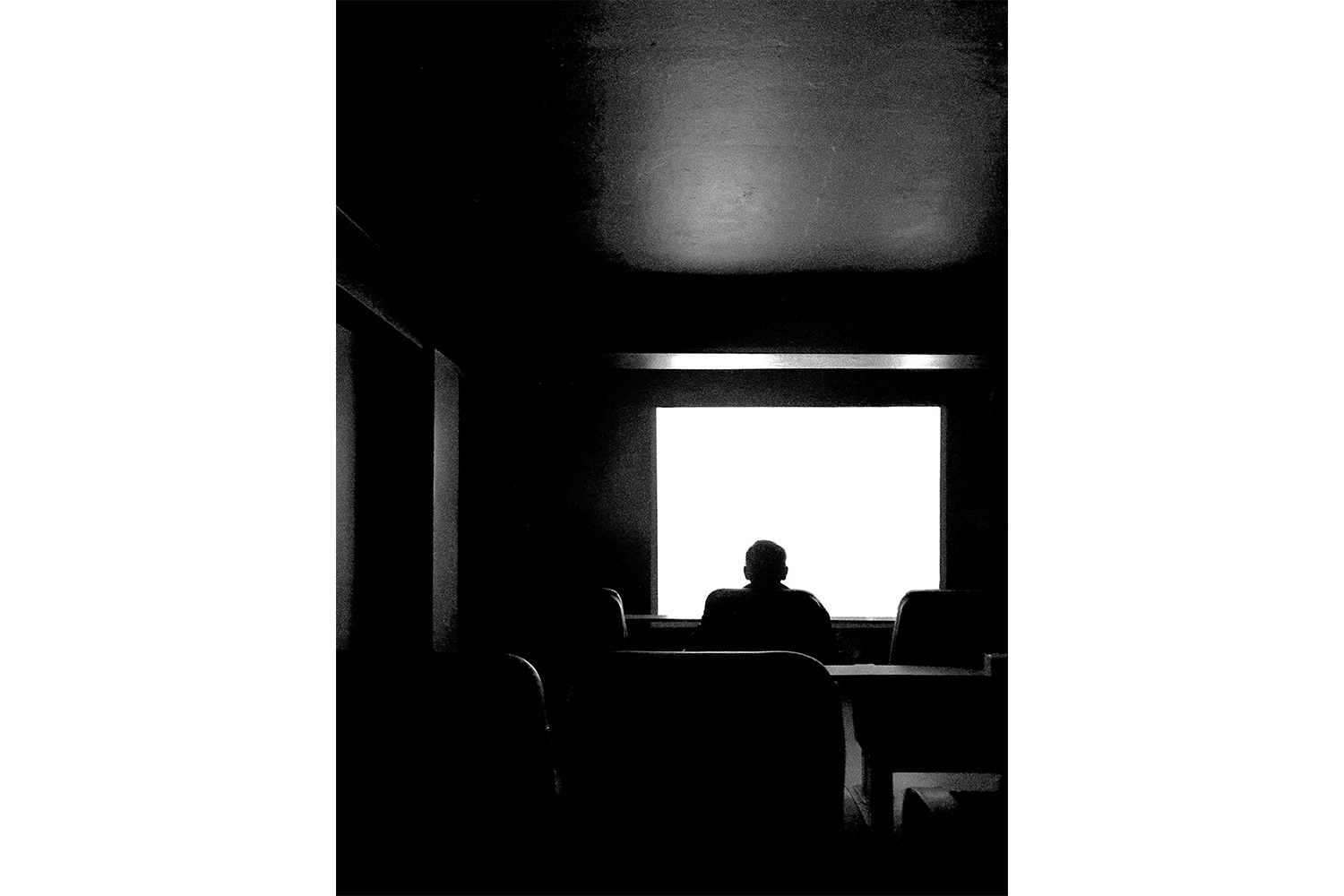

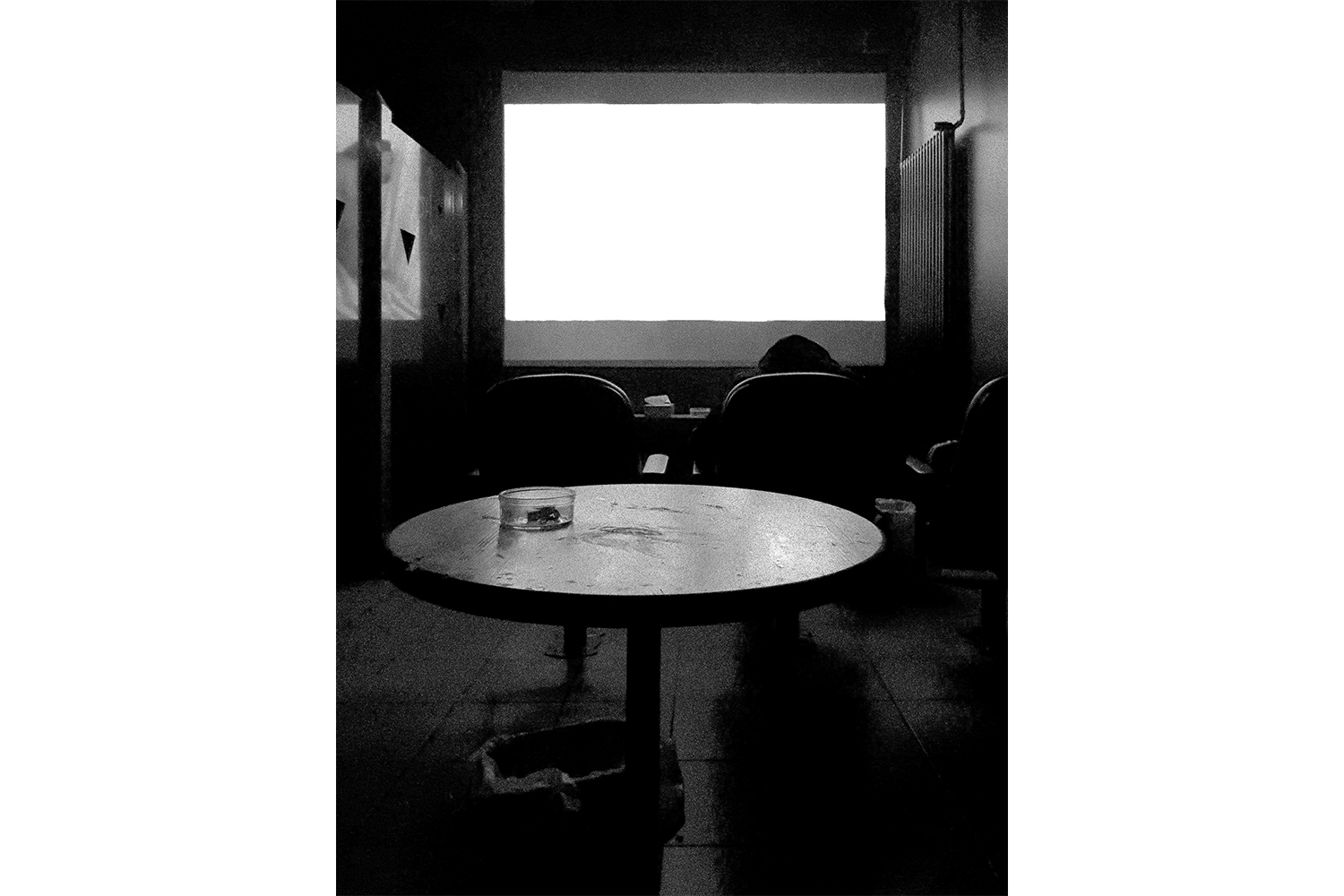

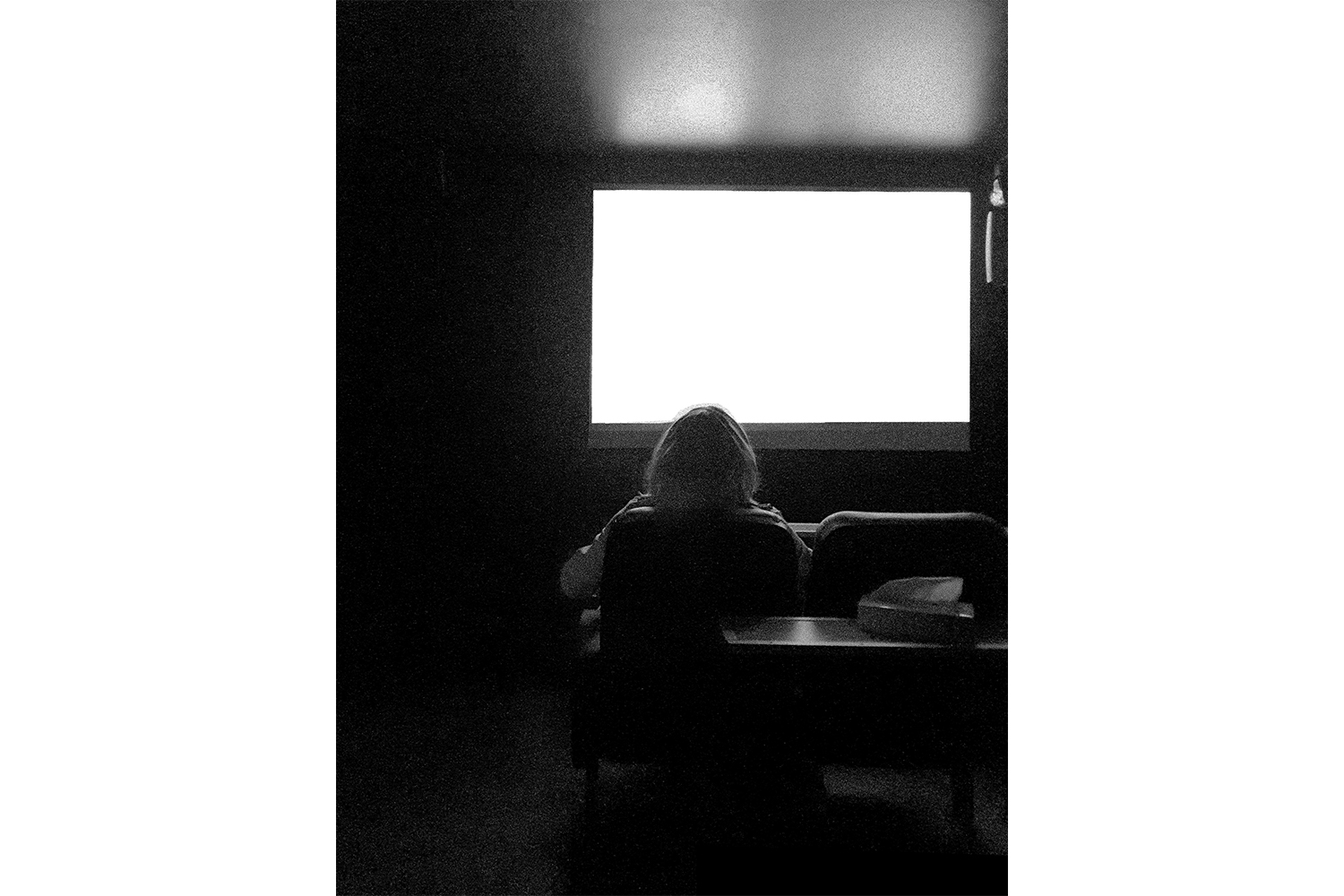

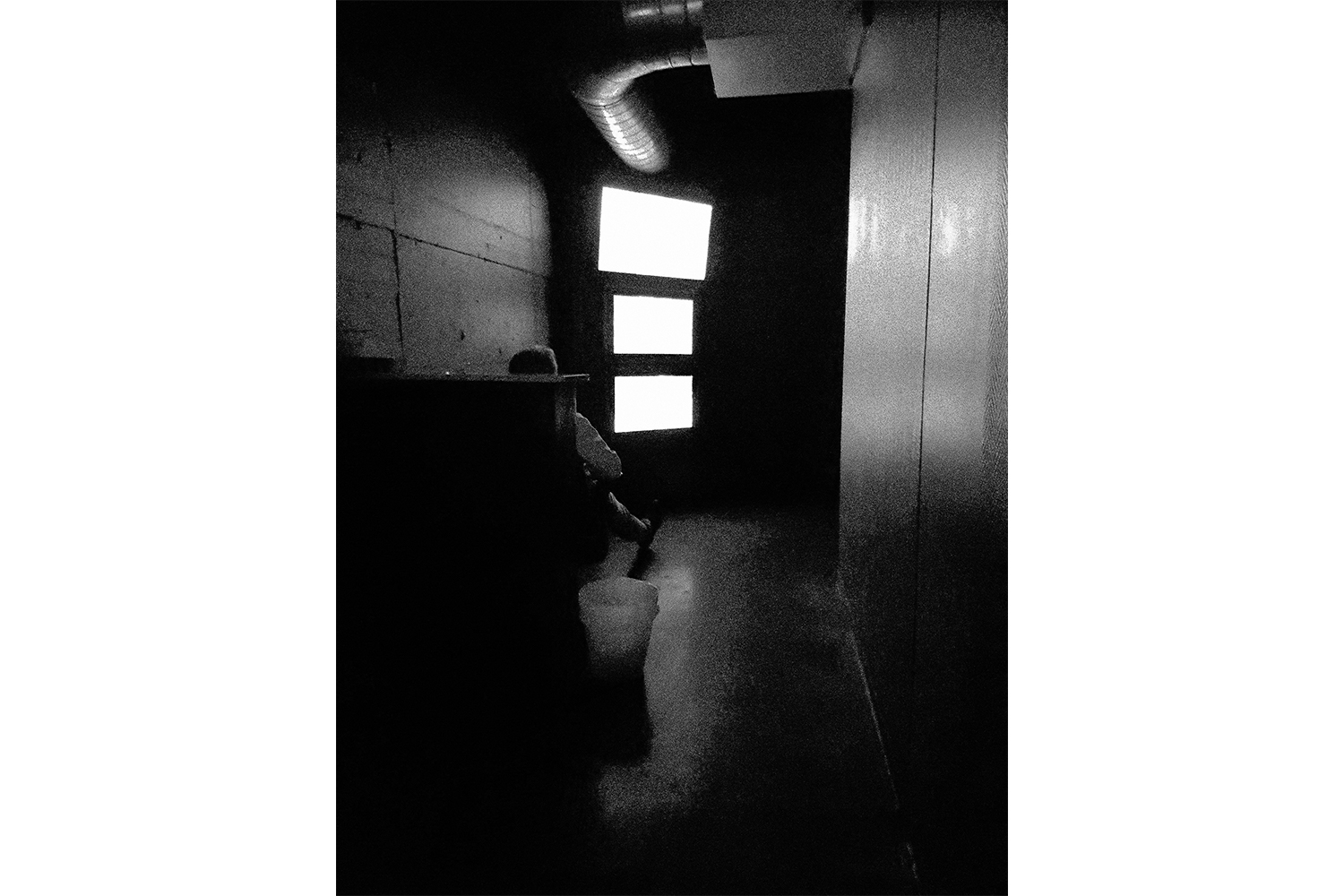

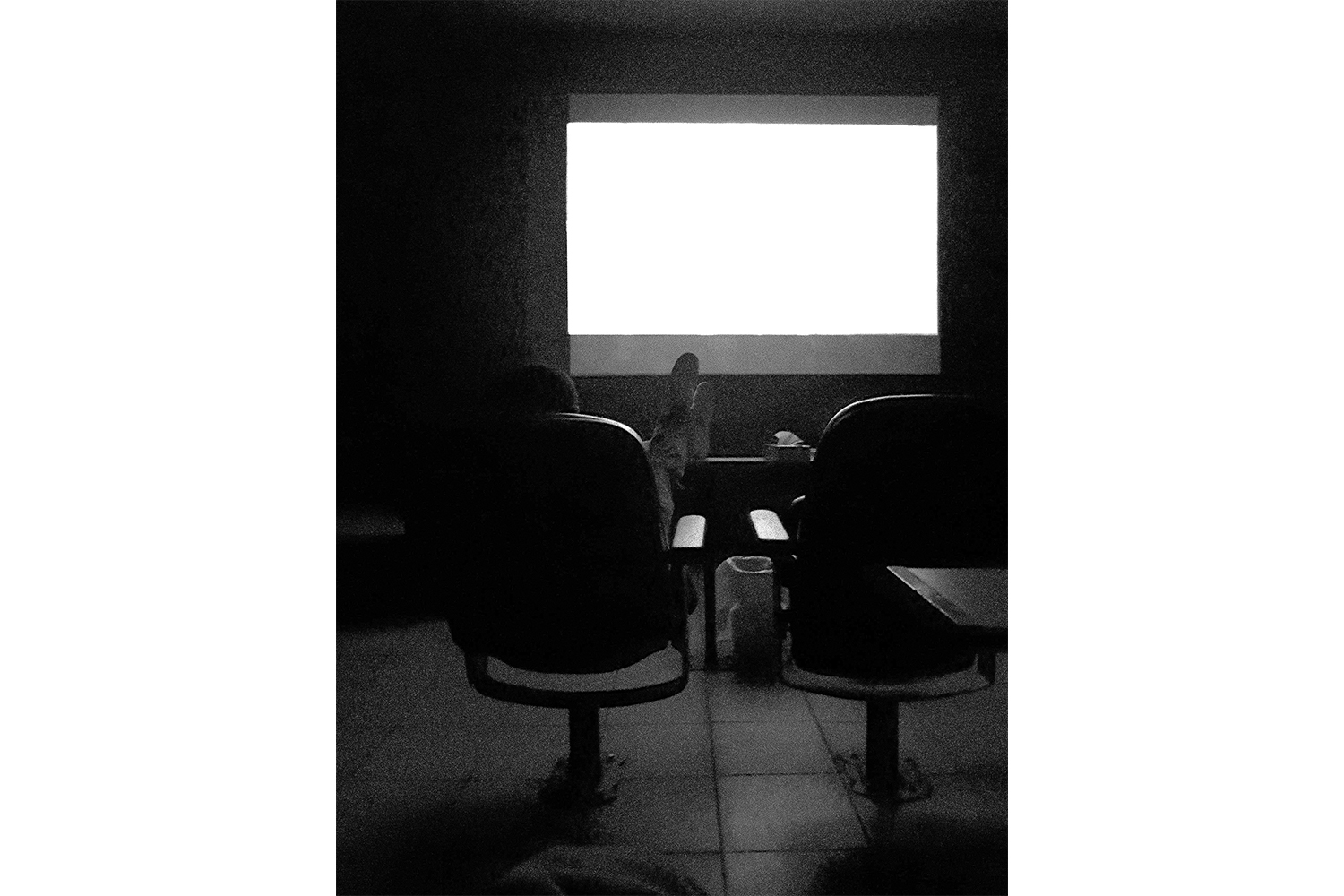

In Dean Sameshima’s photographs on view at O-Town House, taken covertly in adult movie theaters in Berlin, there is rarely more than one figure in the frame. Silhouettes of theatergoers’ heads are in the foreground; the screen is washed out; no projected image is visible. In images there’s a wastebasket, boxes of tissues, ashtrays, but one’s eye is drawn to the white screen, the glowing void. The long-exposure, high-contrast black-and-white photos show different angles from the back of the theater looking toward the screen, sometimes peeking around the corner, part of the view obstructed by a wall or another body. The show is called “being alone,” but the loneliness is false: the photographer is present even if the person in the audience doesn’t know it. What is it to be alone among others? What does it mean to be alone in public?

Unlike the photographer and audience members who are comforted by the presence of an image, we, the viewers, have nothing to jerk off to. The viewer becomes as alone as the photographer and the moviegoer; we’re all looking at the same screen, but each at a different level of remove.

As a meditation on the precarity of a quasi-social space that is slowly disappearing or being rendered obsolete, this elegant, quiet work has a melancholic tone. The tactility of the photographic prints is emphasized by their being framed without glazing. Exposure to the light coming through the window of the gallery will change them; the prints will become documents of the time spent on exhibit in this place. The graininess of the long exposures makes the blacks look almost like graphite, with an inky opacity. Like the spaces they depict, the photographs themselves are endangered. With exposure to light, like the activities carried out in a porn theater, the photographs will change.

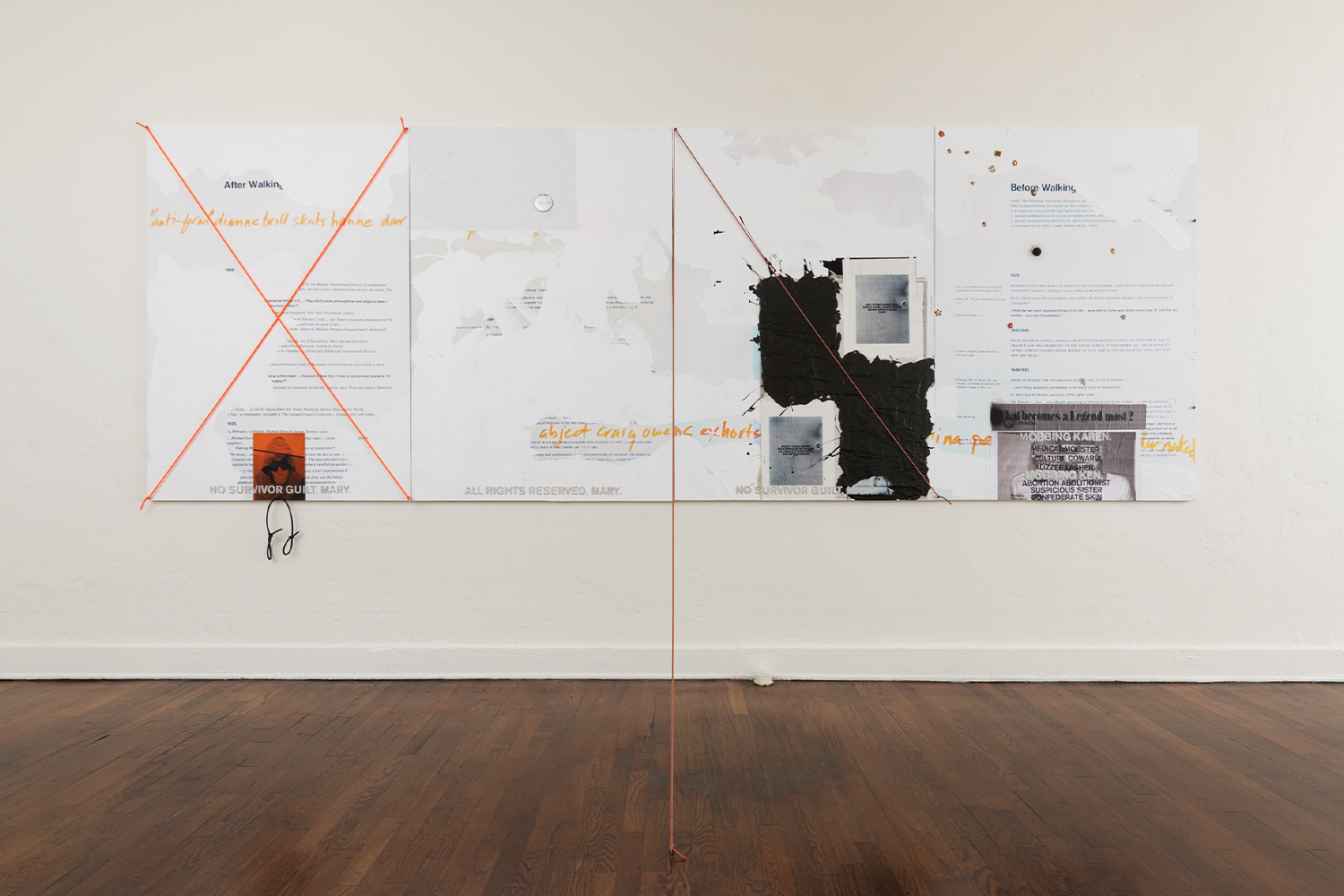

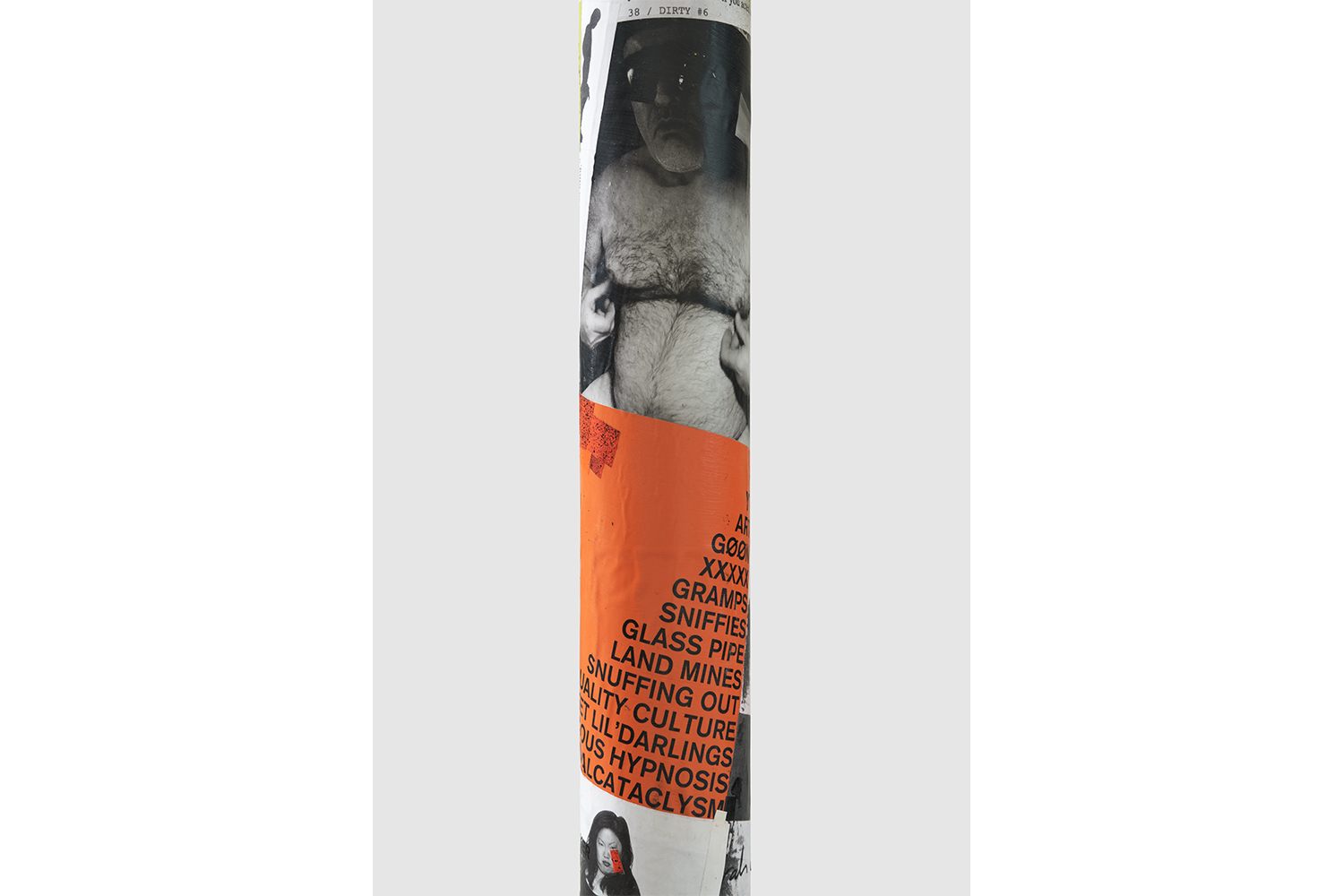

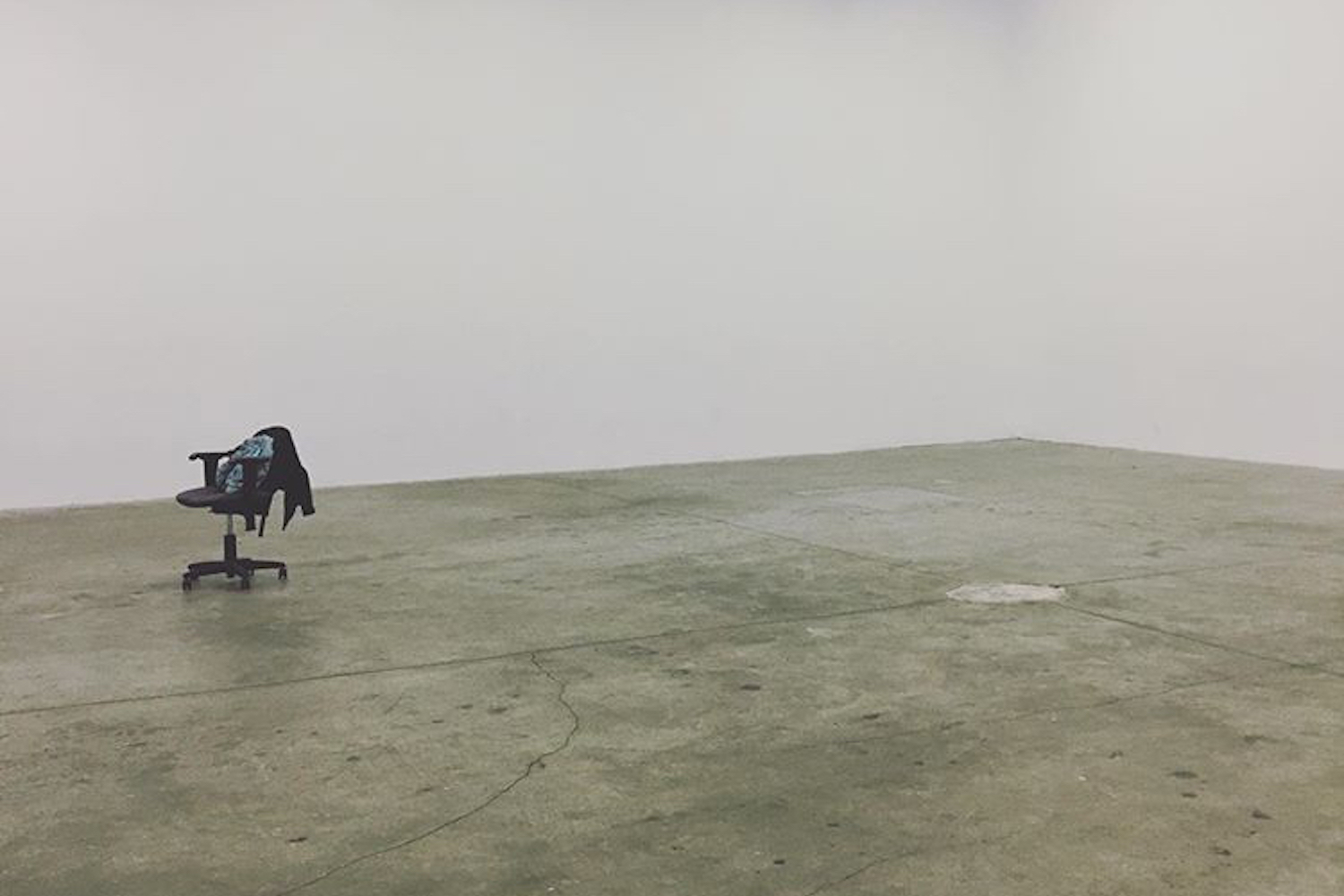

If Sameshima’s work sounds like quiet whispers or shuffling in a movie theater, Verabioff’s sounds like nonsense shouted in a bar with music bumping. The works deliver what is teased in the exhibition’s title: verbiage. The canvasses, despite being highly saturated with text and image, begin trains of thought that lead to nowhere. He provides a smattering of seemingly unrelated references, leaving you to construct meaning yourself: Michael Snow’s biography; chewed gum that resembles lesions; self-portraits of the artist; hot guys on Instagram; a letter from the 1980s with the artist’s New York address. Cheeky deceptions literally jump out from the paintings: rubber wires extend from surfaces like booby traps, as if to literally trip up the viewer. One wire coming from CCCP (CUM CURSE CASTIGATOR PECKER) (2023) is taut enough to ensure a quick, clean trip, whereas a length of limp tubing further on might create more of an inelegant slow stumble, ensnaring the viewer in tangle of rubber on the gallery floor.

Upon entering the gallery, one is confronted with a pole a bit taller than the average viewer. The obstruction, like a traffic signal, confirms the artist’s eagerness to draw you in, to make you pay attention.

Both shows exude a kind of nostalgia, but not a cheap retro one. Both artists are gay men of a certain age who lived through the AIDS crisis, and their works reflect on a kind of gay cultural history that has transitioned from the extant to the archival. While some spaces are truly lost, others are merely outdated. As homosexuality is integrated into the mainstream and digital platforms take over, cultural spaces like bars and adult movie theaters, once a haven for transgression, are no longer in demand. They begin to enter a liminal zone of sentimentality. Both artists, who collaborated on a zine for the exhibition, push back against this idea; they refuse to fade into obscurity. As Verabioff, quoted in the press release, asserts: “Attention children: don’t think Gramps is one of those lame-ass-neo-sniffies-libs-bitter-basic-cis-twit male painters!” Gramps certainly is not.