“Thank you for the tour. I have to say, though, some things weren’t for me . . .” The rest of the group had dispersed. As she moved towards me, twinkling smile, her eyes fixed upon me. She wore a Chanel jacket and sapphire clip-on earrings, her ash blonde bob blow-dried to create thick, sumptuous waves, like the cover star of a 1960s edition of Tatler magazine. I knew it was coming. Risking impertinence, I asked: “I noticed you rolled your eyes. You didn’t like Mandy El-Sayegh’s paintings?” “She had too many positions,” the woman replied abruptly, turning her face away in anger.

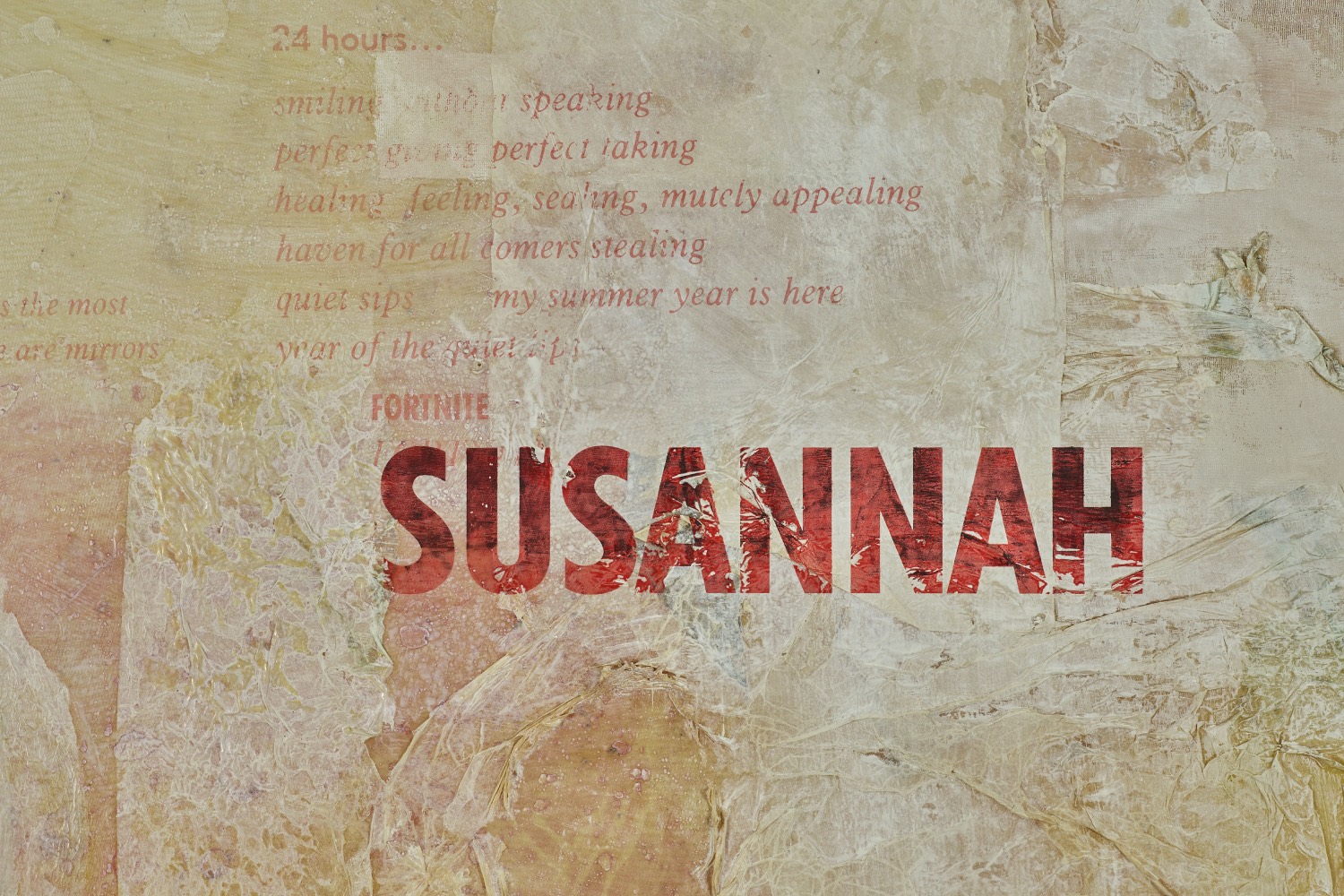

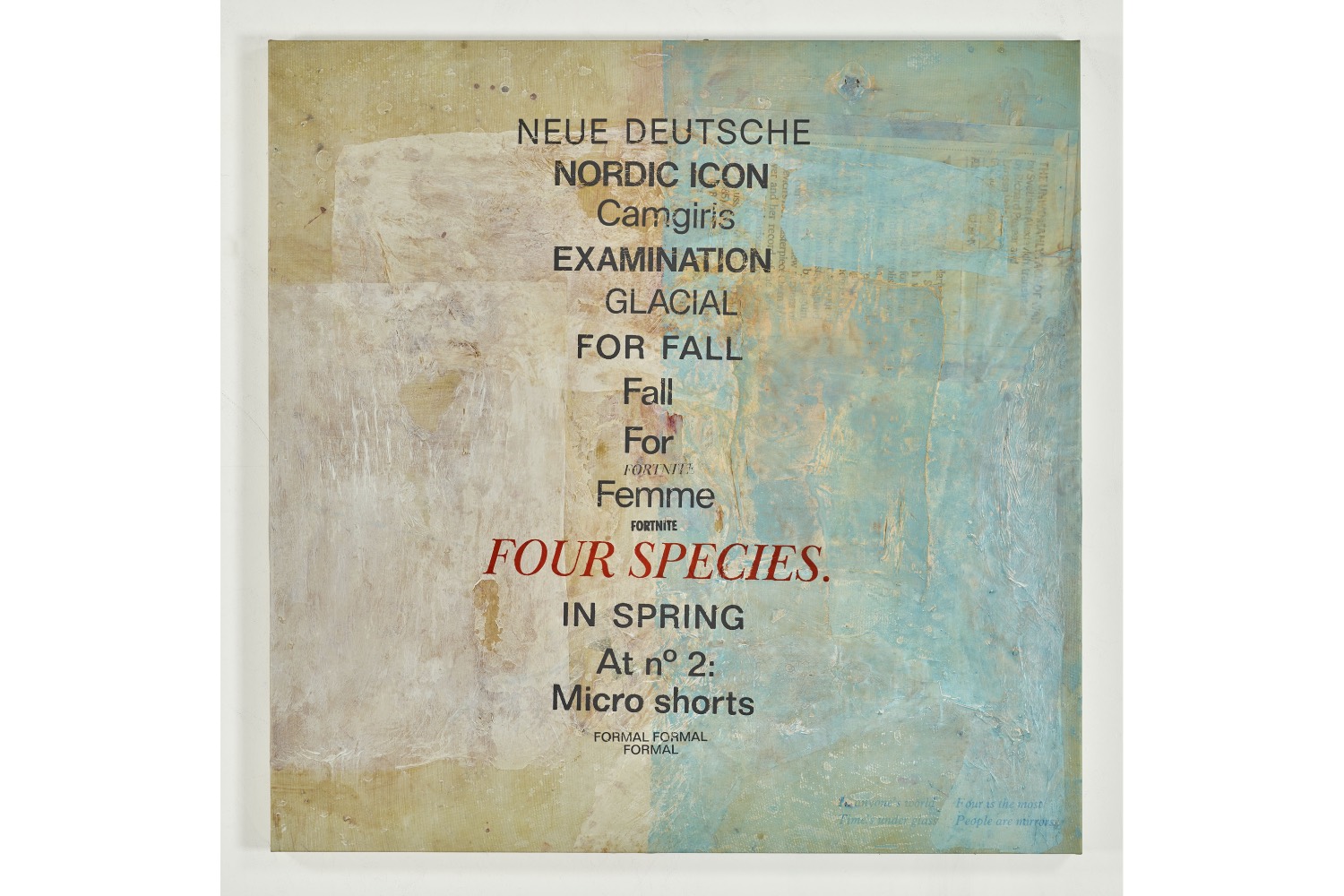

A gallery from Bogotá was showing some works from the artist’s “Search/Operation” series. “Born in Malaysia to a Malaysian Chinese mother and Palestinian father, El-Sayegh makes fleshy-colored collage paintings that lay bare the violence of categorizing bodies and the borders that restrict their movement,” I told my tour groups, paraphrasing a press release. Guides only have a single day to prep our tours. On install day, Tuesday, before the fair opens to the public the next day, we run around trying to catch a word from stressed-out gallerists, really only interested in speaking to potential buyers. “Youʼre from Tours!? Come back later,” they usually say. As I explain to visitors, the artist prints words and phrases across the canvas, appropriating the fonts of glossy fashion magazines. You can see online porn search terms: Ebony, SWALLOWER, Escort, BEURETTE (a pejorative term for an Arab woman). In the middle of each painting, writ large, the code names of Israeli military operations, mainly from the early 2000s, like wounds cut into the canvas: Susannah, Spring of Youth, Summer Rains/Autumn Clouds, Four Species.

“Now, Palestine, there are two sides to the argument, but we don’t have to talk about that . . .” A handsome, middle-aged man suddenly interjected, “Thank you for the amazing tour!” He wore a blue linen suit and pair of white Veja shoes, sun-kissed skin, and slight blotching on the bridge of his nose. Under one arm, he held a brown leather folio, flopping at the corners, seemingly empty. “What do you do for living outside of the fair? Are you an artist? I’m always looking to expand my collection. Who would you say is going to be big in five years?” The woman, I assume his mother, flashed a fierce look at her son, who immediately retreated, wary I imagined she might withdraw her support for his budding art consultancy business. Searching the fair floor, he recognized a passerby and paced off after them down an avenue of booths, no doubt hoping to persuade them to let him buy something.

She looked at me, her face now soft and kind. “Might I offer you some feedback?” Before I could make my excuses, “There was too much politics and sadness in your tour. I want to be uplifted up by art. Art should be beautiful.” She leaned in close. I could smell her heady perfume, feel the warmth of her breath, the champagne from lunch now turned sour. Speaking in a soft, low voice, she offered, “Some friends and I went to the Prado recently, in Spain. We had a wonderful private tour from the curator, who showed us a Goya painting. A group of peasants are caught in a snowstorm on their way back from market.” I recently searched for the painting on Google images and I found The Snowstorm or Winter (1786) by Francisco de Goya y Lucientes. “A work of true beauty. The curator said, ‘If you stop and listen, you can actually hear the sound of the snow blowing across the painting.’” She paused, then raised her hand, as if clasping something delicate between her fingers, and whispered, “If you can’t hear a work of art, if it doesn’t sing to you, it’s not a work of art.” I couldn’t be bothered with it. I was hungry. We agreed to disagree.

At the time, it was only my second year guiding. Now I’ve done seven editions of the fair. As a guide, the guests I tour, mainly rich collectors, they want to feel pity and sympathy, but they want you to relieve them of any guilt or responsibility, the need to actually do anything about it. They want to buy pain, to own it and control it.

On my breaks between tours, I study El-Sayeghʼs paintings. They look like landscapes or bodies. The artist deploys flesh-colored pinks and browns, deep reds like clotting blood, a mark of a crime; azure blue and turquoise, the color of the sky and sea, separated in color fields, setting off a longing for space, the freedom to travel, somehow out of reach, closed off. On the surface on the canvases, El-Sayegh layers newspaper cut-outs, torn scraps of paper, rippled latex that reminds me of blisters that have been saturated by hot bathwater, annotated proofs of a text on psychological theory, a map of sprawling roads and French villages, conjuring the terrior, which has an ungraspable meaning that supposedly can’t be described. It’s a feeling.

The paintings, the printed words, the colors, run out over onto the gallery booth’s thin partition wall, disrupting the boundary between the pictorial surface and the fair’s architecture. What is for sale? Just the canvas? The painting on the wall can’t be detached, nor can it ever be really replicated, at least not exactly the same.

The fair lighting is always blindingly bright. A desert of white. By the end of the week, my eyes dry up and the lids become red and swollen. I have to squint to focus on short distances. I find it hard to hold eye contact with people. I read a quote from the artist: “I always want to eradicate, or mitigate, the starkness of a white space. Bringing that warmth and activity and movement from the studio, where I make the work, into the space that people can feel that activity.”

In the hypercapitalist space of the fair, there are paintings everywhere, tangible commodities, unique, one-of-a-kind objects invested with the artist’s singular touch. Easy to trade, they can be put up on the walls of collectors’ townhouses. All the paintings become indistinguishable, and yet it’s here I encounter an unmistakable pain and fury that can’t be bought or contained, that cannot be denied, that must be spoken.