In “Mirror, Mirror on the Wall,” a text by Emma Frith that accompanies Ellie Pratt’s exhibition “Taste Maker,” the author writes about Pamela Anderson, the iconic model and former Baywatch star from the 1990s who has openly discussed her fear of mirrors, a condition known as eisoptrophobia. This anxiety is fueled by the discomfort of seeing oneself in reflective surfaces, from an actual mirror to the black mirror of a computer screen or a phone. There are no mirrors in Pratt’s exhibition, but there is a sense that the gaze of objectification underpins much of the work, including how we might view it.

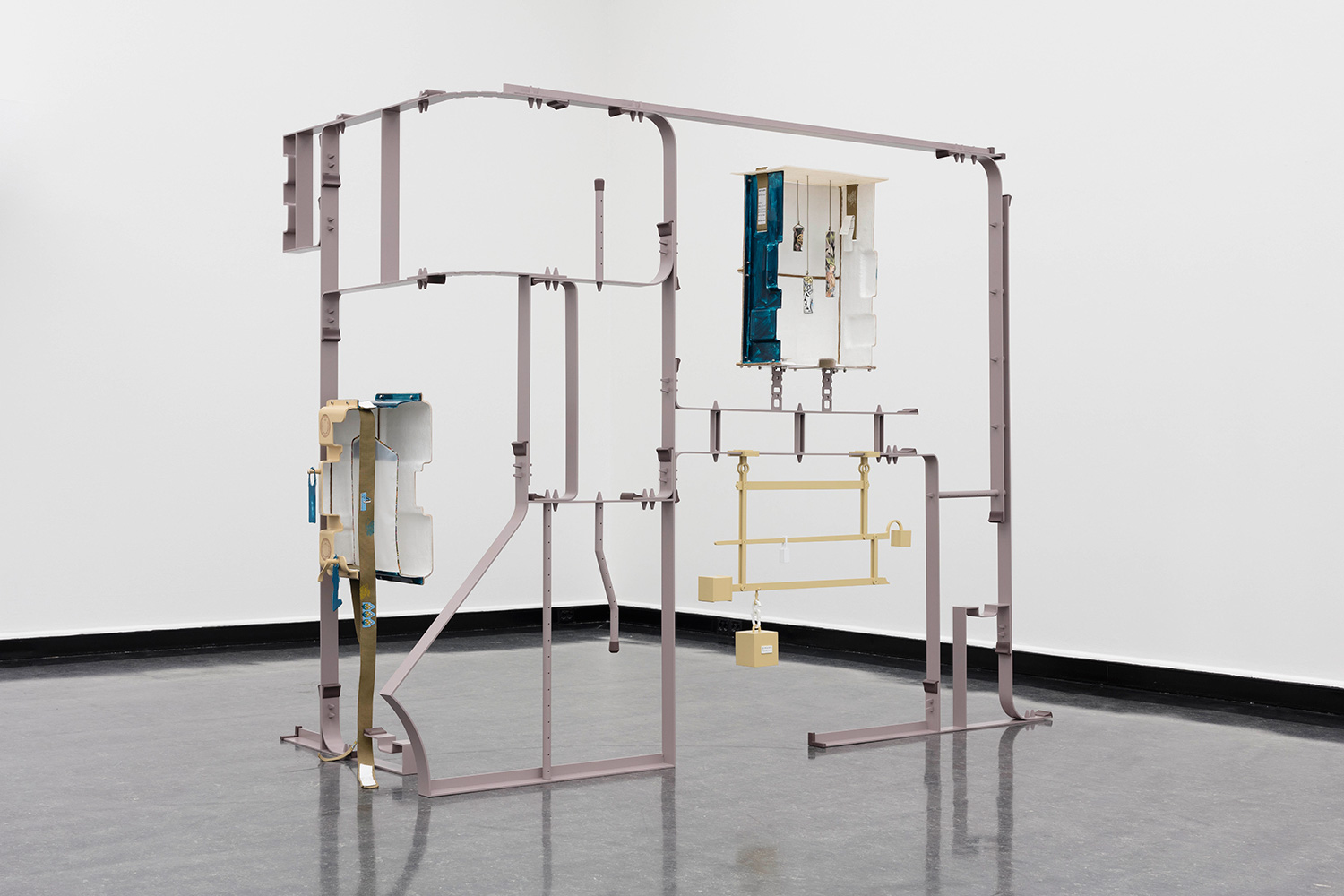

South Parade’s spacious new London gallery showcases a plethora of paintings by Pratt, as well as one drawing, which warp and unsettle a conventional portrayal of the female visage. The exhibition delves into the quiet inner workings of a slippery psyche while seemingly examining the historical tendencies of artists and advertisements to exploit the bodies of women through images.

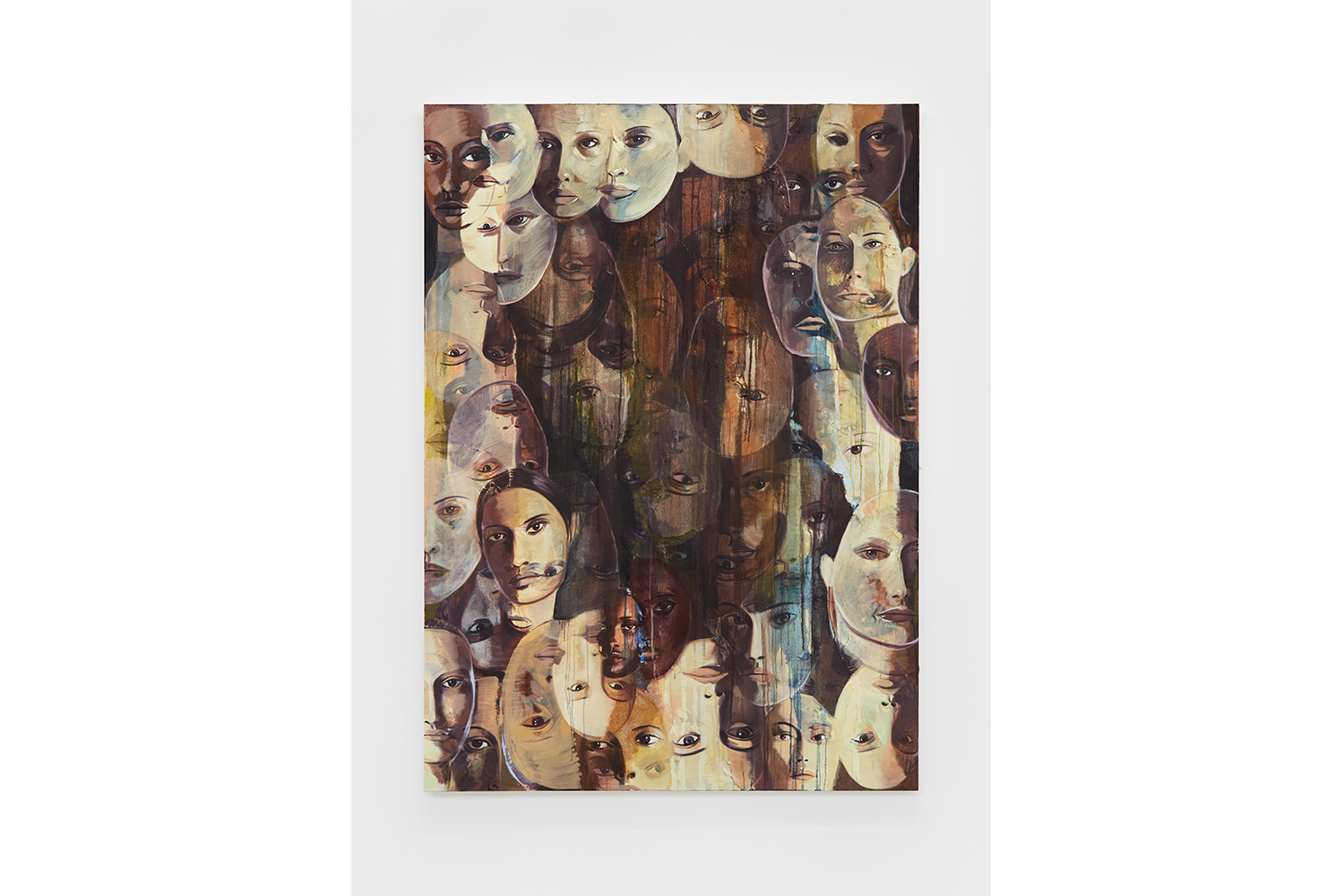

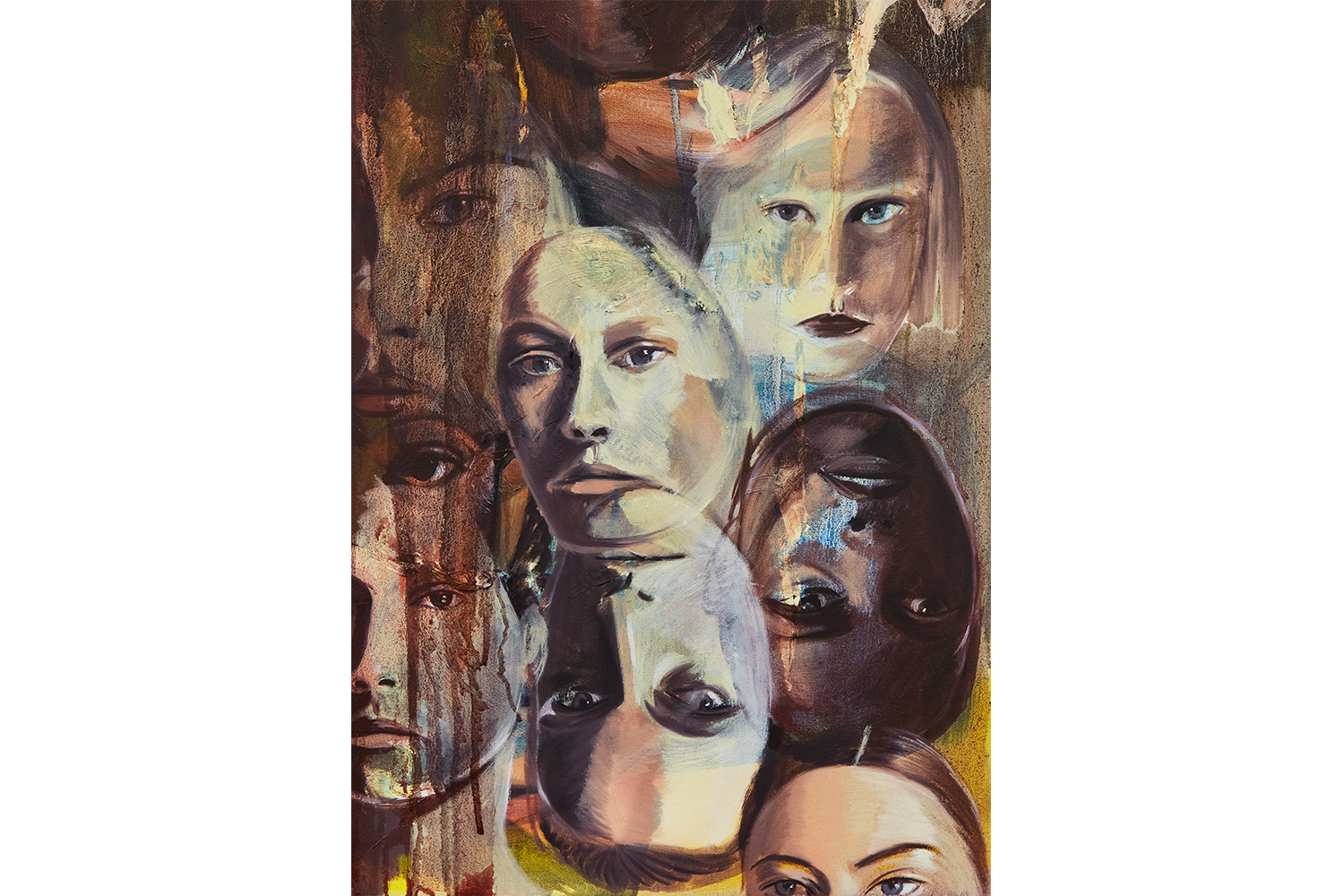

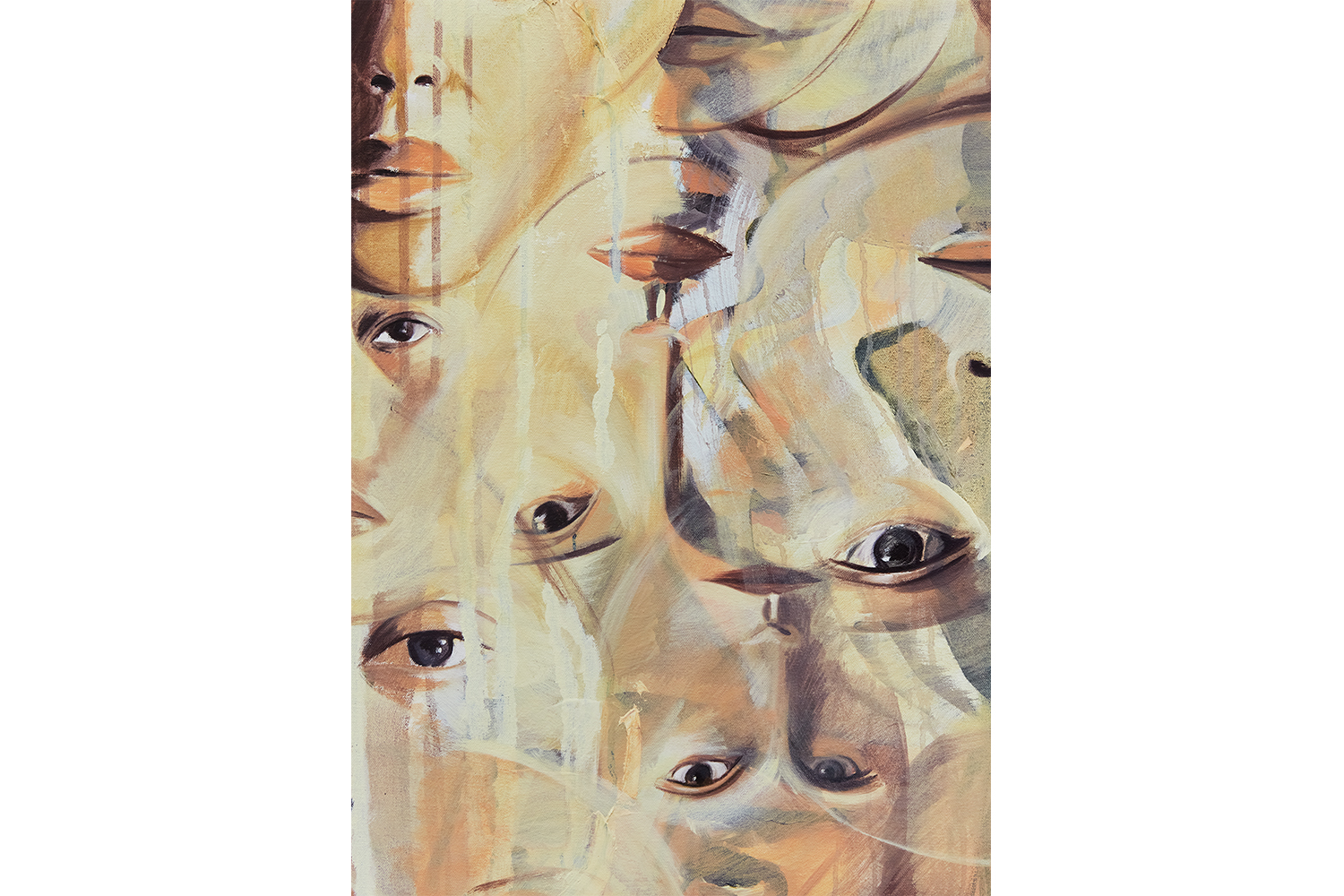

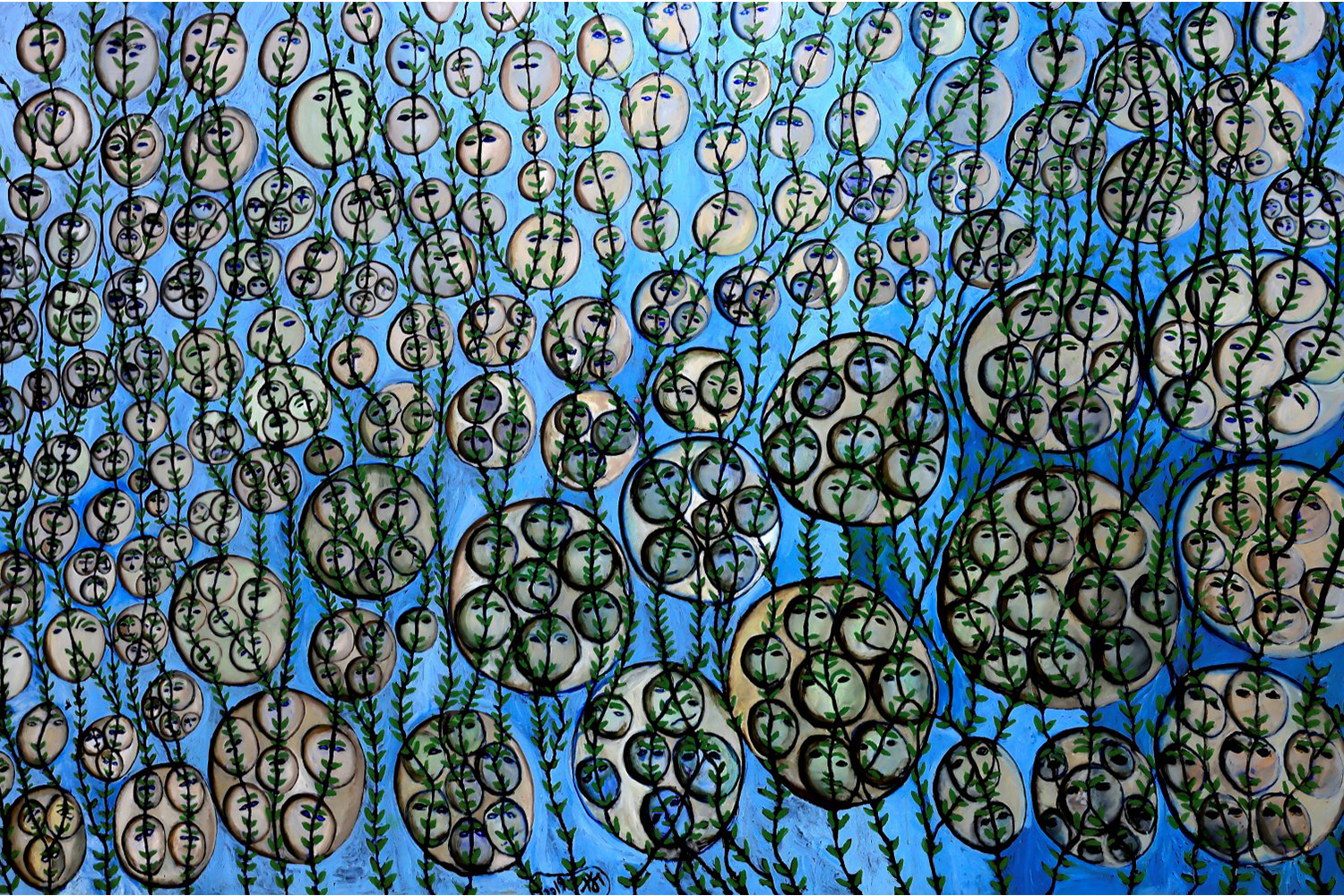

Upon entering the gallery, the viewer is trapped between a multitude of stares, an exchange between two paintings, Reflections 1 and Reflections 2 (both 2023). The paintings contain a myriad of facial fragments; eyes stalk the observer across the entire gallery space, never blinking. These faces suggest the emotionless, mundane gestures of models on a runway or in an advertisement for fast fashion. Some of them appear upside down, which throws the eye of the viewer into a space of disorientation. There is something compulsive about the layering that occurs across Pratt’s paintings, an obsessiveness that the blank stares of their subjects refuse to acknowledge. The lack of a focal point in these works draws the viewer in closer to the surface, which is rough and textured, scarred, as if it might have been attacked into existence. Minute details, soft and surprising cloudlike pigments, coat each brushstroke.

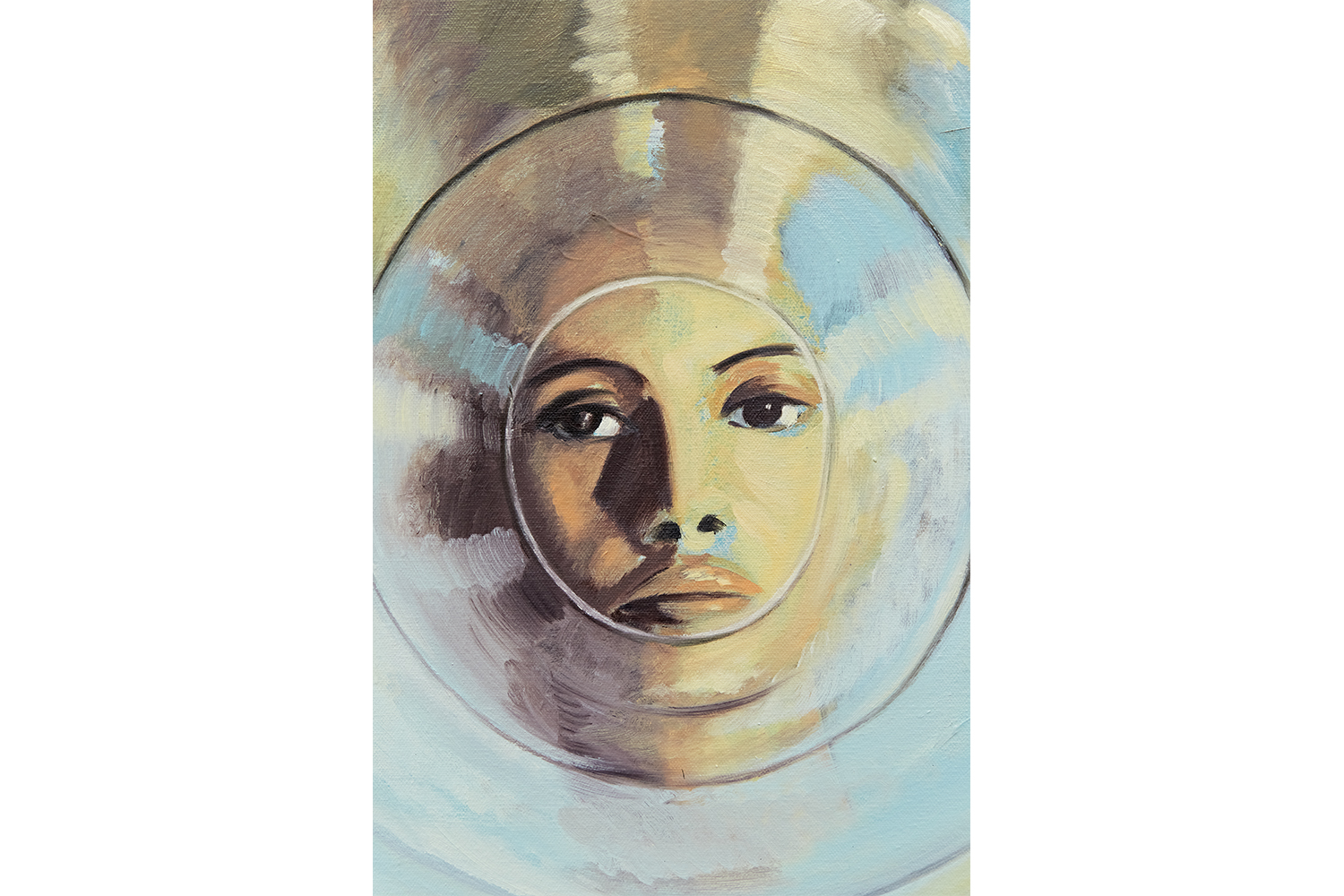

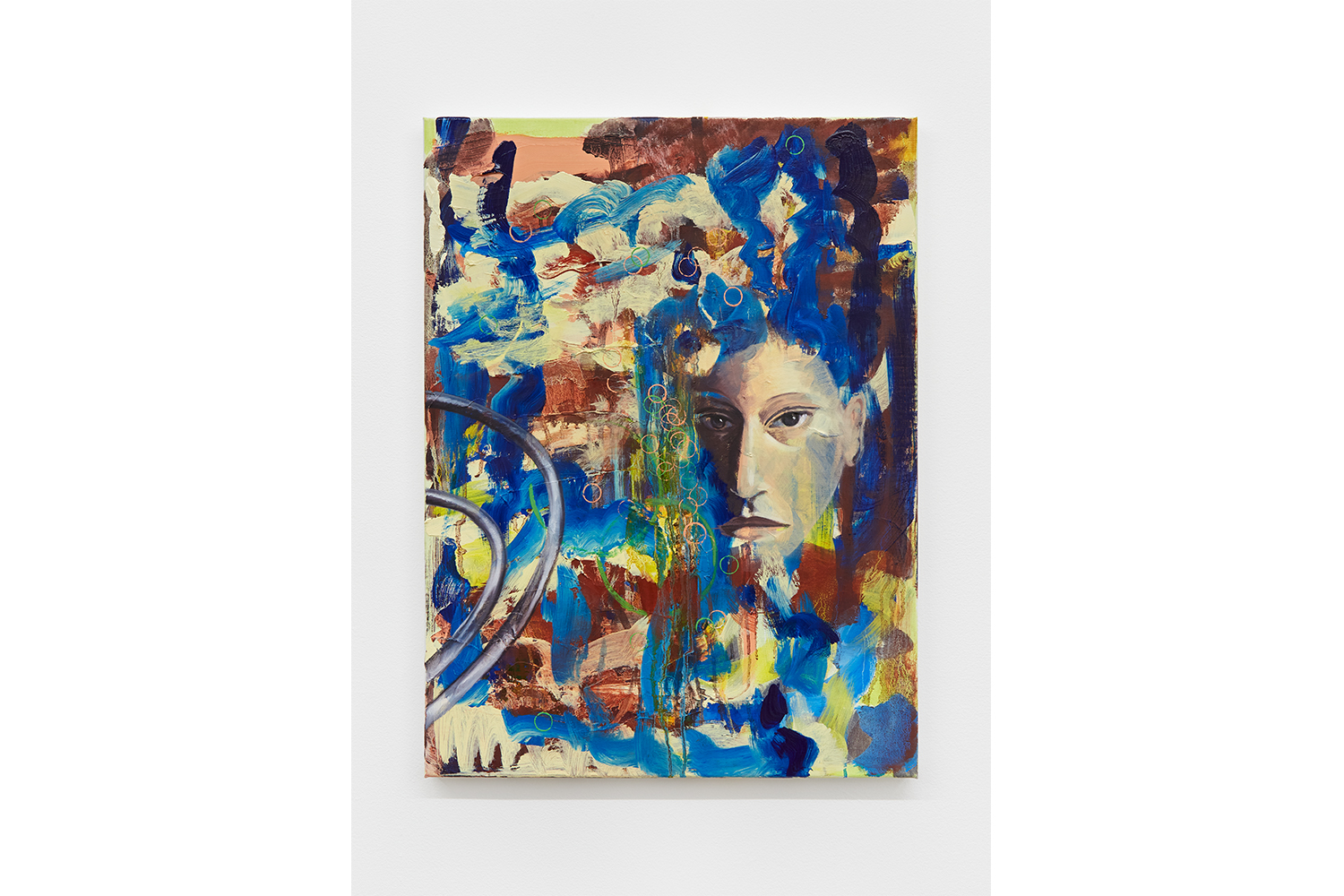

Pratt’s visual vocabulary and painting methodologies are not fundamental or fixed; she jumps registers from piece to piece. Between Reflections I and Reflections II rests a much smaller work that looks as if it could have been painted by a completely different artist. This is a strength of both the curation of the exhibition and the work of the artist. The shift between registers gives space to the many watching eyes contained within the works. Reflection (A Girl) (2023) is reminiscent of a makeup cleaning wipe, with the residue from a night out or a day at work left behind — the residue of an appearance, a performed image. In this work a single floating face peers outward, formless, fading, vanishing between the opposing energies in the rest of the room. What is the subject of this painting transfixed upon? Is it us, the viewer? What hangs opposite? What is the object of desire?

In Little Butterfly (The Shape of Longing) (2023), a flat, cartoonish, red-winged butterfly flies through a tunnel. The aesthetic of this butterfly recalls a sticker that a child might apply to a notebook. But where is this butterfly traveling? The tunnel of Little Butterfly seems to make a reappearance in the second room of the exhibition, in a work titled Engine (2022), but this time a voguing face stares back at the viewer. No answers are offered, but a transition has occurred.

Roland Barthes writes that “you never see your eyes unless they are dulled by the gaze they rest upon the mirror or the lens.” In a similar vein, these paintings may not offer us an opportunity to see our eyes, but there is an unsettling and sophisticated intensity throughout this exhibition that makes it feel as if we are looking far deeper into ourselves than we might like to.