Kim Sowol’s 1925 poem Azaleas is written from a feminine perspective, where the speaker, anticipating her lover’s leaving, plans to scatter azaleas along their path, allowing them to leave her without resistance. Though this may seem irreconcilable with photography’s inherent desire to capture and to keep, in Lotus L. Kang’s first solo exhibition “Azaleas” at Commonwealth and Council, photography and filmmaking are joined together in the spirit of Kim Sowol’s poem.

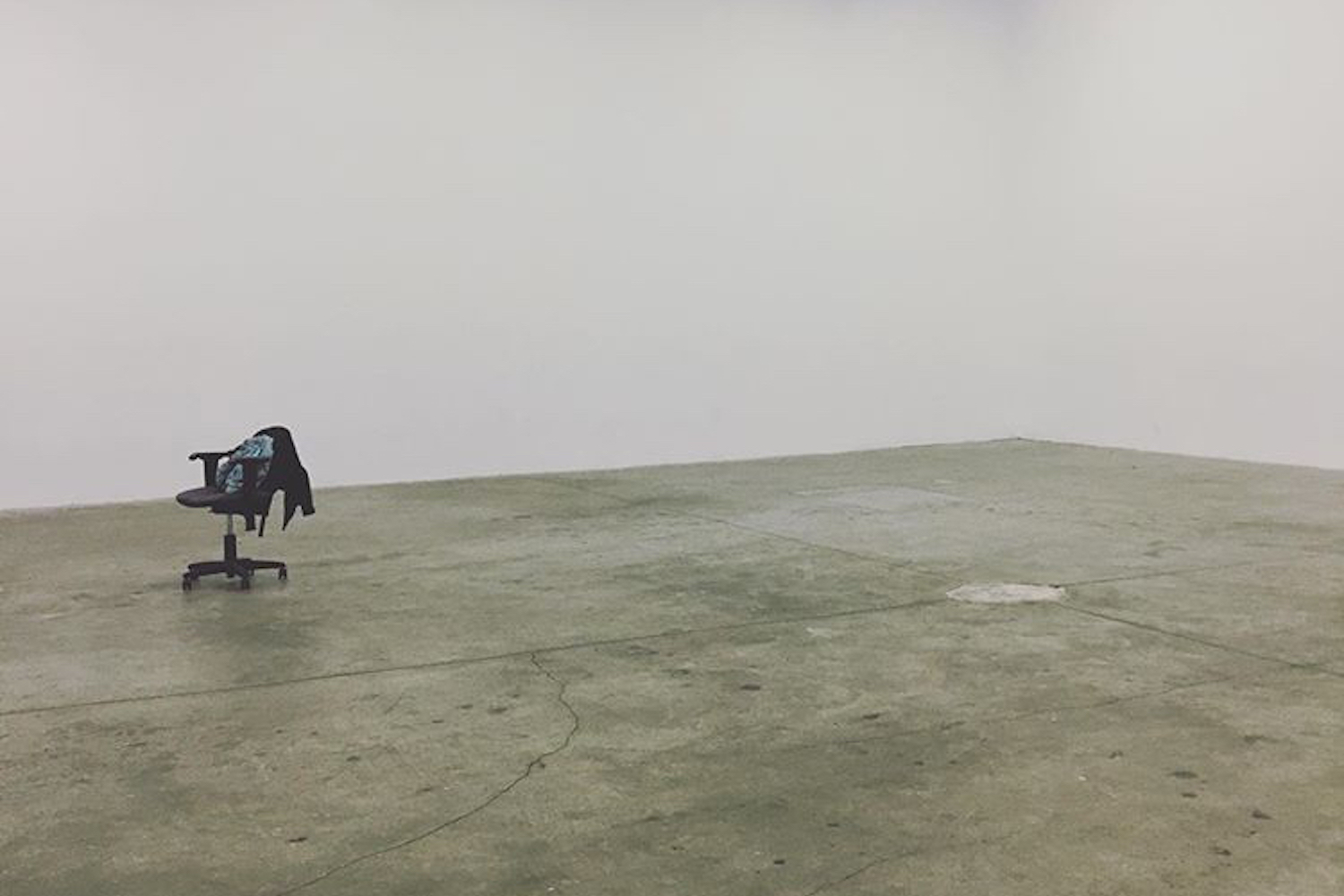

Sheets of unfixed large-format film have become a recognizable element in Lotus L. Kang’s work. Suspended from ceilings or mounted on architectural metal structures, these films are impressionable and therefore fragile. The gradations and markings imprinted on them reflect their mutability and reveal their vulnerability to constant change as they are exposed to light. Inside you there is another you (2024) continues this exploration: in this iteration, two tall cascading films converge to form a bridge between . It is hard to discern the exact number of films withing the draping, but the interplay between them creates an appearance of a gentle tug of war or the movement of string puppets, emphasizing how these films – referred to by the artist as “skins” – represent exteriority. The films themselves are limp and inanimate, yet there is a force acting upon them, so what is seen is its evidence. Much like the title, borrowed from the opening line of Kim Hyesoon’s poem Face (2018), the work draws attention to what is beneath the surface of the visible.

In the second gallery is Kang’s new installation Azaleas (2024), a large kinetic sculpture modeled after an industrial 35 mm film rotary dryer. In Kang’s rendition, 35 mm films are wrapped tautly in striations around the metal frame, moving in a rhythm inspired by the meter of Kim Sowol’s Azaleas (in Korean) and two lines from Kim Hyesoon’s Face (in English). However, even for those intimately familiar with the poems, the meter is not detectable in the movement. While normally this is a mechanism to dry film before developing it, here, the process of the film’s becoming is the film itself, as light installed right behind transforms the sculpture into a projector. Depending on the speed of the rotary and the brightness of the light, what is projected shifts from shadows of forms to actual images in full color. But this is not a film contained in a screen — being in the room gives the sensation of what being inside a film would feel like if it were to have a body.

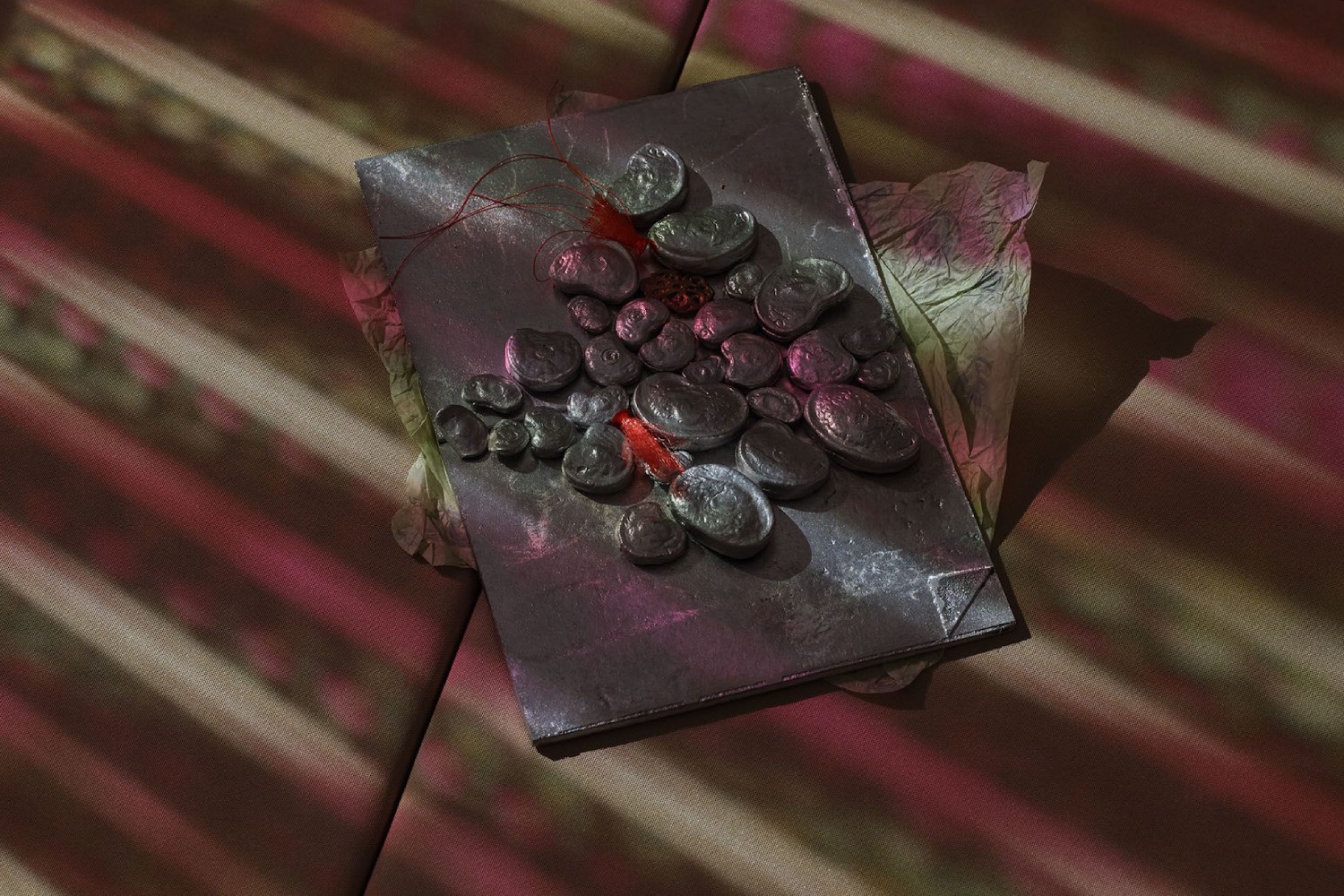

Both the large-format film works as well as the 35 mm film rotary dryer are situated within a larger environment created by Kang, comprising a constellation of objects such as cast aluminum and bronze, tatami mats, soju bottles, a plastic bag, wrapped bundle of pears. While these objects may seem the most tangible in contrast to the ephemeral films, they function as shadows and signifiers – like recalling only the first letter of a forgotten name, or remembering the scent or texture of an experience that can no longer be fully articulated. Kim Sowol only published one collection of poetry and died of suicide, penniless and unknown. Yet, if there is one poet that everyone, even diasporic Koreans with no background in Korean poetry and literature may know of, is Kim Sowol. Kang’s choice to think through Kim’s poem may seem an “obvious” choice, but it prompts reflection on what obviousness means for diasporic Koreans. In my own diasporic life, recounting memories that are so fragmented that I feel ashamed if they even merit as memories, my personhood is muddled and seems inferior to someone who has a command over their history and language. But set within Koreatown of Los Angeles where generations of Korean Americans have made their home, I am reminded, this too, is the history of our people and the inheritance of the colonial imperialist legacy that needs accounting.

What looms largest in Kang’s work is the presence of film and its inherent connection to the inevitability of loss. Yet, alongside this acknowledgement of impermanence, there is a persistence towards the belief to remember, and the possibility to hold onto. Therefore, even as Kim Sowol’s poem may appear resigned to loss, this interpretation holds only if one assumes loss to be a negation of having. But for Kang, as it was for Kim, loss is not nothing – it is in itself an event, it is in itself an experience.