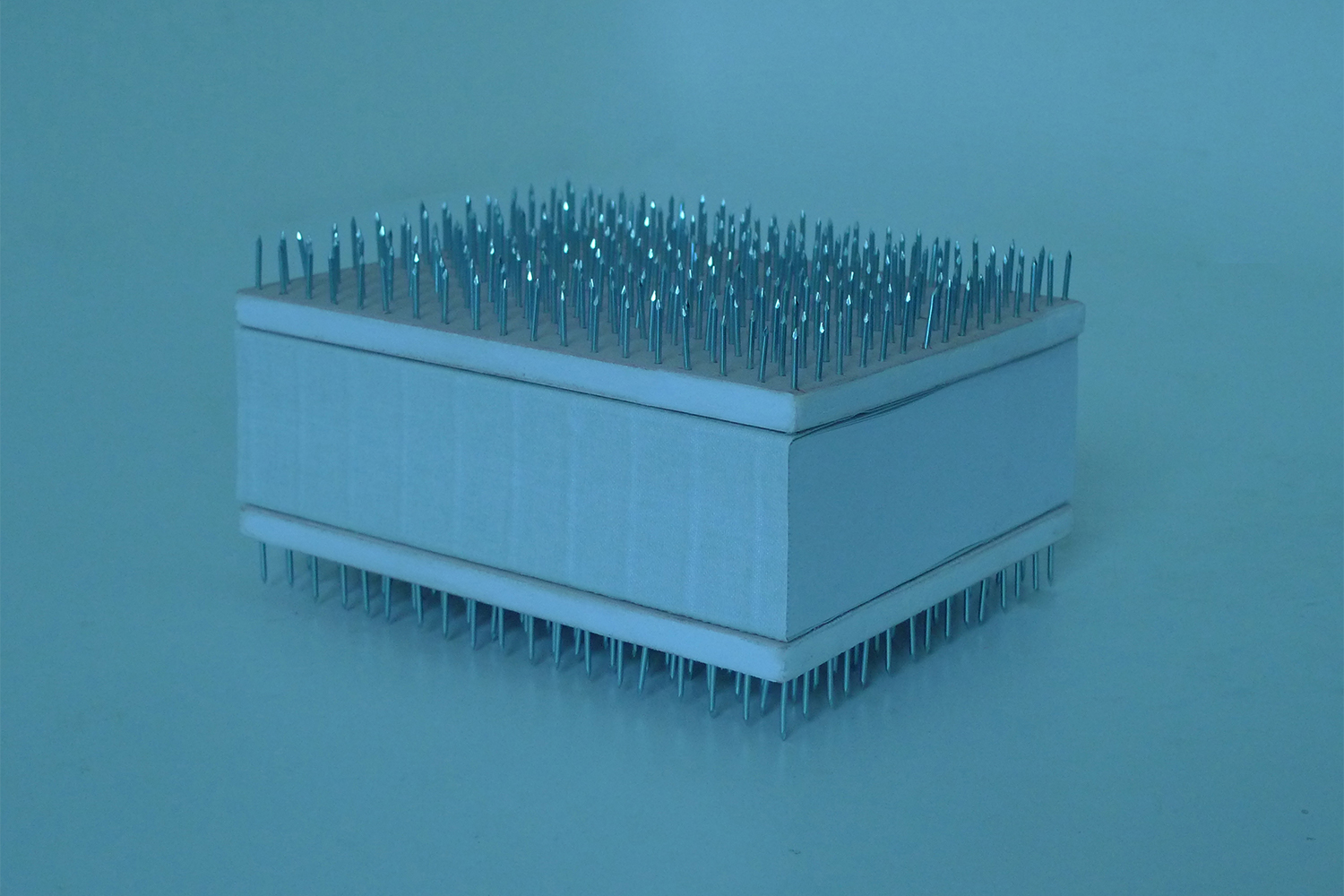

Upon entering Carlota Guerrero’s exhibition “Registro 6: Manglar,” curated by Mariona Valdés, in Paris, visitors are asked to remove their shoes and walk on a “carpet” made of nails. Positioned between two screens that face each other, Organised Pain (2023) serves as a viewing platform for the two videos that give the exhibition its title. The installation is deliberately designed to set a very specific, physical, and piercing welcome. It provokes unease — almost physical pain — in those viewing the films. “When I was creating these pieces, I felt a sense of pain and discomfort. So did most of the girls that worked with me, as we overcame our fears or exposed our vulnerability.” The artist continues, “I often see myself creating beautiful images that come from dark places, which can result in a misreading from the public. This time, I wanted to be quite literal about what’s behind it.” Although Guerrero’s work typically revolves around images imbued with performative experience, the result is often two-dimensional. In this instance though, the three distinct works in the exhibition featuring nails are a reminder perhaps that the quest for vulnerability — whether personal or artistic — is never comfortable or painless.

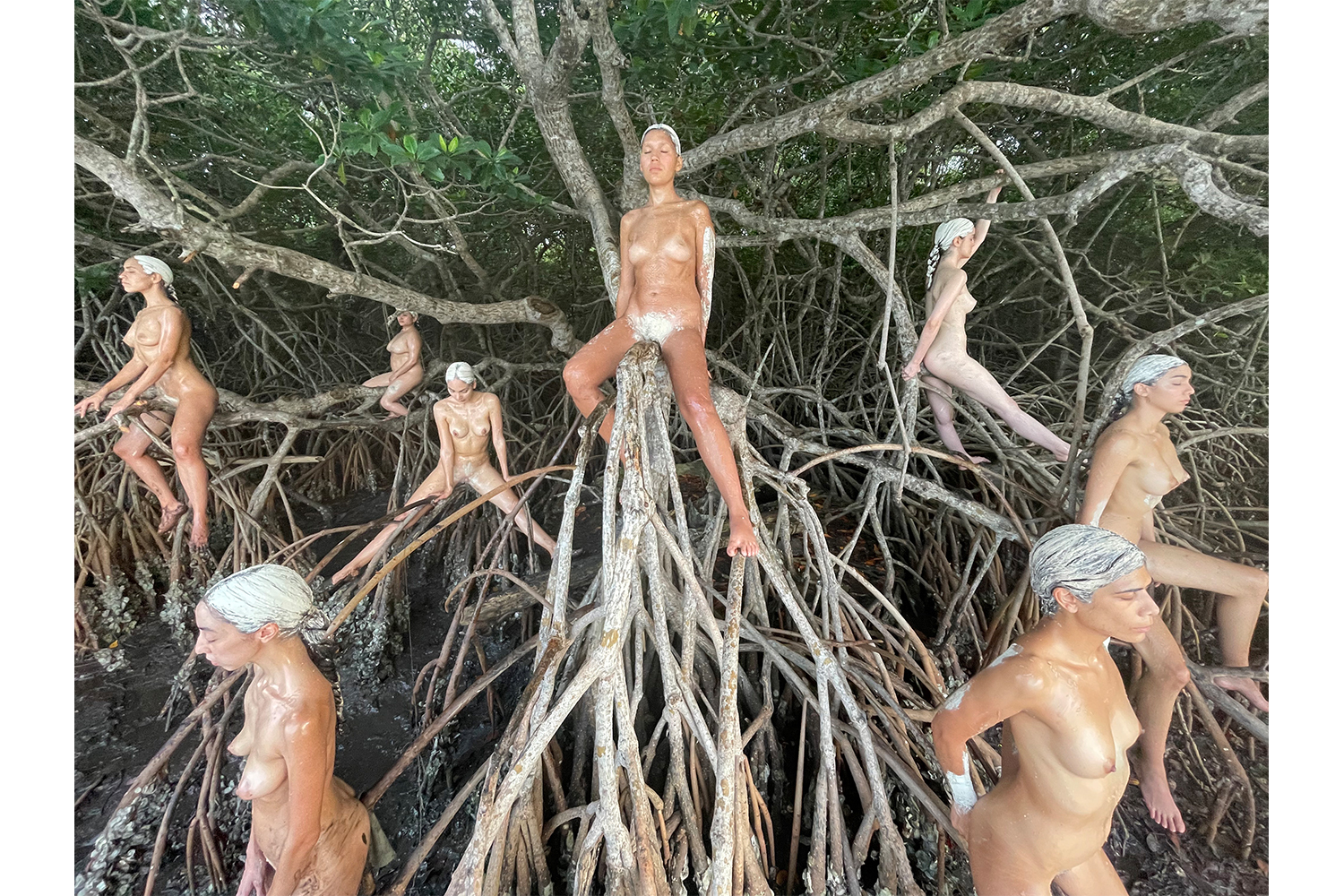

Filmed in a natural reserve of mangroves in Veracruz, México, on August 2021, “Registro 6: Manglar” portrays on one screen the ritualistic experience of a group of eight women amid the mangroves on a river. The opposite screen depicts the individual experience of Carmen, set in a neutral and contemporary interior space. The two scenes have in common a central image of a giant “communal clitoris” made of mangrove branches. This natural totem, in which Guerrero recognized a metaphorical representation of a clitoris, guides the bodies of Samai, Camila, Nika, Monse, Valeria, Sarahí, Fernanda, GG, and Carmen as they navigate the orchestrated ritual toward the “center of the earth.”

In 1973, Ana Mendieta started her “Silueta” series. She used the silhouette of her own body to create performances, videos, and photographs in an attempt to deepen her research into the relationship between the female body, nature, and spirituality. In a letter to art historian and curator John Perreault, she wrote: “I have been carrying on a dialogue between the landscape and the female body (based on my own silhouette). […] I am overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast from the womb (nature). My art is the way I reestablish the bonds that unite me to the universe.” In 1974, feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray published the book Speculum of the Other Woman, arguing that through a dualistic system constructed by Western philosophy, women have been repeatedly excluded from the realm of reason, culture, and objectivity, and have been associated with (subdued) nature, subjectivity, and matter through different forms of historical and artistic representation. Fifty years later — in a moment in which the female body is far from being emancipated from patriarchal domination and male narratives — Guerrero expands on that same complex, multilayered, and overwhelming relationship that links women to nature. In both “Registro 6: Manglar” and in most of her other works, Guerrero proposes an alternative feminine perspective on valuing the world, one that highlights speculative vestiges of matriarchal scenarios and symbolically repairs historical gaps within a collective imagination that has largely been shaped by male experience.

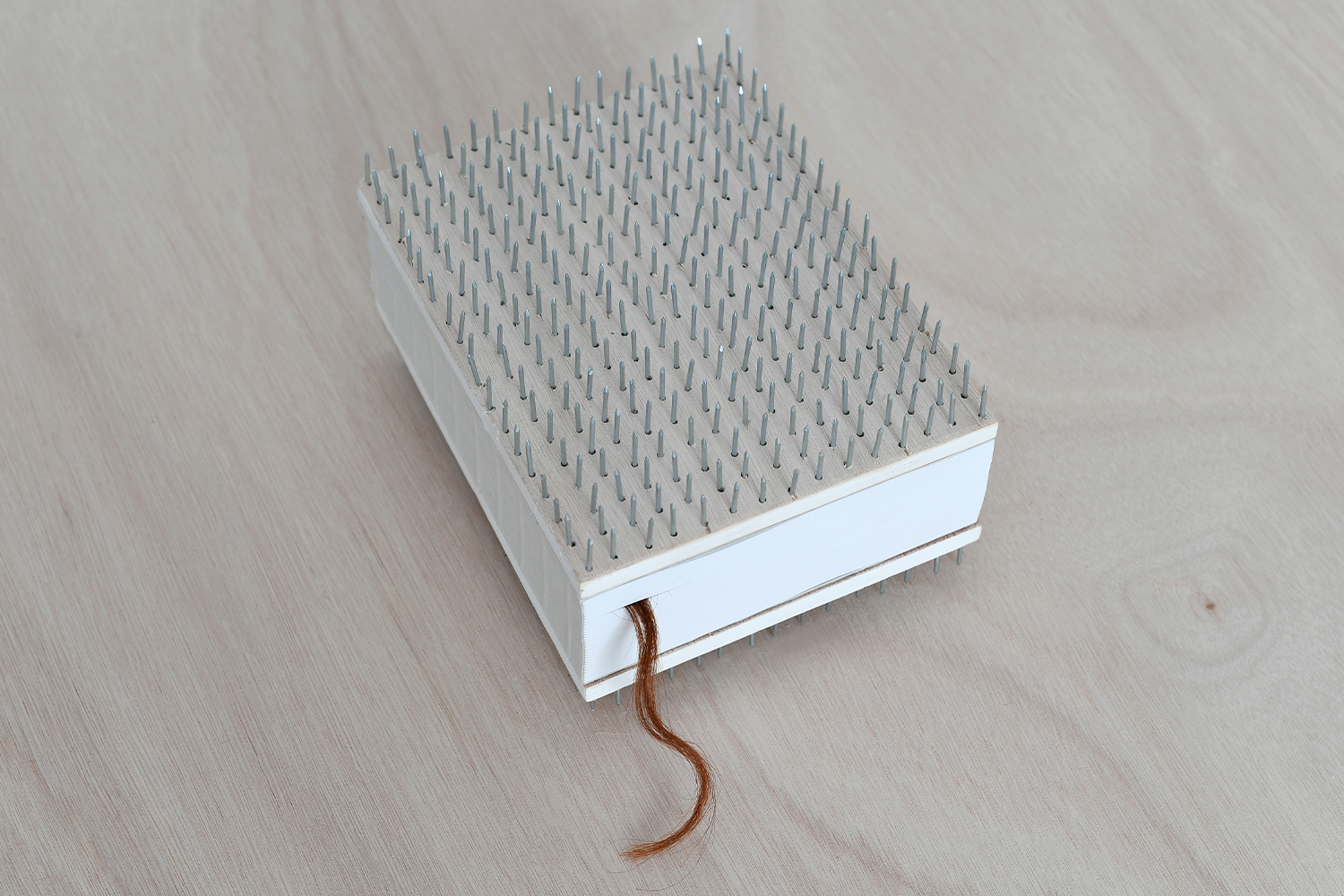

On the second floor of the gallery, two works featuring human hair are displayed, as if to balance out the sharpness of the spiky nails. Human hair is one of Guerrero’s signature materials, which she often deploys in an intuitive and abstract way, as seen in her work Canales (2022). About Raíz (2023) though, she tells a Christmas party story that kickstarted the work. On that occasion, Guerrero started talking to a woman and hair artist named Sonam Solanki. They had both taken LSD, which made the conversation very honest, and they quickly started talking about the things that most mattered to them, including hair. “We were talking about our passion for hair, when this sudden inspiration came to us: it was this woman who had roots coming out of her vagina. It appeared to have so much strength that we spent the night drawing it and discussing each detail of our collaboration. “Raiz is the physical result of that first conversation.”

I have always perceived Guerrero’s work as an encompassing web. Through a variety of instances and forms she braids visual and metaphorical kinships to create a new kind of female communion. While her work isn’t described as autobiographical, her research is as universal as it is intimate, which is perhaps why so many of the women she loves and respects are featured in her work. One, a portrait of Rosalía, one of the artist’s closest friends, is in fact featured in the show. Like tree branches, hair, and social connections, her work maps out a new female iconography that challenges itself and those that came before. It’s through this connection — which oscillates between vulnerability and the regaining of power — that new archetypes, new bonds, and new myths for female unity are formed.