Michel Foucault begins The Order of Things with an investigation of the seemingly nonsensical Chinese encyclopedia found in Jorge Luis Borges’s short essay “The Analytical Language of John Wilkins.” This fictional encyclopedia divides animals into arbitrary categories such as “belonging to the emperor,” “fabulous,” and “having just broken the water pitcher.” Borges’s text, and Foucault’s fascination with it, is premised on the paradoxical idea of an encyclopedia, meant to be a comprehensive tool, whose contents are contradictory and, ultimately, incomprehensible.

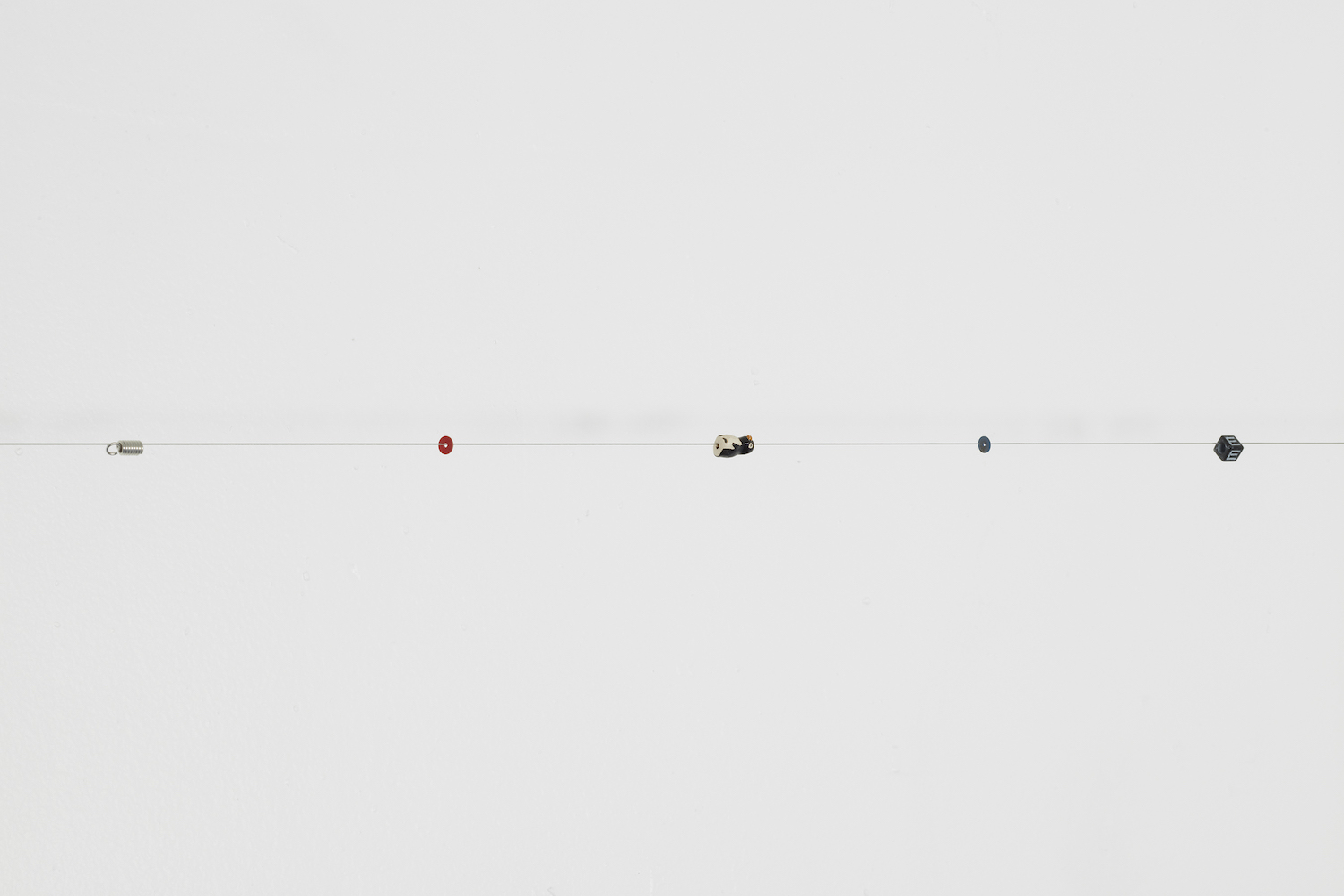

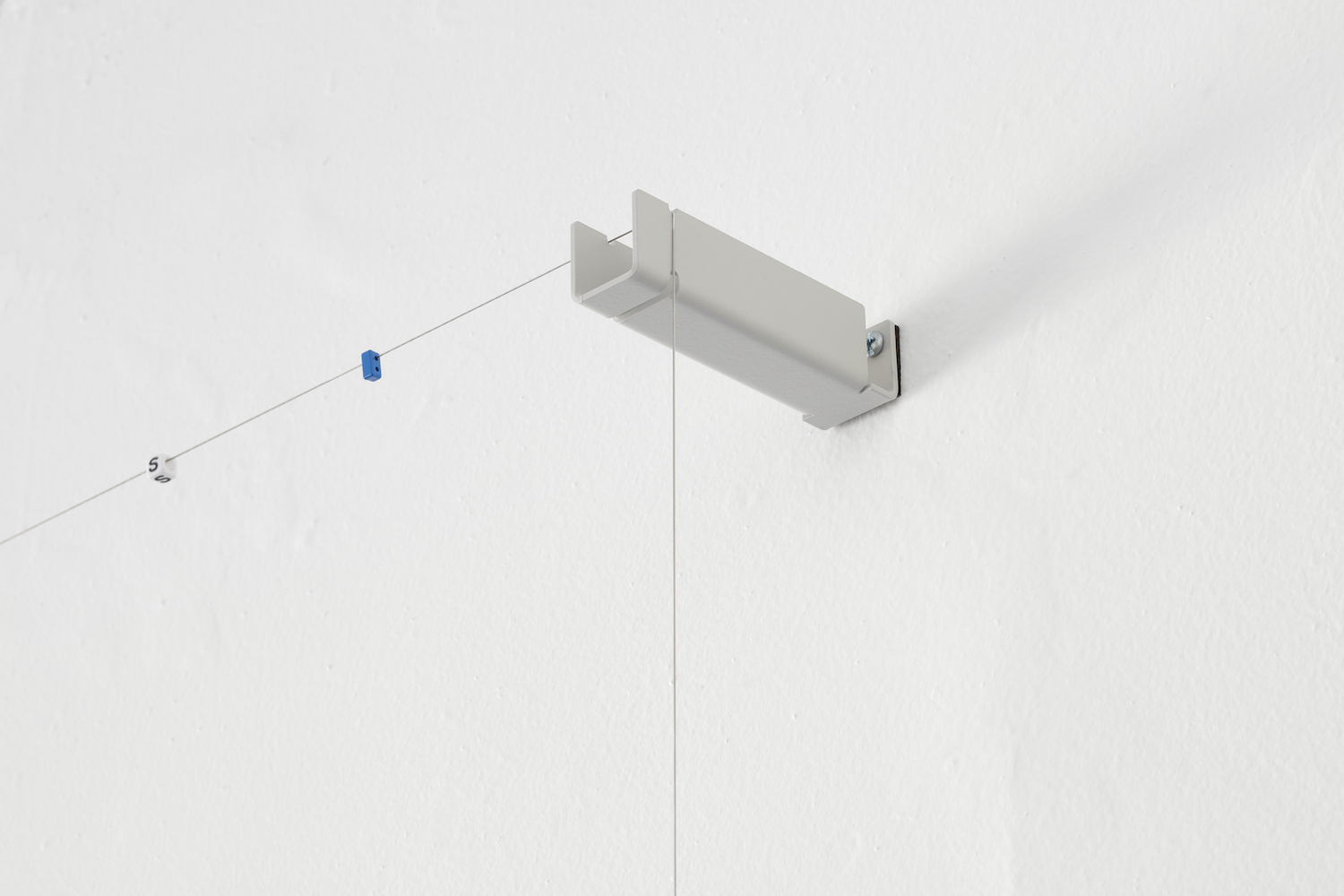

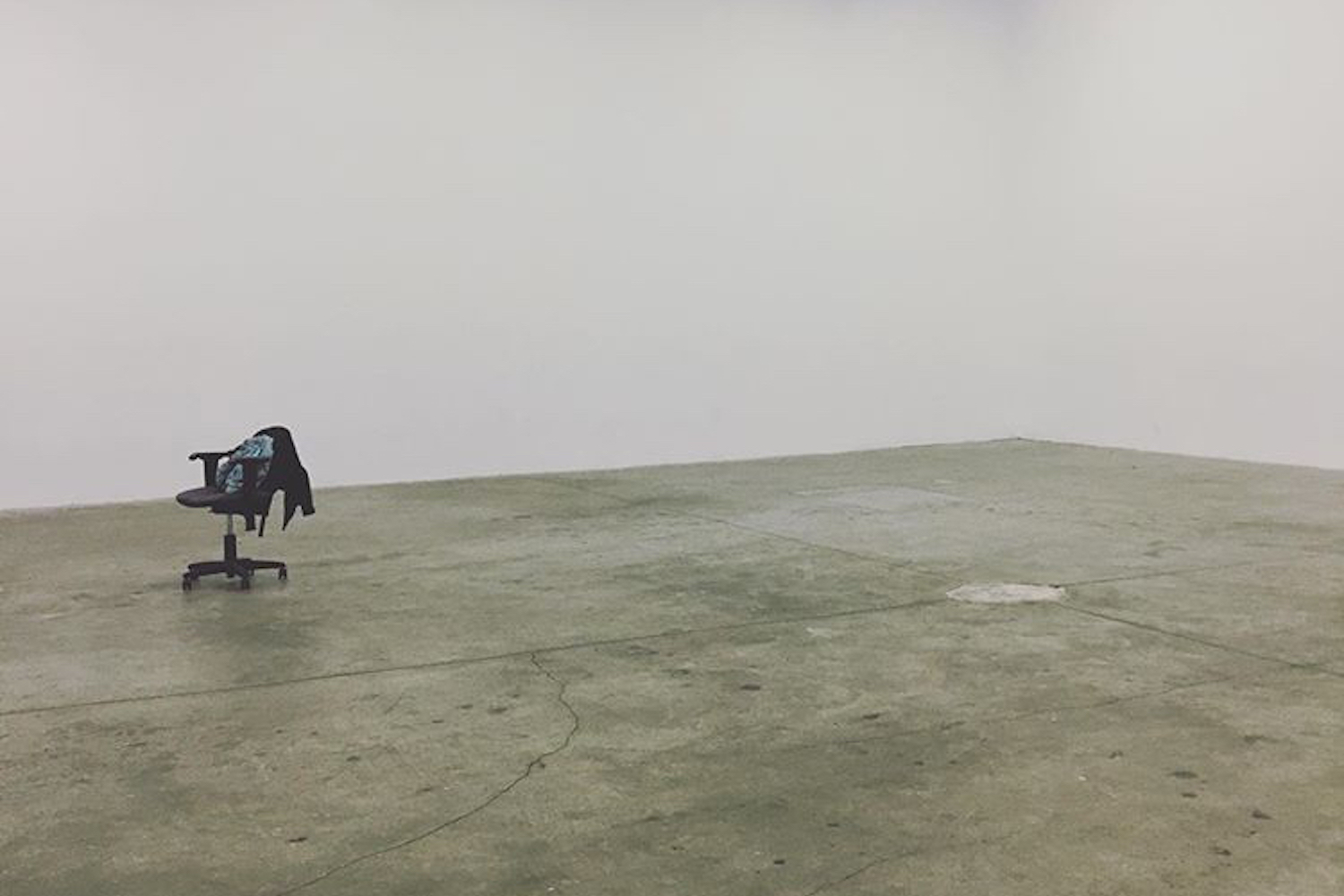

While visiting Steve Kado’s exhibition “Spring!” at Soldes Gallery, I was reminded of Foucault’s text. The artist strings together objects while preventing them from forming a larger whole, withholding a sequential system of information that it might suggest. On the second floor of a Chinatown building, the gallery is notably sparse. Only upon scanning the room’s perimeter did the works Fountain (EE), Fountain (HP), and Fountain (RRR) (all works 2023) even become apparent, immediately emphasizing the relationship with the architectural context they inhabit. Along three of the gallery’s walls, just below the ceiling, Kado has strung taut, metal cables. At each end, the cables are held by brackets only a couple of inches off of the wall; the cables turn downward on one end, weighted by cylindrical stainless-steel water bottles suspended a few inches from the ground. The length of the cables are determined by the length of the wall they line, not quite site-specific so much as site-adjustable. Each line of cable is strung with small objects: tiny springs, washers, beads, keychains, and plastic charms emblazoned with letters. Like the animals in Borges’s Chinese encyclopedia, it is not immediately clear how all of these tiny items cohere. The work does not provide clues as to what the relationship between a small coil of spring and a tiny clay penguin might be.

The only constant is the distance between each object. From this external constraint, a pattern intuitively emerges in each object’s placement along the line. Or more so a rhythm. Something like every third object is blue; longer, horizontal objects alternate with square blocks. Distinguished from the logic of language, the sequences of beads suggest the phrases of improvised music. The work references Kado’s ongoing performances of solos for the drum machine, one of which will be held at the gallery during the run of the show. Like listening to improvised music, the viewer here can sense a logic to the work that remains just out of reach. The placement of a washer is not random but it isn’t exactly predictable. Despite this, some elements along the cable do fit together more clearly. Short phrases form from the interspersed lettered beads on each cable. In an exhibition defined by its controlled minimalism, the words reach out as if to provide some sense of orientation for the viewer.

It is tempting to cling to the phrases along the cables, “RATS RATS RATS,” or “EFFORTLESS ELAN,” as clues revealing something fundamental about the works themselves. However, like Borges’s Chinese encyclopedia, the “truth” of any given phrase here is secondary. The fundamental operation of the words is rather in the collection itself. Manifested physically, the letters exist side by side with other assorted objects without cohering into any larger narrative. These trinkets strive toward some greater logic, but this is perpetually deferred. After all, none of the letters are directly next to one another; only in our search for meaning do we force the letters together into words. As Foucault writes, “What is impossible is not the propinquity of the things listed, but the very site on which their propinquity would be possible.” He goes on to explain that it is only in the “non-site” of language that this collection of animals could exist together. For Kado, this non-site is the gallery, a void circumscribed by the work itself. However, the lesson of the Chinese encyclopedia is not that the list is somehow incorrect. Rather, it gestures at an epistemology beyond our comprehension. In Kado’s work, language is not held as superior to the nonrepresentational objects; rather, primacy is simply given to smallness.

At the end of each cable is a bottle filled with water that maintains the sculptures’ tension, keeping the works in a state of suspension that reflects the equilibrium between meaning and its inaccessibility, between the individuality of each small object and its function in a larger ensemble. Notably, the water bottles are not closed, inviting yet another form of tension. There is an ever-present danger that, as water evaporates, the entire artwork could collapse, filling the void of the gallery with water and beads. This is of course unlikely; however, if the small objects do not fill the gallery, the evaporated water does.

In attempting to showcase what is beyond reach, visually, linguistically, or conceptually, Kado’s work presents its audience — and its photographer, as the work is effectively unphotographable — with a challenge. The viewer is asked to engage with work that is as much about contouring an absence as it is about the actual silver lining.