Madness and Reason in the Minimum Security Studio

Madness and Reason in the Minimum Security Studio

by Gea Politi

Visiting Sterling Ruby’s studio in Vernon, California, you are tempted to trash part of it or to make it even messier amid the “vast amount of garbage” parked there. The outdoor space is full of “junk,” so to speak. All these fragments, pieces, utensils and basins will one day become Sterling’s artworks: whether massive phallic sculptures, dripping with urethane; nail polish paintings in which he questions issues of gender and transgression; his infamous spray-paintings; sculptures of smudged and scratched white minimalist forms; mammoth-sized cages on wheels; videos of male porn stars masturbating non-stop; or “soft vampire’s teeth.” In recent years, instead of embracing an easier aesthetic, Ruby’s has grown stranger.

Given the fact that all that garbage is good garbage, I find myself looking at an unfinished urethane container, still in yellow foam with sharp objects sticking out. I try to raise the question, “Is this…?” Sterling interrupts me with a simple, straight answer: “No, that’s nothing.” Wondering whether Ruby’s work is “extremely American” is a thought that invariably crosses one’s mind when visiting his studio. In 2008, Ruby had his first exhibition at MOCA, titled “Supermax,” which evoked the feeling of being behind bars.

Sometimes I think this whole world

Is one big prison yard

Some of us are prisoners

The rest of us are guards

Bob Dylan, “George Jackson,” (1971)

The world of Bob Dylan was just so simple. Time waits for no one and meanwhile we get a bigger picture. A book called Total Confinement: Madness and Reason in the Maximum Security Prison takes us into a hidden world that lies at the heart of these prisons. Focusing on the “super-maximums” and the mental health units that complement them, it conveys the internal contradictions of a system mandated to both punish and treat. And that’s only a part of it. Sterling’s work is as complex as the American empire. It addresses numerous topics, including aberrant psychologies (particularly schizophrenia and paranoia), urban gangs and graffiti, hip-hop culture, craft, punk, masculinity, violence, public art, prisons, globalization, American domination and decline, waste and consumption.

While glancing through his drawers, in a place designated as the “research room,” I had a stroll down memory lane similar to when I saw a documentary on Stanley Kubrick’s unveiled archive. Each drawer contained an exhaustive, fanatical investigation on topics such as war, hospitals, prisons, murder scenes, and objects of all kinds, from guns to porn magazines. Each of these topics are clearly referenced in Ruby’s work, in a manner both blunt and subtle. Let’s take the undoubtedly attractive spray-painting SP#, a schizophrenic night-vision battlefield. Most of the time. Horizontal lines determined by changing colors, from green to pink, from blue to red, might define good and bad, the rise and fall of an empire. A horizon that doesn’t see clear light.

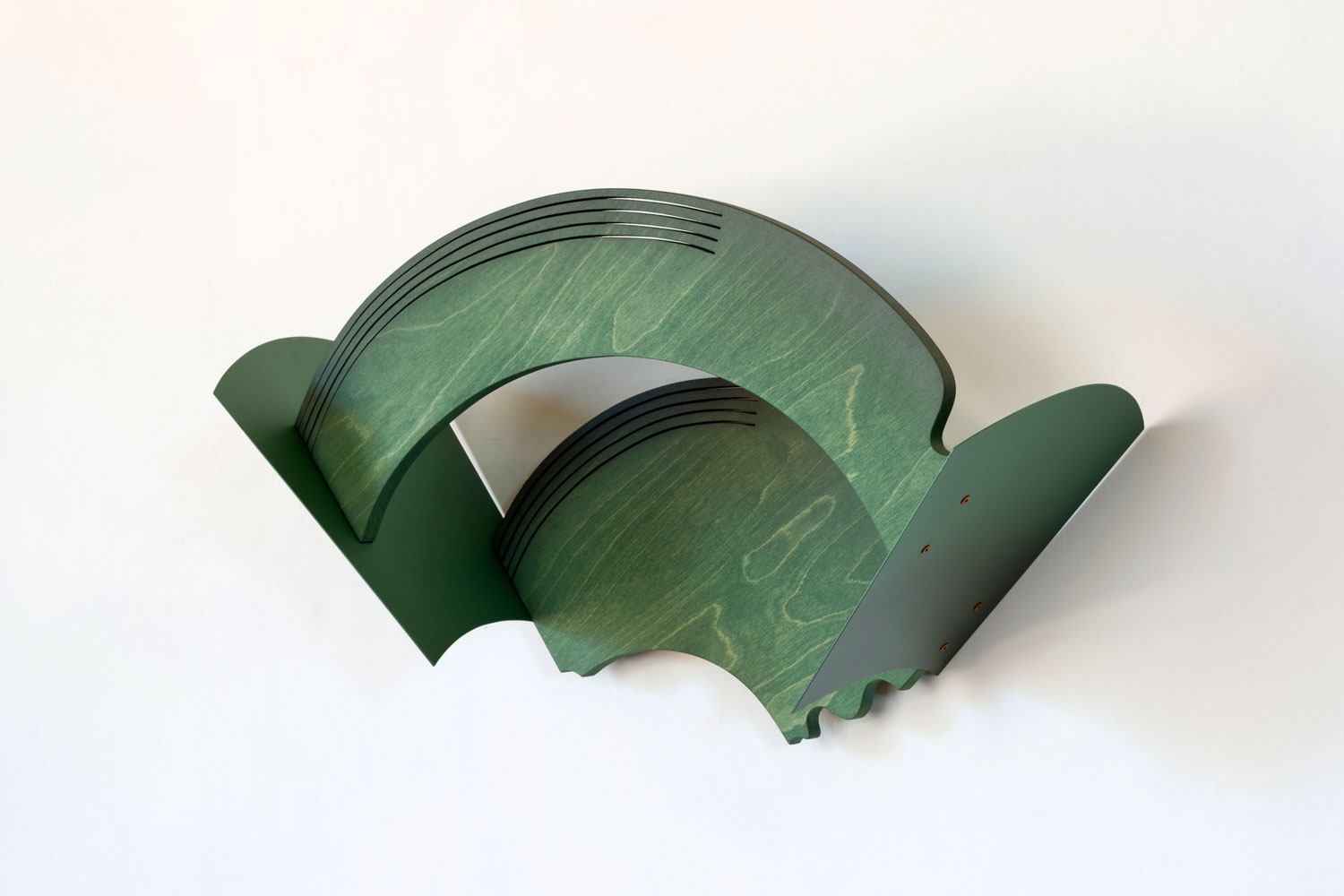

The current studio is 16,000 square feet. It is divided into areas for collage, ceramic, urethane, painting, fabric collage, woodwork. Metal works and large sculptures are made in the yard. As for collage, Ruby has similar intentions whether the materials are fabric or photographic. Although the result may look different — the textile collages are usually huge, while the photographic ones are much smaller, with cut outs of ancient buildings, aquatic paraphernalia, stolen internet images — the processes are similar. Sterling visits each room daily, and works simultaneously on every set. And this brings us back to the artist’s construction worker period.

Young Sterling took a foundation course in art in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he learned the visual basics like perspective, color, composition and form. After four years of nothing but still life, colors mixing and additive and subtractive sculpture, the urge to switch completely to theory came natural. Ruby took psychology courses in order to develop a more premeditated approach in his modus operandi — which ultimately led to confusion and no degree.

There is just too much information for anything to be coherent or whole.

The outcome of this post-situation (post-anxiety, post-cynicism, post-transgression, post-depression, post-war, post-law, post-gender, ect.) is a sense of adjustment or coping. It certainly doesn’t feel like anything other than a strategy for survival. Sterling Ruby thinks that he applies a kind of “transversality,” not only in theory, but also as a work ethic.

Bob Dylan again:

Now, it’s all been done before

It’s all been written in the book

But when there’s too much of nothing

Nobody should look

In Sterling Ruby’s world — encompassing sculpture, drawings, video, ceramic and painting — everybody should look. His aesthetic is captivating. And his art is poetry, maybe it can’t be proved but yes it is.

The Los Angeles Immortality Project

by Emi Fontana

The first time I heard Sterling’s voice and name was almost fifteen years ago: the phone was ringing at Mike Kelley’s studio, in Highland Park; it was after hours, so I picked it up. Sterling’s voice was kind and his name was sounding — he was Kelley’s teaching assistant at Pasadena’s Art Center College of Design at the time.

In 2005, I went to take a peak at the MFA graduation show at the Art Center. Wandering in the Del Mar studio, my attention was caught by a video installation: on the screen everything is in mute, nondescript shades of beige, suggesting institutional decor and corporate anonymity; a guy, wearing clothes that are the same color of the environment around him, is having a tantrum. He is throwing himself on this soft, cushiony surface, producing regressive sounds that are painful to hear — that clearly belongs to a much earlier stage of development than that of a grown man. The cries express frustration and some kind of deprivation. The young man in the video is progressively extracting a series of objects from the soft structure : a model house, an abstract pink ceramic, some devotional kitsch, a piece of fake marble, and a book: The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker. Written in 1973, the essay analyzes the sophisticated ways in which human beings enact their defense against physical death, by embarking on what Becker refers to as the “immortality project.” The video I was watching was titled Tamper Tantrum/Inanimate Death Magician, and the author’s name was Sterling Ruby. At that point I had forgotten about the phone call, so I scribbled the name on my note pad. Later that evening, I talked with Mike about what I’d seen. “Sterling was my TA, and one of the best students I ever had,” he said.

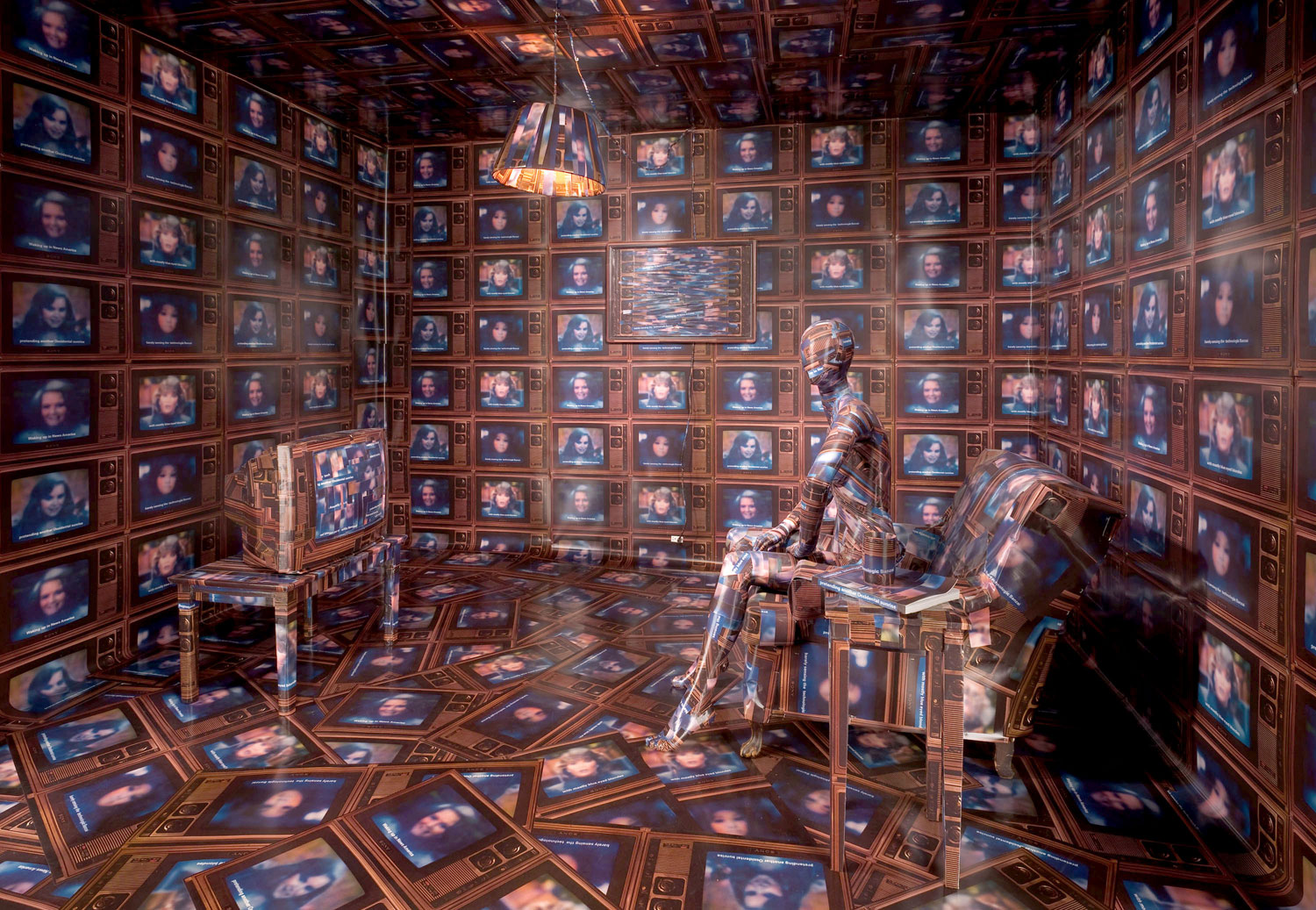

Eight years later, the world could have not being more different under the bright Southern California sun. After graduation (he never formally graduated, actually) from Art Center, Sterling started his escalation on the ladder of the art system, getting to its core and playing its edges. The work, combining and recombining in an ever-changing magmatic blob of forms, styles, media, material and colors, embodies a never-ending battle between minimalism and maximalism — a battle that the art crowd seem to follow with the avidity and devotion of a bunch of hooligans watching a grudge match. In 2007, Sterling had concurrent solo shows at Metro Pictures and Foxy Production. For many, this scenario would be a point of arrival; for Sterling it was just a stepping-stone toward something else. The show at Metro Pictures was very dramatic, almost funereal. Sterling’s mother had died unexpectedly not long before the show; a Zen meditation fountain that had belonged to her coincidentally inspired one of the pieces in the exhibition. At Foxy Production, he presented a video installation titled The Masturbators. The viewer was surrounded by life-size video projections of nine different men — professional porn actors — masturbating. Just three of them manage to reach climax, what in the porn industry is called the “money shot.”

Ruby’s work and carriage seemed to be informed by some kind of post-punk and post-Situationist strategy to fulfill “the demand to live, not as an object but as a subject of history.” Soon after the New York climax, rumors circulated about Michael Ovitz, renewed Hollywood tycoon, agent and art collector — obviously well versed in illusions of grandeur and broken dreams — starting to represent artists; the first name to surface was Sterling Ruby. It is not clear how Creative Artists Agency works with the art system, but Ovitz was really close to Pace Gallery, and so Sterling packed up from his brief stop at Metro Pictures to join the stable of Pace — but not for long. About a year later, Pace’s employees were abruptly told to cease any kind of communication with the artist’s studio and with James Lyndon, one of Pace’s former directors who was in charge of Sterling’s account. The circumstances of the break up are still unclear and kept confidential.

In the meanwhile, Sterling’s work has grown bigger and bigger. Today, his studio is a huge compound in east LA. In recent years it has become one of the most exclusive and desirable destinations for art collectors — you can almost hear the shivering voices of consultants whispering in their client’s ear: “We have a studio visit with Sterling Ruby tomorrow!” The ascending parabolic trajectory of Sterling’s career provides good material for a case study about the dramatic changes that have occurred in the art world over the last ten years, especially in Los Angeles. This city, always known for its very active, often radical and cutting-edge artistic community (one of its blessings is to be sheltered from the competitiveness of the New York art world), is becoming the laboratory and the vitrine for those changes.

On January 31, 2012, Mike Kelley completed his “immortality project,” forever closing his bathroom door in the face of an incredulous art world. At the end of the same year, Hauser & Wirth signed Sterling as one of the gallery’s artists. Paul Schimmel, legendary curator of “Helter Skelter,” the show that contributed to forging the image of Los Angeles as a mecca for new creativity, became a partner with Hauser & Wirth and therefore had to leave his position at the Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts in order to open the gallery’s Los Angeles branch.

Sterling is about to move into an even bigger studio, basically the size of a village. The immortality project is still spinning.

Sweet Black Angel, or the Fictional Impulse

by Sam Falls

Blood Meridian, or The Evening Redness in the West, which I’m presently reading, would make a great title (if not already in use by Cormac McCarthy, obviously) for an essay on Sterling Ruby. Last night I was driving home in LA, heading down Lincoln Blvd. in Venice, and there was a semi-homeless guy reading a newspaper on the stoop under a store’s outdoor light, nobody around, and it looked really pleasant, the perfect temperature and time to catch up on the day’s news. They were paving the streets, so there was traffic, and I had time to relish this juxtaposition of a kind of homeless “old man river” reading on one side and the young bucks working diligently for the public through the night (both sort of shitty positions to be in, I understand, but sometimes it’s good to stay on the surface). I was listening to Sweet Black Angel right then and thinking of writing about Sterling Ruby. What to title the piece seemed like a good place to start, and this song made sense. I rewound to hear where Mick Jagger starts:

Got a sweet black angel

Got a pin-up girl

Got a sweet black angel

Up upon my wall

Well, she ain’t no singer

And she ain’t no star

But she sure talk good

And she move so fast

But the gal in danger

Yeah, the gal in chains

But she keep on pushin’

Would you take her place?

So I’m listening to this and thinking about skinny, white, British Jagger. I’ve seen enough rockumentaries to be fully bored by the Stones’s fascination with the blues and American music, but I guess I never paid attention to this one song’s words and the total fiction he was imagining to come up with these lyrics. And then, watching the road crew sweating in a day-for-night setting while the homeless guy eases into the weekend while I’m in the car slowly listening, slowly observing and thinking about Sterling Ruby, it all makes sense. In Ruby’s work there’s fictionalized exploitation, there’s non-stop labor, there’s ease, there’s a comfortable homelessness, there’s sweetness and darkness, and there’s a consistently translated observance of place fictionalized to something more American than America would admit.

Sometimes the problem with being an artist is you begin to envy music and writing, poetry and rock ‘n’ roll, because of its immediacy, simplicity and specific/finite tool set. There’s a quicker resolve between idea and materialization, and the literal materiality that transports ideas plays less of a roll in the translation from writer to reader, or musician to listener, than artist to viewer. Now artists have to struggle with objecthood — it is again a critical issue today, as it was in the ’60s — and not addressing it is seen as neglectful for young artists. As a viewer of Sterling Ruby’s work, I’ve encountered the reciprocal end. Often it’s a massive artwork that comes to mind when you think of a Sterling Ruby, and if it’s not large it’s at least heavy and dark (I’m thinking here of the ceramics). But when I moved to Los Angeles from New York a couple years ago in search of open space and time to work, I think the Ruby objects receded like a sunset into the ocean, you know? The sun is huge but small and elegant relative to the crashing waves as you stand on the beach. Put simply, it’s all relative. I could adjust to seeing the artworks as natural progressions for an artist working in LA, as well as their true symbiotic nature. Ruby’s work suits LA, it’s comfortable in its skin, because its guts are all the shit that make up this city. I have to drive on a highway every day except Sunday, and I probably pass at least five eighteen-wheelers on the way to the studio and five more on the way home. I see asphalt being poured, sheets of cardboard and scrap metal blowing along the highway, planes and helicopters are constant, dumpsters are overflowing everywhere, and, just generally, this large intrusive shit is all second nature. Scale is different in the West, and industry, along with its residue, is right outside your door. In this context Sterling’s work lost a lot of its shock value, which separated me from it for a while, and with that recent divorce came an acknowledgement of its depth and beauty. That said, I always recognized there was something grand happening with his work, but it always seemed too dirty in both content and aesthetic — too shameless in its glorification or fetishization of counter-culture. In my mind it seemed unreal. Now I realize that it truly is unreal because it’s intelligent, and our conditioning to this sort of “found” fetishization in New York over the past decade was just a polishing up of a lot of previous work, rather than a development and creative examination of the American condition, the poetry of art and the righteousness of being true to your home break.