Some exhibitions conjure a mental soundtrack. The New Museum’s survey of art made twenty years ago, “NYC 1993,” includes one in its subtitle: Sonic Youth’s Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star (1994). Although Sonic Youth maintained a DIY ethic, the unprecedented success of their third major-label release inspired tense debate about “alternative” rock’s shift from an underground scene to a marketable subgenre. Indeed, all markers of politicized identity became subject to rampant commodification in the early ’90s, while debates swirled about arts censorship, racial tensions, women’s and gay rights and the AIDS crisis. Appropriately, many of the artists in “NYC 1993” grapple with these charged topics.

Rather than narrowing their focus on a single theme, the curators offer a complex portrait of the year through its exhibition history, beginning with Devon Dikeou’s What’s Love Got to Do With It? (1991-ongoing). Dikeou’s series of bulletin boards document the titles, dates, locations and artists in all the group exhibitions in which she has shown — a micro art history through the lens of a single artist. Her 1993 CV spans a show at PS1 to a raucous-sounding hotel exhibition called “Trancesex.”

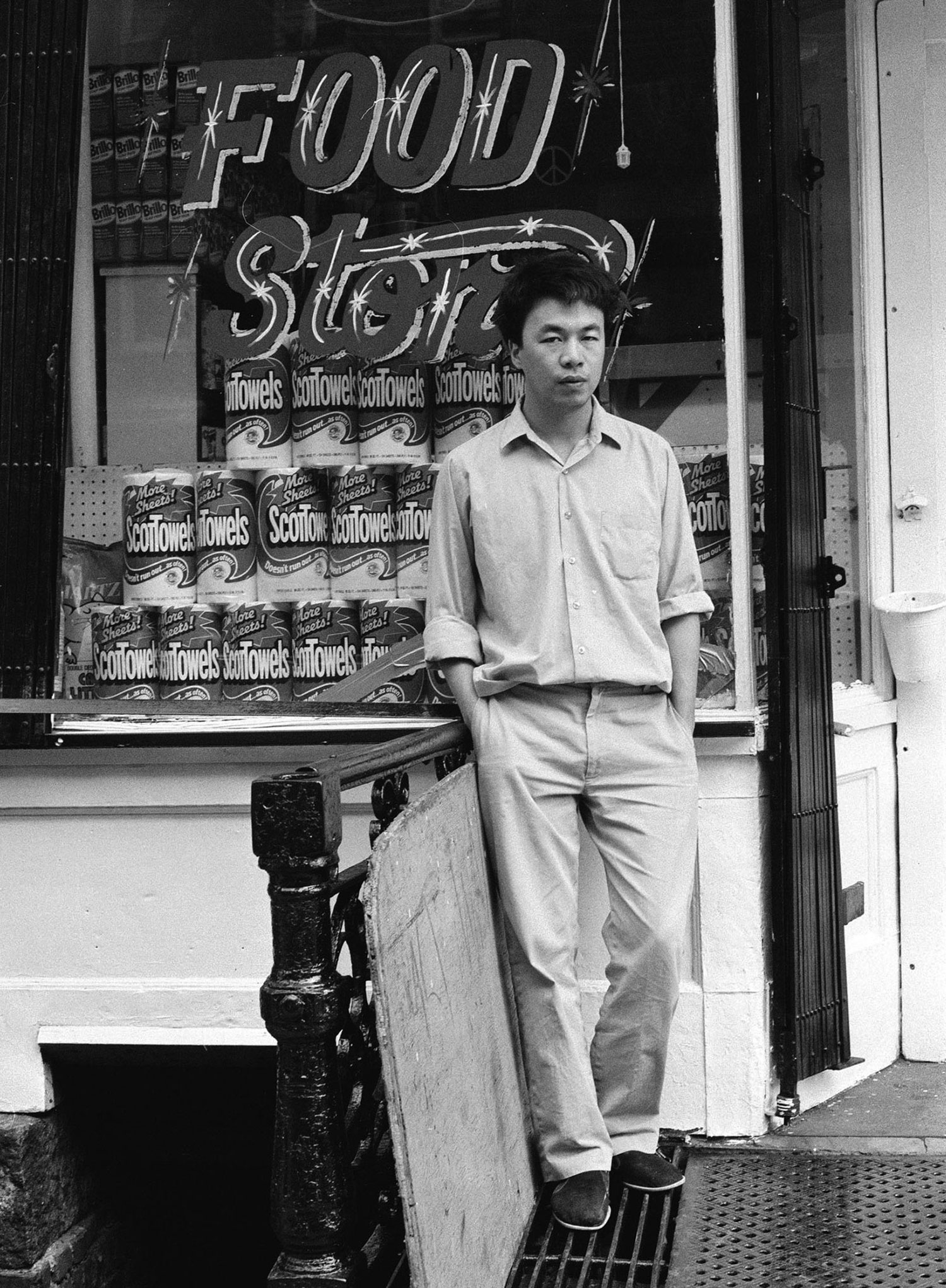

Ironic posturing with youthful aesthetics informs the conceptually rich works of artists Wolfgang Tillmans and Art Club 2000. Tillmans’s staged yet casual portraits of friends like Moby and the art/fashion collective Bernadette Corporation circulate between exhibition and magazine constructs in new configurations, while Art Club 2000’s photos in shoplifted Gap clothing interrogate the language of advertising and pre-packaged subcultural identity for an art audience.

But the identity politics-influenced work of the early ’90s takes pride of place. Gregg Bordowitz’s video Fast Trip Long Drop (1993), a meditation on the artist’s own struggle with HIV and media discourse around AIDS, and Andres Serrano’s morgue photographs, which obliquely reference the disease, balance angry political sculptures by Cady Noland and Nayland Blake. The exhibition pays homage to the rising stars of the 1993 Whitney Biennial, excoriated for its explicit imagery and angry tone. Janine Antoni’s Lick and Lather (1993), gnawed self-portrait busts in chocolate and soap, and teenaged Sadie Benning’s black-and-white diaristic video of queer desire, It Wasn’t Love (1992), retain their feminist edge. Daniel Joseph Martinez’s commissioned Whitney museum tags bearing the phrase “I can’t imagine ever wanting to be white” are a thrill to see (but unfortunately are not reissued as admission badges.)

For true catharsis, see Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s billboards of birds across a cloudy sky (Untitled, 1992-3) and hanging light fixture (Untitled (Couple), 1993) on a plush orange carpet by Rudolf Stingel (Untitled, 1991/2012). Accompanied by Kristin Oppenheim’s lulling a cappella loop Sail on Sailor (1993), this grouping of work recalls the pain of loss reverberating in the backdrop of powerful representational statements by the artists on view.