The sibilance of camera shutters fills the gallery for fifteen seconds every forty. This hiss was drowned out by the din of the crowd on opening night. When I revisit Raphaela Vogel’s “In the Expanded Penalty Box: Did You Happen to See the Most Beautiful Fox?” alone, however, it feels eerily pronounced, a reminder of the installation’s vigilant eye, its deafening whisper resounding. In 2024, after all, cameras can capture your image with more stealth. These cameras, as can be expected from their hiss, do indeed seize your likeness; then they share it. The installation’s basic concept is an experience of surveillance. Fifteen seconds of snap snap snap in rapid succession, and then a slideshow of the images taken just seconds before is projected on the opposite wall. Visitors hoping for an Instagrammable experience will be frustrated. The angles are unflattering, and the images flash so quickly and sporadically, it’s hard to capture one with your iPhone. I tried.

The activity of surveillance is located inside a hulking fossil of photoimaging equipment curved like a rib cage positioned at the room’s center. Think an airport body scanner but bigger and conjuring 1980s tech from a film like Videodrome. (Even though this scanner, designed for police and insurance investigation, is only about eight or nine years old, there was erroneous lore circulated at the opening that it’s a carcass of a surveillance apparatus from another era retrofitted with more contemporary gear.) Minimal effort has been made to hide any wiring. In fact, there is such a spectacle of wires, I wonder if some of them are even in use. During the opening, a foot’s pull of a cord knocked the projector to the side enough that the wall display was distorted for a few minutes, until Vogel, the artist herself, noticed and repositioned it. The incident made unavoidable that there’s a vulnerability to the set-up, a near spilling of guts.

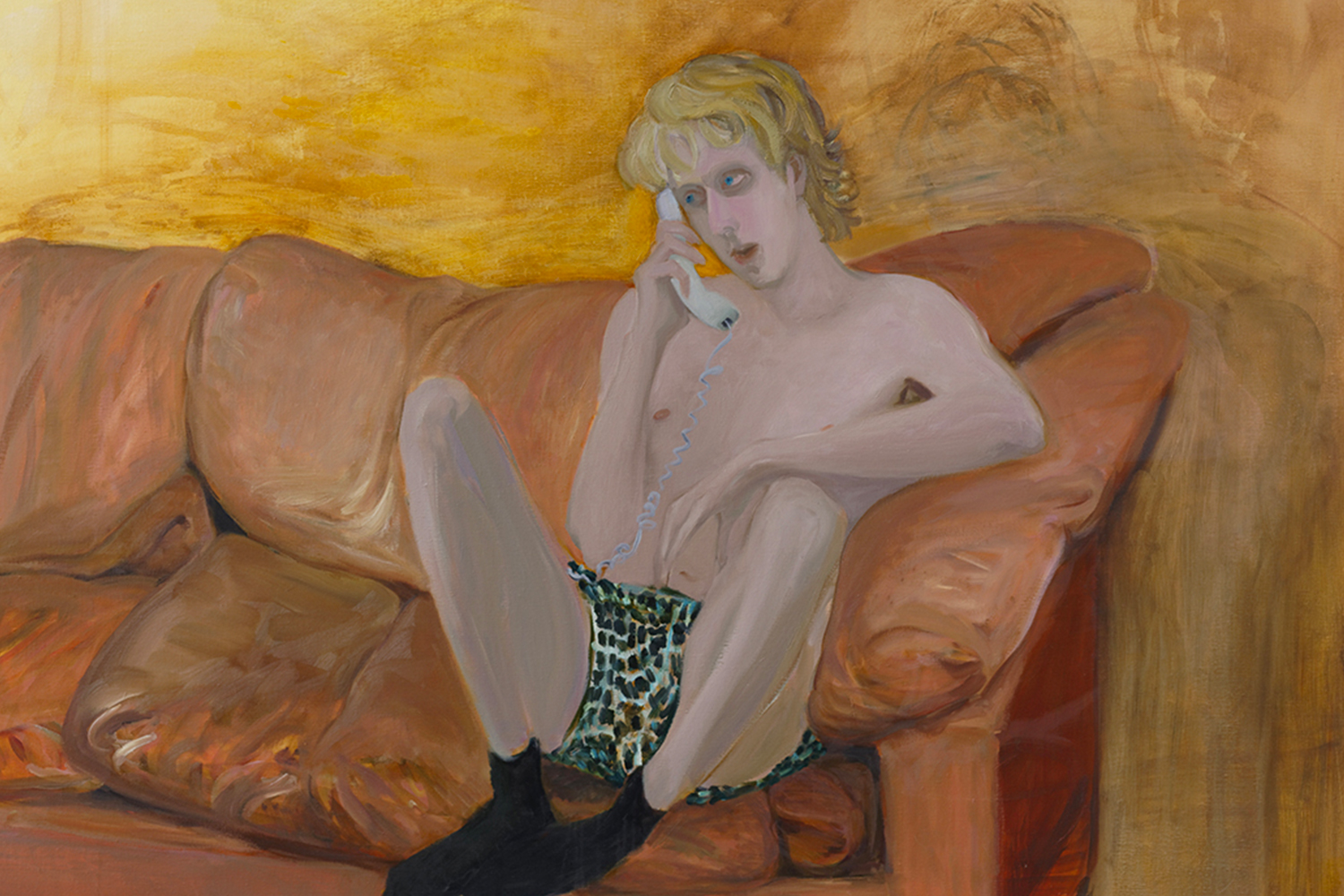

One of three bronze figures (Vogel has titled the series “Unspecial Agents”) is kneeling down holding this projector and another. The second projector points back in the direction of the ribcage-scanner, but up at an inverted pyramid hanging from the ceiling. On a screen stretched across one side of this pyramid a video plays — although it’s not exactly a video; it’s a series of still frames which were also taken inside the apparatus, featuring the artist costumed in a three-faced mask (rubber, Halloween store) and monarch butterfly wings (hand painted, school play). It’s a vignette of grotesque transformation, but the movement direction is childlike and playful. One boot in the air. Two silver lion statuettes in her hands like toys. Together with the title’s callback to Rosalind Krauss’s essay “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” (1979), the pyramid’s shape recalls Krauss’s diagram, outlining the relationship between sculpture, architecture, and landscape. We’ve moved, however, to the penalty box, where contestants are punished for how they play on the field.

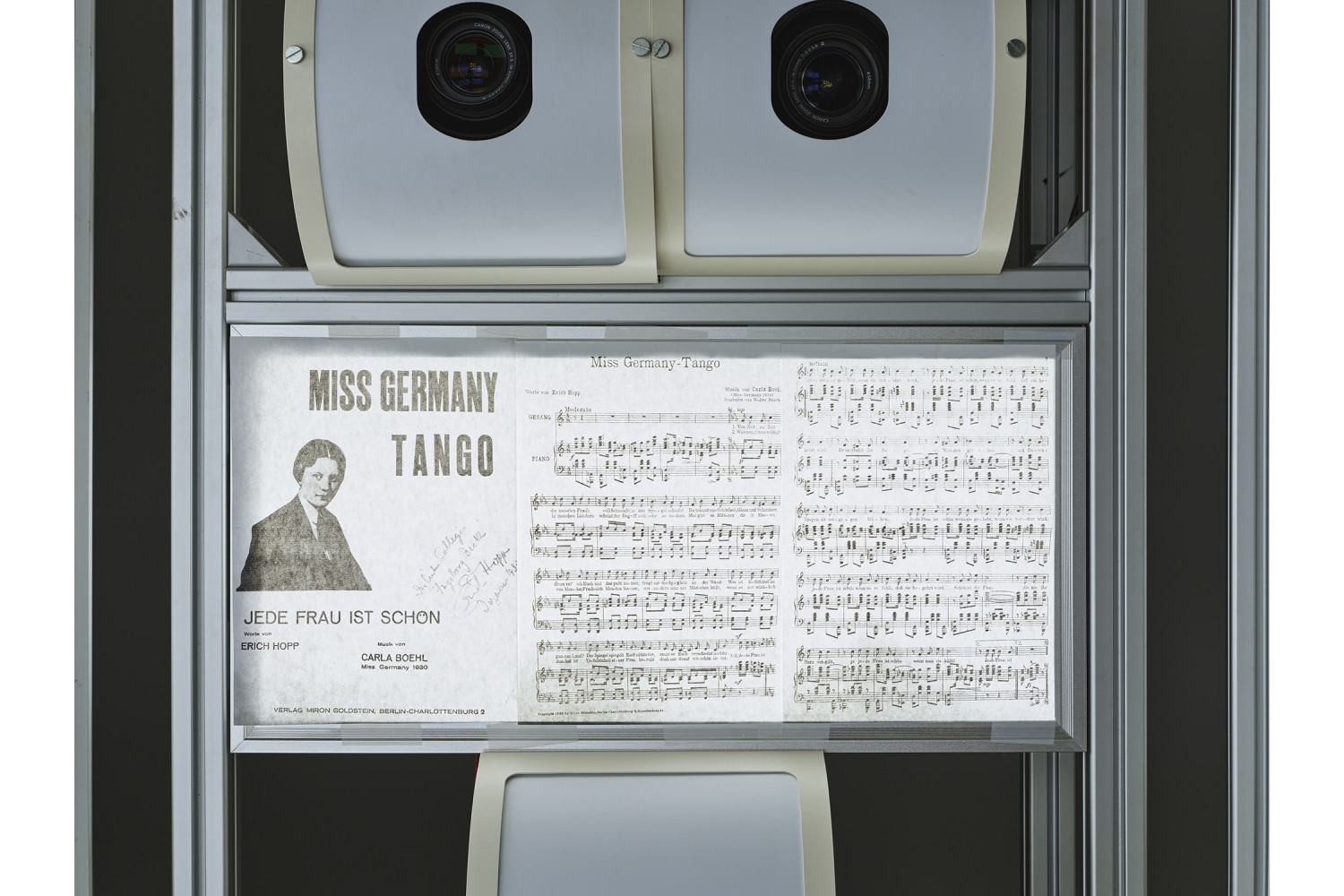

While the shuttering cameras and the projection of the new images they capture is cycling on a forty-second loop, the prerecorded projection of the performance on the inverted pyramid replays every four minutes. There’s a soundtrack repeating also in four-minute intervals, coordinated with the masked performance documentation. This soundtrack consists of two songs: one tango, the other death metal — both have strong rhythmic qualities that dominate the entire gallery room. The tango, which plays for nearly three of the four minutes, was written in 1930 by Jewish-German composer Erich Hopp before he had to go into hiding when the Nazis took power (sheet music for it, titled MISS GERMANY TANGO, is hung on an inside wall of the surveillance apparatus). The metalcore song, titled “All Hail the Dead” (2004), is by a band called the Walls of Jericho — the biblical Jericho is located in the occupied West Bank. This is Vogel’s first major show in the US, and she’s primarily shown in Germany, where authorities have been policing Palestinian solidarity as a hate crime.

Another sculpture in the installation further prompts consideration of the concept of surveillance in relation to remembrance of the Holocaust: a mobile with two hanging skins, each painted with the face of a theorist of contested remembrances. On one side: Jürgen Habermas, who, in the 1980s, argued the Holocaust should not be compared to other genocides, but in the context of a nationalist neoconservative movement trying to purge responsibility. On the other: Achille Mbembe, who later updated the discourse on Holocaust memory to encompass a global anticolonial politic, spanning South Africa’s and Israeli’s apartheid systems. In Vogel’s installation you can never quite get a handle on what picture they have of you, but the rhythm of the oversight beats on.