What is creation if not negation — if not a definite stroke distinguishing some thing from the next? Death is the ultimate negation. It is the tightly sealed vacuum always close behind presence. Death is not the opposite of life but its purifier. Dominique Knowles, whose solo show “My Beloved” is on view at Hannah Hoffman, makes paintings about his titular beloved: his dead horse. He intends to make permanent the substance of memory, to bring it into the oil and threads of linen. His paintings lead with their glowing affection. They are sensual, a thankful oasis of feeling.

Knowles’s obsession with materials and tactility is the productive motor of the paintings, which suggest fleeting scenes that might have been found on cave walls. They are painted with pigments the artist mixes himself. Brushing the canvas recalls the experience of brushing the horse. The act and materials possess a ritual presence, linking disparate events.

In “the altar” the artist comes close to depicting a narrative. (All the works in the exhibition are identically titled The Solemn and Dignified Burial Befitting My Beloved for All Seasons, 2023, but the artist’s working titles are useful for distinguishing them). In the left panel, the artist renders himself in alluvial tones as a nude Rückenfigur, bathing knee-deep with arms extended, swaying like tree branches, his head turned toward a distant darkness. The central panel shows his horse in radiant solar colors, doubly painted in a way that suggests motion and liveliness, the head tilting to graze. It is the horse at sundown, emblazoned in a last burst of light. On the right is the same horse, dead, hanging upside-down by its legs from a crane. The sequence follows a tragic archetypal pattern: the beloved sought, the beloved attained, and the beloved lost. This scene of a dead horse — craned upside-down by the legs across the sky to his final resting place, in a shape resembling a crucifix — is a peak behind the curtain, a material performance of spiritual transmutation. It is this type of mystical approximation that permeates Knowles’s art.

Certain paintings in the exhibition ask for more attention from the artist. In “the cliff” and “the green horse,” the compositions and marks appear only partially developed. Knowles stopped too soon. There is a pervasive crudeness to all the works in the show, but in these two the pendulum is too far toward the underdeveloped and chaotic. In “the crucifix,” figures and scenes have also been foregone for swatches of color and atmosphere. The primary rectangle is roughly divided into three warm planar zones, leaving the secondary square greenish area somewhat isolated atop the composition. Initially, it is difficult to find one’s ground. The crucifix is an altarpiece, a locus mundus — it is the core prismatic object around which all else is articulated. This painting converts the essential aspects and attributes of the works here presented into a unified and discrete object. The unusual linen is itself shaped to suggest a rider on horseback. The success of this work is that the aesthetic resonance of Knowles’s compositional and formal strategies stand on their own. Some foresight guided the improvisation. If Knowles’s works are painted from dreams or reveries, this one followed the vision with greater fidelity.

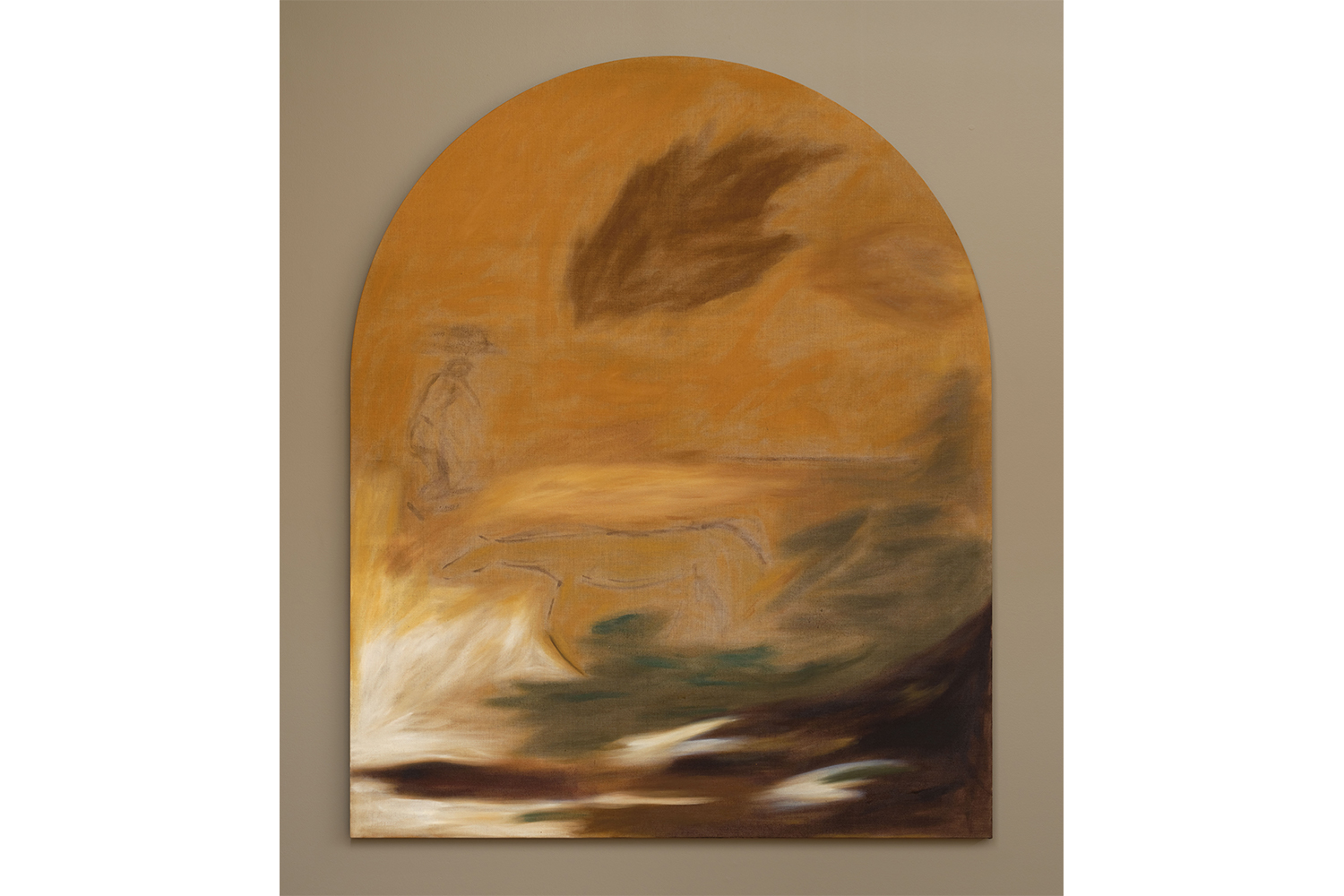

In “the Zen painting,” the first of four paintings shaped like church windows (or tombstones), there is a copper sky with a fiery cloud, a pasture with a horse, and a small person on the horizon. The foreground marks are a sweet spot of the whole show, indulging in a slick and unctuous texture. Flanking the doorway to the gallery offices are two burial paintings. Both are painted with deep brown tones that seem to crumble on the surfaces. The left of two burial paintings, “bone burial,” is hypnotic and rewards extended viewing. Executed like an inverse drawing, it abstractly depicts the intertwining forms of the horse buried with its rider, submerged in an earthly matrix. In “moss burial,” a horse is nestled almost in a fetal position in a soil womb.

The content is ultimately a pretext to explore the sensual and aesthetic properties of his materials within the boundaries of a consistent atmosphere. When these material attributes fall short of satisfying there is little left to savor. When Knowles is formally successful, the immediate experience of the painting is so compelling it renders the content to some degree superfluous. And once removed from the immediate presence of the works, what lingers is the content: the atmosphere, tone, and “primordial silence” with which the themes of death and love are explored. At their core, these works are adorations of the erotic aspect of art.

Perhaps Knowles’s hand is not as mature as his heart. Any good artist knows to limit themselves. The obsession with his dead horse throughout his oeuvre is a limiting mechanism. Knowles uses this thematic narrowness to explore the other aspects of his art, and probably also for his own recognizability on the market. But what Knowles needs now is not parameters of content but parameters of form. He would benefit from definite standards of execution and repeated rendering strategies throughout. A more rigorous execution would elevate the numinosity of this body of work by nesting the spontaneous elements of Knowles’s painterly behavior into more rugged and lasting forms.