“X” speaks of cryptic notice: a point slyly declarative and deliberately obscuring. Beyond codification, “X” is a teasing mark of secrecy that evokes in its erasure supposed excess, a denotation of this, here, while alleged content remains tantalizingly unknown. It is an intriguing tactic for introducing the work of Norwegian American artist Robert Rasmussen — who, since 1967, has worked under the alias Redd Ekks — in his first solo exhibition in more than twenty years. The pseudonym eagerly invests in the materiality of language and symbolist potential, suggesting esoteric self-articulation through surrealist artifice and doses of mysticism. As an exhibition, “X,” curated by Zully Adler, is less indexical closure than an intersection of attracted divergences, an impulse which his sculptures readily infer: summoning prelinguistic, syncretic plenitude through inscrutable forms that are both vault and armature; trove and fulcrum; lock and key.

After graduating from the San Francisco Art Institute in 1959, Redd Ekks continued to teach at the school’s ceramics program alongside Ron Nagle and Richard Shaw. While California’s ceramic arts movement expanded the treatments of clay as sculptural property and medium, Ekks’s work is distinguished for its use of scale, volume, and surface, each alchemised to an extent that they queer and convolute one another, uncertain as to what should be observable and what should remain coiled and cossetted in his lithic caverns. Despite the material obduracy of his ceramics, viewers scrutinise their quiddities, peeling them petallike to achieve the final kernel of their force. It is a fated flummoxing that returns the viewer and work to a sense of remote inertia, lavishing an absolute center that never arrives.

The ribbed, marmoreal casing of Molen II (1989) reveals in its recess a nested kidney-shaped hatchling, permanently pupal. Suspended in its corrugated, conifer green grotto and sluiced brown, it is indelibly adjourned to something unborn and potentially wanting-to-be. Or is it wilfully eremitic? Destined and errantly detained as pure exception, a divine anomaly? Attar II (2003) is ranine and runic; in tree frog green its monocular vision features a downturned beak and undulant volume writ with cursive: “With diverse properties he endowed the net of the body, and he has put dust on the tail of the bird of the soul.” The quote derives from The Conference of Birds by the medieval Persian poet Farid ud-Din Attar, an epic spiritual allegory on the pursuit of Sufism that culminates in the divine encounter of truth from within, signified by Simorgh, a winged creature of mystical enlightenment. Encircling Attar II, the form unfurls itself; a plump mercury teardrop is suspended with perishing drama above a forked emblem, the liquid pendant evoking the nourishing tear of Simorgh. The work is crowned by a tiered cylinder with a glassy bead at its summit like a scrying marble or an accident of guttation. Mr. Salmon (2005) peacocks at full display in the gallery’s window. Nine panels of gauzy plumage in desiccated salmon skin radiate like the crest of a secretary bird. With cavernous eyeholes, darkling glazes, and dorsal curves, it suggests the intermediary artifice of ritualistic stewardship.

Redd Ekks’s works orbit themselves, continuously furrowed and folding in, their morphology conjuring something else as it spirals, their medium as metaphor. Nabokov writes of such liberation: “The spiral is a spiritualised circle. In the spiral form, the circle, uncoiled, unwound, has ceased to be vicious; it has been set free.” There is the affinity, too, of Wallace Stevens’s blackbirds: “Among twenty snowy mountains, / The only moving thing / Was the eye of the blackbird.” The plasmatic qualities of clay freewheel into labile things of alien naturalia, yet Ekks’s control and flourishing trickery induces a persuasive, aberrant logic to each piece. Parasitical blooms the bloodied wound of Suite Georgia (2013–14), whose gory, ophidian ligament is borne from inside, causing a rupture that might be integral to the form’s constrained chaos.

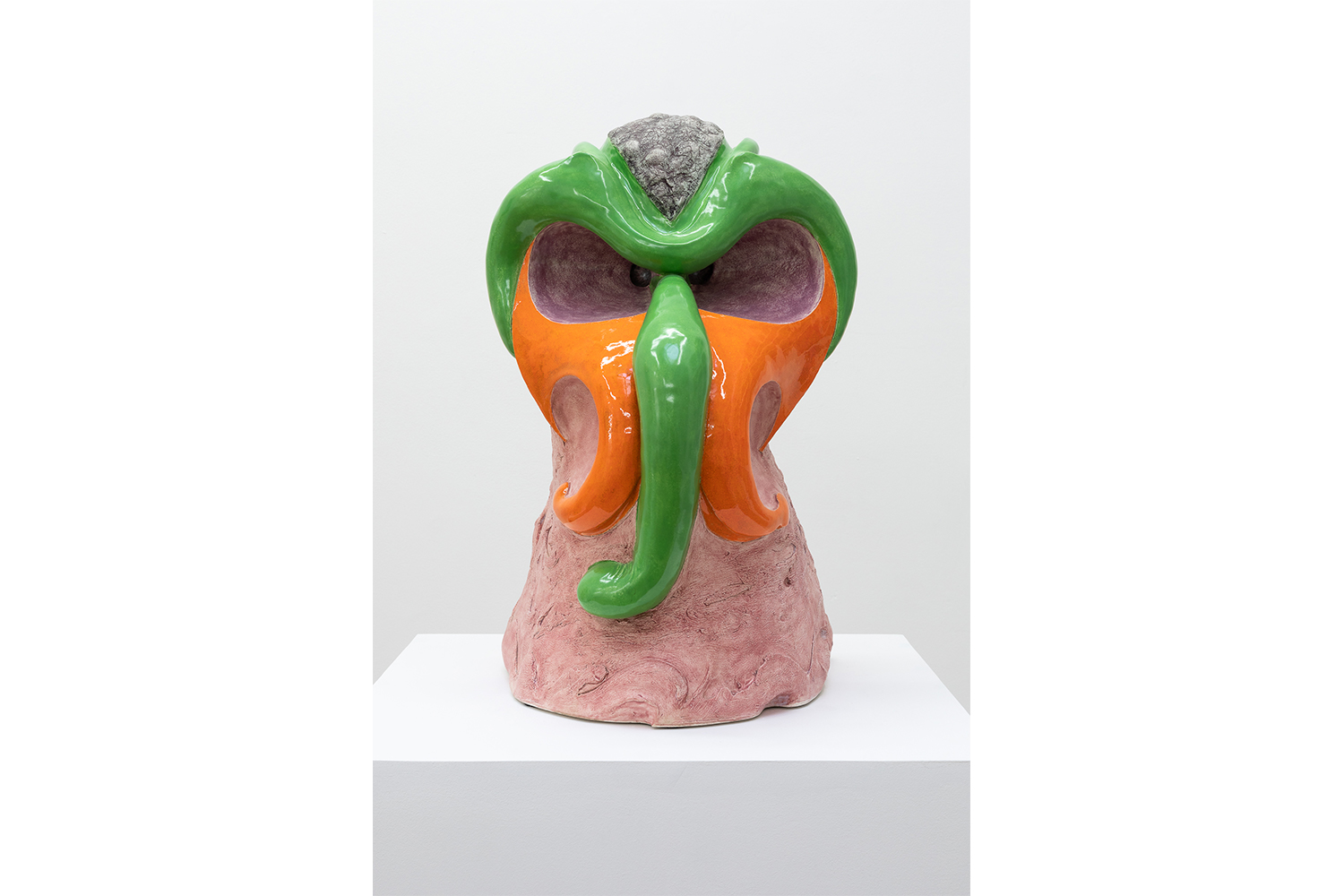

Such display is tempered by an investment in the hidden and sequestered, implied through the architectural confection of inlets and apertures. Attention to the “head” of several sculptures implies a sense of ceremonial, primordial encryption: mesmeric exercises in luring fascination. See the puzzling phantasm of interlocking hexagons in 1i (2007), the flaring compound eyes of Spring (2009), the hammerhead symmetry, vulval folds, and magma glaze of the bubblingly alliterative Takes Two To Tango (2006). In a way, these are faces — portals which flickeringly express and frequently veil; the human face, writes Giorgio Agamben, is “the very opening in which [humans] hide and stay hidden.” Perhaps this is what Redd Ekks recognizes in his aquiline Portrait (1990), with the roof of its cranium engraved with a teddy bear insignia.

While “X” is accompanied by select abstract paintings and architectural studies of proscenium gateways for ancient stones (with curious punning throughout), the ceramics most effectively address the inherent malformation of interior and exterior by invoking mythopoeic qualities and devotional rites, limned through polymorphic symbology. Atavistic urns; solemn guardians; biomorphic lodestones: each transfuses states, climates, and natural signs to some restorative preservation, thick with dormancy. But if these sculptures reserve an ultimately unplaceable stoicism, they communicate as tangential junctures or warped entities to both geography and place with leeching stillness. As Adler writes in the accompanying text, their making is “a ceremony that commemorates the ceremonies of others.” Echo chambers, they speak to the rituals, mythos, and lands which they convoke and decant. As a ruinous folly’s evanescing inflection, the “X” these freestanding totems might purport to place is but a condensation of other temporalities and mysticisms.

Priest (1991) is the most unadorned work. Its shrouded, slouched form tentatively curls into a charred, sapless tree. Ascetic and enigmatic, the elliptical eeriness of Redd Ekks’s work only shows itself through the chimera of creation itself, extant with creaturely drive. Yet in his impervious offerings of mute intensity, they could be a metonym less for ancient sites or mythic allegories than for a subject who revels in looking’s wanting decipherment and fallible spiralling.