Intermissions is a regular column in which creatives are invited to discuss alternative points of view on art, typically with a social and political perspective and a literary approach.

Act I – A Pimp’s Beach

Ghosting came into being during a blue period in New York City when yellow cabs were testing a nigga’s patience. It was the pandemic that never got its flowers. Not surprisingly, ghosting was inspired by NYPD’s “stop-and-frisk,” the practice of detaining, questioning, and searching innocent civilians on the street for weapons and other contraband. How the “medallion virus” worked is a taxi driver would establish that a hypothetical passenger was Black and register them as a person of interest. As the person of interest approached the vehicle, a cybernetically enhanced eye designed to identify what species of Black he might be would protract from the driver’s eye socket. With one brow raised to his hairline, chin in hand, the driver would then contemplate a drop-down menu of options displayed over their iris. Is the person of interest: A) the eleven o’clock news type of Black Man; B) the type of Black Man that don’t tip; C) the hop the cab type of Black Man; or D) going to visit a cousin somewhere mad deep in Brooklyn type of Black Man?

As a precautionary measure, the taxi driver’s knee-jerk response is always E, all the above. The person of interest is classified as a suspect, wanted for any number of crimes reported on the eleven o’clock news, some that went down deep in Brooklyn, won’t tip, and will most likely hop the cab before you even get to Brooklyn. At this point, the cybernetic eye retracts. Impulsively, the would-be passenger leans over to press his face into the passenger window, barks at the driver an incomprehensible number of expletives while waving both middle fingers through the air. If he’s “I’m not the one to be fucked with” upset, he’ll bang down on the roof of the car, kick the tires, or worse, waste a fresh dollar coco-cherry ice all over the windshield. In retaliation, the taxi driver rolls down the passenger side window, leans over, and shouts, “No, fuck you, you Black muddyfuckah!” and hauls off. And so, this was the dance.

Today was my lucky day. I miraculously caught a cab without incident. In a hurry, I took a risk and decided to wait on the northside of 110th Street — in front of the bulletproof Kennedy Fried Chicken restaurant — instead of the more reliable south side. To any medallion driving by the chicken spot, all Black men looked like the Central Park Five Donald Trump made us out to be. That day, Driver No. 523689 appeared to be in good spirits. Relieved he could rule out Black type A, B, C, D and E, he let go of all the anxiety trapped in his lungs, adjusted the rearview mirror, and started the meter.

“75th and Madison please, the Whitney.”

While we waited at the light, I took in the familiar “Summer in Harlem” hustle and bustle on the block at Schomburg Plaza. It was a pimp’s beach. Thumbing through, I could count few familiar faces except the comings and goings of delivery boxes with blue smiles painted on them. Then, like an eclipse, a shadow would drift past the brim of a fitted cap, or a pair of shoulders would bop to the beat of someone’s stride, “Yup, there go Dee Dee and Foo Foo.”

Schomburg is located two blocks west of Spanish Harlem. It was named after writer and activist Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, a native of Puerto Rico who became an important intellectual figure during the Harlem Renaissance. It was originally an affordable housing complex that consists of twin thirty-five-story octagonal towers on the northeast corner of Fifth Avenue and one eleven-story rectangular mid-rise slab on Madison Avenue. In 2005 it was sold to a bank and given a new name. It was my childhood home when they called it Schomburg. When they called me an adult and demanded I pay rent, it became known as The Heritage.

A sprawling outdoor plaza separates the three buildings. It looks almost invisible today, but back when quarter waters splashed down our throats and our fingers were sticky from Eye Popper candies too sour to keep in our mouths, when we were to be seen and not heard, the plaza was the great American frontier where we could be whatever we wanted to be. From sunup to sundown, we’d emulate the absoluteness of childhood, never enough time to do it all.

In the summer we’d play games like 2-on-2 on empty garbage cans, Skelly, Double Dutch, Freeze Tag, and everyone’s least favorite, Hot Peas and Butter. Hot Peas and Butter was everyone’s least favorite because it was the only game where everyone paid a price. It was like Freeze Tag but with a painful outcome. When, not if you got caught, you were whipped with a long leather belt fashioned with a sharp metal tip. No excuse could get you out of playing this game. If you sat out it meant you were a punk, and if you were a punk, you might as well never come outside again.

To start, we’d meet at the bottom of the plaza stairs or “home base,” where one person was chosen to hide the belt. After finding the perfect hiding place, they’d shout, “HOT PEAS AND BUTTER!!! COME AND GET YOUR SUPPER!!!” which was everyone’s cue back at home base to spread out all over the plaza to find it. If it wasn’t you that found it, a scream the size of an M-80 would signal the belt had been awakened, and which direction to run away from. As years passed, right in front of our eyes, the sun would set on the plaza and become something more heartbreaking. Hopelessly, Arturo Schomburg’s plaza looked more like Nino Brown’s The Carter, succumbing to drugs and violence, closed for so long now I can hardly remember it being open at all.

Driver No. 523689 slipped into Fifth Avenue traffic. The city had recently mandated a new high-tech video-and-fare system to be installed in all thirteen thousand yellow cabs by the end of the year. On this new built-in monitor, Steve Jobs was standing before a large crowd of Apple employees and tech enthusiasts at a keynote address to promote the first-generation iPhone. Somewhere between slides nine and ten, Jobs had magically transformed the BlackBerry blowing up in my pocket into a relic. I fumbled it out and opened a text from my best friend Betty: “IS YOU COMIN’ OR NAH!?”

“My fault, be there in twenty.” I was running late to pick her up. A few days ago, I persuaded Betty to work the matinee of a play she’s starring in so we could see Dan Colen and Dash Snow’s “NEST” at Deitch Projects. Dash and Dan had become downtown New York’s favorite late-night dish. Details about the show were sketchy, but I’d heard something about people doing a bunch of drugs and that seemed like a good start.

Betty and I both grew up in Schomburg. Same single-parent apartment in opposite buildings on the same floor. Our mothers were best friends, so naturally Betty and I became best friends. The four of us would spend most weekends together, visiting galleries and museums up and down Fifth Avenue.

While I was curious about most things, Betty was overwhelmed by everything, and needed to inhabit other bodies to help carry the weight of it all. Helplessly, she grew increasingly seduced by her desire to possess, which drove her away from the galleries of Museum Mile and onto the stages of Broadway.

Work had been steady, but now she was between productions. To stay sharp, she booked a role in artist Kara Walker’s Whitney Museum retrospective, “My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love.”

Act 2 – The Nipple Over Her heart

The playbill for Kara’s show reads:

Kara Walker is a painter, printmaker, installation artist and filmmaker. In 1994 she unveiled a daring reinvention of image-making in which she incorporated the genteel eighteenth-century medium of cut-paper silhouettes into her paintings. Drawing her inspiration from sources as varied as the antebellum South, testimonial slave narratives, historical novels, and minstrel shows, Walker has invented a repertoire of powerful narratives that addresses the very heart of human experience, notions of racial supremacy, and historical accuracy. The retrospective features more than 200 paintings, drawings, collages, shadow-puppetry, light projections, and video animations.

Betty was featured in a work titled Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (1994). In it, she plays the role of a young, silhouetted negress frozen in a fifty-foot panorama affixed to the gallery wall.

As the story unfolds, a commune of slaves is trapped in a monumental tragedy set on the banks of a cursed bayou. Read from left to right, nothing is what it seems. House lights dim as the curtain draws open on a moonless night. In the opening scene, a white Southern belle gleefully stands on her tippy toes to kiss a courtly suitor beneath a swag of Spanish moss. Suddenly, a scandalous pair of legs emerge underneath her dress. It’s unclear, but they appear to belong to a young boy, perhaps a slave, forced to make a cuckold of his master by entering her from behind. As the young boy fondles the nipple over her heart, her gasp awakens a pack of shrieking violins that crawl out of a sunken orchestra and up the spines of the audience.

Beneath the shadows of the moss, an outstretched hand gripping a jagged branch looms over the couple, threatening to stab them to death. Nearby, a young pickaninny clenches the throat of a dead goose and offers it to her mother. Her mother, whose body also appears as a rowboat, is carried away by the bust of a decapitated Yankee who delivers her to the banks of a marshy hill.

During this passage, a chariot of woodwinds swoops down from the sky to provide the audience with a moment of relief, but the poorly planned attack is cut short. Floating listlessly, the bodiless Yankee bobs his head up to the sky where, atop the hill, a spotlight draws our attention to another calamity. A second pickaninny, possibly the sister of the first, performs oral sex on the slave master’s son. As he climaxes, a whip pops through the air, commanding the brass section to march in. Damp with rape, our suspicions are confirmed as she cries out to her mother down below, helplessly wading in the swamp.

On the opposite side of the hill, a bug-eyed Betty peers out into the audience. Brass and strings quiet the way for a triumphant piano concerto. At first Betty appears frozen, one leg cranked in the air until a piercing chord sends her into a maddening rage. She bites down on her teeth, tightens her lips into a frown, clenches her fist, strains her biceps, and pounds her chest. Her body begins to shake and contort like a jackhammer. With one leg still set high above her head, she cocks down on the other, shifting her weight to her heel for support. Her nostrils flare out, eyes racing back and forth. She’s about to explode. In a defiant act of bravery, a bead of sweat desperately leaps from a vein popping out of her forehead, but it’s too late. Betty rips a hot one that vaporizes the flailing sweat bead mid-flight and clears out the gallery hall.

On most days, this causes a slight delay in production. When playgoers finally come to, Betty’s full lips spread into a menacing grin, foreshadowing one last offense. Maniacally, she grinds and twists her torso toward the ground until she self-aborts, defecating two small infants into the murky swamp. Her performance weighs a ton. By now, bombastic drums strong-arm their way to the foreground of the symphonic melee.

Lurking above Betty in the open sky, a second young boy with swollen genitals drifts toward the ancestral world. He was the father of Betty’s aborted children, slain by a jealous slave trader when it was discovered Betty was pregnant. In the final scene, an intoxicated slave master wearing a tuxedo jacket sodomizes a house servant in an open field. Ruthlessly, he rips off her dress, lifts her feet high off the ground and forces his tongue up her anus. Her cries are muffled by large chunks of food, choked up in shock.

For her sake and ours, the servant manages to catch her broom before it hits the ground. A moralistic wink from the exhuming playwright.

Intermission

Driver No. 523689 paused at another stop light. Without looking up, I could sense he was eyeing me through the rearview mirror, like a television on mute in the next room. All this shit was an awful game. I rolled my eyes, looked out the window, and caught a glimpse of the sunken schoolyard at the Graffiti Hall of Fame — the site of many boyish first encounters. None more memorable than Tanya Santana, my first kiss and second baptism. Before her I remembered everything; after her I remembered nothing. We dated from the ages “You like me Yes or No” to “Meet me at the make-out spot after school.” We broke up when she got over Jordans and into older guys with gold BBS rims.

One afternoon, during the make-out years, Tanya and I wiped away another practice run from around our mouths, stood hip to hip and stared at each other longingly. There was only so much intimacy you could explore at the make-out spot, and we’d grown tired of having all the jelly but no jam. We inherited the area from generations of horny kids who chose it because it had good site lines to spot intruders and an escape route that led to the courtyard at Lehman Houses. With only about an hour to spare after school, our bodies would fidget like moths in light because before long a neighborhood auntie type would walk by and say, “Uh-uh, y’all too young to be acting so fresh!” That day, Tanya and I stopped before things got so fresh. What was understood didn’t need to be said. To behold the promise of a better tomorrow, we would have to go our separate ways and take matters into our own hands.

When it came to masturbation, I understood the basic mechanics of the situation but could never quite finish the job. Like a journeyman boxer who can never shake the recurring nightmare of almost making it to the top. What if he had trained a little harder? What if he didn’t get in that car?

The scene played out like the first act of every coming-of-age movie ever made. To set the mood, I would roll my head back, close my eyes, and imagine Tanya, spotlit, cascading down the school hall. Born Dominican with a Mexican Coke bottle body, Tanya was America’s adolescent wet dream, and in my dreams, nothing came into being until she opened her eyes. When she did, always in slow motion, she’d stare like an iceberg grills at a passing ship, then coolly look away. With each step I’d inch further and further into the peep-show valleys of my mind, affectionately admiring the dress her mother wouldn’t let her wear out the house, struggling to hold it all together. Then, nothing — emptiness. Like dice tossed at a wall in a haunted house, disappearing into the next room. No embarrassment overrun by wanton satisfaction moisturizing the corners of my mouth. No pins and needles traveling down my spine to the tips of my toes. No reaching over for a Kleenex to cover my tracks.

It was 1996 when the mission was complete, and, like a French fry, I felt like an American hero. The world was between things. Millennials, gassed by their “world is your oyster” Boomer parents, had one eye nodding off to an episode of Gen X’s The Real World while the other wandered the computer-generated moral side streets of the society of the future — picking through the trash to find Black Squares Gen Z hadn’t posted yet. Rap music was between East and West. Tragically, Tupac would lose his life in that battle (and from time to time miraculously return from the dead) just as his legion of followers were starting to mouth the words to “How do You Want It,” a pimped-out B-side that followed a summer of keeping the rent paid on the A-side “California Love.”

After losing enough dice to haunted walls, I’d discover getting off was all in the details, and when it came to porn, I was inspired by a good story. It makes all the difference when I’m aware of the exact sequence of events that led to Adriana Chechik being hogtied and soaked in baby oil by a strap-on toting Kira Noir. Is Adriana an incompetent accountant being punished for filing Kira’s taxes too late? Or are they Russian spies and Adriana is being slavishly rewarded for keeping her mouth shut when local authorities brought her in for questioning about a secret plot to overthrow the government?

Before Adriana and Kira, though, there was Dee Baker, aka Lady Dee, starring in canonical, straight to DVD titles such as Dee is Devine, produced by Afro-Centric Productions. Dee was from a time before the Brazzerfication of porn, tucked somewhere between the campy kinks of Robin Byrd’s couch and a few rows down from the fatalistic melodramas on Skinamax. I can’t remember the title or exact sequence of events that played out while watching the film Dee was starring in, but I do remember the demoralizing atmosphere. Ball players, rappers, and video vixens enshrined on my walls put their heads in their hands and looked away. I would usually be more relaxed around Dee, but that night — like a mutant with the power to see through walls — I watched her with grit and determination. Goal oriented, I yanked and yanked away, mouthing a pathetic apology to Tanya until, finally, I broke through.

Joan Didion said somewhere that innocence ends when one is stripped of the delusion that one likes oneself. Probably, but summer in New York will always be better when there’s rap beef.

Act 3 – No Photos Please

Betty grabbed a handful of oak leaves scattered at the foot of the marshy hill, careful not to disturb Nan, who was fellating the master’s son up above. Satisfied, she knelt to organize them into a pile then crouched down on the balls of her feet. Looking away, she clamped the hemline of her skirt between her teeth and pulled her underwear down to her ankles. Without looking, she reached down to pick up the pile of leaves when suddenly a guttural sound from above made her jump back. The master’s son had climaxed. Disgusted, Betty sucked her teeth and muttered under her breath toward the hill. She hated that scene.

Leaves still in hand, Betty thrust them up her ass to wipe away the remains of defecated fetuses. Satisfied, she tossed the bloody leaves into the swamp, and stared as they eerily crept across the murky surface — carving an amorphous hole through the algae. Looking past her reflection, Betty could see a tomb of fetuses from past shows nestled at the bottom of the swamp, one stacked on top of the other. She swallowed the vomit in her throat.

“Hey Nan, I’s punchin out fa da day. If Kara come round lookin fo me tella I be back tomorruh.”

Nan was resting on her knees, back toward Betty, wiping the master’s son’s cum off her face. “So I gots to suck dis boy lil dick all day and be yo messenger?”

Betty, looking up at Nan, “You sure do have a whore’s mouf on you. I tol you I’d bring some of that catfish from Amy Ruth’s you love so much.” “You had better!” Nan said. “What you fixin to do anyway?”

“Will got me goin to a show downtown, somethin bout enfant terribles.”

“E-fon-terra who?”

“Never mind, see you tomorruh.”

Betty peered out into the packed gallery and scanned the room terminator-style. She needed an escape route. The usual suspects were in attendance. Sport jackets huddled together in academic discourse. First-generation phones, soon to be unemployed by the iPhone, snapping third-world selfies. Upturned noses of late-career Black artists who came to pass judgment, and the stale whiff of weed looming over that one security guard who can’t wait to let you know that he knows everything there is to know about the show. “Yeeaah, that’s one of her early joints right there but she don’t really fuck with color like that no more. No photos please.”

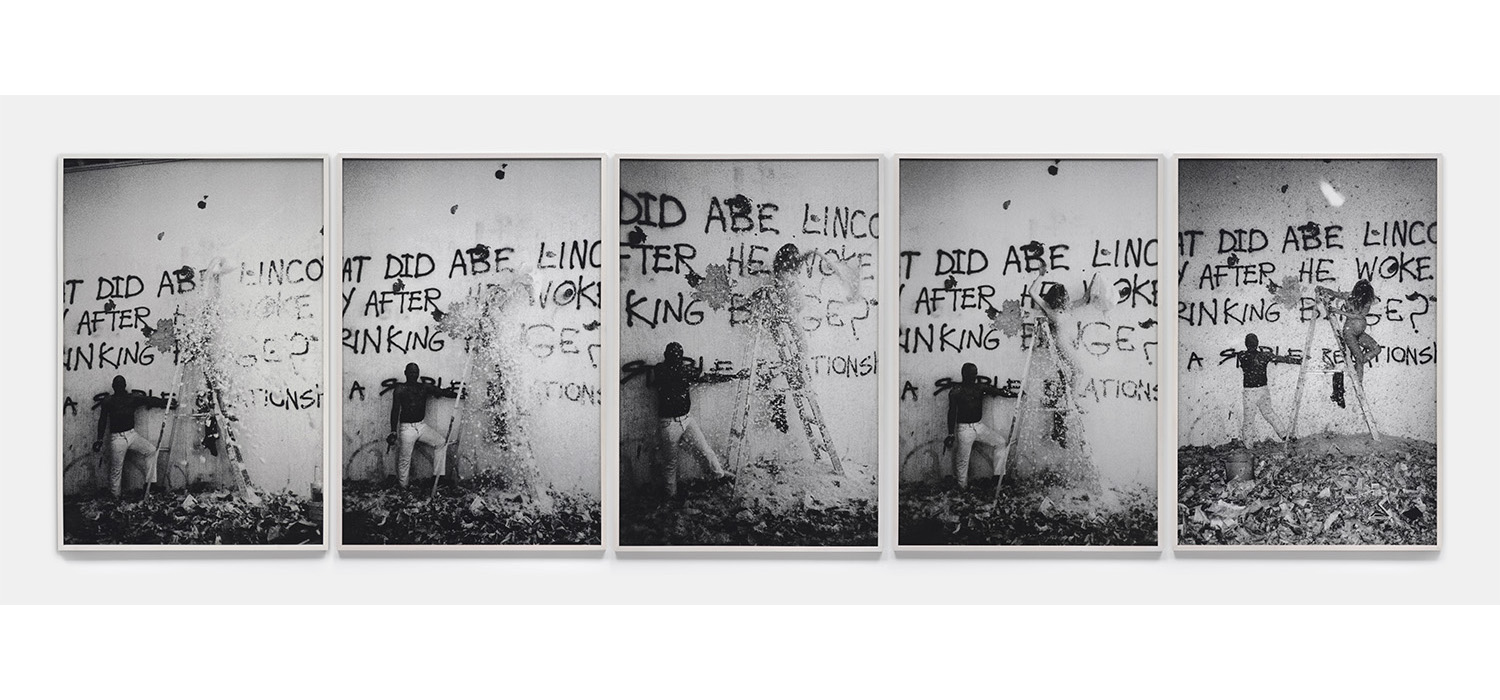

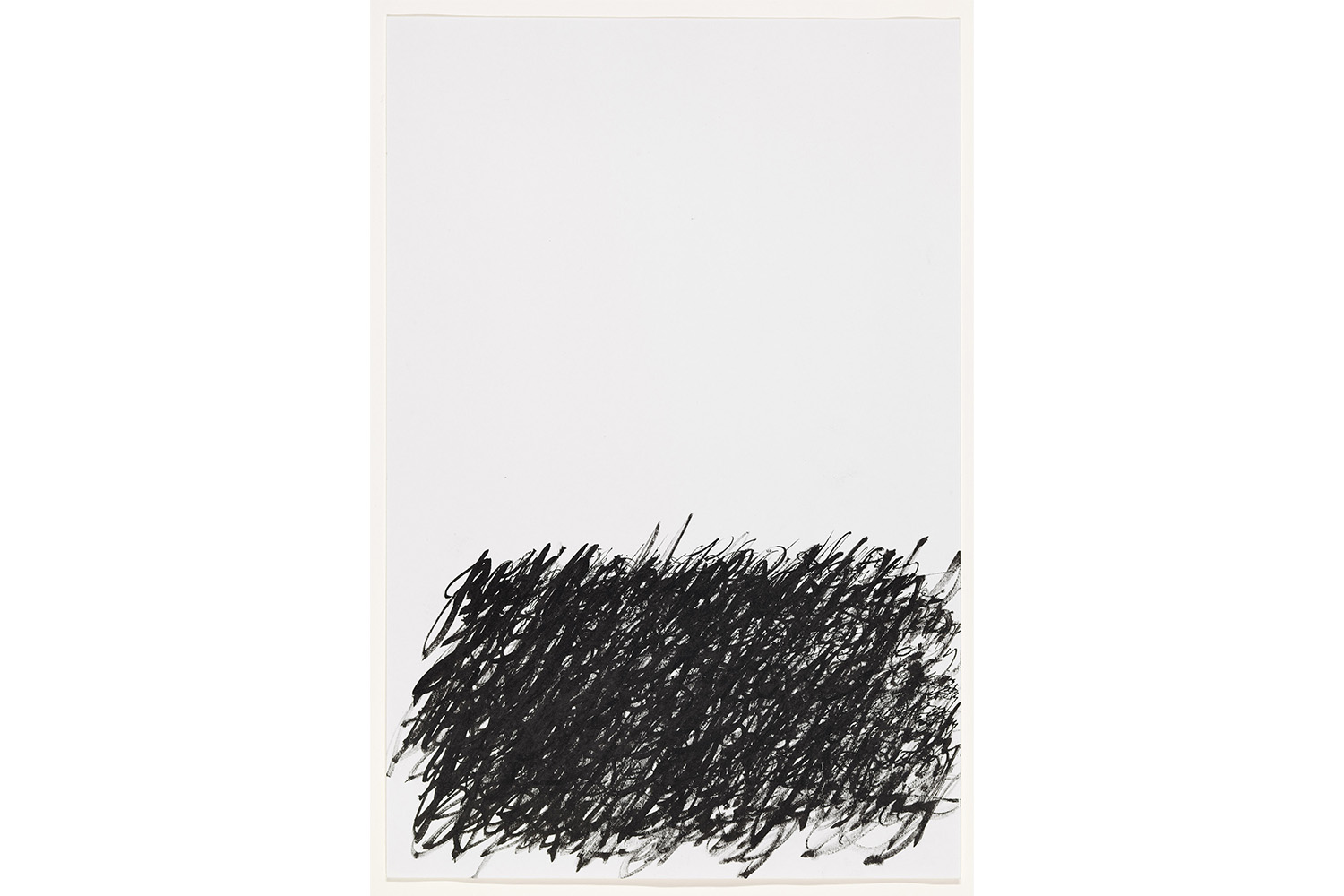

Finally, Betty spotted an opening between a narcissist sport coat and a washed-up Motorola Razr. Sneakily, she peeled her languid body off the wall, limb by limb, and leapt from Walker’s tableau. She hit the ground, tucked her chin into her shoulder, poked her elbows out and speed waddled through the crowd with a runaway’s ambition. Toes were stomped, baby carriages hurdled over, mean mugs requesting autographs shot down. She muscled her way between Roberta Smith and Jerry Saltz marinating on Walker’s re-writing Black History, 400 years of bondage, 25 years of Boredom (1994) and spun away from Hilton Als’s outstretched hand beckoning to Kiki about racial profiling in America.

Luck on her side, she made a clean getaway. No tea spilled about her alleged, off-camera interracial romance with the slave master that stars in Kara Walker’s Grub for Sharks: A Concession to the Negro Populace (2004). Or the beef between Betye Saar and Walker that spilled over into a shouting match at the Japanese restaurant, Omen, a few weeks ago. No mess about her method style of acting and the lasting psychological effects of playing a slave.

Outside, Betty stepped in front of the low concrete canopy at the entrance of the Whitney and let the sun wash over. At first, her limp silhouette swayed then wilted into the arms of a passing breeze. Soundlessly, she closed her eyes, pressed her lips to the sky and blew a kiss. When she looked down, she saw Will, shoulders shrugged, hanging out the back-seat window of a yellow cab. She paid him no mind, tilted her head back to the sky, and made him wait.