The sunsets of Santorini are famous. The crescent-shaped Mediterranean island, sculpted by volcanic eruptions, faces westward and slopes toward the sea like a colossal amphitheater. At sea level, far below the mostly barren landscape dotted with caper shrubs, cruise ships anchor, white and ghostly at dusk. As the mist near the horizon fades into orange, pink, and crimson, sailboats set out from the port of Fira to get the best view of the spectacle.

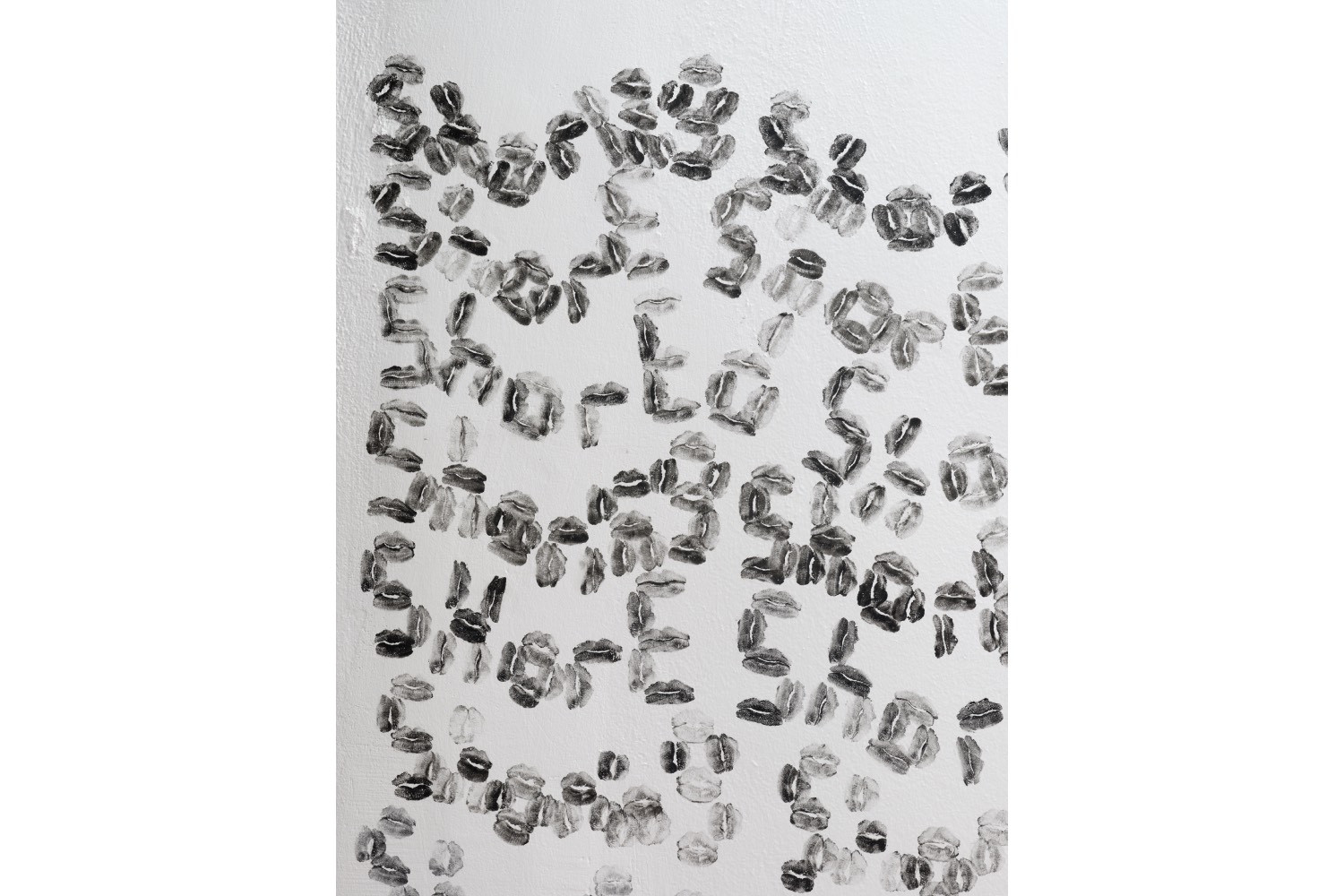

Hidden among the houses that line a bustling thoroughfare is the entrance to Santozeum, a private foundation run by Ileana Nomikos. Here, the exhibition “Weather or Not” opened one night in late August. As the room filled with people, after sunset, artist Michael Dean took to the terrace, exclaiming, “Shored, shores, shore.” His voice drifted into the night over the bay. The performance referenced his mural in one of the spaces at the foundation, a work in which, using his lips and black paint, he spelled the same words over and over again in different variations –– like a rising tide shaped by kisses. When the artist arrived a week earlier, he had no plan for a piece, but his stay led to its creation.

“There are moments when I ask myself what is so intriguing about this place,” Fabian Schöneich tells me two weeks later on the phone. The Berlin-based curator has been working with the foundation for about two years. “And then it happens, for example, that Michael makes his wall work and raves about the lightness of being here. It is simply a space where an artist spends time, and that is incredibly beautiful.”

Not all of the artists in the show made their work in situ. There are the small, tender landscape paintings by Kazuyuki Takezaki, who passed away earlier this year, depicting the mountains in Marugame, Kagawa Prefecture, Japan. These ranges protect the small town from fog and heavy rain. Another artist, Jota Mombaça, presented the video piece until the last morning (2023), commissioned by CCA, the institution that Schöneich runs in Berlin. The unsettling film explores the impact of climate change on sweet-water mangrove forests. Cory Arcangel’s sound work, currentmood (2016), booms through the entrance hall of the former residential building. While Arcangel’s piece primarily investigates club music — white noise set against the unrelenting rhythm of a muted Roland TR-909 drum machine — in this context, above the sea, it also recalls the cadence of waves during a storm. Choosing weather as a theme feels fitting for an island exposed to wind, sun, and sea, where nature’s harsh beauty depends on the surrounding conditions.

“The exhibition ‘Weather or Not,’” says Schöneich, “was an opportunity to show works that are relatively easy to transport.” While the pieces have no direct connection to Santorini, their themes, such as weather, feel especially relevant to this location, which is exposed to the looming effects of climate change, and where cruise ships aggravate it.

A little down the road from the space, a stenciled graffito on a particleboard blocking an entrance reads: “Enjoy your holiday at Europe’s biggest migrant cemetery.” The tourists, disembarking from the cruise ships and flooding the narrow streets lined with white-and-blue buildings, souvenir shops, and restaurants, seem oblivious to it. The juxtaposition of brutally different realities in the same place is jarring.

A term has been haunting art criticism lately: resort. The word refers not just to physical places of recreation, entertainment, and accommodation, but also to something more intangible – the symptom and symbol of a fundamental change in economic and social structures. Critic Isabelle Graw recently addressed this concept in her magazine Texte zur Kunst. According to Graw, speculation, digital economy, and high real estate prices have contributed to a situation where the art world is losing its autonomy to profit-driven interests. The resort, she argues, abstracts artistic production, and that phenomenon is underpinned by a paradigm shift in which artistic production is valued by quantity — prices, measurable attention on social media — and less by judgments reached communally, by way of critics, curators, and other traditional gatekeepers.

In the physical world, this phenomenon manifests in the rise of art-world resorts. One can experience art in places like Provence, France, where you can sip cocktails and dine at a Rirkrit Tiravanija-designed restaurant at the Luma Foundation in Arles. And there are more inaccessible resorts that are tied to — or run by — commercial galleries and private collections. Graw sees these resorts as the antithesis of diversity, creating exclusive, homogenous spaces. She suggests they represent the dialectical counterpart to a more progressive institutional art world – a structural shift that is reshaping the public sphere.

Santozeum, is privately funded and close to mass tourism, but it manages to carve its own distinct space, and the exhibitions are open to everyone. It ticks many boxes of the resort, yet at the same time, so much of it eludes a clear-cut branding. It is as if the curation avoids a finite concept. Santozeum provides “a time and space which are not precisely defined,” says Schöneich. He describes it as a space for ephemeral forms.

The foundation is more interested in long-term collaborations with artists than in fleeting exhibitions. At the same time, the institution stands in contrast to its immediate environment. “The island struggles with mass tourism and the giant ships,” Schöneich explains. The local economy relies on what is fundamentally destructive to its base. Santozeum provides a counterpoint to commerce by showing ephemeral art forms. Still, art institutions tend to not solve economic and ecological conundrums. “Perhaps we criticize what this island is,” Schöneich adds, “but we also propose something. I like this task and the question: What to do with a place like this? At the same time I’ve always been very critical of setting up a summer resort art location.”

Maybe this is where Santozeum diverges from the resort model. While resorts are disconnected from the process of artistic production, Santozeum aims to be a respite for artists. Previous artists-in-residence have left behind works; Raphael Hefti created a colorful floor painting on the institution’s terrace; Megan Dominescu wove tapestry-like knitted pieces; and Leon Pozniakow designed a ceramic column, which playfully draws on classical imagery, in collaboration with local ceramicists. When I ask Schöneich if there is a model for the foundation, he compares it to the rehearsal stage of a theater. “It is a space that is not quite public but can be made public. There is a naivety and freedom that doesn’t exist on the actual stage.”