In 1985, Grace Glueck wrote of the New York exhibition “Robert Smithson: The Early Work: 1959–1962” — which was the first time the artist’s works on paper had been seen1 — that its contents came “as a bit of a shock.” Without any doubt, visitors to the new show at Marian Goodman in Paris who are unfamiliar with those ensembles, or with the rather lurid porno-erotic pop works now being brought out of the archives, will feel a similar sense of shock. The works on paper mark a moment when Smithson’s oeuvre was in transition, breaking with his first body of pictorial works — which were close to abstract expressionism — yet still anticipating his minimalist and conceptual work.

In 2020–21, another exhibition at the gallery, “Primordial Beginnings,” brought together an ensemble of collages and graphic works from the 1960s that explored Smithson’s geological, anthropic, and prehistoric tropism.

The more raunchy work was inspired by New York’s Beat and underground culture, and nourished by Smithson’s heterogeneous reading. Previously little explored, its display in “Mundus Subterraneus – Early Works,” co-curated by Lisa Le Feuvre, director of the Holt/Smithson Foundation, and art historian Adrian Rifkin, helps take our understanding of the oeuvre one step further. And if, at first glance, its presentation alongside three other pictorial ensembles gives a feeling of heterogeneity, it does in fact allow us to appreciate the constancy of Smithson’s symbolic and chromatic lexicon and the gradual reversal of his work from a Christic iconology, which corresponds to the intense personal crisis he was going through in 1961, to an erotico-pop register, which forms a kind of inverted, secret, or unspoken complement to the geological and stratificational corpus.

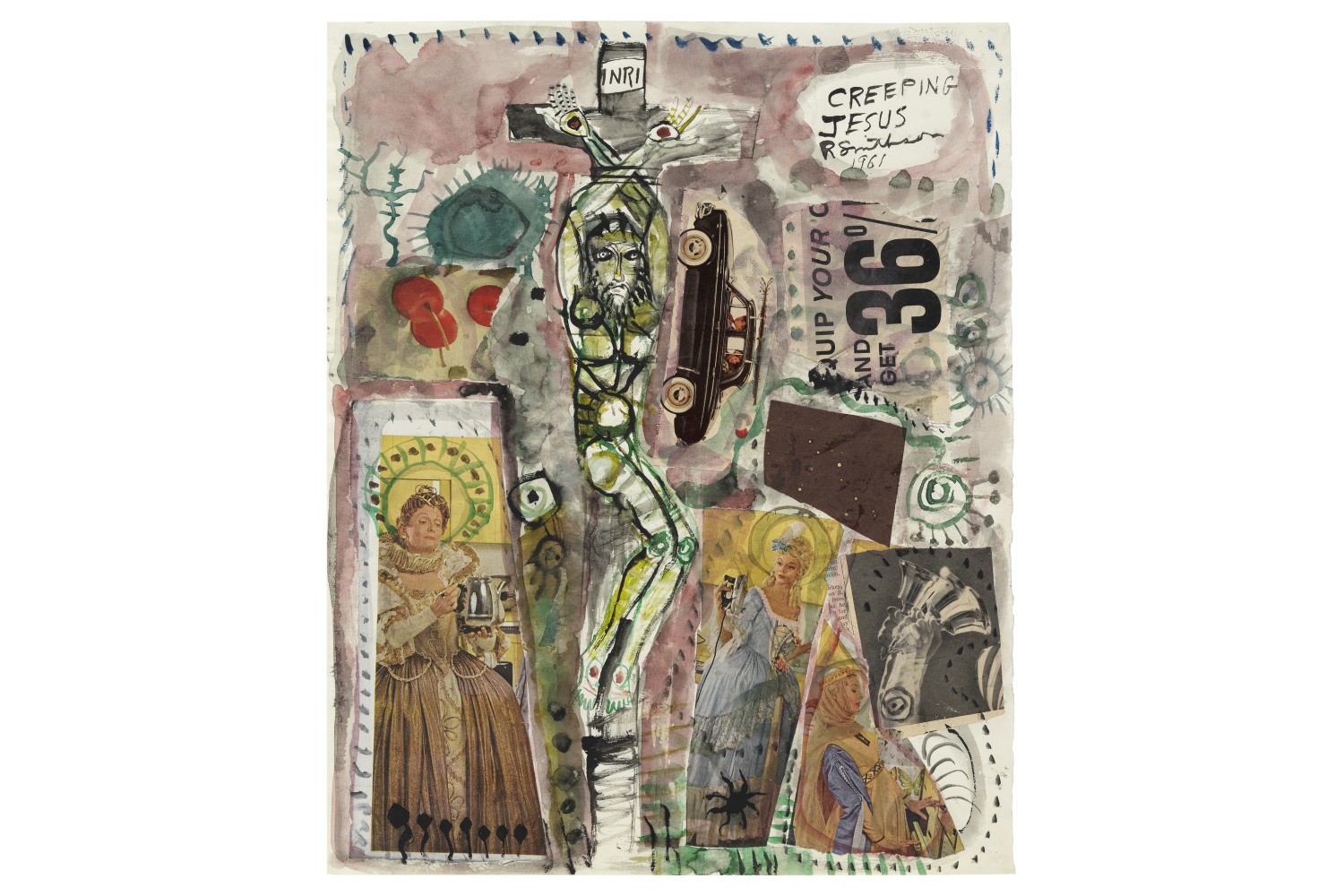

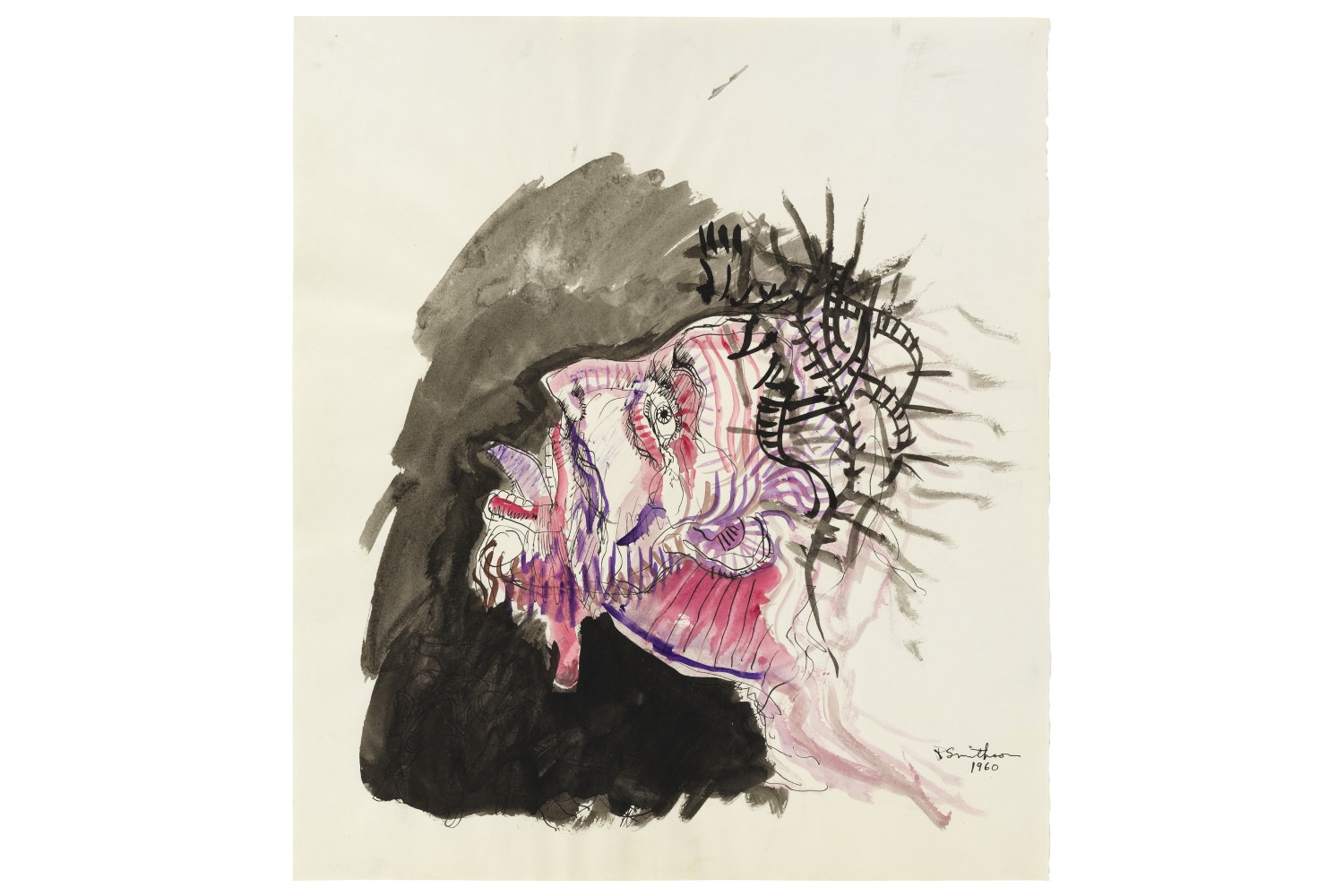

A first ensemble, dated 1960–61, consists of gouaches on paper that perform variations on details of works marked by Christic representations, attesting to Smithson’s intense exploration of religious themes at the time, and the steadfastness of his symbolic and chromatic vocabulary, as well as his interest in showing what is hidden.

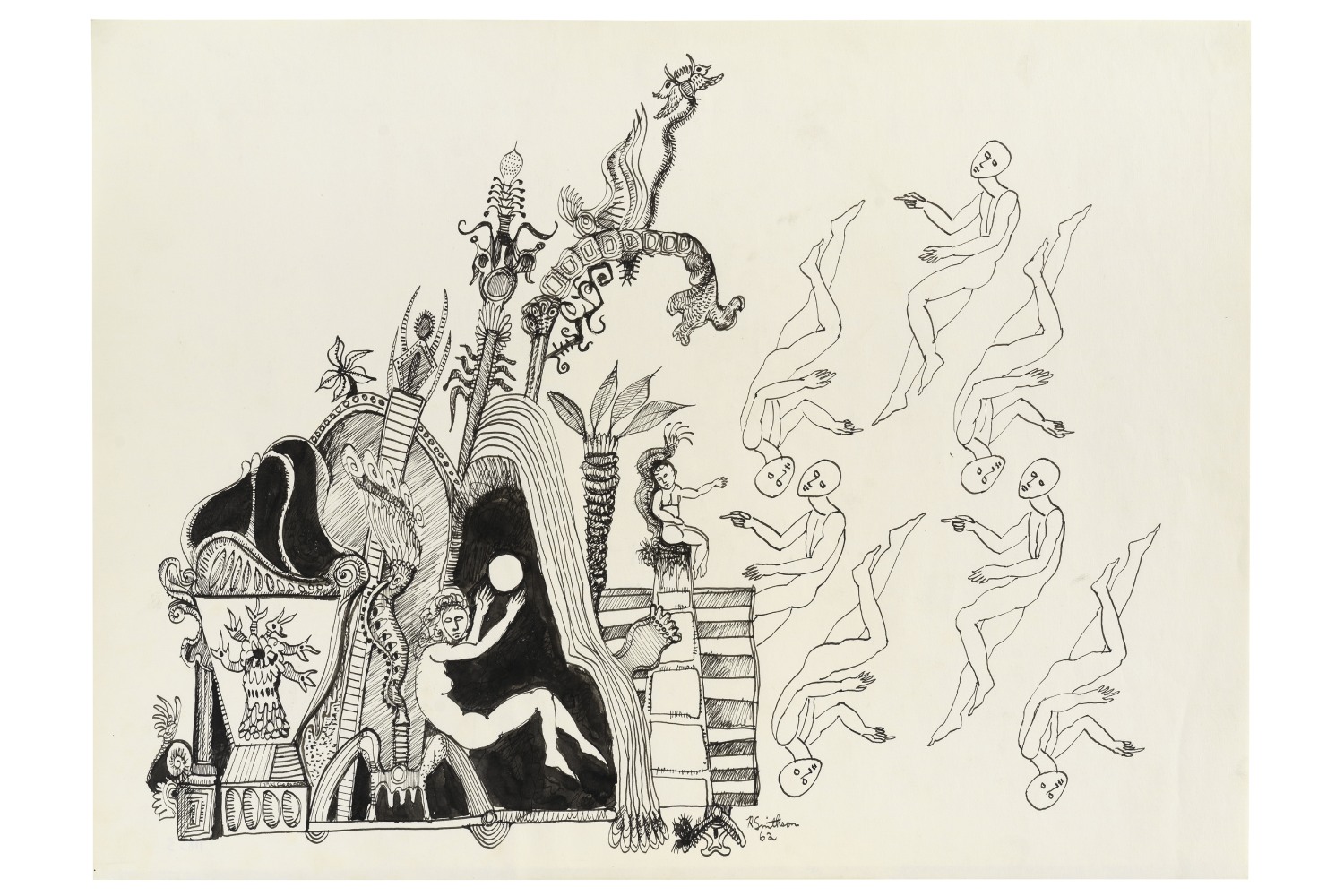

Two later collages, Creeping Jesus (1961), which is well documented, and Untitled (1962), which has probably never been shown, bear witness to the shift from religious iconology to pop themes, with the latter a mix of consumerist imagery — cars, Monopoly banknotes, coupons, a can of milk with a white-and-red label — cut out from magazines along with religious motifs. Untitled depicts, against a sketchy pink/purple wash background, naked figures hurtling toward a limbo represented by a thick layer of pop and floral cut-outs and graphic elements evoking geological works. It seems to be an introduction to this sizeable and never previously exhibited ensemble of works on paper inspired by Beat erotic imagery.

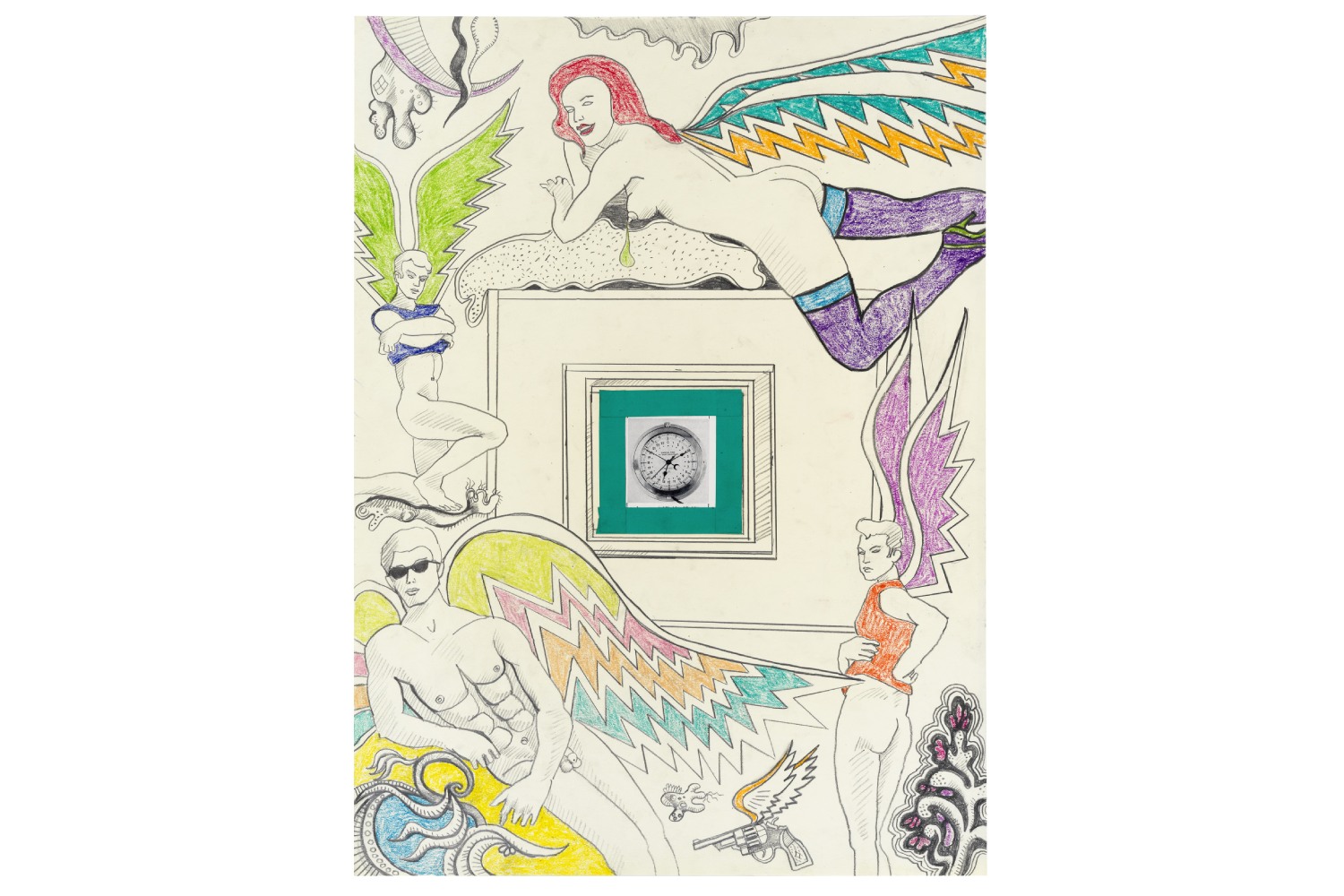

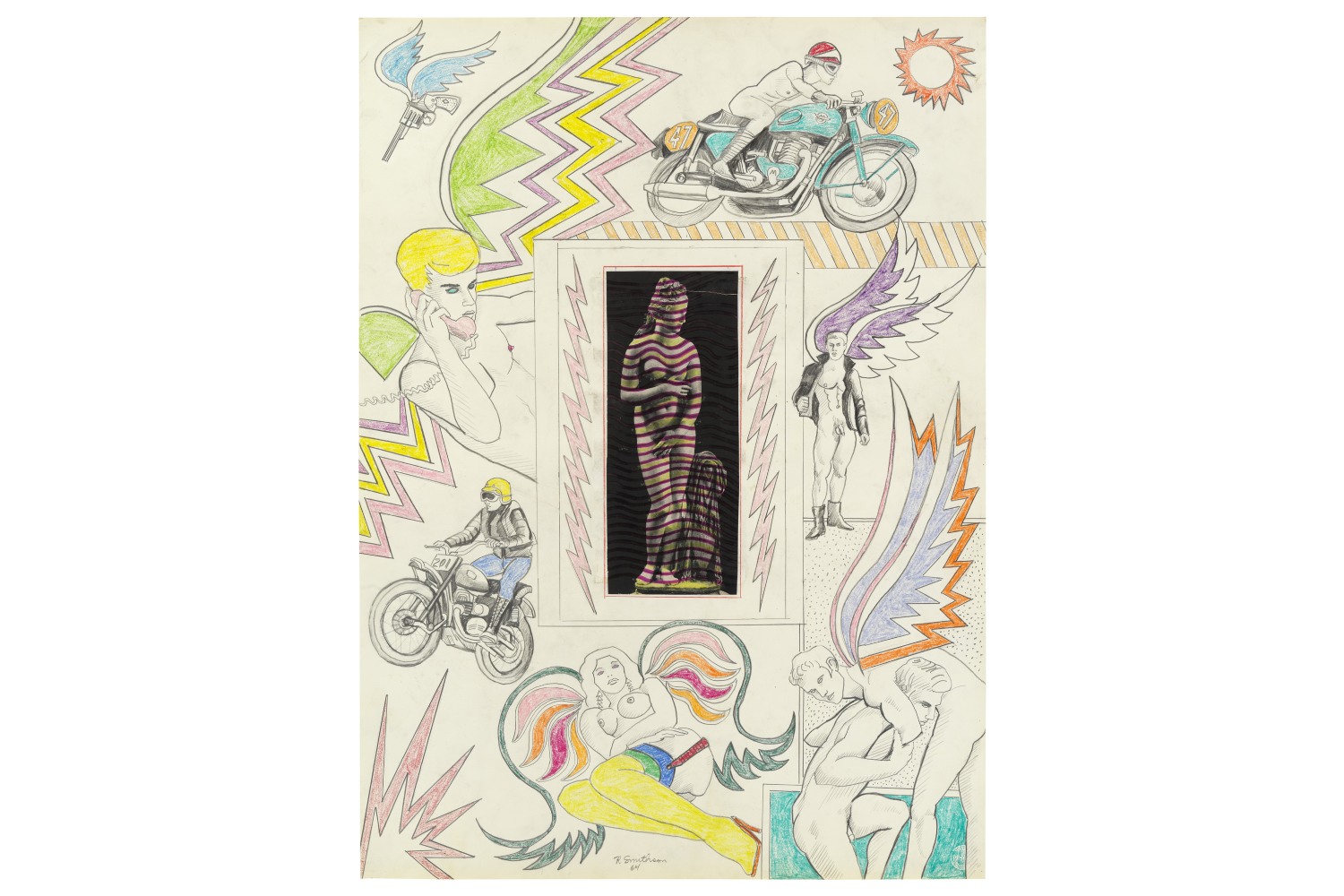

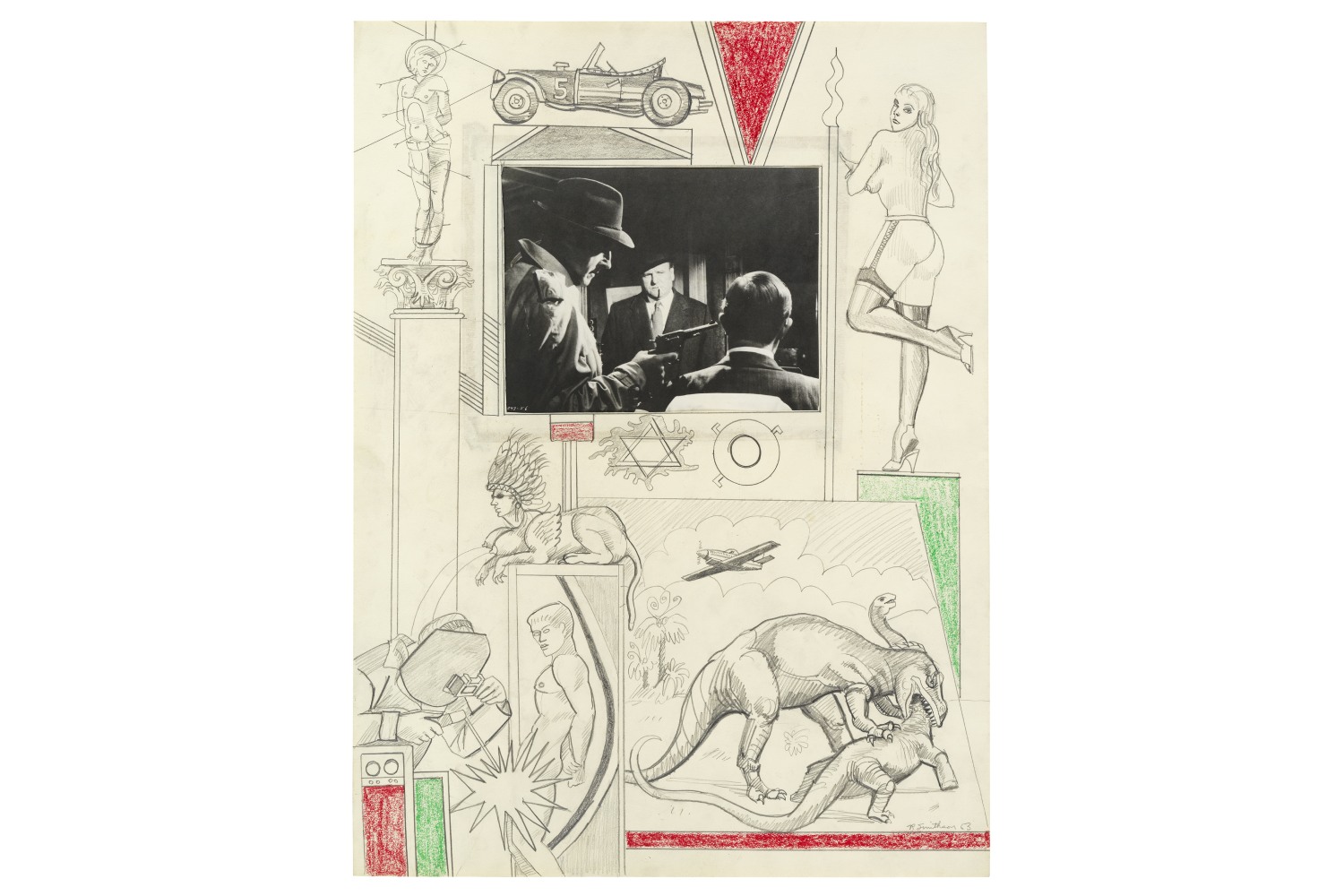

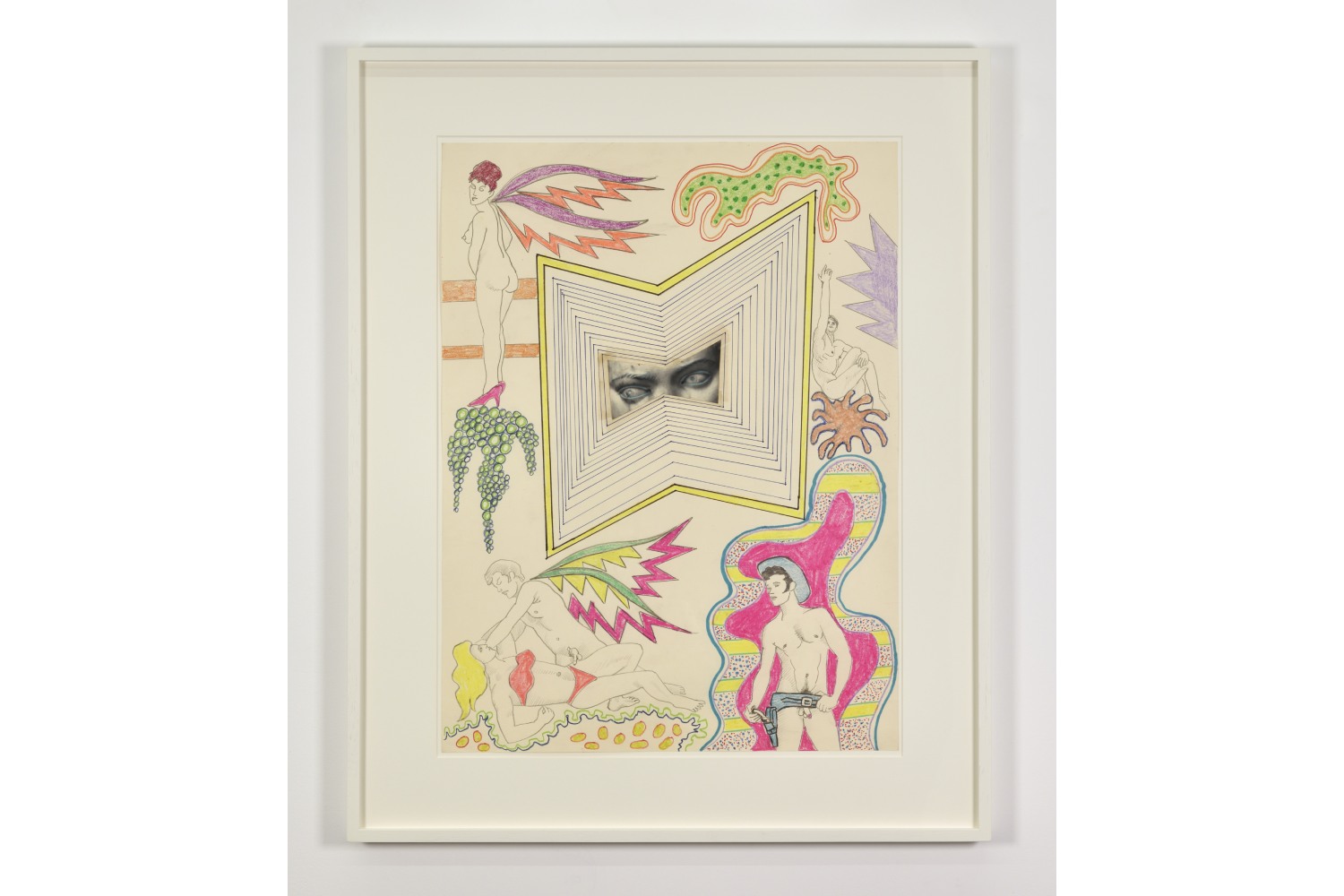

At once pornographic, both gay and heterosexual, borrowed from beefcakes magazines and numerous references to biker aesthetics and comics, this body of works dominates the exhibition, and forms a counterpoint to the better-catalogued works on paper. Winged, naked, or almost-naked figures, coexisting in suggestive poses, bodybuilders or leather-clad men, pinups in suspenders, onanistic or soft-porn scenes that are partially concealed, make up this erotic pantheon, most often in pencil and colored pencil augmented with collages, taking the form of more or less identifiable vignettes dividing the image into frames or dials –– a structure that Smithson seems to have drawn direct inspiration from in his later pop works, whose “hidden” dimension he often evoked2. Motorbikes, cars, revolvers, turbine engines, sidereal clocks — all join this pantheon, where they occupy an essential position, evoking both the pop and biker themes and the Duchampian theme of the bachelor machine, which would be present in later three-dimensional Smithson works featuring images of pinups, such as The Machine Taking a Wife (1964).

One of the most emblematic works in this series, Untitled (Second-Stage Injector) (1963), has an affixed-with-thick-red-tape image of an engine component at its center, bearing the eponymous inscription and surrounded by a circle. In a vignette, two young, naked, winged men are standing around a convertible they are filling at the pump. One of them holds the hose, thus turning the word “gas” on the petrol pump into “gay” as his arm cuts across the S to make it read as a Y. Dressed in yellow, the driver is watching the second naked man, who is filling the car’s tank. In another vignette, a gender-fluid figure with prominent breasts and male genitalia protuberantly displayed, like an Odalisque facing the viewer, reclines on pink stripes. To his/her right, a hermaphroditic enwrapped-by-a-green-snake figure, wearing Pan’s ears and bringing to mind a similar character from Michelangelo’s Last Judgment (1536–41), peers below a winged female figure, her sex concealed by a red heart, her hands and feet darting lightning bolts, herself below a blue bolt of lightning — a recurring figure in Smithsonian iconography that is found at the center of all his three-dimensional pop works.

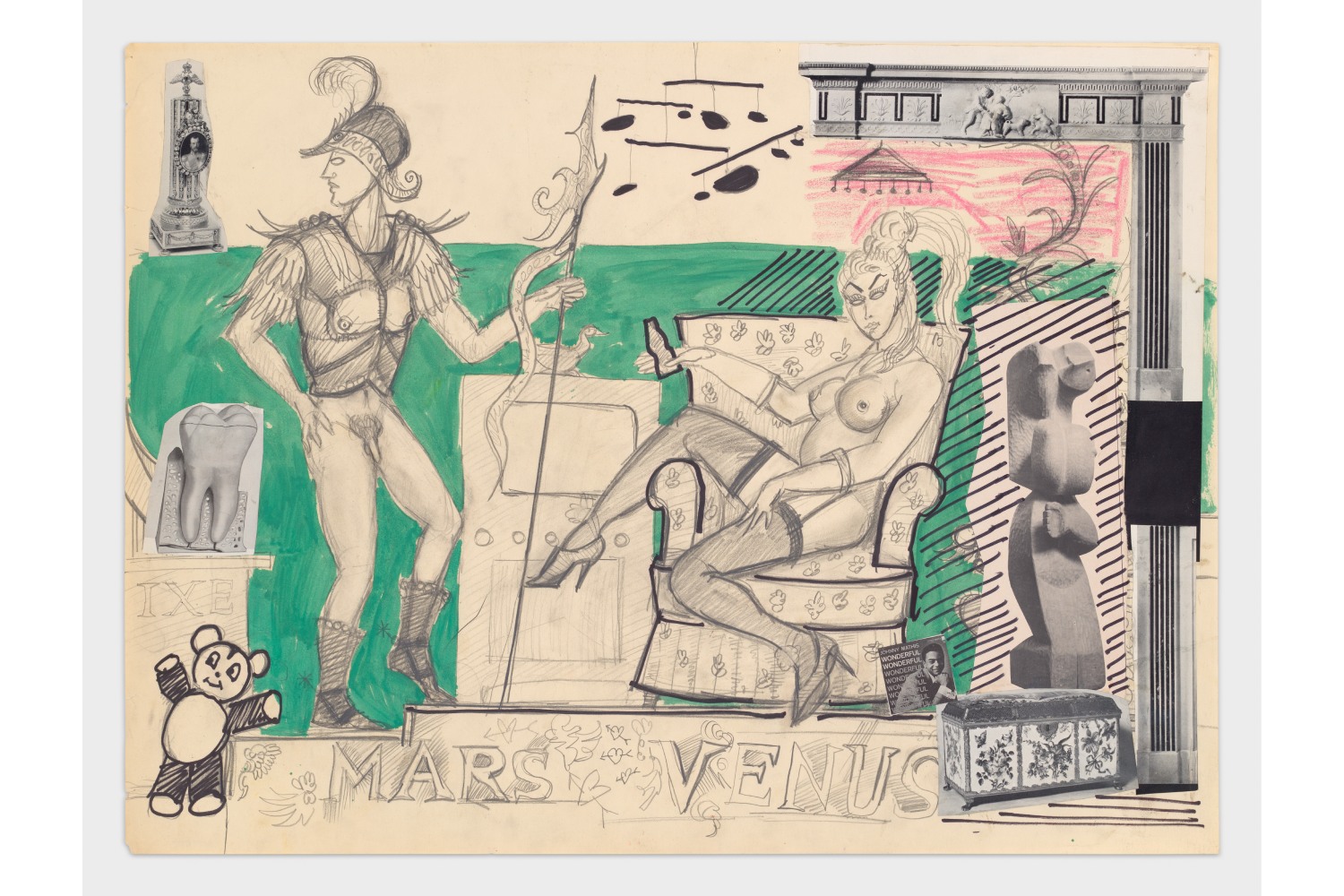

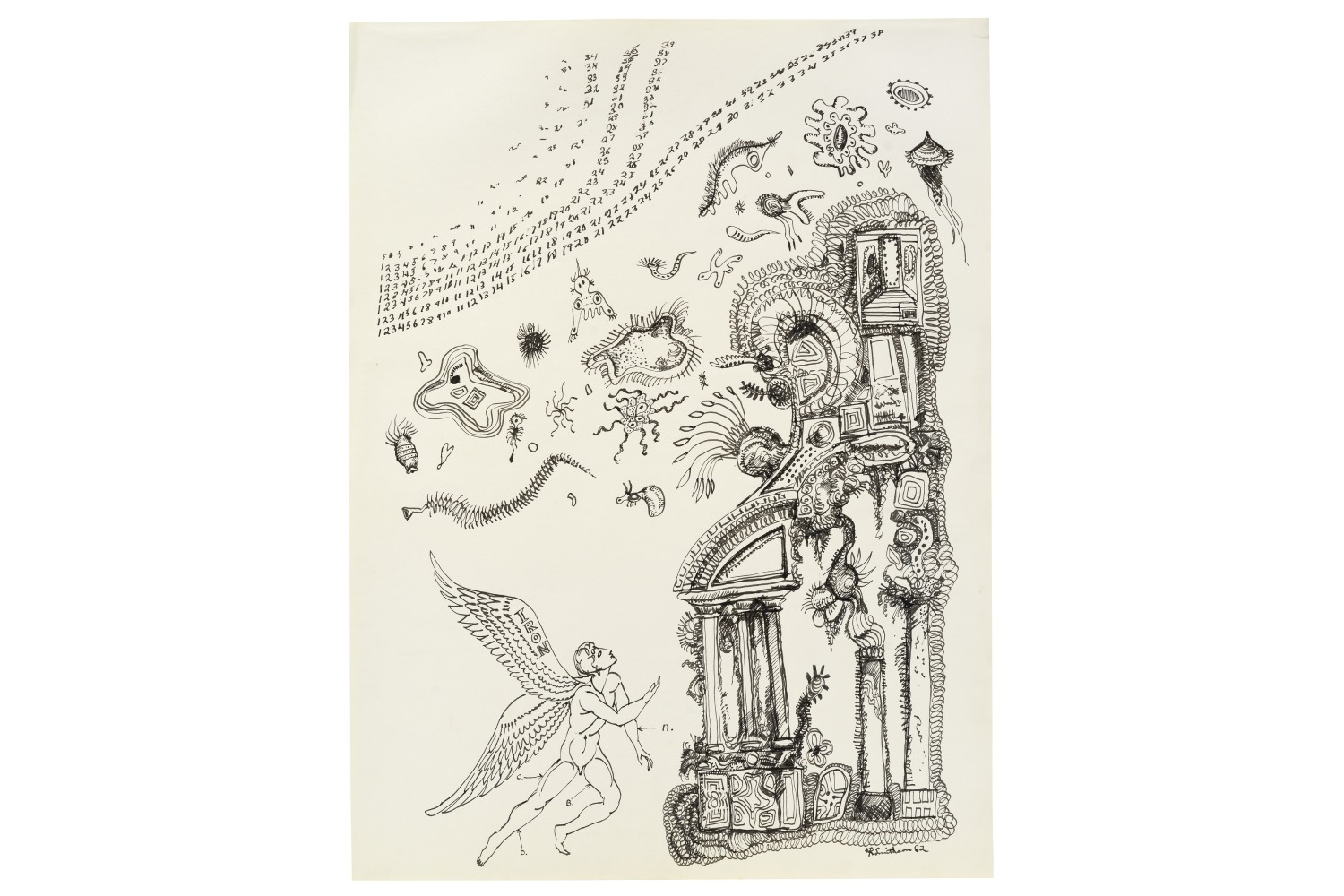

Untitled (1963), with the image of a sidereal time-measuring instrument at its center evoking Chronos, a Greek god considered to be Orphic, seems to be the reversal of the pop-flowered Untitled (1962). Similarly dominated by a woman figure with broad wings, this time the angel hovering above the clouds is replaced by a pinup drawn in pencil and colored pencil, with purple stockings and green stiletto heels, red hair, and lips. Nude, straddling the central frame, she seems to be resting on a cloud of an unidentifiable liquid, while the male figures, all drawn from gay erotic imagery, repeat one by one the positions of the angelic figures in Untitled (1962). Motifs of pink and black roots reiterated in the geological works leave little doubt as to the hidden dimension, buried in limbo, of this work and therefore this series, which the artist kept hidden away. This leads us to notice that the Untitled (1962) falling winged figures themselves seem to be taken from a series of graphic works in black ink on paper dating from 1962, also presented here, which are augmented with various scriptural elements and with the recurrent figure of the ruined Doric temple — a motif that irresistibly brings to mind Didier Eribon’s writings on the place of the Doric in then-forced-to-be-dissimulated gay imagery beginning in the nineteenth century3, and which is also reflected in Smithson’s Mars-Venus (1961–63).

Untitled (1964), which has the same chromatic tones, seems to revisit the traumatic episode in which Smithson learned over the telephone of the death of his best friend, who had become a Hells Angel and died on his motorbike during a chase with the police. This figure of the Angel of Hell, taking the term quite literally, seems to have inspired the series: it inverts the representation of angelism, therefore exploring the notion of the fall both in the Dantean sense and as an archetype following representations of puritanical 1960s America.

While some collages remain within gay contemporary erotic iconology — one of them lines up a set of vignettes depicting male organs in black and white, while another, dating from 1964, shows two vignettes of naked men cut out of bodybuilding men cut out of beefcakes magazines, in poses surrounded by a staircase, which will become an omnipresent motif in Smithson’s later work4 — others also borrow in a more softcore way from heterosexual and homosexual pornographic imagery. Leather-clad men, bikers, revolvers, and evocative book covers embody a fetishist representation that was highly transgressive in the puritanical America of the 1960s.

This erotico-archetypal body of work is the missing link in our understanding of Smithson’s oeuvre and thought. Immersed in the New York underground, he discovered Freud’s writings in 1957 and read them avidly, following that with the work of Jung, whose theories never ceased to interest him. The exploration of archetypes, in the Jungian sense of the term, is a constant in Smithson’s work. This series clearly shows that he was exploring the erotic strata of his own unconscious and the archetypes and desires populating it, representing the subterranean, or hidden, foundation of the human psyche through the exploration of his own.