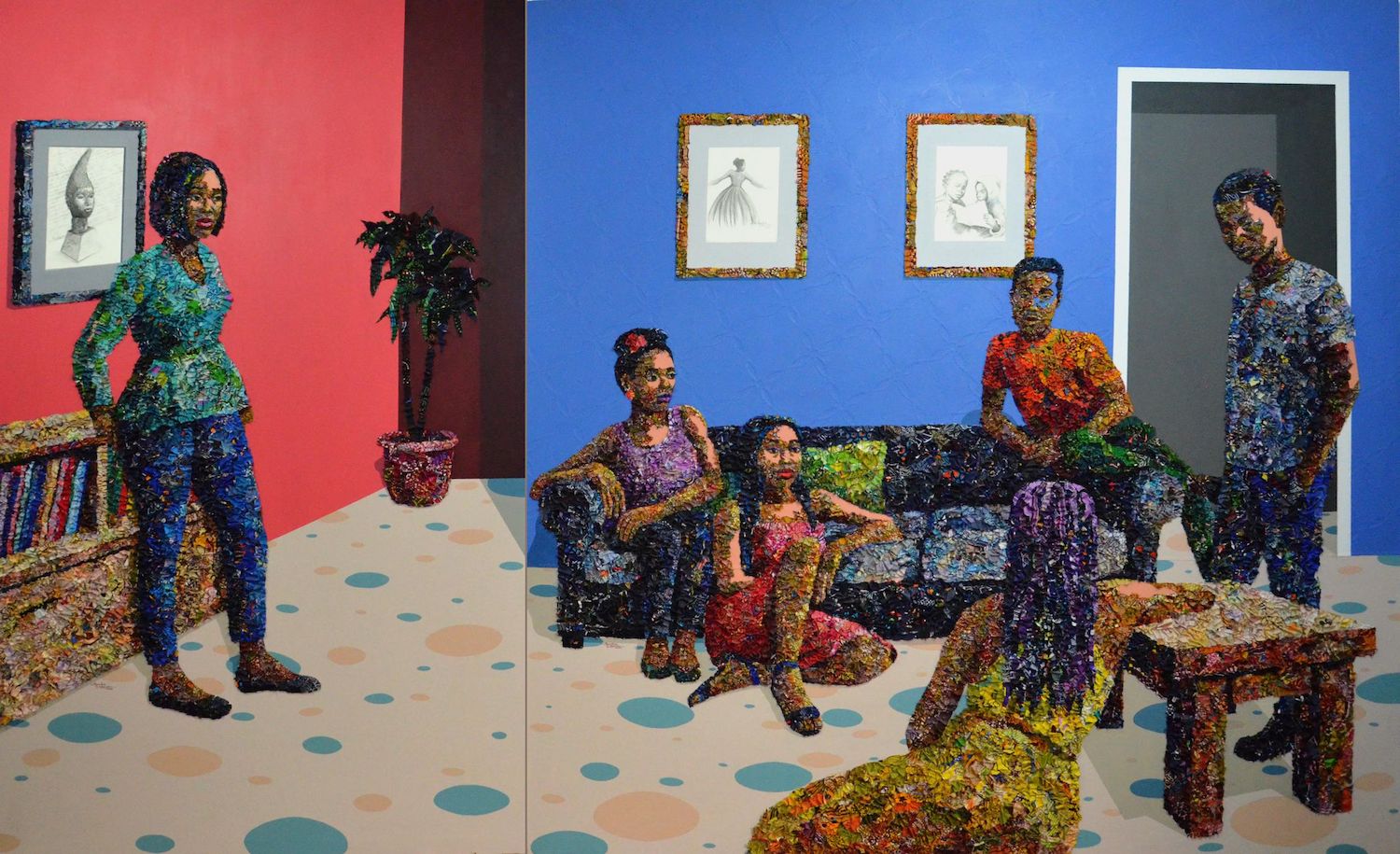

Tasneem Sarkez’s “White Knuckle” marks the twenty-two-year-old artist’s first exhibition in the UK. Six paintings are hung amid two sculptures at Rose Easton Gallery in London. Visitors are subsumed into a painted mind palace of advertising ephemera and digitally altered images. Their commonality: Sarkez’s exploration of symbolic politics between the MENA region and the US. Her subjects range from the everyday (skin whitening soap) to the nationalistic (bald eagle), offering a layered critique of cultural semiotics.

Sarkez’s work is immediately striking for its contemporaneity. Each work is a collage, an amalgam of images sourced by the artist from “IRL” and online. These canvases simulate the internet experience of viral memes steeped in kitsch aesthetics and AI-generated images coughed up by platform algorithms. High Tea (2024) depicts a traditional Turkish ince belli (literally “slim-waisted”) glass collaged across a kitschy red rose, which in turn contains the ephemeral and heavily kohl-lined eyes of a woman. Sarkez knowingly borrows from the traditional imagery of a sixteenth-century Dutch vanitas to lend her work a visual veracity – a time when painters explored contemporary capitalistic practices through still life. See Abraham van Beyeren’s Still Life with Lobster and Fruit (c. 1650): Sarkez employs an old master technique, contrasting symbols of opulence against a black background. Crucially, the artist’s erudite use of oil paint undermines any trappings of cheapness associated with “web imagery” or the fast-paced production of memetic content. The richness of oil lends the works magnetism, blurring the line between a traditional patina and a plastic, TEMU-grade sheen. Oil paint’s knack for building thin layers approximates Photoshop’s superfine blur tool — translating moments of the digital uncanny — while lending Sarkez’s paintings historicity. Even as we admire her technicality, we can doubt the image.

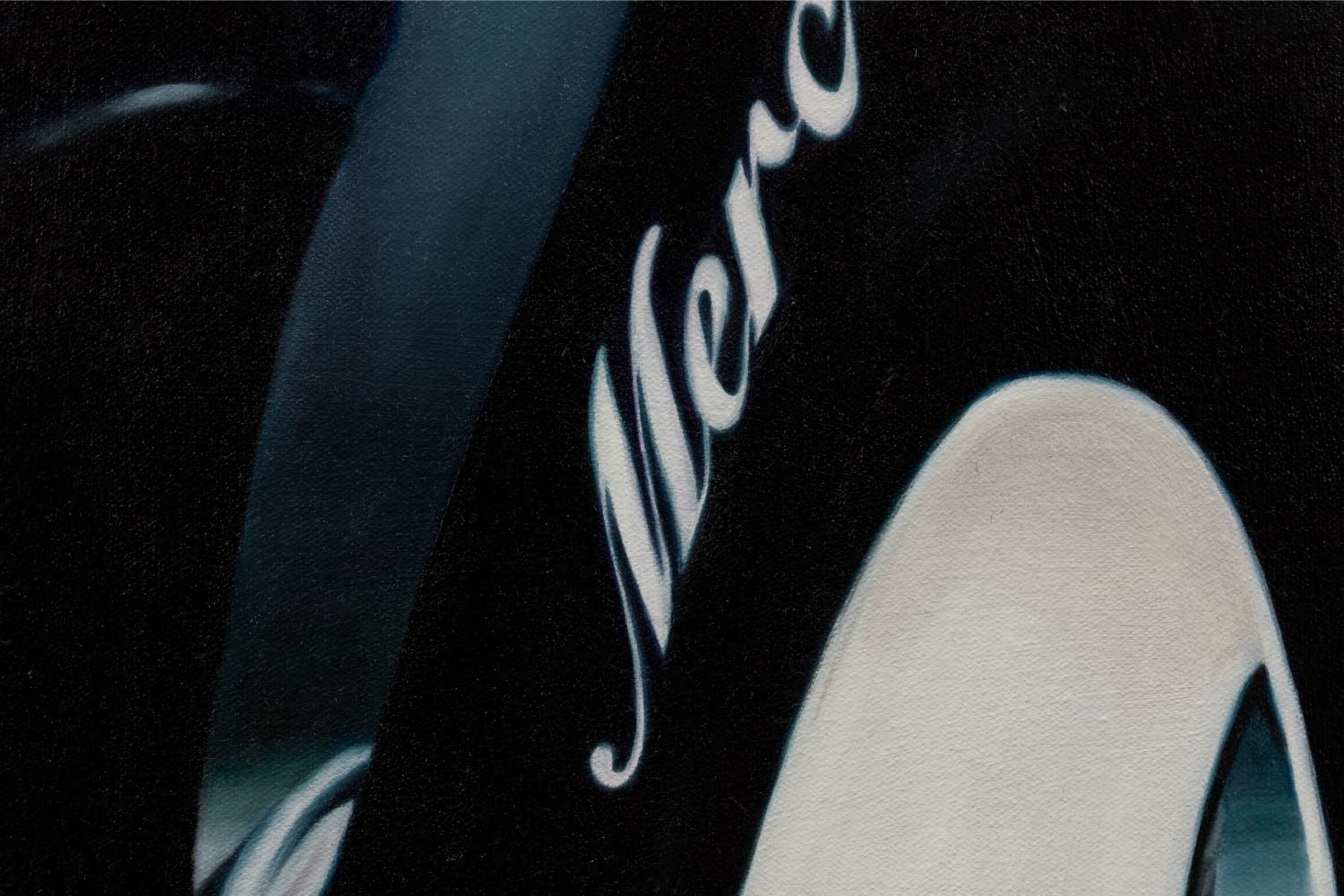

In The New Citroën (1957), Roland Barthes wrote, “Cars today are almost the exact equivalent of the great Gothic cathedrals” – conceived by unknown artists, worshipped by all. He describes the new model (DS 19) with caressing language: its streamlining, dove-tailing, and unbroken metal surround. Looking at Sarkez’s work G-class Dancing with the Shah (2024), I’m reminded of this postmodern dissection. A pair of nine-inch platform pumps (they resemble the height of a Pleaser, a shoe characteristically worn by sex workers and dancers) are embossed with the Mercedes logo. G-Class Dancing could be painted from a stock image. It contains a pull focus of generic content: the kind you’d see on the web page of someone who loves cars and women. Mercedes-Benz G-Class is the categorical term for the G-Wagon, built on the suggestion of the Shah of Iran, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, in 1979. G-Class Dancing captures the camp theatricality of driving an object whose dual purpose and connotative meaning are, for lack of better words, glam-militant. Like the DS 19, the G-wagon became a symbol of new power and money in Iran. G-Class Dancing is a visual essay that, as Barthes writes, discusses how an object becomes “totally prostituted.”

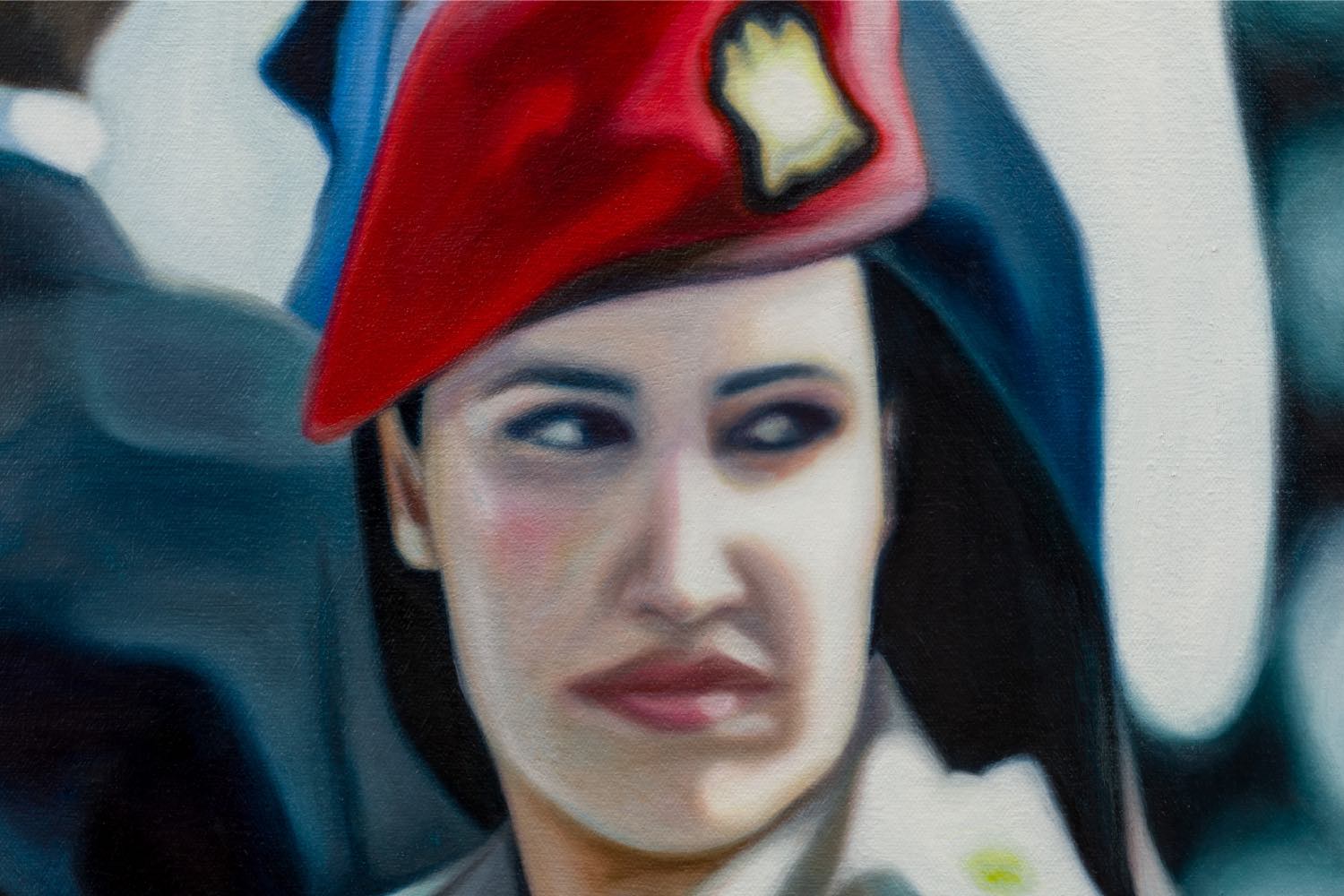

Works like First Lady (2024) perform a similar commentary on the aesthetics of prestige and power. Here Sarkez collages the image of one of Libyan general Muammar Gaddafi’s Amazonian guards in her characteristic semiotic style. The text “First Lady” references the visual format of “skin whitening” soap packaging, an item found in Middle Eastern beauty stores. An image of one of Gaddafi’s Amazonian guards, an all-female group of bodyguards who often appeared in full-glam in the background of press shots, is painted above the label. The coloring of the label imitates the khaki-green of the women’s uniform; a technique Sarkez uses in every work is to color-pick a shade and mix it throughout the painting, resulting in an effect similar to a digital filter.

“White-Knuckle” is full of transformations of the everyday into potent political symbols. In the installations Heart Notes No. 1 and Heart Notes No. 2 (both works 2024) the artist presents rows of scented oil bottles, imitating those found in her local Middle Eastern perfume shops. Their careful labels are irreverent, humorous, and highly specific to the coalescing of Middle Eastern and Western pop culture: “Zayn Malik,” “White Woman Dancing,” “Habibi,” “Hussein,” “American Dream,” and “Sexy Girl.” This sentiment is also seen in The Real Superhero Key (2024), in which a cropped image of a set of keys features the head of an American Eagle, hung adjacent to (C)OEXIST (2024), depicting a Honda motorbike emblazoned with the symbol of the Turkish flag.