In the heart of Tokyo in the mid-1980s, a young girl first encountered the enigmatic allure of contemporary art. Since then, she has hopped from museums to galleries, visiting biennials in Europe and the US, and meeting artists and their art. Nearly forty years later, in the same spirit of discovery, she stepped into a museum in Kanazawa and witnessed Alex Da Corte’s art for the first time.

In a room, she sat on a bench in front of a projector and watched a sequence of intriguing actions on a screen. A white-powdered hand emerged, stacking a pile of bread, while the song “Chelsea Hotel No. 2,” accompanied by guitar, resonated through the air. The hand proceeded to twist open a Coke bottle, squeeze the liquid from another bottle, peel a banana, stack another slice of bread, and flip over a slice of baloney on a bucket. Between those actions, shots of objects such as a gold-painted rose and cabbage on a trash can were inserted. As the sequence continued, the actions performed by the hands with the commonplace objects gradually acquired meaning, culminating in a poignant conclusion as the song ended. The video spanned only three minutes, but it left her reeling with an unexpected surge of emotion. A deep-seated feeling stirred within her, unseen but profoundly felt. But why?

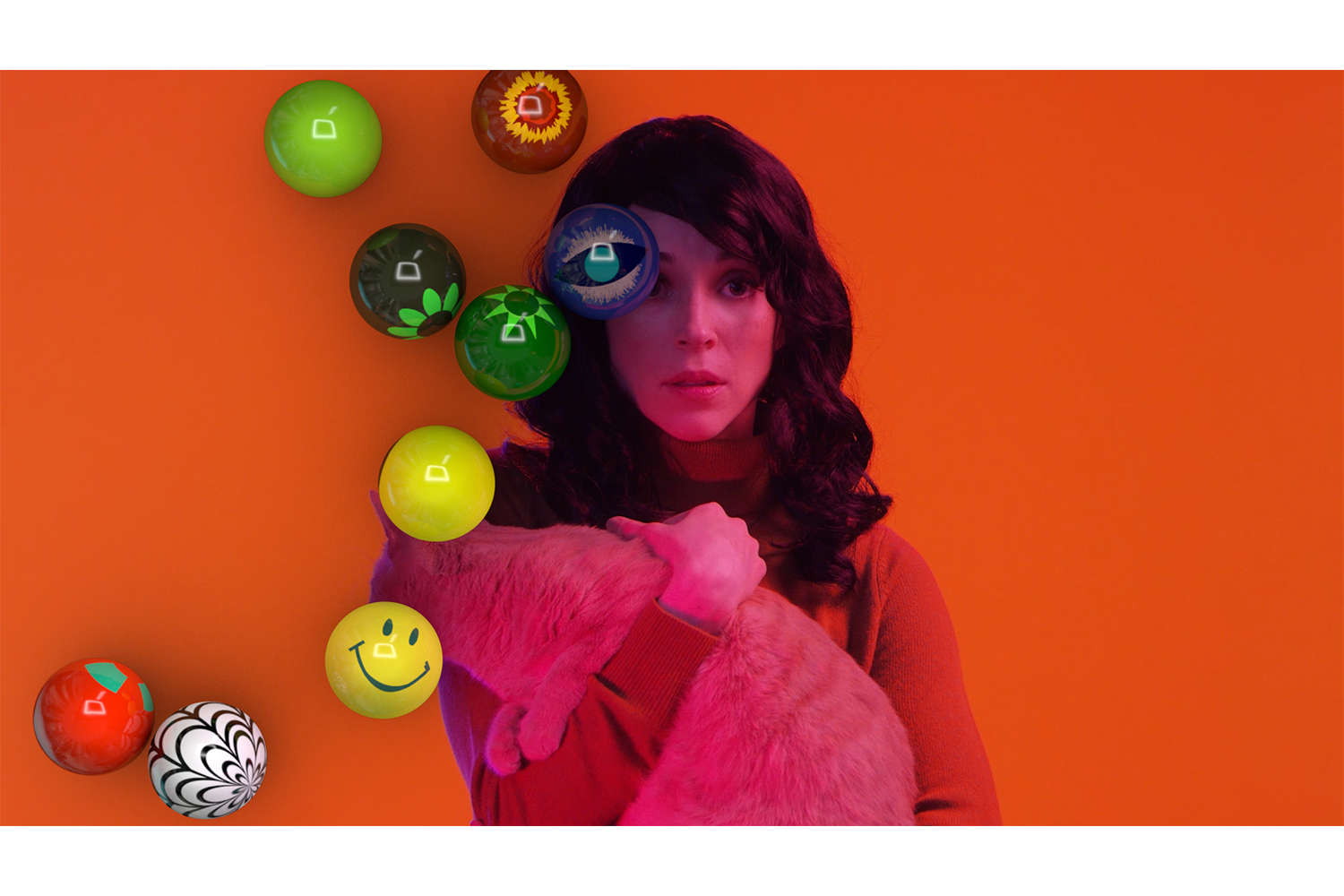

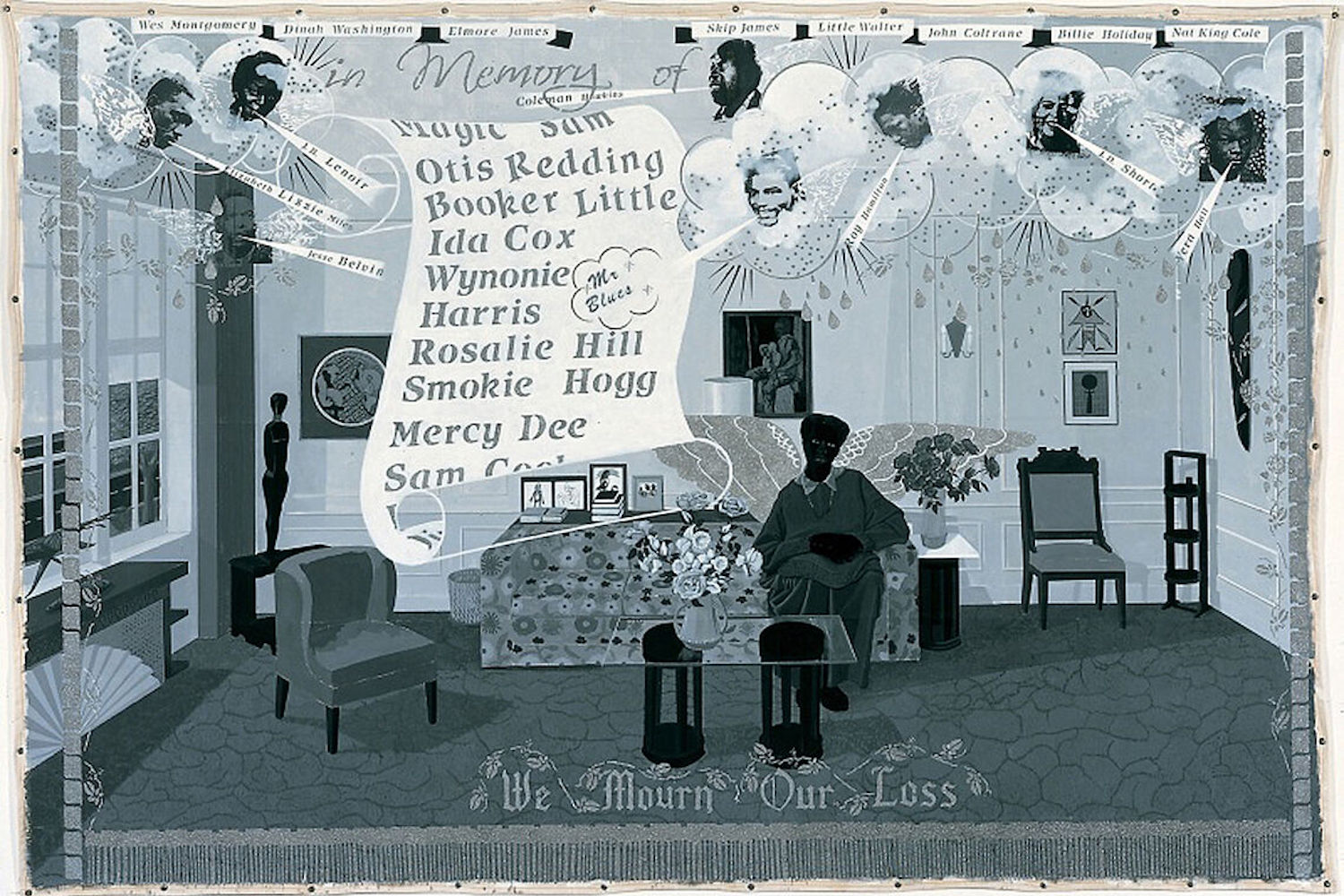

This emotional impact was foreshadowed at the beginning of the exhibition with ROY G BIV (2022), which unfolded within a set reminiscent of the Brancusi room at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. There, she encountered the emotive power of Da Corte’s world. What is the source of this power? Perhaps it arises from reflections on Brancusi’s sculptures, a reverence for Duchamp, Da Corte’s embodiment of Duchamp, or, above all, the element of color. This power feeds on personal schema — mental maps of memories and emotions constructed throughout our lives, as elucidated by Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget. This idea is starkly contrasted by Rubber Pencil Devil (2019), in which broad symbols, logos, products, and characters inundate the screen, wavelike, across five sections. Someone who grew up in Japan might understand their multiple meanings and ironies, but the imagery wouldn’t strike a chord. The work gives the impression of a visual spectacle detached from personal memories, highlighting the disconnect between perception and meaning. This dissociation is reminiscent of thought broadcasting, a symptom associated with schizophrenia — the belief that others are intercepting one’s internal thoughts and feelings. Considering that thought broadcasting as a mental symptom emerged with the popularization of television in households and has now shifted to online media, one wonders if the Mouse Museum (2022) represents an archive of the television generation. Meanwhile, the work underscores the vulnerability of our images. It emphasizes that we each color Brancusi’s white sculpture with our own unique palette; however, these colors are not shared among us.

Presently, the contemporary art scene reveals the pathos of its schema. It references and respects contemporary artworks and artists who engage with shared and unshared elements, as well as the individual feelings that remain unshared. It highlights the significance of artists’ endeavors in navigating our unease with the overwhelming flood of images in our culture.

Our susceptibility to images stems from a paradox; we share their meanings yet remain distant due to unique interpretations and emotions. The Da Corte exhibition showcases a journey, a dance that transcends this gap, shining light on contemporary art’s power to rebel against societal tendencies to commodify and ascribe meaning to images. Although we have some common understandings associated with images, we remain isolated due to our inability to fully grasp the intricate meanings and emotions embedded within each individual’s schema. “Fresh Hell,” the artist’s first museum exhibition in Asia, offers an opportunity to acknowledge and embrace resistance to the prevailing norms of commodification and the imposition of fixed meanings onto images.