Andrea Lissoni: Let’s start from your new commission for Tai Kwun Contemporary in Hong Kong, “One Hundred Nine Minus” 一 百零久减 (2021), which opened in May. You will do a performance at the end of the exhibition. Will you be rehearsing in the actual space?

Pan Daijing: The sound installation is already on since the beginning of May. The finale — let’s say the actual body of work — is going to happen around mid-December, for twenty days. The first stage of development and engagement with performers is centered around filming. So each individual in the cast is being captured from audition to rehearsal to the actual exhibition. So it will be a lot about the performer’s space — not just the space I create for them. And I will be rehearsing during this time, we’ll be partially in the former prison and police station where the art center is located, partially in various locations, some of which are private, personally related to the performers.

AL: There’s a feedback between the filming and performance processes, amplifying both creative outcomes. Meanwhile the sound installation is going on. Will audiences still be visiting during the installation? Is the sound they are listening to now in the three floors of the tower the same sound that will be there in December, or will it be completely different?

PD: Yes, they’re hearing it. The moment they enter the space, three floors in total, they will hear it. As they’re climbing up, the sound becomes more and more evident. But it’s not a work that is made to make you aware there’s a sound installation. It’s very different. It’s more like an environment, but people will hear the calling. Right now the sound piece is part of the group exhibition that’s on view. In December I’ll take over whole space to present a larger piece where this sound installation will be part as well. So the work grows basically over half a year’s time and expands into something that occupies the entire floor and forms a performative environment.

AL: I appreciate that you’re defining the work “an environment”. Yet, there will be performances, and where are the videos appearing?

PD: Let me try to clarify: there are three parts to the piece – a sound installation on the spiral staircase as you ascend, then a dark room where video is shown alongside an installation, forming a reality that is very personal to the work and the performers. The third part is a bigger, fictional space you enter through a tunnel, an environment built for its audience to inhabit, where the performance will take place. There will be a performance every day for eight hours. I’m thinking to imagine it as a journey. It starts with sound: you’ll start from the ground floor, then you’ll walk up the stairs. You hear the calling, and then you enter these two rooms, a bigger one and a smaller one. In the latter, all the walls are black. I call it the “night room,” which will be focused on the videos. Then you walk into the “day room,” with a white wall that is filled with natural light. And I’m thinking of turning it into a completely different kind of environment that doesn’t feel like a gallery or anything. It will evolve each day. And during this period, the environment and all the installation will also slowly be being modified. The performance will feed the environment.

AL: This whole process of apparition, growth and transformation is both fascinating and inventive. However, there isn’t so much that can be shown yet. There are no images available. So perhaps the question is where does the music come from? Did you create it from scratch or was it something you already had and morphed into the process of transformation?

PD: From scratch. The compositional approach this time had much more of a human touch. I wanted to really explore the philosophy of improvisation. Before, the music was always, in a way, very confrontational. Not the style of it, but the way your ears confront the music. This time, I felt like I wanted the sound to be like a lighthouse. We were talking about this “environment”: I feel like in this world I’m building there is always a beacon. The work can be very dark, but there’s always a very bright light. I want this light to be this sonic vision that I have, that will grow, and the further the work develops, the brighter the light can be, until it feels like it’s light exploded. This source of light grabs you and pulls you in. Instead of the listener facing and confronting this piece of music, I want a feeling or understanding to be generated through sound. I want it to be contagious. Because I have time now — I have different phases to be able to develop work in a different way. So I want to test out many, many ideas and build it from scratch. Still, I am in the role of a composer, but as I was writing I didn’t look at this piece of music as a piece of music. It’s a very different approach.

AL: Let it put this way: if the music was coming from something that I am familiar with, where was it coming from?

PD: Well, the familiarity comes from the texture, because the sound installation is still based on the voice of two opera singers. The countertenor’s voice is like an instrument. So the countertenor is still a countertenor, the soprano is still a soprano, but we are doing a very different way of recording. My writing methods have completely shifted in this piece. This time I’m letting the voices mutate into each other, focusing on the interaction of these voices and experiment with storytelling. I’m running a lot of the vocals through analog machinery – not to add effects, but just to process the texture. It changes the spatial relationship between the voices.

AL: You do this on your own? I mean, with your instruments and your gear? Don’t need a studio?

PD: I have a studio set up that grants me a safe space to create, where I do most of my research, writing and recordings. The recording process is a performance itself. I call them sessions, almost like doing studies in the moment. And I take elements of those moments and put them into one piece.

AL: I want to go back to the image of the lighthouse. There is always a dialogue with verticality in your work, be it a tower, be it ropes hanging from the ceiling, be it light hitting the public from above. However there’s something in the lighthouse figure you employ that I think we can discuss, which is: the light is there, but it’s also sort of not always there. It’s rotating, it’s pacing, it is giving a rhythm, as a beat. It interrupts, it is in and out, in and out, off and on. You know what I mean?

PD: It’s good you mentioned this because it’s very important. We were talking about life, and the opposite is death — but it’s not still. Something can be still, but can still be alive. So I feel like it’s very important that this thing is ever-changing, ever evolving. It doesn’t stop. It kind of doesn’t give you a beginning or an end. We’ve spoken a lot in the past about the idea that our sense of time can be distorted through sound. It’s important to me that my audience feels that. That’s the beauty of “liveness” for me. It draws focus to the present moment. This is particularly true of live improvisation – a decision is made at the beginning and then you just let go, it’s almost like a stage dive, you know? I feel like when something is constantly evolving, you can’t really grasp it in a way. The feeling of lighthouse: it’s not a light bulb. It’s not something steady. It’s a guide. When you see something at the end of a tunnel, sometimes you’re not even sure if you actually see it or if it’s a hallucination. It’s an idea, a hope. It’s a fictionalized reality. I think that’s very important. We’re talking about fiction not as a story or something, but more like how much you trust your mind, how much you trust your vision. And in this work I also want to bring up the question of how much we can trust our ears, and what that does to us. I feel like, in a way, the lighthouse is a visual thing, you see the light, but it can also be just in your mind.

AL: All this resonates with something I’m familiar with, either I saw a piece of yours or I’m familiar with the venue and I can guess… But talking about Done Duet – 重奏 (2021), your commission for the 13th Shanghai Biennale, I have no real clue. So perhaps we could begin by simply describe how it looks. I’m aware there are many stages of images, but I also know that you’re extremely accurate in choosing images. On your website there are four main images: one features ropes hanging from the ceiling. It’s steel — they look like fiber, but it’s steel. And the end is quite uncanny: why did you want the steel to end in an hook?

PD: It has the possibility of extending — and you can hook something onto it — and it’s also something that reminds you of when you’re hanging something up, you always have another thing. It has the possibility of connecting with something, and this something can be functional, can be a dead body — it’s up to you how you want it to be. But I think many people, when they see this, probably recall a feeling of death a little bit. I had the steel treated with a strong acid so it would constantly interact with the air and change the whole time. Every day the color is a little bit different. And in the middle, you see, there is a very long string of hair — it hides among the steel. In the images, you can barely see it’s hair, but in real life you can see it, and from the hair there is water dripping every thirteen seconds onto this plate. And because of the acid, it’s getting more and more rotten every day, so the water is changing color. Obviously, because it’s quite dark, from day to day it’s hard to see the change. The color changes — it interacts with the humidity and the air.

AL: On the floor there was a white material, like sand. What is it?

PD: It’s quartz, a kind of a crystal stone. It’s just industrial material. They use it for building and industrial use, and there are different sizes so we just chose the size and the kind that’s closest to the feeling of salt.

AL: So, the quartz defines a sort of field in which there were some white bags. And on that field there is a performance, right?

PD: Yeah. That was only on the opening day. Actually, the performance, from my perspective… It was more of an introduction to how this environment can be interacted with. Like an invitation — I consider it more like an invitation. I wanted the audience to understand, which, luckily, happened that way: there were many people sitting there, lying there, playing there, just interacting. They were actually inhabiting the space. So the performance was for them to use their body to inhabit the space. Because I feel like this environment needs to be cracked open. It’s finished — the making of it is finished. And then when it opens, a new chapter starts. So the performance was kind of like an activation. It cracks it open. Now it’s dirty, now it’s started. After the first step, stepping on the quartz, it’s never fresh anymore.

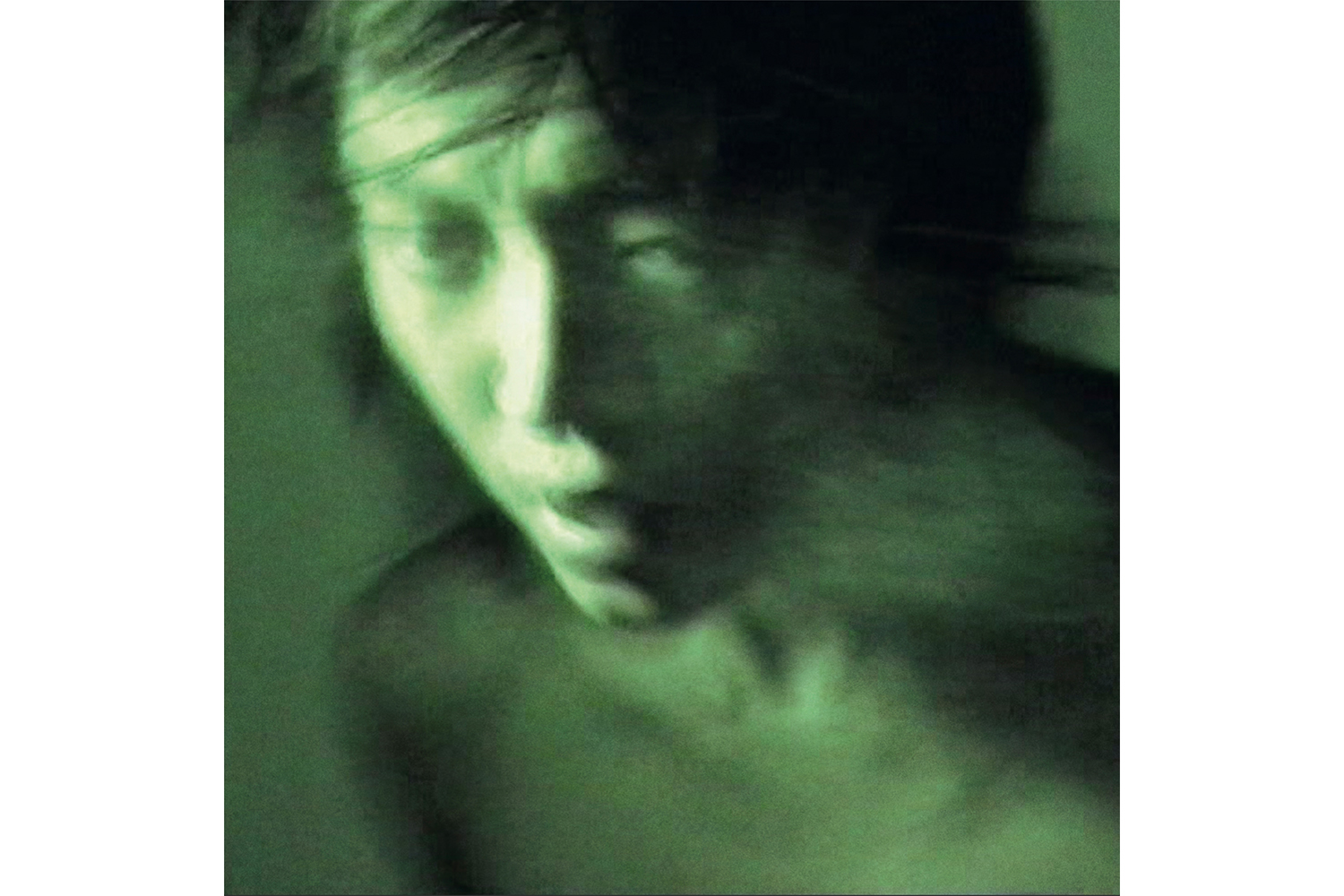

AL: I understand it as an invitation, as you call it, but you also generate a sort of bodily tutorial, am I right? I’m sure they will leave traces on the quartz. You seem to be working with a ghost — the ghost of the possibility of going there and crowding and slipping and lying and perhaps just spending time, hence suspending time, which is quite mesmerizing. Moving to the following image: what a surprise, a body in a storm, apparently striving in a foggy snowstorm? This says something about the feeling you want to share with the audience.

PD: Actually, I shot that footage outside of my window in Berlin. That was the beginning of this piece. It was a father pushing his kid on a sled. It’s almost dark, one of the heaviest snowy days, but the kid wants to go play. The father took him. I was there watching them for two hours. He was just pushing him, pushing him, and he was so tired. He’d kneel on the ground and he’d push him. I thought it was so beautiful. I just recorded five minutes when he was exhausted, kneeling down on the ground and pushing him. It happened in front of my house. So I just took that screenshot as the inspiration for this piece.

AL: It suggests the feeling of snow, water and life. It’s very much there. What is the sound in the piece instead, and where does it come from?

PD: If I could describe sounds I’d be writing about them, not making them. But to answer your question, the composition is a duet for one countertenor one soprano. That’s partially why the piece is called Done Duet. They are singing the whole time together, and it is just the voice. The whole piece is thirty minutes purely made of voice. You can hear their voice, their breathing. Unfortunately, usually with sound, it’s very difficult when you cannot visit. I couldn’t go there during the development phase because of the pandemic, so I could only imagine. The idea is to create this illusion that the voice is coming from above, kind of washing down. Lighting plays an important role in my work. For this piece, I’m working only with natural light and its reflection with water, and other material we use. It looks quite dark compared to the other works, but still there was a lot of natural light. But I wanted people to be lured in because they hear this sound. And then when they walk in, they forget they’re seeing or they’re watching. They just feel they are in a different world and there everything is together — a sense of belonging. This is what I was aiming at.

AL: What I understand is that the subtle feeling of a liquid dropping from above is echoed by the sound, similarly coming from above. And at the same time, the two spaces are somehow loosely in dialogue with the duet? This seems to be the DNA of the work…

PD: At the very beginning the compositional concept was the idea of spinal fluid. I was viewing these two spaces as the spine of the building. I have this personal history of my fluid in my spine being taken out when I was a kid, to get tested because I was very ill. And I remember exactly how that felt. It’s the first time I could sense the fluidity of my body — the core of my body, the spinal fluid. I mean, obviously it’s an illusion. But when they’re taking it out, you feel this very strong sense of what’s going through your spine. So I wanted to kind of transmit that feeling. Also, at the top, it’s just glass with daylight coming through. The voices are very gentle, there’s nothing “epic” about them. The only thing that sounds big is the reverb – the building itself. I wanted to use voices to “sound” the building, so that the building seems to be alive. I want the building’s soul to lie in the spine, like spinal fluid. I mean, it’s a similar approach to what I wanted to do at the Tanks. I didn’t want to do a light show. I wanted to utilize the lights to make it feel like the building, the spaces, were like a sleeping monster that is moving. So in a way that’s more about the building than about hearing the sound and having an image. But I do call it a vocal waterfall. It’s a sense of this liquid pouring down, but not a powerful force. More of a gluey thing, like a liquid that’s thick.

AL: And this is why the definition of environment is so poignant. There are edges, yet something spills everywhere, despite a sort of container, be it a ceiling, a wall, a body, an expanded body that makes that movement become perceivable. It’s inhabited by that movement and it’s the skeleton of that very same movement as well. You’re talking about composing, did you have a score?

PD: I always have a score. But of course it’s very different than Tissues I: A Prologue (2018), which we presented at the Biennale of Moving Images, Geneva, and Tissues at Tate Modern in 2019. Tissues is completely specific; the singers were given my finished composition and sing note by note as in classical music. Here I’m applying the way I work with dancers to singers: I give them a libretto, a line of melody, a sound, a gesture. So I become a lead. I personally feel it’s like directing actors. You cannot control their face or their body, but, without you being there, they cannot just perform out of the blue in front of the camera. So I’m giving them instant direction, constantly, with a script. The script is very abstract, obviously, or you can also call it a score, often with open structure.

AL: What seems to me quite relevant in the piece is that transmission emerges as a major preoccupation. All the details you’re describing – from what was transmitted through the feeling you had from your body a long time ago, to the way you ask the performance to inhabit the space, to generate a form that I call a “template”, a bodily tutorial – do refer to a system of transmission. And even the way you’re telling me now how you made the duet happen, it’s really based on this soft apparatus of transmission. You generate something and they take it from there: it’s inherently about transmitting — not being a moment, here and now — but being a fluid, an event stretching over time. From the generation of the piece, to the piece inhabiting the architecture, to the piece going in a very fluid fashion toward the audience that eventually inherits and shares this transmission.

PD: This sense of transmission has become my writing method, basically. Whether composing or choreographing or directing. I’m not giving them instructions in the traditional way; I’m always performing with them. But I call this “conducting.” My performance is conducting, my voice is conducting. I give them a frame, but then I don’t tell them exactly what to do. I use myself as the baton to conduct them. And that’s why it’s very personal, my relationship with the performers. In this piece my behavior, or my action and my performance, has a very intimate and strong relationship with what they do. I feel this in every work I do, no matter how much I am present. They are transmissions or extensions of this vision that I’ve communicated through my performance.

AL: You defined inventive ways to document every piece. Can Done Duet be documented, or do you rather recommend not documenting it?

PD: I documented it already, documenting has always been an important part of my work and also something I want to challenge. I actually made a short film inside of the work. It was kind of like research for this work I wanted to do for Hong Kong, because always in my performance I was focusing on the live, right? I never had the chance to just use it, to just be the person looking at the monitor. But this time I had the chance, even if it was very short, just two hours. I could direct the performers, do something not for the audience but for the camera. And we also documented the performance itself and the rehearsals, just as I always do with my other performance work. But this time it was not so much for the documentation of the performance itself but more for the idea of turning this into a video installation or some new work down the line. Most of my works, I mean all my works, are performance-based. And I’ve been thinking about this from the beginning — we all know that documenting something live is never the same. It’s the same with recording live sound — it is never the same as live. And I do think it’s very necessary, the documentation of a performance work. But I’ve always wanted — and I think this is something I want to do in the very near future — instead of simply documenting what’s happened, I want to be able to use a new artistic filter to filter out what the moment is like for everybody. When a journalist writes about a piece of music, the listening moment has already gone. What he’s writing down is what he remembers. And this is a creative process, very valid. So I felt like maybe this was a good path to take when documenting performance, or let’s say recreating moments. I’m just taking this moment through my memory, my archive of what I have, and I’m creating a piece that’s about what has happened — not just showing evidence of it having happened already.

AL: You are about to publish an extremely touching record of Tissues, as it happened at Tate Modern in 2019. How did you work on that, knowing that this could be seen also as a sort of document?

PD: Well, it is a record. It is also like a document. Let’s say the relationship between this record and these shows is like the relationship between a smell and a bottle of perfume. A bottle of perfume is a package, a possibility of experiencing something that is very subjective. That something is very special and has many, many layers that you know you can’t use words to describe. You can make music about this memory of the smell, or you can have a film about it, but the bottle of perfume provides access to the scent. So I felt like the record is an access point for people who did not have the chance to experience Tissues at the time — which I don’t think works with all my performance work. It’s just for this work, because it was a piece of opera. As with most opera, you either publish a film or release a record, because the music is at the core of it. I think probably the best way to give access to this memory is through listening. But there’s other material I’ve already used, some video footage. There are many possibilities for reconstructing the piece, but I never feel like there is a need to repeat something that’s already happened, or to recreate something that’s already happened. It’s only interesting to extract something that’s special and bring new life to it. It’s also out of respect for that moment. We all have this feeling where you eat something you really like. And when you go back to eat it again, suddenly you don’t like it anymore. We don’t want to re-chew something we’ve already chewed. I think that would invalidate that beautiful memory or moment that you have. I think the same with improvisation: if you do the same improvisation twice, then the second improvisation is dead inside.

AL: As a performer, as a solo musician being asked to tour in different situations, to commit to never repeating yourself is quite rare, if not unique. I always admired your strength. I guess it must be exhausting.

PD: I think for some musicians it is very, very exhausting. It’s very hard to keep every time different. I thrive from this exhaustion, this excitement that comes with the uncertainty, and I belong to that moment. When the chance is right, I will always perform because I need that. It’s something that gives me so much fuel and energy back. And I feel like if I don’t give a hundred percent on stage that there’s no point for me to be standing there anymore. That’s how I personally feel. But I also don’t disrespect or downgrade other artists who repeat the same set, because everybody’s music is different. Especially in pop, where there’s very little space to improvise in live performance. It’s much more of a structured work, and the audiences are expecting something different as well. On the other hand, I’m always really against this obligation to perform when there is a sense of “entertainment.” The last thing I want in any of my performances is that the audience is coming to be seen by the audience. It becomes a social dilemma. I want to break the boundaries between the spectator and the performer. I want the audience to feel that there is not one specific place they can look. There is always a directional thing. I want them to feel like the lighthouse is rotating. There is some sort of unavoidable intimacy, although uncomfortable in the darkness. In a way you’re trapped: you’re not under the spotlight, but you feel mentally uncomfortable; you start to look around and you’re not sure if you’re on stage or if there is a stage. And then you feel the space. I feel like that’s the only way the walls can be broken: the walls of the space itself and the walls between the performers and the audience and the walls between the viewer and the artist. There is a togetherness. And this togetherness cannot happen automatically in some circumstances. There needs to be triggers and force to bring something together. I put a lot of trust in the audience.

AL: You beautifully discussed the reception of the work, how your thinking triggers a specific way of receiving and how this way of receiving is driven by the environment and by the sense of belonging. Let’s talk about the compositional process instead: Tissues originated from an opera you wrote. Something that has a source, a text that becomes music, singers and performers, and then you somehow model the space and of course the performance as well. You worked with them for a long time beforehand. But then The Absent Hour arrived. And it wasn’t scripted beforehand. You just made it happen. Can you describe it a little bit?

PD: There were limited resources and only so much time. We did not document it as much. But it is, for me, a very important work. I think in Tissues, in all of my work, there is a sense of violence. I don’t know if that’s the right word. Because of my background, how I grew up, the environment that I was surrounded by has always been quite violent. I’m not talking about physical, emotional violence. So, I feel like because Tissues is a work about violence, I needed to confront myself through this work. This feeling of being trapped and being released together. On the other hand, because of this vulnerability, it needs this shelter, a place to, you know, feel gentleness and tenderness and bring people along with me to a different side of this emotion — which you can also experience through Tissues, but there is not a sense of tragedy. It’s much more neutral. It’s much more a form of confrontation with despair, a feeling of emotional stillness that you can hold onto for a while. I feel like The Absent Hour was growing within me during the process of making Tissues, and birthed when the time came. Again, for me, it was a lot fun. It was very playful. There were volunteer performers coming, there were kids running around, there were little girls, and we all were confused, everybody was lying around. The Absent Hour was like a first encounter with a stranger, and Tissues much more for the believers, who came prepared to face something.

AL: The Absent Hour took place in an almost semi-dark environment. Shades of light were moving around, following an uncanny pattern, and defining the large former oil tank as a kaleidoscopic and shapeless underbelly. Such a light, such an ambiance never happened before in the eight-year life of that specific environment and that’s why the whole turned out uncanny. There were also bodies moving in the space, quietly, and there was a soundtrack, an overarching composition that had extreme moments driven by voice – oscillating between lullabies, lamentations, voice rehearsals, whispers and animal sounds, as barks – and moments driven by music only.

PD: Whilst in Tissues it feels like you walk into a nightmare, like a tragedy, like a big nightmare, in The Absent Hour it is like you’re dozing off during the day, but in the dark. Like dozing off on a cloudy day in November. Or butterflies. It’s interesting because to describe it in an obvious way is very different. My role as a composer is not just composing music: my methods of composition apply to all the elements in my work: it’s my composition, my performance, my visions and my sound. Making Tissues gives me resources that become elements I could put into The Absent Hour. That work is based a lot on, let’s say, human senses — how we want to feel, or how I want them to feel in a way.

AL: You mentioned butterflies, I was seeing fireflies.

PD: Fireflies, exactly. It is really important to remember that no matter what, there is still a place of purity and innocence that we need to protect in our humanity, in all the work in this world, and that needs to be felt and shown when possible. I don’t think Tissues would be complete without The Absent Hour. Because there were childlike moments, moments of innocence in Tissues, though it was still very tragic because it was already entering that tunnel.

AL: In a museum the main question has always been how do you differentiate between spectacle and artwork, the given time and the walkaround time: You pay, you enter, you experience, you leave, versus you enter, you encounter, you didn’t expect it, you leave. But then, that encounter is not authoritative as a spectacle would be: a spectacle, or a gig, has the power of being staged and being already acknowledged as an authority. Whereas the encounter is actually something very profound. I think in The Absent Hour that was very much at stake. It’s a choice you made: you didn’t want the public encountering The Absent Hour to belong to a style, or to a mood, or to feel a sense of belonging. This is quite radical because it’s somehow an anti-community proposal.

PD: I would probably feel like shit for the next ten years if it was anti-community [laughs]. I mean, I have a different conception of community, not based on background, education or social circle, but on a deeper connection, creating an unbiased space for sharing. But if I’m doing the right thing that I think I should be doing, I think I’m creating something that will bring things together in the long run. I just need a lot of patience. The process can be a lot of suffering because it requires me to be very, I don’t know… resilient. It’s not very rewarding sometimes, but there are other rewards. This whole world has become so artificial and superficial that it’s quite distracting at times. You have to really maintain where you came from to be able to resist that. If you’re facing a path, you cannot just take a shortcut. I feel that way.

AL: Some practices, very few ones, as yours, end up being extremely in tune with reality — really dramatically tuned but also beautifully tuned. Suddenly, everything that has to do with that idea of community you mentioned becomes representational and loses meaning. The alternative is something perhaps extremely troubling, yet personal, pristine, authentic. I’d call this the sublime déjà vu: everything unfolds like a déjà vu. Audiences encounter your work with a dizzying sense of déjà vu, and that may cause pain. In a nutshell: you encounter, you see, you listen, you’re afraid, perhaps even terrorized because you don’t know where and when it already happened. Were you there? Could you change it? Anxiety mounts. Of course there’s also an addiction to that déjà vu, somehow you want it to happen again. Artworks constructed on a representation level work totally differently. But in your own work, it’s like you want to make people feel alive.

PD: The kind of community I want to create, is one in which people are able to resonate with a particular feeling and open up to these experiences. That for me is the most precious connection one can have. To be able to find this community, one has to be honest, brave and vulnerable at times. I want communities to gather around the experience of the work, through this they find each other. I think that community comes from a much larger place. It just takes a longer time for us to find each other.

AL: I think that’s true. And it’s based on belief, on trust, but also on chemistry, like chemistry as a composition of sound – or a déjà vu, a smell, a gaze, like whatever, like a touch of softness. I mention chemistry because I think about the acid corrupting and therefore affecting the change of color of the steel. In the end, that’s chemistry, as a process of transformation.

PD: I mean, it’s also human instinct. If we are lost in the jungle, no matter if we are mentally lost or physically lost, at the end of the day all we have is our intuition, our instinct, our human nature. And that’s why you rely on your senses. Hunger doesn’t matter. Anger doesn’t matter. Of all these things that you’re talking about, that feeling of déjà vu is what we are most familiar with, but also most scared of.

AL: Intriguing, you’re shifting the conventional structural understanding of transformation to something less graspable, intuitive perhaps.

PD: Definitely. I guess that what I’m trying to say is this transformation is an instinctive choice. We know our existence could go beyond our physics and we know it’s so powerful that we are afraid of the potential of these transformations.