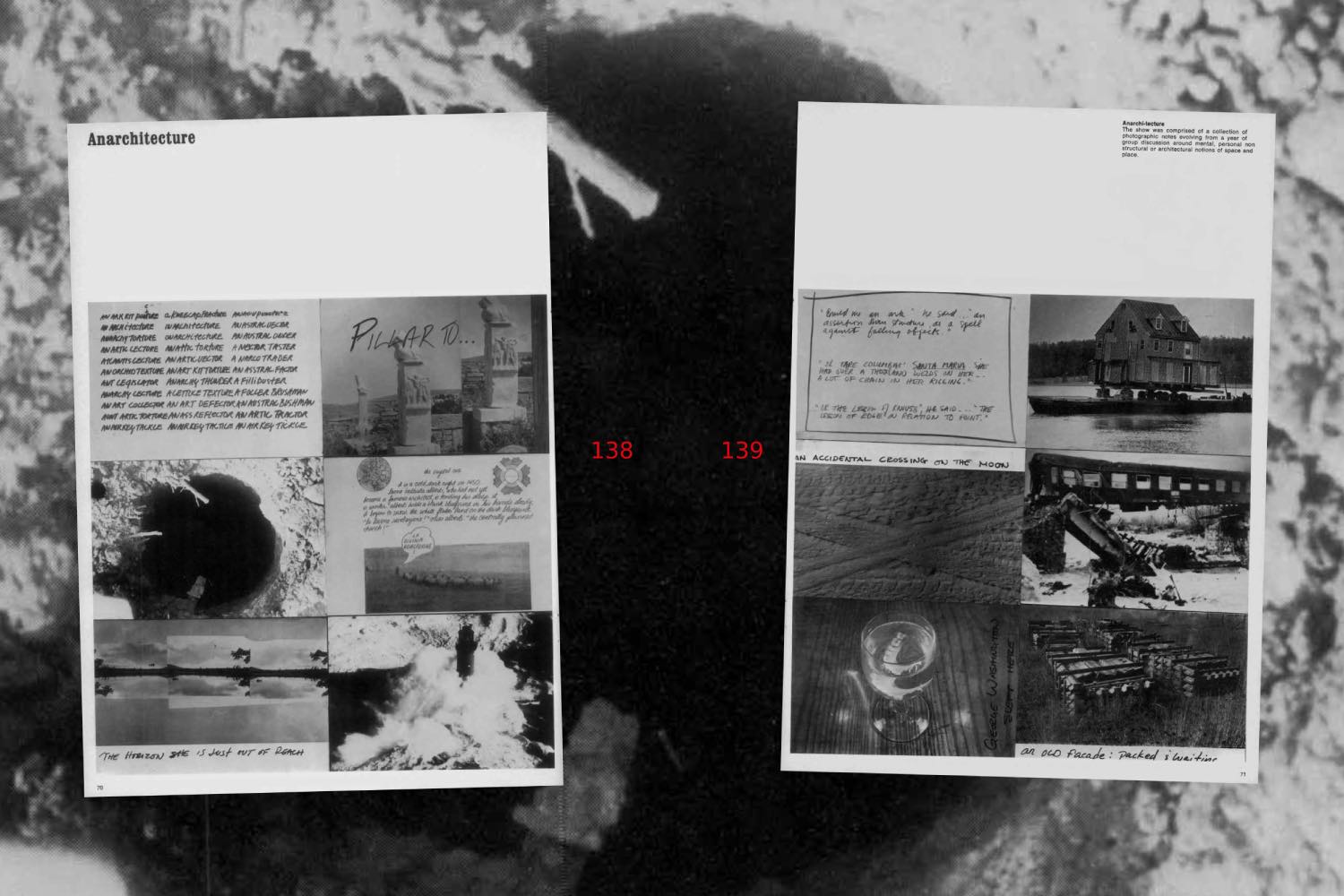

I also started to ponder the idea of the exquisite corpse (a method by which a collection of words or images is collectively assembled) as in how the exhibition itself can be cut up and scattered by the inherent divisions within the space, where the viewer is prompted to experience the exhibition as if they are navigating an exploded architectural drawing by moving through it. These visual clippings inspired the idea of cropping or eliminating information pictorially — there are context clues, yet nothing is resolute. I am always thinking about how much of a subject need to be revealed.

CC: When I saw your paintings in Berlin, I was captivated by their unique and compelling aesthetic. How did you discover the various techniques to create such intriguing works?

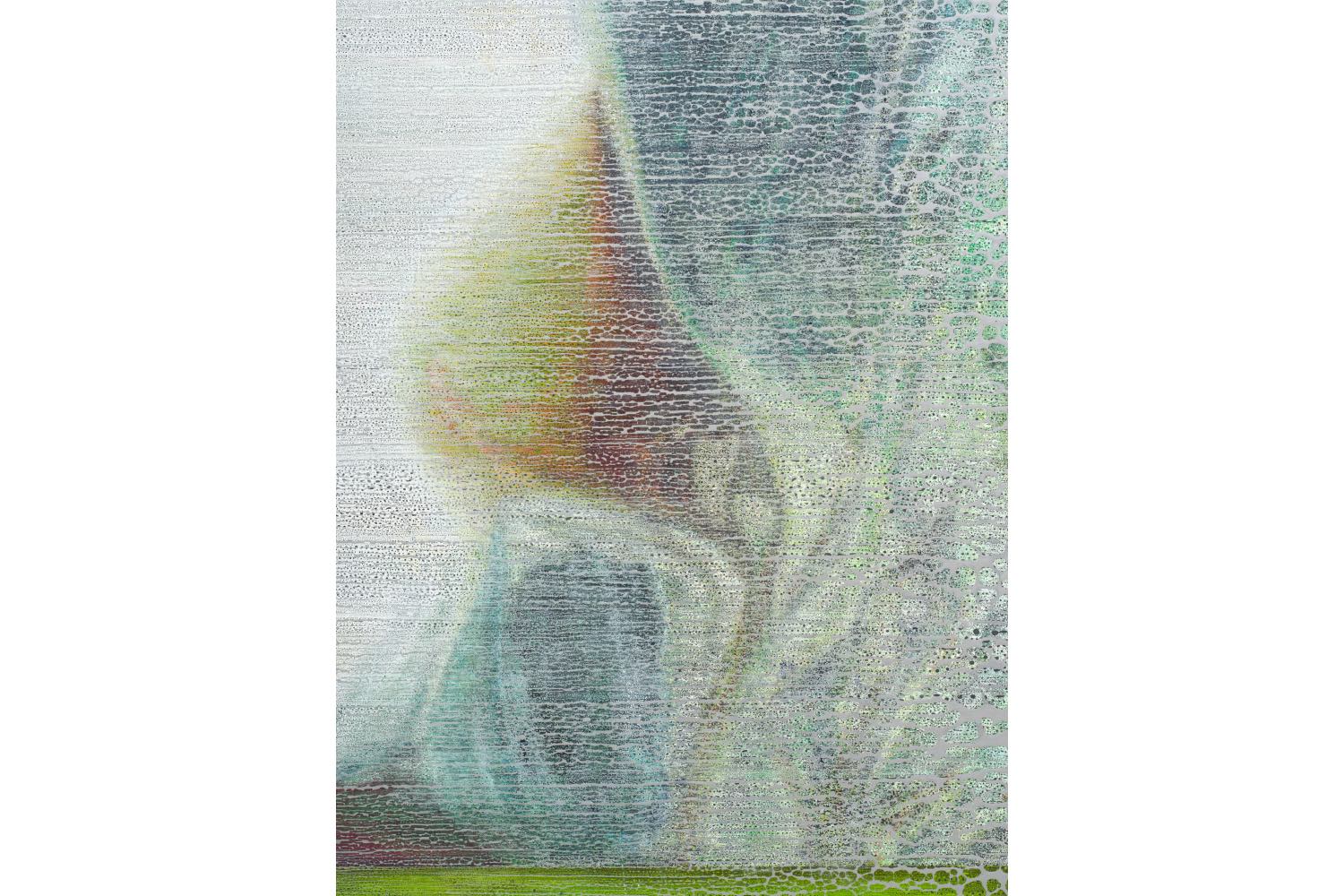

BG: When I paint, I think a lot about the notion of translation, especially what gets gained and lost. I perceive my creative process as almost akin to abstraction, and it is proximity to mold-making and monoprinting. It emerged from various permutations and translations of processes I explored while originally working with ceramics; painting into plaster molds that would get rehydrated and absorbed through slip-cast clay. I was struck by ceramic casting and how it merged the presence, absence, and spatial capture of mold-making with the indexicality of printmaking. As my practice shifted away from ceramics and the dependency on those facilities, it has taken on many different iterations; years ago, I was painting directly into the bed of my truck in Los Angeles and peeling forms out.

CC: What is your current creative process after years of experimentation and development?

BG: The recent state of my process occurs against plexiglass. Although the surfaces of the paintings are confusing to reverse engineer, procedurally and pictorially, they happen entirely by hand with paint and brushes. The first layer you see is what goes down first. Every granular unit of color is a layer that becomes homogenized with each subsequent layer preceding it on the glass plate. My process itself is durational and continuous, and then, when the paint membrane is extracted from the plexiglass, it appears almost alien divorced from its forming device. When we typically see paintings, there’s a relatability to the brushstroke. However, for my work, the paint is applied against a non-porous surface, so it retracts on itself. They’re materially incompatible, which excites me because I ponder how can this resistant mark become the dominant singular mode that comprises the entirety of the image. Morris Louis once said, “It’s not a question of what to paint but how to paint.” Even though I have been exploring my relationship with imagery lately, this question still interests me conceptually regarding his approach with diluted paint and how he would manage its flow dynamics to interrogate the picture plane.

CC: I love how you have this quantum way of understanding materials and playing with the different potentialities of forms and images. “Cadence” is like a quantum space for the viewers to unearth how you dissect, deconstruct, and rebuild spaces through paintings and sculptures. The exhibition title also made me imagine how you employ sound or invisible energies to materialize and dissipate different forms of matter.

BG: I’m interested in how everything begins with a firsthand experience, encounter, or reflection, especially their vibrational qualities, and slippages within a built environment or site. I am fascinated by how everything exists contingent upon one’s familiarity with a subject or an abstraction, and through the interdependence and interrelation to other matters.

CC:I also noticed that you included some intriguing sculptural works in the presentation in addition to the paintings. How do these pieces expand from your pictorial experiments and further inform the themes you touch upon?

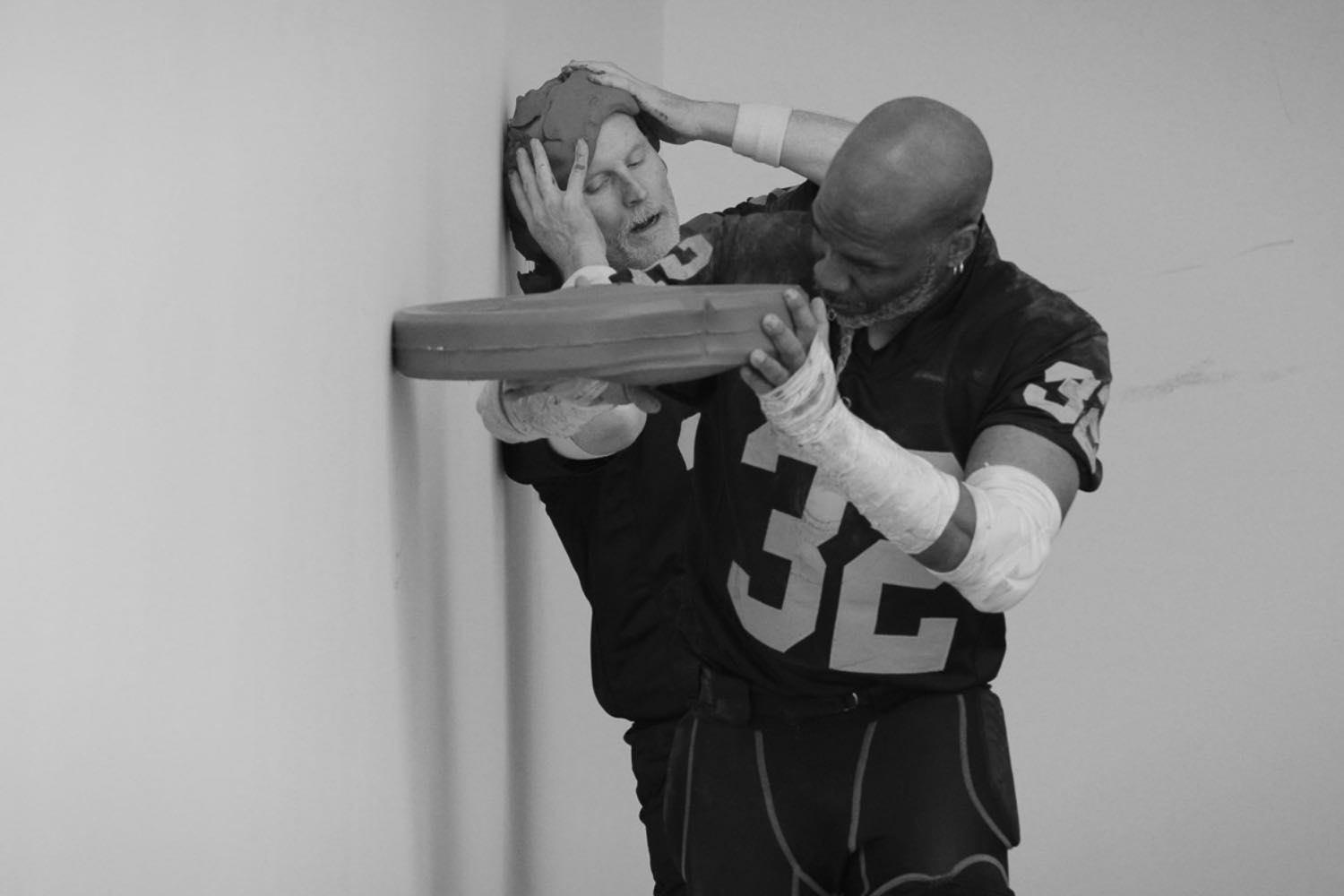

BG: I perceive sculpture as a way to understand and distill form while also considering material metaphors. If my paintings can capture an apparatus or viewpoint, then the sculptures allow me to isolate and manipulate components within space and reciprocate visual encounters I have had myself with a viewer. I feel most excited when I can push existing forms into an indefinable space, where parts function through adjectives rather than identification and oscillate within a new context.

For instance, the work Temperate Bounds; Prounenraum Margins (2024) in the exhibition houses thermo-bulbs suspended along the wall. The bracketed work encapsulates the bulbs latency but also how I felt surveilled by them as they lined the perimeter of a spray booth I once worked in. I later realized they were monitoring the space in the most analog way. If the space exceeds a certain heat level, the temperature-rated fluid within the bulbs may explode and drop an alarm line that they are tethered to. These bulbs are commonly installed in spaces where particulates constantly interact with the atmosphere in ways that a typical fire detector cannot comply with. My iteration aims to relocate the architectural fixture within a new format and rearticulate their foreboding potential.

Just to share another anecdote: the floor-based sculptures in “Wind, Water, Wood” and “Cadence” are iterative of one another. The work Receiver (2024) in Los Angeles is designed to index the negative volume and footprint, featuring forms reminiscent of a packing insert or core mold for the casts oriented in the sculpture In Fluid Terms (2023) shown in Berlin.

CC:From lining up four canvases on each side of the column to form two seamless panoramas as the center of the gallery, to setting up various industrial sculptural interventions at specific locales, I notice that you have a distinct approach to installing the works in the exhibition. Do you have a specific way that you wish the audience to engage with your works in a slightly different spatial design?

BG: I consider the gallery space like a mold or forming device, an apparatus for containment and material. I then explore the possibilities of drawing materially in space. The panorama is immersive in the way that it renders a spectral presentation, both formally and conceptually, creating a space of its own. This format allowed me to contend with a montage-like approach where unexpected parts could press up against one another pictorially. Viewers are compelled to perceive the painting sequence almost as if they are a scanner themselves; laterally moving across the surface to process information. This motion reminds me of my time living in Los Angeles, and when you’re traversing the city there is this acute awareness of the slow, lateral sprawl.

CC:What I admire about your approach is how you encourage the viewer to engage and create their own connections to the space. Some artists adopt a very linear approach in exhibition making, where it only makes sense if the viewer walks through the show clockwise, or you can just quickly figure out the logic behind the setup. For you, however, it is much more nuanced and fragmented, I might even say more playful as well, especially seeing how you decide to build a painting panorama in the gallery space. I enjoy how you exhaust every possibility of the site and attempt to come up with a design that is condensed yet simultaneously scattered.

BG: Yes, I would say that’s a great takeaway! For myself, I wanted to slow down the entry and viewing experience. I had the windows filmed, so there were no preconceptions from the outside. Entering the gallery space becomes an act of unfolding. You walk in and first encounter a cast resembling a piston. Then there’s the panorama; as you move around it, forms containing the negative relief of the entryway cast emerge as sculptures anchoring the corners of the gallery. I just wanted to set up a condition where one has to move through space to stitch the entire thing into a singular entity. Each component is nearly viewed in isolation yet tangential to one another. I hope the exhibition can hold a mirror to the hybridity of our surroundings. Viewers may ponder what sorts of structures or ecosystems are alienated or visually subverted but allow societies and environments to function discreetly. How can one comprehend a subject not only by posing questions, but through various material translations? Furthermore, how are our surroundings functioning through various state changes or their molecular makeup, and what are they made to withstand?