Like coexisting layers of history, the works of Austin Martin White superimpose figure, ground, and ghostly apparitions. In the lofty space of Capitain Petzel in Berlin, a 1964-built pavilion that is a prime example of GDR modernism, White’s paintings and drawings glow in the sunlight pouring in from the south-facing windows. The show is titled “Last Dance,” and it tackles the intricate relationships between post-industrial spaces and club culture, colonialism, and the material that the 1984-born painter uses to fashion his images: rubber.

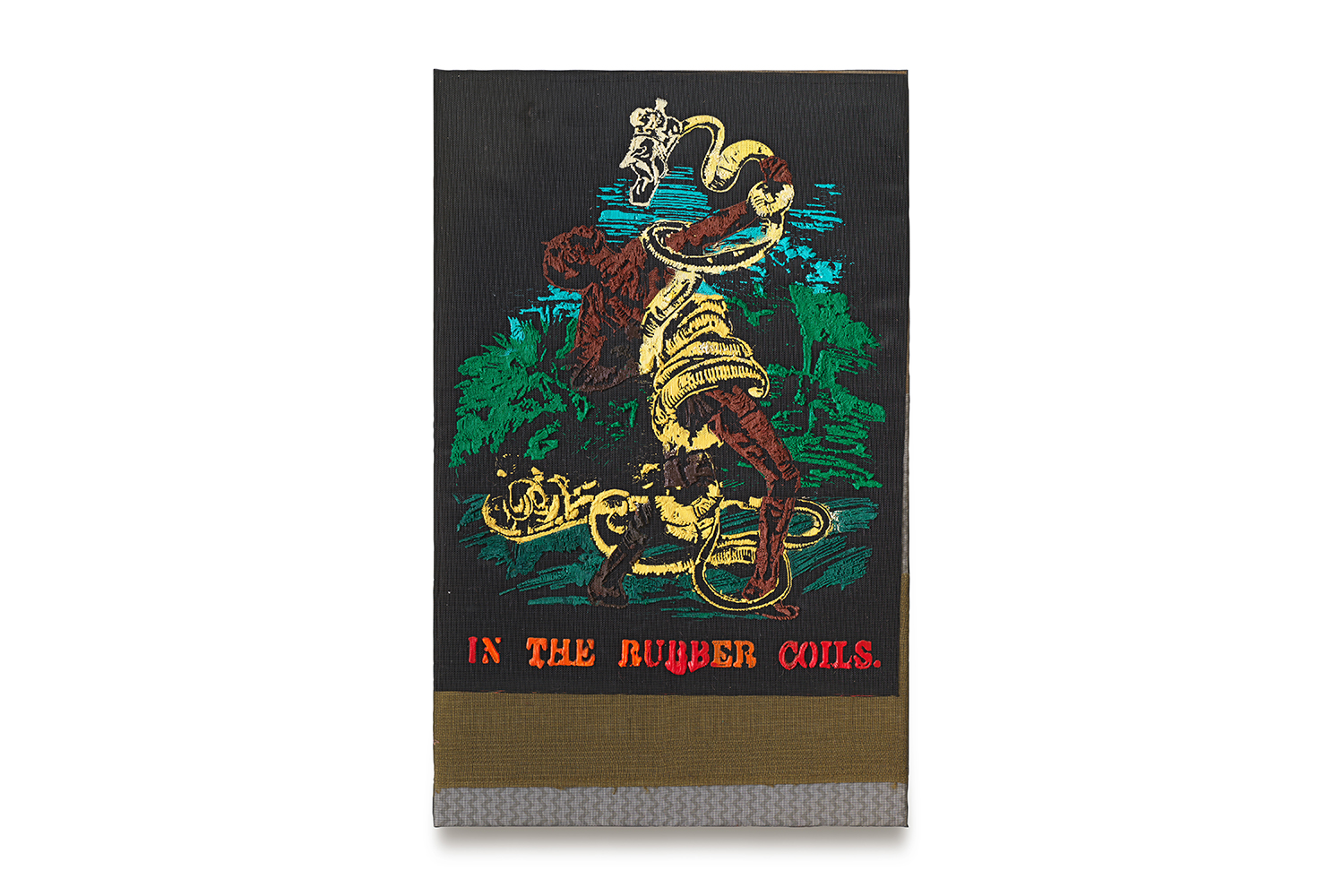

The show in Berlin initially appears exuberant and colorful. The first image you see is based on a cartoon from 1906, which depicts a Black man — a Congolese rubber collector — who is attacked by a snake. The snake represents the Belgian colonial extraction of rubber. White renders the scene in bright colors on a dark ground. This is also one of the smaller formats in the show; most of the other paintings approach two meters or more in width.

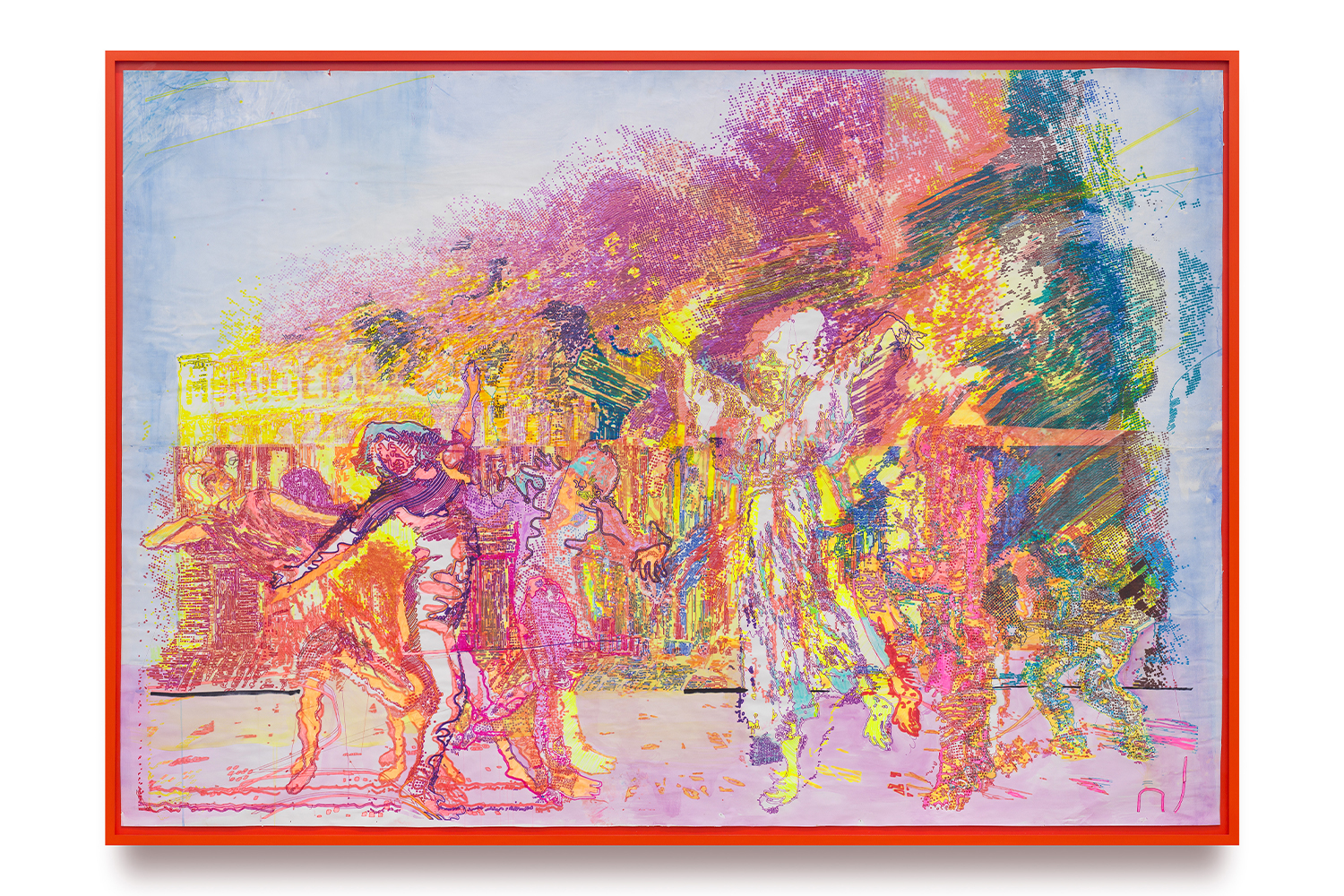

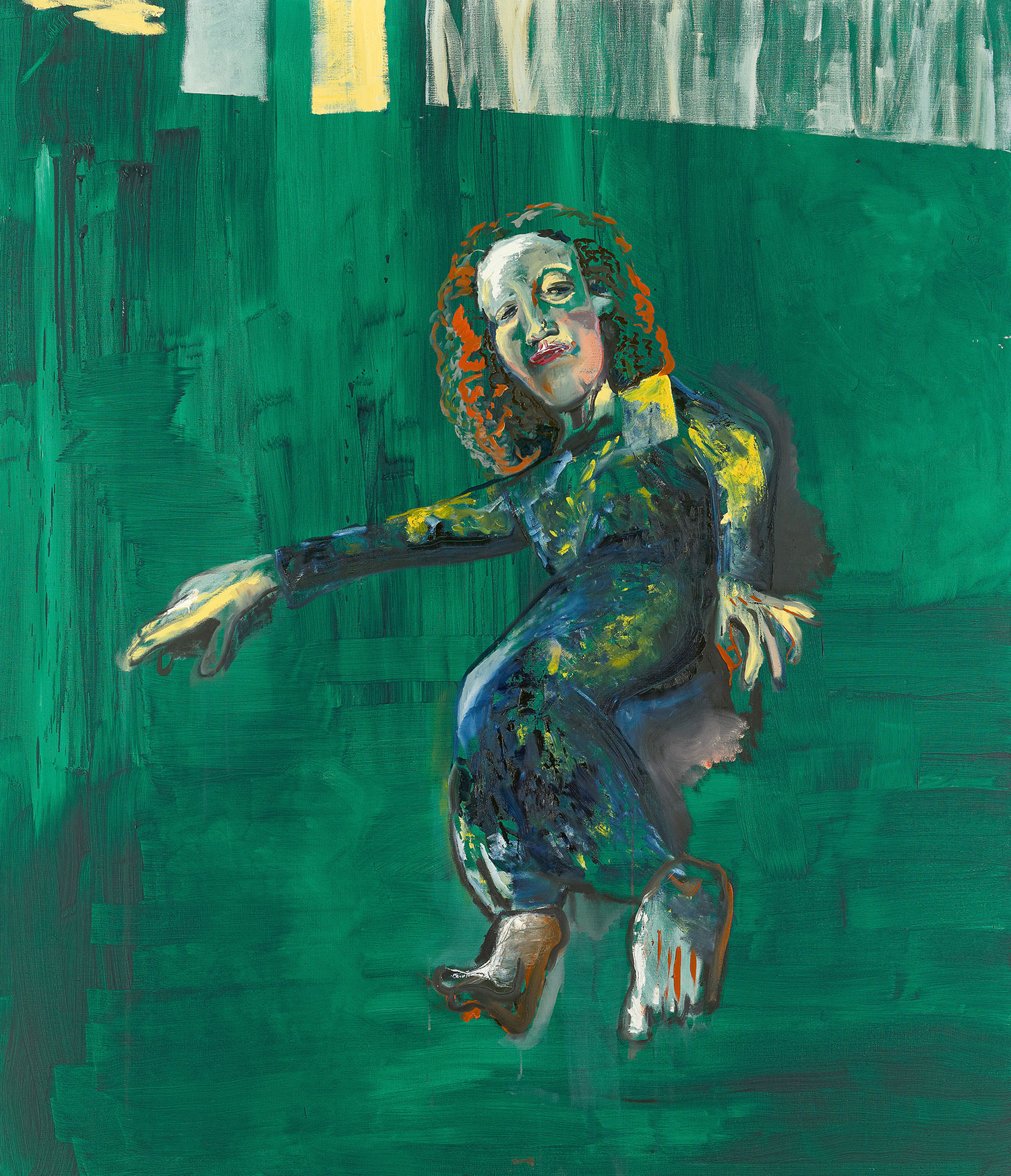

Some of the paintings seem to deal with scenes of joy, with partying in the ruins of, well, maybe history, as the title of the show suggests. Take fireatthechurchofclubs (Bye Bye Berghain) (2022), one of the large-scale paintings, which depicts a group of about six people in ambivalent poses. How do we read these ghostly apparitions? Are they dancing or are they in agony? White picked bright pinks, yellow, and orange for his rendition. The palette extends to the frame, which is almost a day-glo orange. In the background, a large, looming building is on fire, immediately identifiable as the techno club Berghain by the large banner that reads “Morgen ist die Frage,” which was part of an art show held at the club during the pandemic. Maybe White seeks to point out the elective affinities of Berlin and Detroit, where he grew up at the tail end of the city’s decline. Both places share a rich club culture and have incorporated techno into their cultural heritage, as places where the efficiency of machines is turned into a catharsis, a depletion of energy. Notably, the basement of the gallery also housed a club in the 1990s.

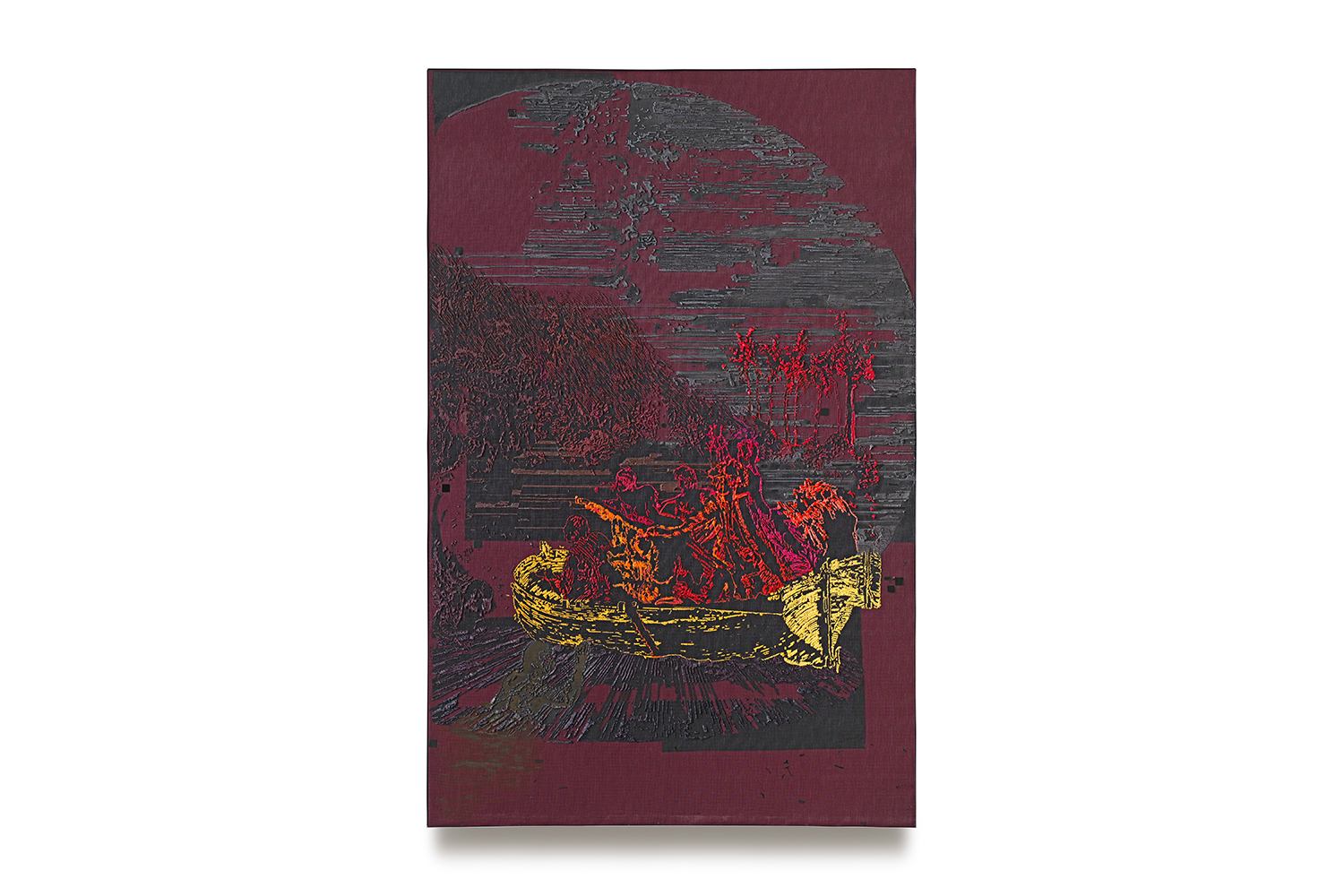

White’s paintings are layered in form too. Vinyl glistens behind the mesh, changing as the viewer moves. In some of the pictures he included a reflective material, which, with the shifting light, creates different silvery effects. The artist eventually started working with the kind of mesh used for window screens to create a textile-like grid. He modified the process and began employing a machine for vinyl cutting to create masks behind the screen. Some works include small rectangular patches where the mesh tore, and they act like a kind of painterly punctum, a detail that ruptures the surface and catches the attention. White then replaced the blade of the machine with a ballpoint pen, allowing the apparatus to transpose vector drawings onto paper.

The latter process resulted in a series of somber, detailed drawings that reference Fordlândia, a prefabricated town in Brazil that Henry Ford dreamed up in the 1920s. The drawings are based on historical depictions of the place, and White arranges the elements in the drawings like a painter would, situating figures in order to aid the narrative. The industrialist Ford wanted to control the rubber supply for his car-manufacturing enterprise — and here the connection between Detroit, (neo-)colonial extraction, and White’s material of choice comes to bear.

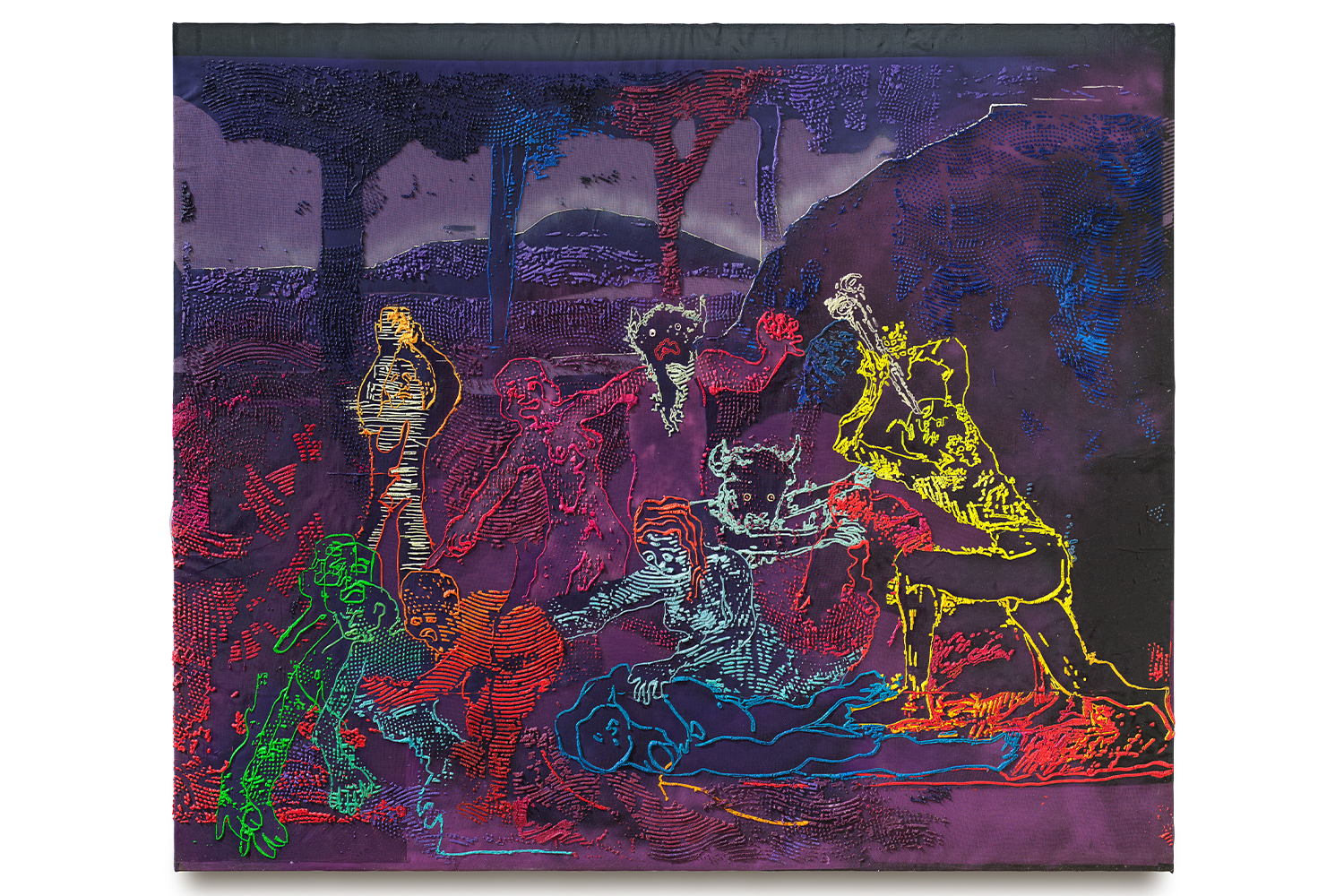

Colonialism and its imagination are a recurring concern of White’s. He researches etchings from the time of Western expansion in North America, slowly building resources for his own work: images of African American costumes for Mardi Gras in New Orleans; depictions of Native American dances, which, however, were kept secret from invaders. Only a constructed memory remains. White’s work allows a glimpse of fugitive joy in the last dance, which always contains an element of resistance.