My first introduction to Berenice Olmedo’s work, which encompasses sculpture, performance, and installation, was a photo of the artist dressed head to toe in a leather-and-fur outfit. At first I assumed it was some kind of art-as-fashion statement, and then I saw the mask-styled hood she wore, slyly draped over the top of her head. Resembling a cross between a German shepherd and a coyote, its gnarled snout, pointed ears, and glaring eye sockets imbued the sartorial splendor of its constituent parts with an abject ceremonious quality. When I read that the provocative work, part of a larger series, “The Bio-Unlawfulness of Being: Stray Dogs” (2012–15), made while Olmedo was an undergraduate, was created from the carcasses of run-over dogs collected along Mexican highways, I was instantly intrigued.

Many young artists have ruined their careers making art out of animals, an inevitably risky pursuit. Tom Otterness took a dog from a local shelter, tied it to a tree, and shot it to death while filming the gruesome act (Shot Dog Film, 1977). Only twenty-five years old at the time, he never quite recovered from the stain of his extreme gesture. Thirty years later, Guillermo Vargas infamously tied up a stray dog in a Nicaraguan gallery, prompting more than a million people to sign a petition in protest. Vargas claimed to have cultivated this outrage to reveal the hypocrisy of white Western privilege. To be so disturbed by the spectacle of a single street dog and yet unbothered by the reality of their vast numbers throughout the world, or the systemic conditions that beget such suffering, was the real injustice, he argued. Few were swayed.

For Olmedo, the plight of the stray dog, a familiar presence in her native Mexico, lies in the creature’s paradoxical legal status as both dangerous fauna (a disease-ridden threat) and possession (an object without rights). Embodied respectively by the notion of roadkill and that of “pet” in human society, this status, for the artist, encapsulates an anthropocentric orientation to the natural world that is narcissistic, exploitive, and deeply irrational. Dogs are said to be man’s best friend, to serve us with unparalleled loyalty, to even resemble their owners (as Olmedo’s canine costume wryly evoked). Yet cows, chickens, rats, etc. — routinely tortured for our benefit by the animal and medical industries — are not. Olmedo locates the biopolitics of such unequal relations in capitalist notions of security, health, and efficiency, which her work with stray dogs brilliantly entangles. Consider the soap she produced from their fat, which she sold in a Mexico City flea market known for trafficking in illegal goods, including dogs and puppies. By alchemically transforming something deemed pathological and dirty into an emblem of hygiene, and placing it in an economy similarly seen as contaminated by poverty, illness, and criminality, she underscores stereotypes of the Global South that regard it as unclean.

Bodies that do not serve the capitalist machine have long been coded as diseased, in need of correction, seclusion, or annihilation in order to maintain societal health. Rooted in heterosexist, white supremacist, and ableist standards of normativity, the administration of such bodies inevitably links animality to disability. As crip scholar and vegan Sunaura Taylor persuasively argued in her 2013 essay “Vegans, Freaks, and Animals: Towards a New Table Fellowship”:

We understand animals as inferior and not valuable for many of the same reasons disabled people are viewed these ways — they are seen as incapable, as lacking, and as different. Animals are clearly affected by the privileging of the able-bodied human ideal, which is constantly put up as the standard against which they are judged, justifying the cruelty we so often inflict on them. The abled body that ableism perpetuates and privileges is always not only nondisabled but also nonanimal.1

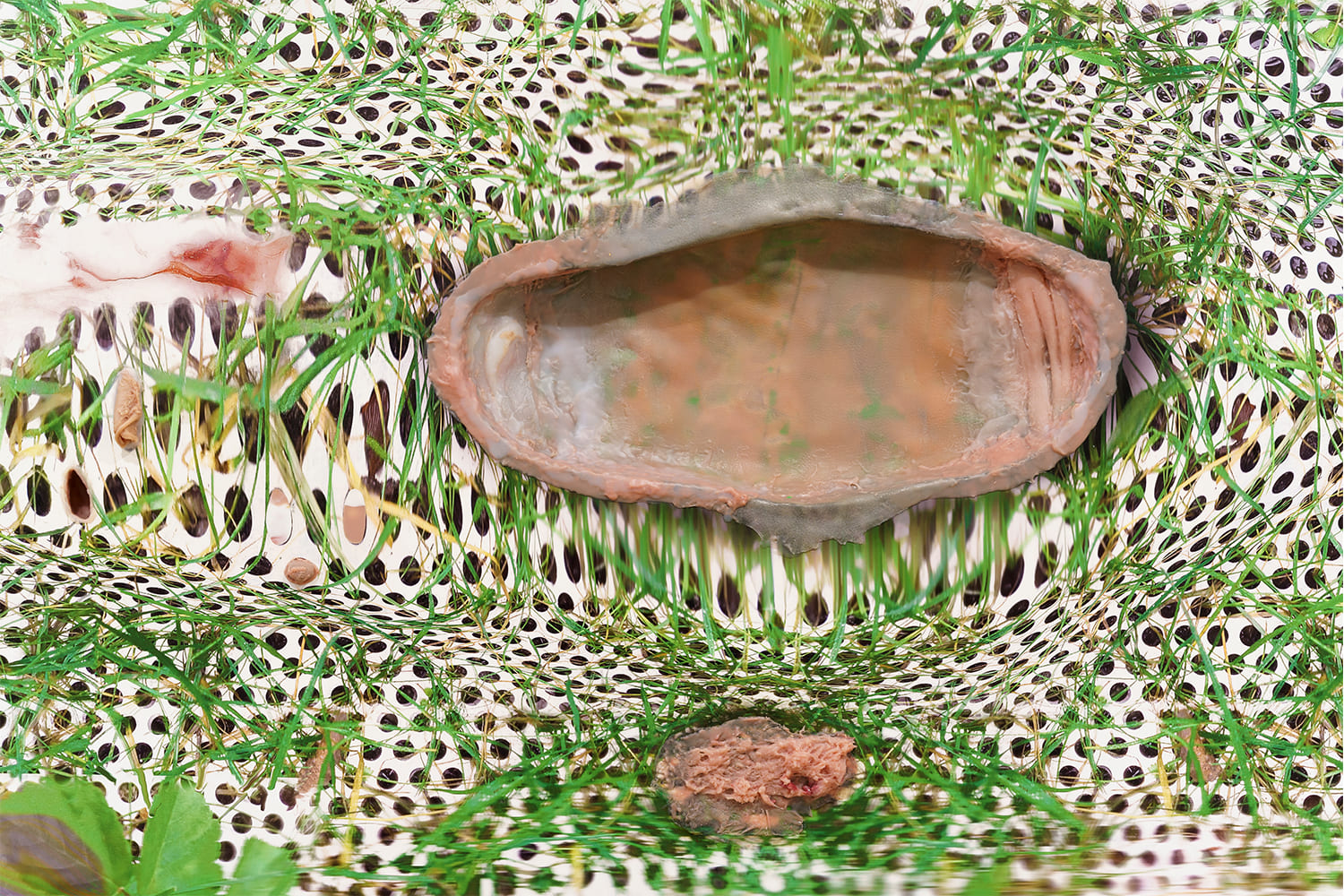

Taylor’s views are instrumental to understanding Olmedo’s recent work with children’s prosthetics and orthotics, collectively titled “Anthroprosthetic” (2018– present). Such devices, created to replace missing body parts, or assist what is perceived as broken or malfunctioning, are repurposed by the artist to challenge ableist notions of use and deformity that deem certain bodies — the very ones for which these objects were made — inadequate and in need of improvement. Assembled from discarded or obsolete devices acquired by the artist in the same flea markets mentioned above, or directly from their former owners, they echo her work with dead animals (Olmedo works with rats as well) as she similarly recuperates, repairs, and revives their debased forms.

The most haunting works in the series are mechatronic, spectral figures literally choreographed to fail. Unable or unwilling to conform to normative categories of health that privilege the upright, independent, and human, they confront us with the oppressive limitations of ableist views. Often this is framed by their fragmentation and horizontal predicament. Embedded in walls and pillars, the truncated legs in her recent exhibition “Eccéite” (Cologne, 2021), for example, slowly raise and drop their knees to no avail. In áskesis (2019), a trio of pressure mattresses — designed to promote blood flow in bed-bound patients — that have been corseted with back braces inflate and deflate with the same futility, their slumped forms appearing exhausted by the effort.

Olmedo frequently titles her anthropomorphic assemblages after the pediatric patients whose prosthetics she appropriates, including those she knew while volunteering at Mexico City’s Centro de Rehabilitación Infantil Teletón (CRIT). Valentina (2021) consists of a little girl’s pair of black Mary Janes that have been awkwardly “fitted” on the outside edges of bent metal poles that extend like legs to meet a tiny leather girdle. The shoes, with their faded pink flowers painted on the toes, and the worn glitter tape still visible around the poles, imbue these clinical artifacts with the corporeal aura of a childhood most of us would pity. Like the nearly invisible strings that twist its little girdle-head to and fro in a funeral pace that will never allow the body below to fully right itself, the ghost of Valentina’s past warns us that the myth of autonomy is a trap.

What disables us is a society that refuses to embrace our interdependency, that does not recognize the wellness of diverse bodies, that fears the underlying vulnerability that conditions all life. When I saw this awkward spindly persona at Interstate Projects, New York, lying on its side among other Olmedo sculptures scattered across the gallery’s concrete floor, its eerie spot-lit form delivered this message with a tender fortitude.

All of Olmedo’s work is marked by an eschewal of polemics and a resistance to binaries — wellness and sickness, human and animal, flesh and machine — that limit our understanding of bodies and their full expression. To that end, her latest assemblages (Hic et Nunc, 2022), combining transparent Durrplex with silicone liners (an internal coating for prostheses), once again defy classification. Suspended from the ceiling like an ad hoc school of industrial jellyfish, their vertical bodies move up and down, simultaneously clear and illegible, phallic and curvaceous.

When I ask Olmedo what it means to make this work as an able-bodied human, she poignantly explains: “It would seem easy and not so risky to question disability from the comfort of a body with no motor limitations, amputations, or congenital anomalies, yet disability is not limited to the phenomena occurring in the body; disability is political.” In fact, human beings are perpetually disabled by the social and linguistic machinations of capitalism just as animals are.

The question is, what are we going to do about it? Olmedo’s practice suggests we must first separate the value of a life from its so-called productivity, and free all bodies from ableist notions of inferiority that naturalize oppression.