“Prayer is all about address,” Gregg Bordowitz writes. “It’s about giving an account of oneself to another, and being other to another.”1 Risking awkwardness for relation, Bordowitz likewise gives himself to his audience. Perhaps foremost recognized for his work with ACT UP and the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in NYC, since the 1980s his practice has long involved diverse modes of oral, textual, and visual address. Conceived as the second chapter of a partner exhibition at Bonner Kunstverein, “There: a Feeling” honors the permutations and poetics of Bordowitz’s voice, “together adding up,” he notes, “but never summing up.”

Addressing “the danger of the stage,” on the opening night of his exhibition, Bordowitz delivered a casual, lecture-lite performance. Speaking to “what is meant and how one means,” he offered an angle on work that has encompassed activism, poetry, film, performance, publishing, and teaching. Surveying the audience, he later admitted, “I am wanting to say something that I cannot say.” Attentive to the weight of the unsayable or unanswerable, Bordowitz’s “sloppy minimalism” happens within the indefinite continuum of faith. “My job is to unfold questions out of questions.” Such work relaxes distinctions between word and image, thought and emotion, allowing reflection on how we arrive at the substance of feeling as such.

The exhibition’s open terrain or “holding environment” à la D. W. Winnicott (that realm of creativity and transition) is established by a slim red line. It runs three inches above the floor, delineating the inside walls of Camden Art Centre’s galleries. Contouring the exhibition in a circulatory frame, it takes the architectural pulse of the institution while demarcating the territory within which art is to exist. A limit every viewer must transgress to engage among other relational objects, the line’s abstracted tension spatializes presence. Holding binaries of inside/outside, here/there, enclosure/horizon, the line, increasingly destabilized of purpose, is a boundary that bleeds.

This instability of protocolled form finds its counterpart in Debris Fields (2025), an all-caps poem of twenty-four verses. Its stanzas wrap the hallway in delicate vinyl. Composed solely of nouns, each line ten syllables, the verses’ self-same dimensions modulate the interstitial passageway with memorial resilience. Rigid yet absorbent, nouns are plastic units; Bordowitz construes their items and ideas into forms marbled and measureless. Elasticizing the noun as freeform material, the walls become stratified by limitless texturality, bursting aura into anti-aura, rupturing novelty into sublimity. Everywhere does cracked syntax give gnarly frisson: “CONGRATULATIONS MORBIDITY,” “CANDY AROMA POPPERS KITCHEN TABLE.” Other unvarnished adjacencies express fleshly or whacky sibilance: “SPOTS SCORES SORES SURGERY SARCOPHAGI,” “SEQUINS CINEMA SANCTIONS ASSASSIN.” In this semantic opalescence, concretions of thought and feeling dazzle and dull the mind. Wandering its magnificent quotidiana, the epic litter of artifice strews countless narratives without resolve as to where debris ends and field begins. Rigors of pleasure as much as exhaustion, “WORDS EMPTINESS SIGNIFICANCE LETTERS,” these nouns testify that feeling might be the highest truth.

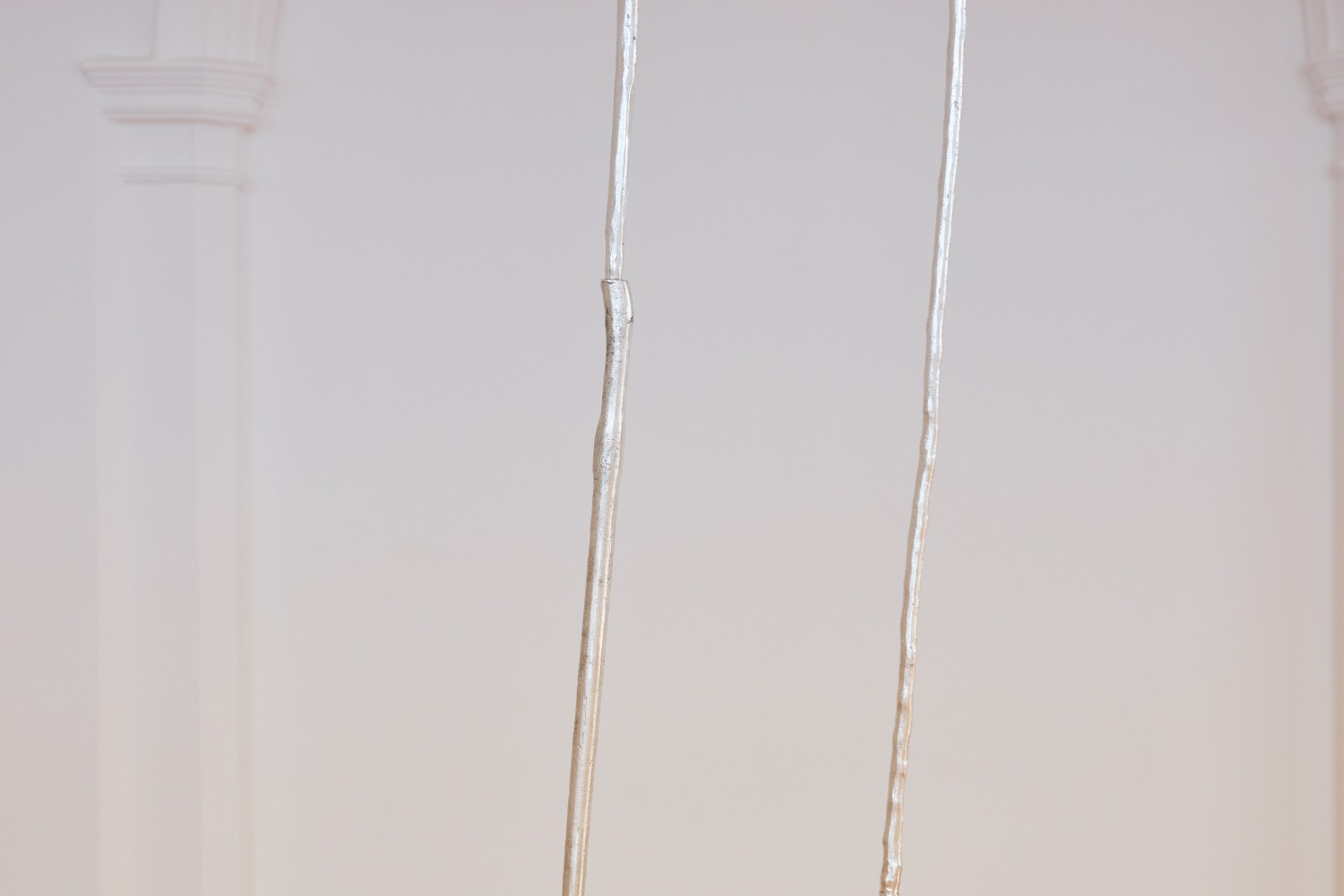

In the main gallery, Bordowitz’s monotype prints (Tetragrammaton (Camden), No. 1–12, 2021) continue the rhythm of ritual through meditational practice. Each limns the unspeakable, as Bordowitz describes in the supporting literature, “an ineffable, unpronounceable four-letter Hebrew word, the name of G-d in Judaism that spells creation into existence daily.” Collapsing word and image, yellows, pinks, browns, blacks, and purples collectively riddle and rhyme this impossible figuration. Seven large wooden tree guards, upon which the monotypes are mounted, avow this dailiness. Sourced from Bordowitz’s native Brooklyn streets, the structures permit the ineffable to be encountered as incidental; divinity made neighborly. The heaven-sent streetscape is surrounded by Baroque Clouds (2018–ongoing), a floating frieze of plaster sculptures, their lofty heights realized like wonky soapsuds. Cloud as composure, as phenomena, as character, thoughts bubble-up beyond their mundane form.

The exhibition’s embrace of obliquity and absence delivers alternate views on history. Its title is from a line of Paul Celan’s poem “Homecoming” (1955): “There: a feeling, / blown over here by the icewind, / fastening its dove-, / its snow-coloured flagcloth.” To fasten feeling is to weather the accumulation of absence, “the sledtracks of the lost.”

Responding to Celan is a wall painting that features an excerpt from Hilda Doolittle’s (H. D.) 1944 poem “The Walls Do Not Fall.” Written following the London Blitz, Doolittle similarly penned persistence through devastation and the possibility of a continued reality therein: “we noted that even the erratic burnt-out comet / has its peculiar orbit.” The words are painted slantwise, recalling Celan’s notion of the poem as a “still-here” presence at an “angle of inclination” – to which her excerpt replies: “the angle of incidence / equals the angle of reflection.”

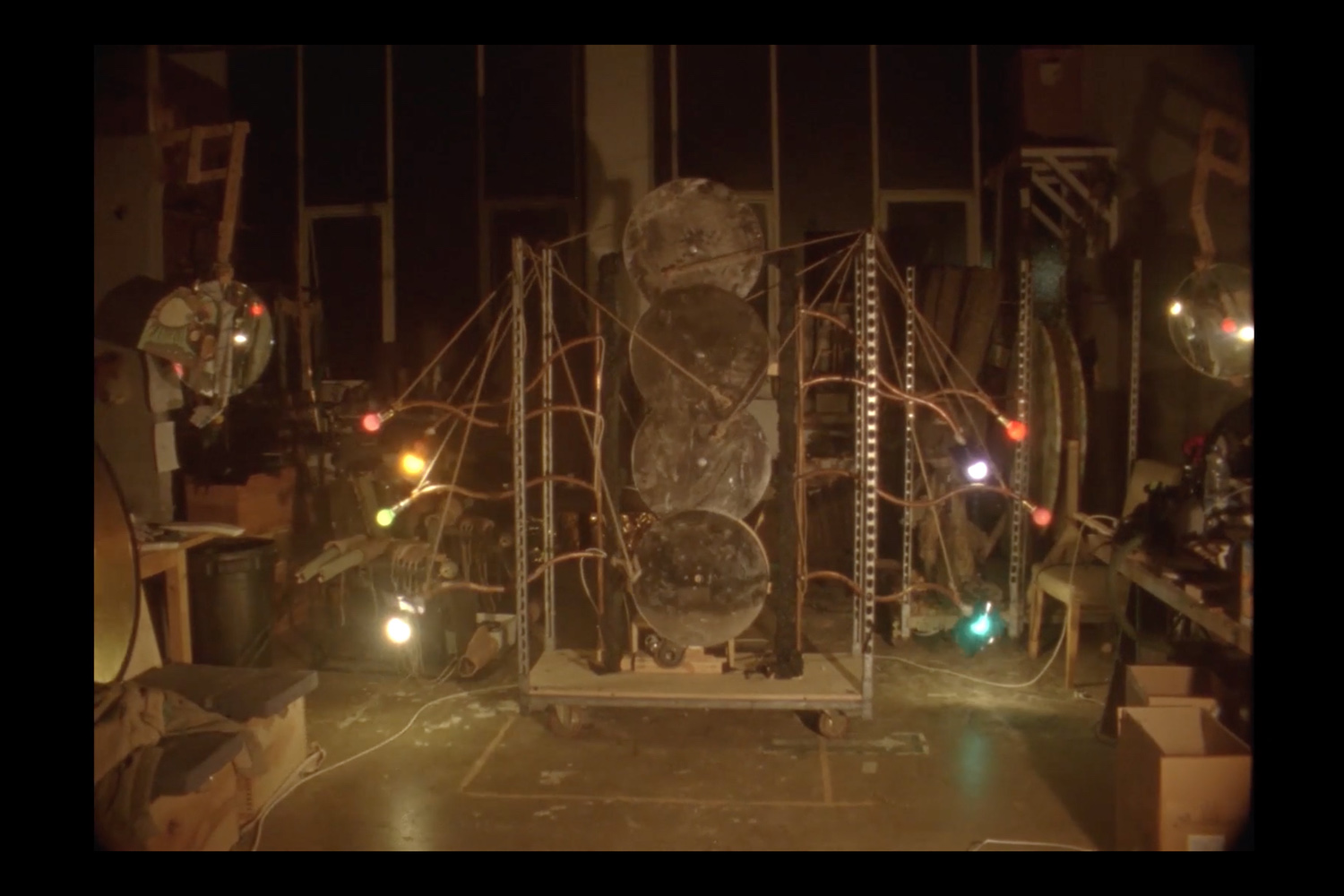

Before and After (Still in Progress) (2023–ongoing), the most recent installment in a trilogy of “autobiographical documentaries,” is shown in a black-box room. In seven acts of varied modes of address — lecture, poetry reading, stand-up comedy, song, and a Yom Kippur sermon — Bordowitz performs a many-faceted self that pluralizes his self-description as a “New York Jew pinko queer with AIDS.” Each chapter is intercut by a distressing clip of an elderly man asleep in a hospital bed, his breathing heavy and crepitant. Life meets death in a naked break. Having lived with HIV for thirty years, Bordowitz is intimately aware of the forces of life and loss. In a poem published in the exhibition booklet, he writes: “level horizons regard each other,” “singular life holds singular death.”

In one performance, Bordowitz meditates on the belief that “art can change the world” – words most attributable to the compelling mundanity of Portraits of People living with HIV (1993). In one portrait, a man with whippet in tow describes his care for an aviary of canaries, each bird numerically named Sweet as Pie (1, 2, 3, etc.) – an index for lives that will come and go. Later, he untangles a small pink rose from a chain-link fence and gifts it to Bordowitz behind the camera, quipping: “It’ll be dead in two seconds.” In another, a young man shares the tranquility of his rural surrounds: gasping, he lunges to cradle a stag beetle upon his thumb; overturning a chunk of deadwood, he reveals a brilliant red eft. Each portrait’s incidents of notice are foraged from matters of closeness, as Bordowitz writes, of “really feeling what it is to observe.”2 In a portrait titled “Boat Trip,” a group of friends that function foremost as a HIV support group learn to rediscover joy and intimacy among one another. Conscious of his mediation, Bordowitz admits a need to uncover the trip’s meaning, to discern some truth. As it turns out, faith exists in experience.

“Novelty is a feeling,” Bordowitz has written. “I believe there is genuine novelty in the world,” he affirms in his essay “More Operative Assumptions” (2003). “Truly new things, conditions, and relations do arise.” These artworks contain both the act of poesis and its material residue, that which holds the possibility of newness, of novelty, of faith. This promise of possibility is important. To observe with feeling the textures of the present tense, the is of things, requires significant effort. Bordowitz’s empathic relationality, in action and sensation, sustains unflinching realness as much as it restores belief in newness.