To delve into Coco Fusco’s practice, it may be better to start at the end. Over the past three decades, the Cuban American artist has forged, through her research, an alternative perspective on sensitive issues surrounding the hierarchization of non-Western culture and the instruments employed in such violence. Her activism during the past fifteen years, focusing on post-revolutionary conditions in Cuba and subsequent censorship by the regime, has erased the boundary that separates art from the world, making this threshold porous and reactive, at the same time generating a play of perspectives between violence and those subjected to it. Using narrative and fictional tools, Fusco has shown how such conditions are mirrored by a subliminal process that propagates supremacist, Western, and often patriarchal information.

The final work featured in “Tomorrow, I will become an Island” — the first major retrospective exhibition dedicated to the artist, curated by Léon Kruijswijk and Anna Gritz at KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin — is a video essay from 2021, recorded in the waters around Hart Island, home to the largest mass grave in the United States, where New York’s unclaimed pandemic’s victims have been buried. The title of the work, Your Eyes Will Be An Empty Word, comes from a Cesare Pavese poem discovered after his death, “Verrà la morte e avrà i tuoi occhi” (1950).

The iconographic spectrum of death as a necrotic effect of the socio-political system seems to emerge as the exhibition progresses. In Gore Capitalism (2010), Sayak Valencia describes this emergence as “necro empowerment” — the process wherein the unrestrained use of violence, linked directly to a minority’s condition, becomes a factor of capital accumulation. The retrospective thus becomes a radical critique of the concept of violence as applied to its political, social, linguistic, and cultural dimensions.

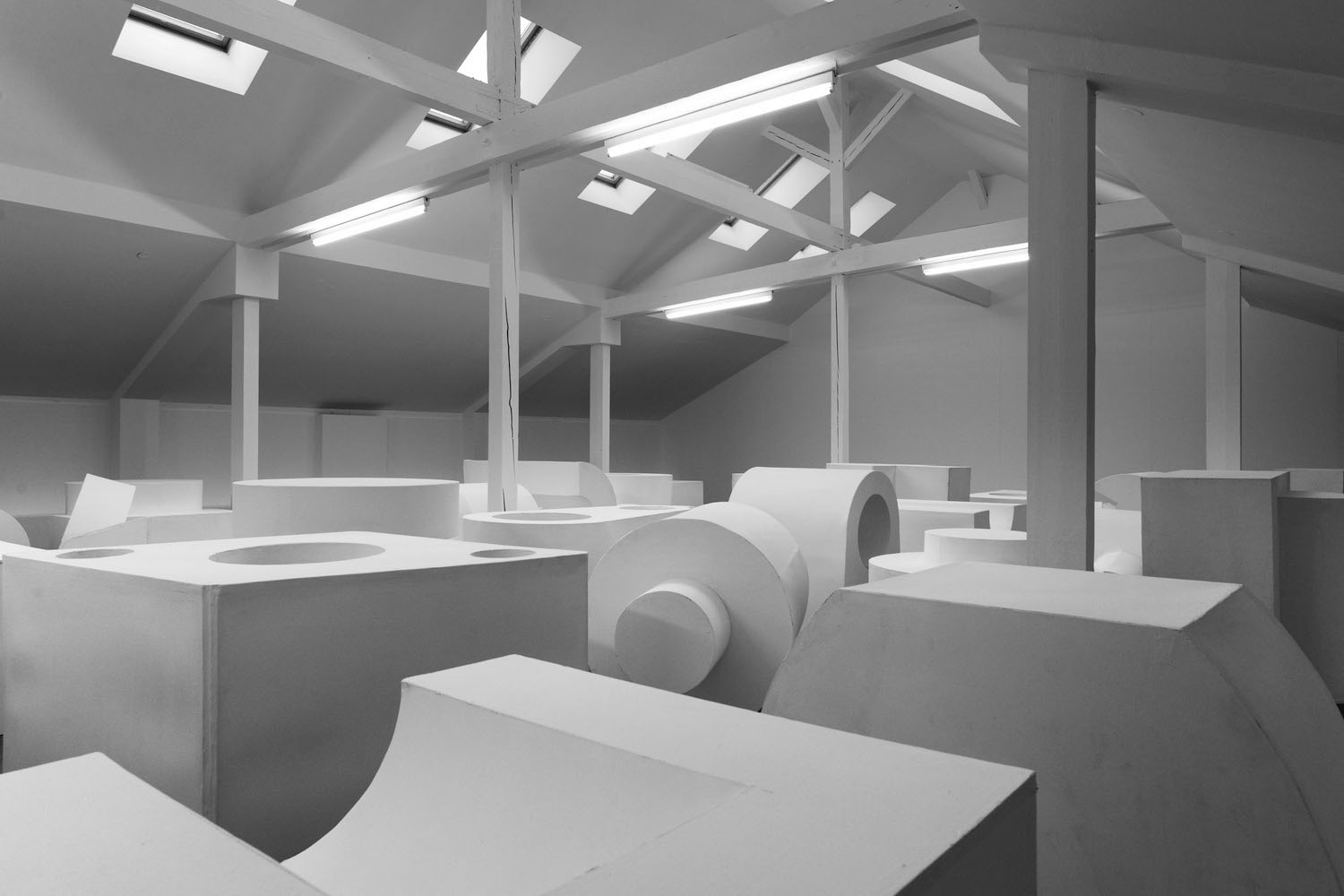

A photograph of the giant caged used in The Year of the White Bear and Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West (1992–94) welcomes viewers into the bewildering hubbub of the first gallery. Written, directed, and performed with artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, the interdisciplinary project consisted of a multimedia installation, an experimental radio soundtrack, and several performances that explored and interpreted the violent history of the so-called “discovery” of America, in which Fusco and Gómez-Peña were presented as “undiscovered Americans” from an unknown island in the Gulf of Mexico.

In the documentary film The Couple in the Cage: Guatinaui Odyssey — directed by Paula Heredia in 1993 after the artists invited her to their final performance during the Whitney Biennial in the same year — fictional language becomes a tool for understanding the postcolonial condition. It highlights the intricate relationship between the museum and colonial history from a non-Western perspective.

A similar approach to institutional critique is evident in other works by Fusco, such as Sudaca Enterprises (1997), a guerrilla performance presented at ARCO Latino Art Fair in 1997 with Juan Pablo Ballester and María Elena Escalona. The artists dressed in ski masks and Quechua knit hats, and sold T-shirts imprinted with texts that compared the price of Latin American Art in Europe with the cost of selling at ARCO and the cost of surviving as an undocumented Latin American immigrant in Spain.

In this way, Fusco’s practice becomes a metalinguistic process engaging with postcolonial discourses from a feminist and psychoanalytic perspective. These references have evolved throughout her career across a range of mediums and contexts, including documentary and sci-fi films, theoretical texts, speculative fiction, political activism, and poetry. In her lecture-performance Observations of Predation in Humans: A Lecture by Dr. Zira, Animal Psychologist (2013), Fusco portrays the chimpanzee psychologist Dr. Zira from the movie Planet of the Apes (1968). Dr. Zira returns after twenty years in hiding to share observations on the predatory practices and aggressive tendencies of members of the genus Homo. This role-play from an animal’s perspective fosters a practice of identification to look at human behavior from a different angle.

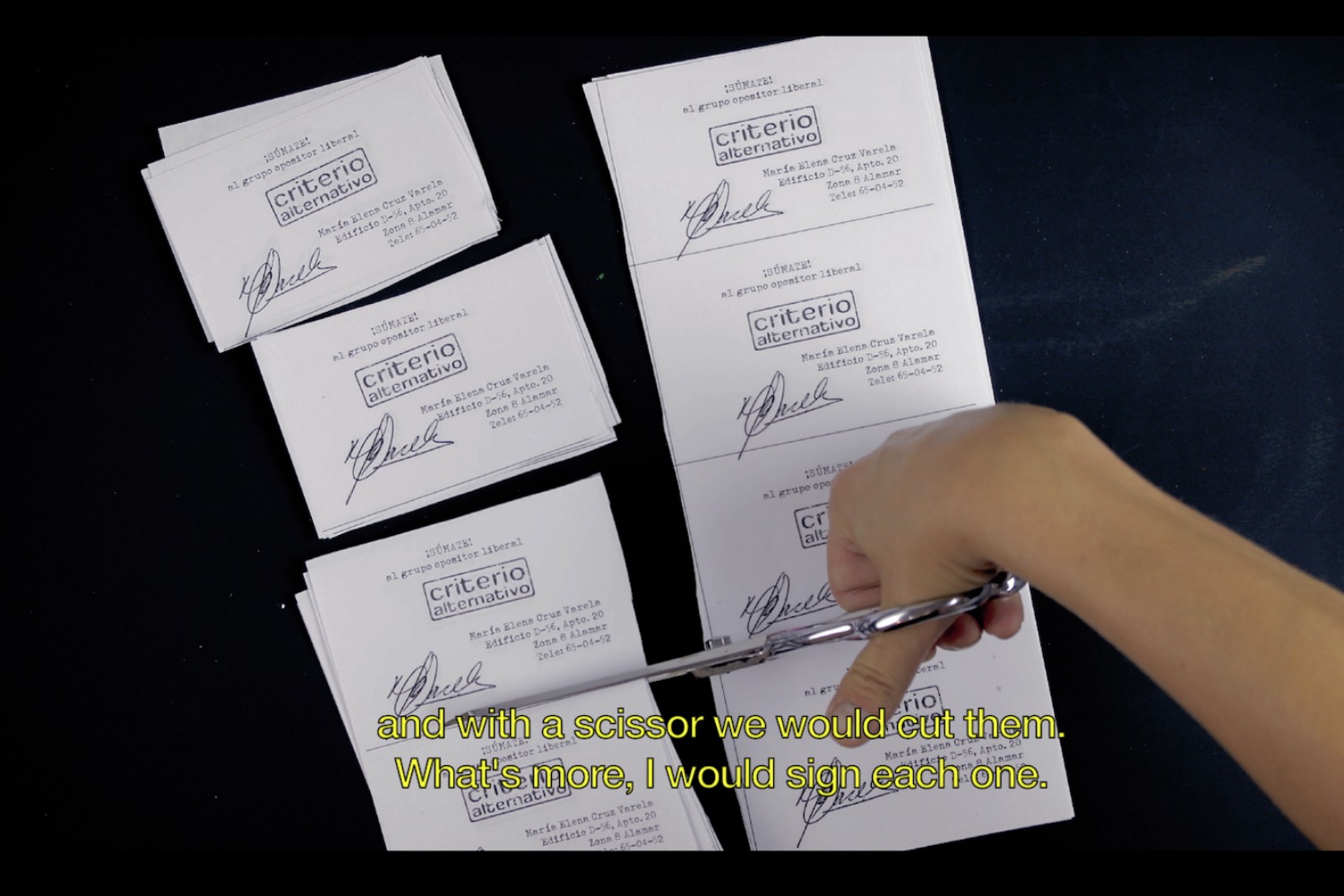

The kaleidoscopic curatorship of the retrospective culminates in the last room, featuring the works The Empty Plaza (2012), La botella al mar de María Elena (2015), and To Live in June with your Tongue Hanging Out (2018). The latter is a video in which Lynn Cruz, Amaury Pacheco, and Iris Ruiz attempt to commit to memory a poem by Reinaldo Arenas, a homosexual poet and political dissident of the regime. In these final works, Fusco focuses on the political situation in post-regime Cuba. The relationship between poetry, regime politics, and censorship is rooted in what Gramsci described as the concept of indifference — another facet of Fusco’s work, which leaves the audience with the sad consolation of impending political responsibility:

Indifference is the dead weight of history. It serves as the leaden ball for the innovator, acting as the inert matter in which the brightest enthusiasms often drown. It forms the swamp that envelops the ancient city and defends it more effectively than the strongest walls or the steadfast chests of its warriors. This is because it engulfs the invaders in its muddy whirlpools, decimating and discouraging them, and at times compelling them to abandon their heroic enterprises1.