After several years of anxieties, deprivations, and basic fare, it feels as if Paris is back in bloom, offering a vast and maximalist institutional program whose gigantic scale seems have been boosted by the arrival of Paris + par Art Basel, which has come to replace FIAC. It seems the new fair, which is of high quality despite having “only” 156 booths in the Grand Palais Éphémère — a figure that should be closer to 200 in 2024, once work on the historic Grand Palais is completed — has joined forces with several institutions.

This effervescence, rarely taken to such an extreme, part of a programmatic and festive orgy manifested to a certain degree earlier in the year elsewhere in Europe, at Basel in June and in London at the beginning of October during Frieze, seems to have proliferated here, with its form, if not its substance, deliberately forgetting the dark tone of geopolitical, ecological, and political realities, leaving far behind the memory of austerity policies. Alternative fairs, from Paris Internationale to the Bienvenue Art Fair, Asia Now, and AKAA (Also Known as Africa), and programming at artist-run spaces, including the brand new Artagon Pantin and the 66th Salon de Montrouge, reinvented this year by Work Method (Guillaume Désanges and Coline Davenne), formed a dizzying ensemble, threatening saturation despite their quality. It was the same with gallery openings, ranging from the most international to the most local, which are usually more spread out over time. If not for my brief here — to report on institutional exhibitions — I would have liked to give an account of the full breadth of this incredible effervescence. Still, the temptation to add one or two venues may prove irresistible.

This contrast between maximalist exhibitions and other more modest and local but no less ambitious, between gigantism and acts of resistance, is undoubtedly at the crux of the mutation of the Parisian scene. Still, in almost all cases, there remains a balance between content and form that is typically French.

The exhibitions at the Bourse de Commerce are the most obvious example of this double tropism, which is expressed in a paradigmatic way in the monographic exhibition devoted to Anri Sala that closes the cycle “Une seconde d’éternité” curated by Emma Lavigne. The show, of which Caroline Bourgeois is co-curator, is articulated around video works by the artist and reflects both this trend toward monumentality as well as a richness of content — a contrast or double bind that is typical of a “French touch” or, perhaps more specifically, of a Parisian tendency. A meditation on the passing of time, the exhibition blends temporal, signifying, and musical strata across video installations in which expansive scale is not at odds with complexity. In the rotunda, the computer-generated Time No Longer (2021) occupies nearly a third of the wall, generating spectacular immersive special effects based on the image of a turntable playing Olivier Messiaen’s apocalyptic Quartet for the End of Time (1941), the meaning of which intersects with our current concerns. The piece has been rearranged for clarinet and saxophone as an ode to Ronald McNair, an African American astronaut and saxophonist who planned to make musical recordings in space. This installation echoes Take Over (2017), a work that combines two giant screens on which are projected the image of two piano keyboards playing The Internationale and The Marseillaise concomitantly. One composition gradually overlays the other, with a political significance that also evokes the slow process of making works and their historical stratification; indeed, the lyrics of the Internationale were written to accompany the music of the French national anthem before they acquired their own musical identity.

The Palais de Tokyo and Lafayette Anticipations are presenting another spectacular two-part exhibition, “Humpty \ Dumpty” by Cyprien Gaillard, which combines videos and three-dimensional works. Built around the notions of entropy, ruin, and disappearance that run through this artist’s work, the show pays tribute to Robert Smithson by exhibiting a series of his works on paper, and also includes other artists, such as Daniel Turner, whose work has been influenced by these notions. The first part of the exhibition includes a series of very elaborate Polaroids taken on the sites of major construction work in Paris, as well as parts of gargoyles from Reims Cathedral that were slated for demolition and recovered by the artist, who here interrogates the permanent process of destruction and reconstruction that is the city. A spectacular video, Formation (2021), extends across a vast ten-meter panorama that enfolds the viewer, causing a slight sense of dizziness. The second part, shown at Lafayette Anticipations, features a group of new works whose materiality concretizes the entropic character of the city. The exhibition is dominated by Jacques Monestier’s spectacular automaton Le défenseur du Temps (1979), usually installed in the nearby Quartier de l’Horloge and partially abandoned over time. Gaillard had the work restored, thus rescuing it from its gradual destruction. More than four meters high, Le défenseur du Temps moves by a mechanism that is made visible here. It stands next to a painting by de Chirico, Orestes and Pylades (1928), which seems to anticipate it, and next to Le Palais de la découverte vitrifié (2021), a vast square-shaped carbonized monolith made of transformed asbestos, removed from the public monument when it was being made safe.

Despite its title, “Parade,” Guillaume Leblon’s exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo, curated by François Piron, is not very demonstrative. It offers a fundamental reflection on the artist’s practice, allowing for a wide-ranging re-reading and a renewed vision of his work. Eschewing the spectacular, Minia Biabiany’s exhibition “Diafé” (Fire) unfolds in a dreamlike landscape of telluric power, born of earth and fire, in a set of staggering and unusually powerful formal inventions. The exhibition “Schéhérézade la nuit” (Scheherazade at Night) takes a more demonstrative form and shows committed cinematographic and photographic works by Miguel Gomes, Ho Tzu Nyen, Pedro Neves Marques, Lieko Shiga, and Ana Vaz; and a second installation by Minia Biabiany.

In a way, the Centre Pompidou also went in for the spectacular, most notably by reactivating Esben Weile Kjær’s performance Burn! (2019) for the opening of Paris + par Art Basel; and with the video device that presents Iván Argote’s work for the Marcel Duchamp Prize, with its three giant screens. The work’s spectacular quality is tempered by its engaged, political content — subtly echoed by a solo exhibition at Perrotin — and by the quietly radical art of Mimosa Echard, who plays a minimalist and ambivalent game with the viewer by presenting a work that simulates the artist’s studio, isolated by glass like a vivarium or diorama, over which water cascades in a complex stratification of meaning.

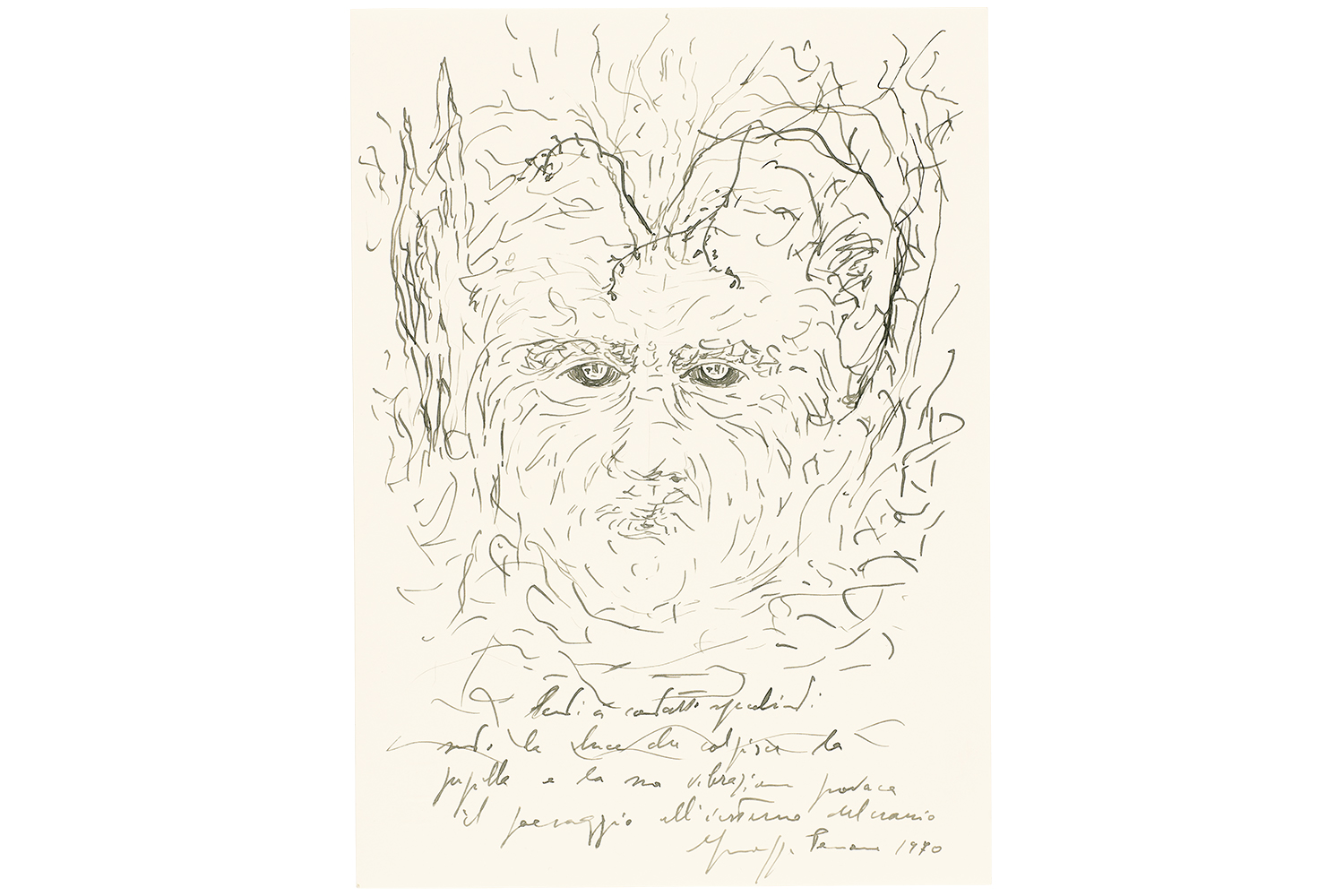

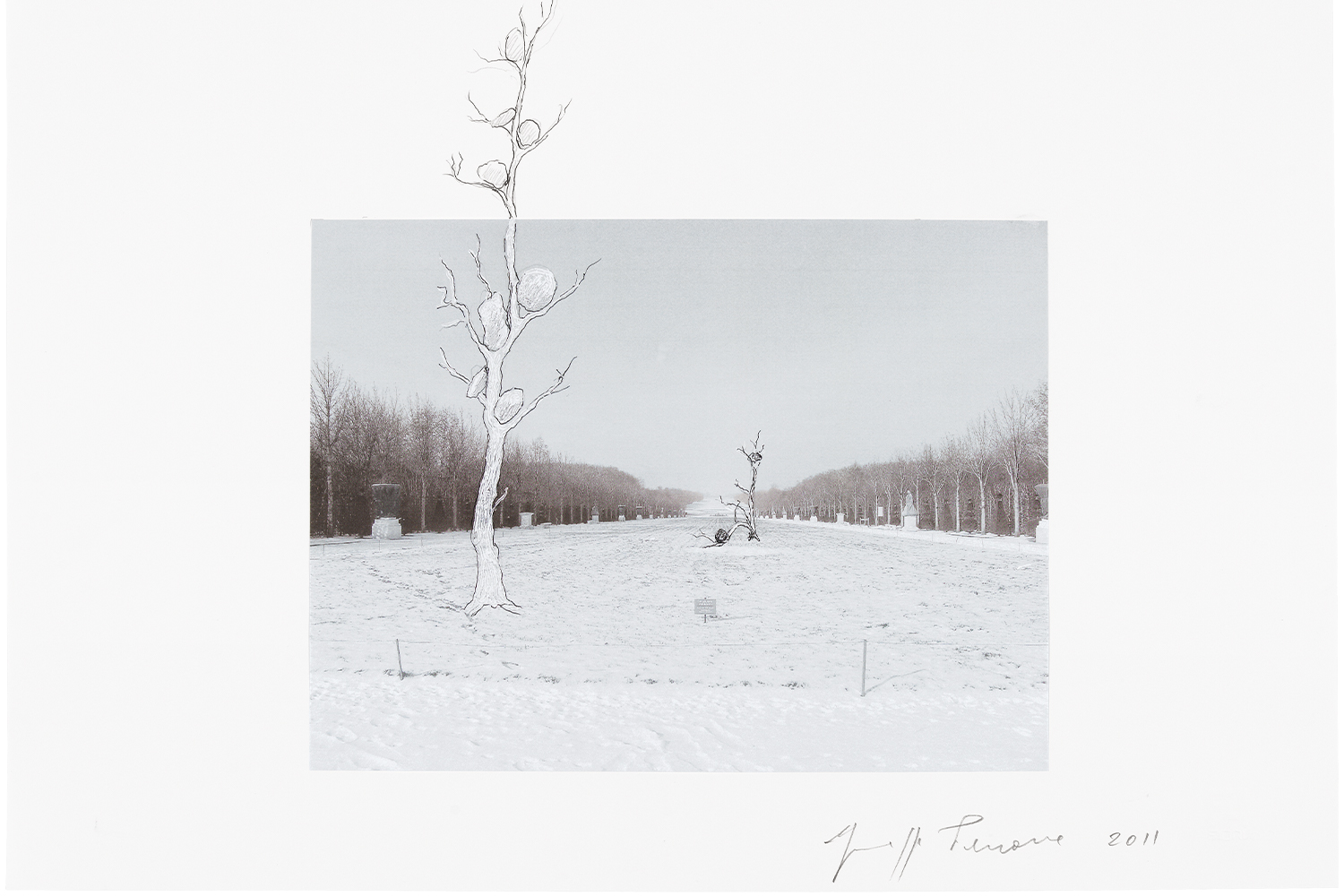

Spectacular and gigantic are terms that hardly apply to Gérard Garouste’s extravagant circular work La dive Bacbuc (1998), part of the dazzling and encyclopedic solo exhibition curated by Sophie Duplaix, which renews the reading of this often wrongly catalogued or misunderstood artist. But with a few exceptions, the spectacular is manifested at the Centre Pompidou essentially in the abundance of its programming, which offers several exhibitions gargantuan in their teeming completeness. The Garouste, of course, but also, as an echo, the sumptuous exhibition devoted to Giuseppe Penone which, modestly announced as an exhibition of graphic works organized around a donation from the artist, takes us into a universe that has not been shown much before, revealing whole sections of a rich graphic output typified by Racchiudere i millenni negli anni (2010), a twenty-six-by-thirty-six-centimeter watercolor and graphite on paper that suffices to symbolize this richness. Many of these works have never been exhibited, and several three-dimensional works echo them splendidly, such as Pelle di Fogli (Skin of Leaves) from 2000, which is shown next to the series “L’impronta dell’ombra sul volto” (The Imprint of the Shadow on the Face, 1999), one of its probable prefigurations.

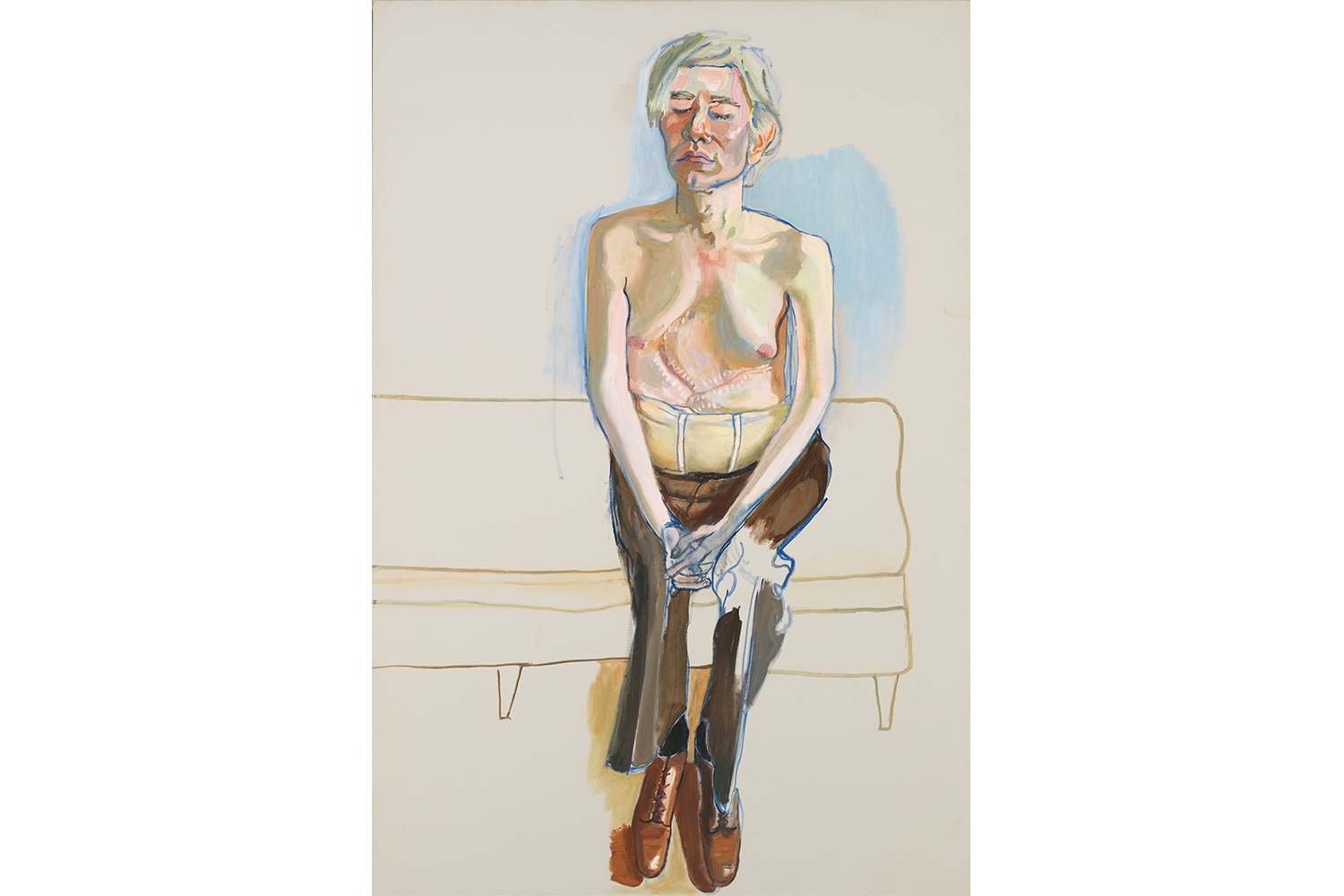

Also at the Centre Pompidou, the exhibition “Evidence,” by Soundwalk Collective & Patti Smith, offers a musical journey along a path haunted by stone and the figures of Antonin Artaud and Arthur Rimbaud. Equally gargantuan is the exhibition “Alice Neel: An Engaged Eye,” which takes a radical look at New York from the late 1920s to the early 1980s, and includes the famous 1970 portrait of Warhol, depicting the Pop icon two years after his attempted assassination — an unshakable image.

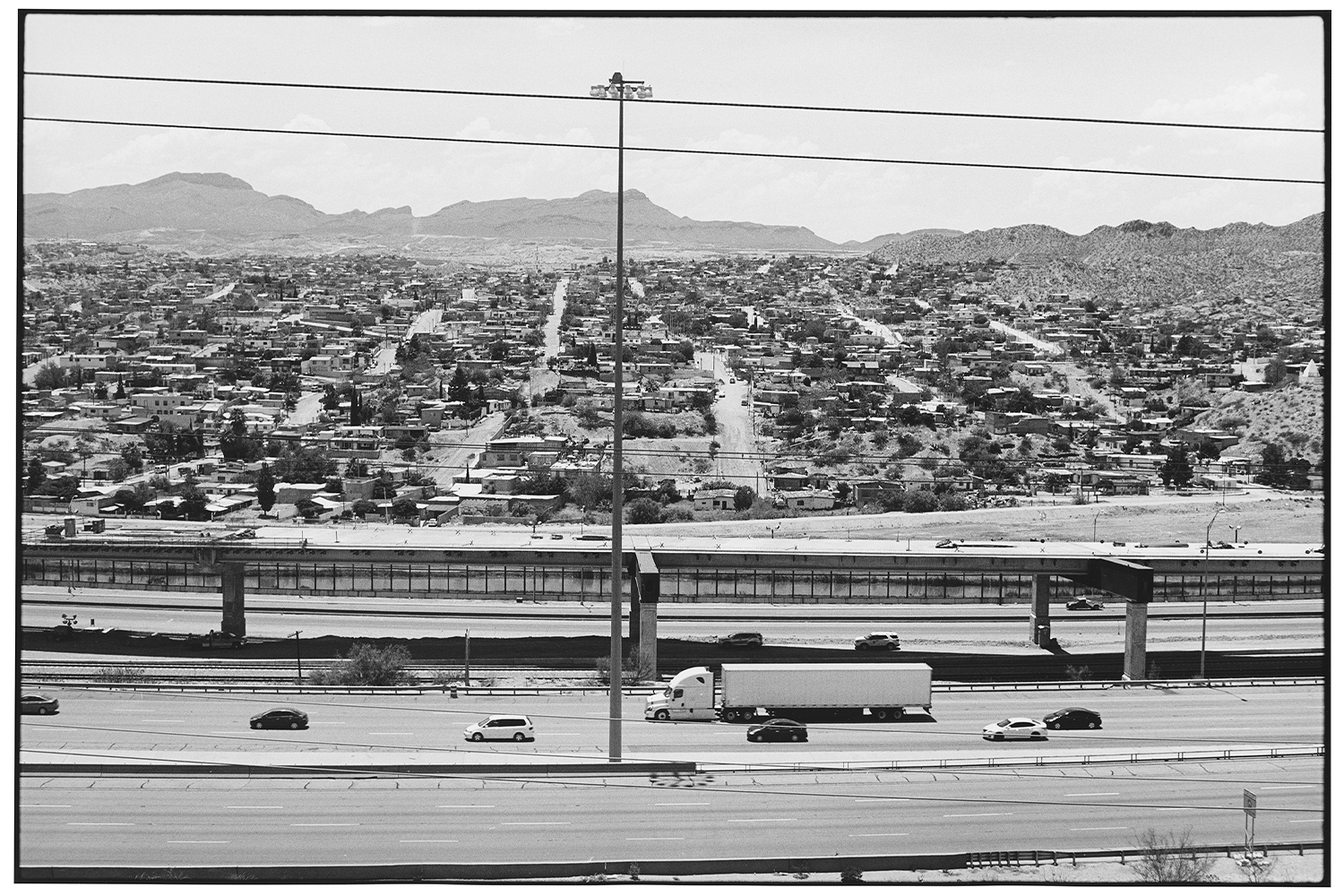

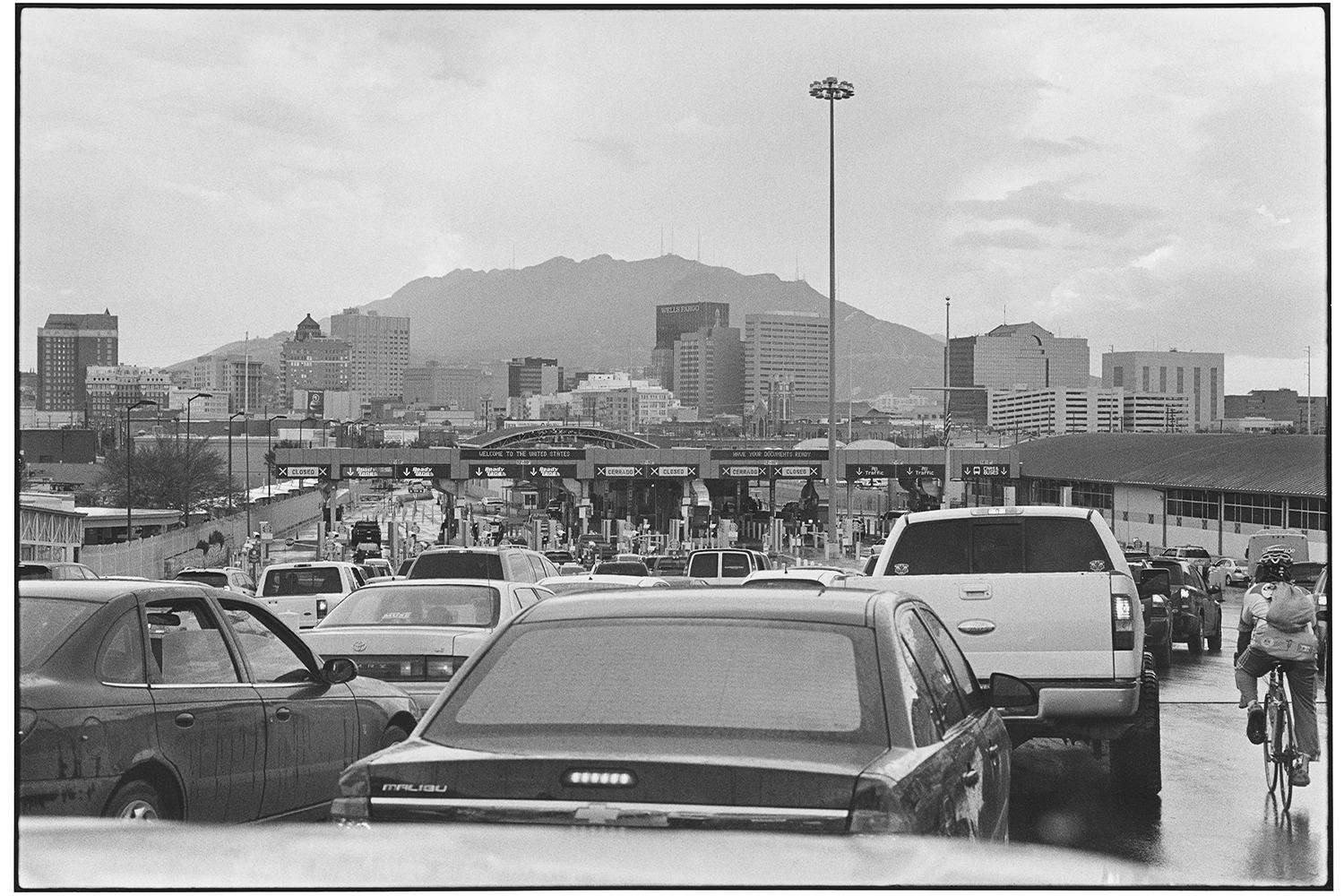

The Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, which is next to the Palais de Tokyo, subtly handles the spectacular and the anti-spectacular in the exhibition “Al río / To the River” by Zoe Leonard. It takes up the elements from her MUDAM exhibition, which showed a group of several hundred photographic works from a series based on the infrastructures of the Rio Grande/Río Bravo River, which acts as the border between the United States and Mexico. The display allows us to grasp the complexity of this work, which invents a visual language that goes well beyond documentary photography and formulates a renewed lexicon through its use of space and thematic iterations.

One of the few exhibitions that resolutely defies the prevailing trend toward gigantism is “Horizones” — a contraction of the words “horizons” and “zones” — which accompanies the 23rd Pernod Ricard Foundation Prize. Curated by Clément Dirié, the exhibition features the work of Benoit Pieron, an emerging French artist whose unspectacular yet fascinating work revolves around transgressive questions about the body, plants, hospitals, and illness; Eva Nielsen, who studies the architecture of peri-urban areas in pictorial works using the silk-screen process; and Elsa Werth, winner of the prize, who puts forward “anti-spectacular productions as tactics of resistance” based on everyday objects and actions. Although it includes monumental works, the exhibition “De Toi à Moi, carte blanche à Jennifer Flay” at the Fondation Fiminco is equally anti-spectacular. It too features a work by Elsa Werth, this time in a very large format and affixed to the glass wall of this former factory, and takes over the whole of the exhibition space along with a powerful installation by Mégane Brauer, which abuts several pieces by Bianca Bondi, Randa Maroufi, and a set of videos, most of which — a delight after all those gigantic screens — are shown on perfect modest monitors.

Also anti-spectacular, the Radicants exhibition “Présentations” shows works by six emerging artists chosen by six curators — including Nicolas Bourriaud, who is at the origin of the structure, as well as Jennifer Flay and Simon Njami. At the opposite end of the scale, the Petit Palais hosts Ugo Rondinone’s grandiose exhibition that includes a new video, burn to shine (2022), projected on six screens inside a monumental cylindrical form made of burnt wood. Similarly, in the Chapelle des Petits-Augustins at the Beaux-Arts de Paris, Omer Fast’s Karla installation continues his research about the complexity of the boundary between truth and representation with a device that includes a hologram projection; and Andreas Angelidakis’s installation Center for the Critical Appreciation of Antiquity (2022) also establishes an immersive dialogue with its host architecture at the Espace Niemeyer.

As a final counter-echo to gigantism and the spectacular, it seems to me that Judith Hopf’s two-part exhibition “Energies” at Bétonsalon & Le Plateau/FRAC Île-de-France is actually a direct critique of it. The show is articulated around sculptural works that represent anonymous characters that photograph the visitor with smartphones, thus inciting us to reverse our gaze and consider the major question of energy from both ecological and political perspectives. What is energy? How is it produced? But also, perhaps, what is artistic energy? Next to an installation by Sylvie Fanchon, the figure with the smartphone turns toward us from the windows, inviting us to photograph him in turn, and prompting even further critical distance.

We might wonder what lies behind this recourse to gigantism and the spectacular. Of course, it’s all about attracting international VIPs and the biggest buyers, being on the same wavelength as other artistic capitals, yet managing a very Parisian marriage between content and form — or so I said to myself as I strode through Paris. But perhaps it is also a strange and paradoxical echo of the current crisis. The grandiose or the spectacular allows certain works to be enhanced and sometimes leads to a re-reading when it serves a purpose and does not sink into vacuity. As noted by the research of the academic George Taylor in 1926, and updated recently by several international studies, we know that clothing lengths tend to shorten when times are optimistic and to lengthen when they are pessimistic. We can therefore presume, paradoxically, that since screens are so large and hems are so long, that everything is going badly in terms of content but well in terms of form, and that we will have to cope with that.