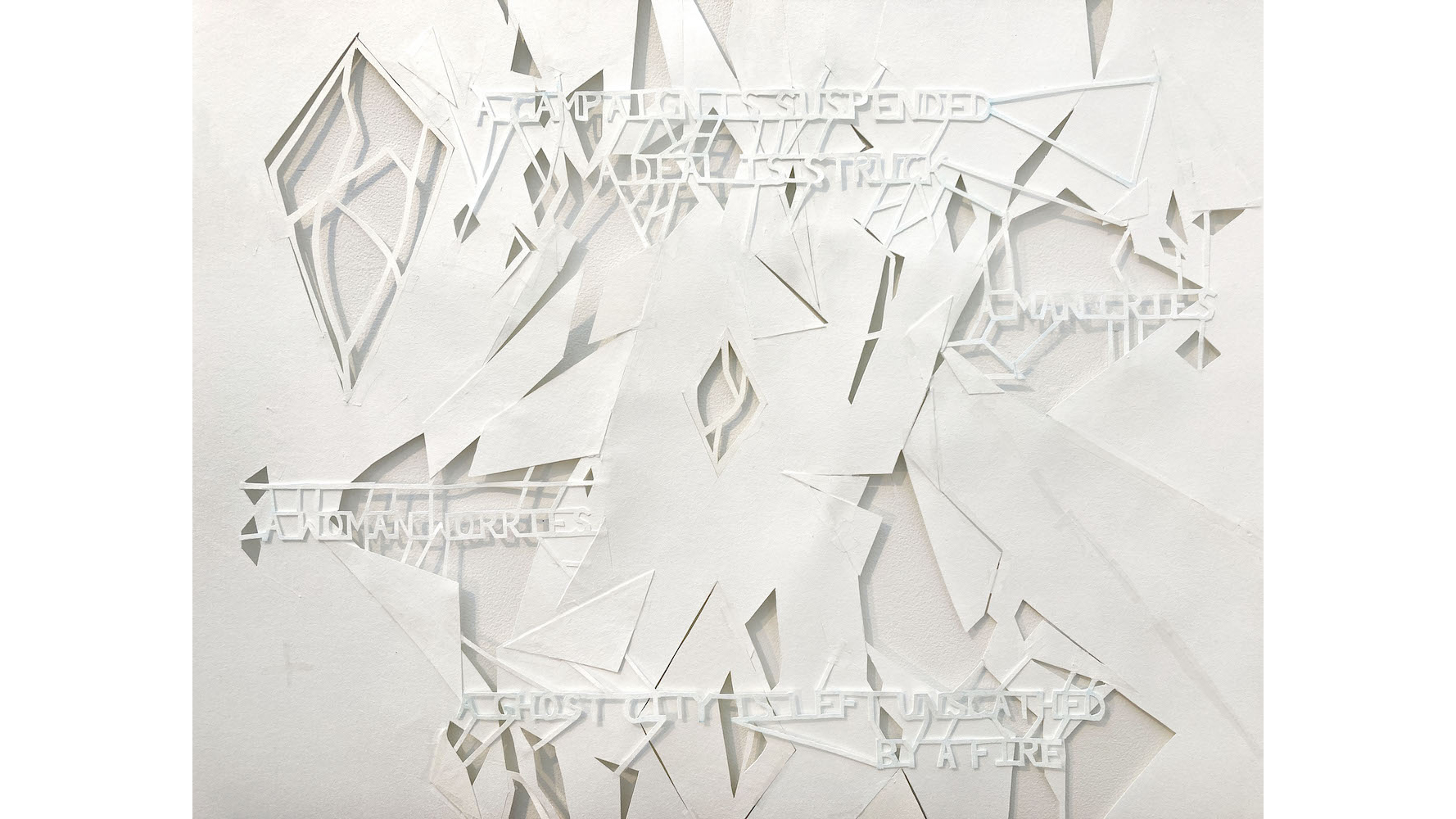

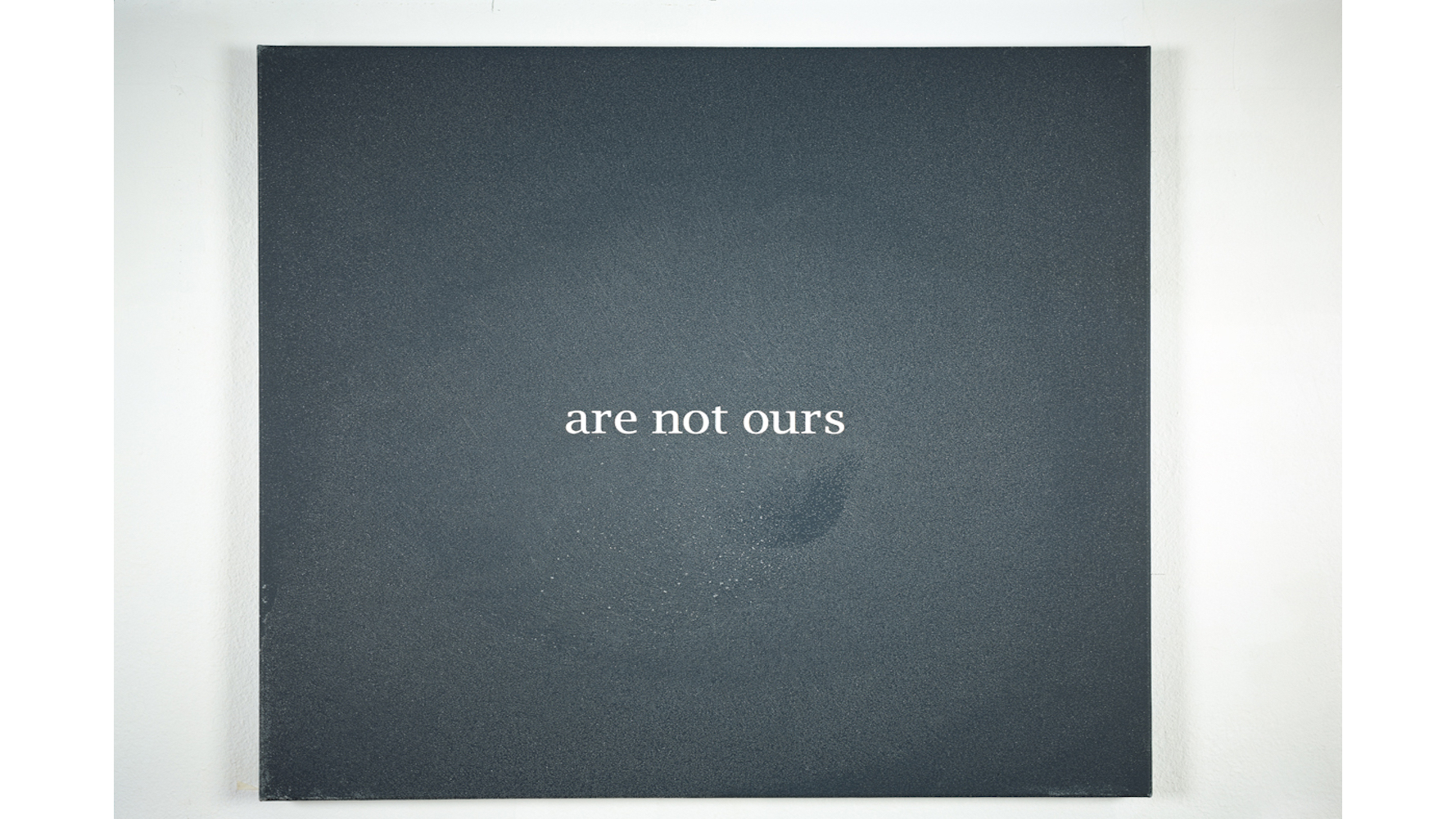

“January 21, a country announces its first case of a virus.” “January 23, a city is sealed off to prevent the spread of a virus.” “August 20, a woman feels hopeful.” These events, along with 362 others, are recorded in Annabel Daou’s film a year like any other (2020), which is showing at Galerie Tanja Wagner for Berlin Gallery Weekend 2021. Daou’s video accompanies twelve works on paper that also memorialize the days and months of a year that was both exactly like and nothing like any other. The works profoundly consider the flattening effects created by a year during which the world underwent a traumatic collective experience, very often from the perspective of individual isolation. When one is alone and atomized, a drone strike on a general, an exploding tanker, a firework display all become subsumed in the infinite flow of information about the “outside,” while personal acts like knotting blades of grass together in a park — and being legally allowed to do so — take on the character of headlines.

Daou’s work seemed to capture the spirit of Gallery Weekend in the city’s new COVID reality. The art critic’s routine experience of Berlin’s vernal gallery fiesta this year included the grim preliminary of queuing at one’s local COVID test center and awaiting a negative test result before proceeding to cycle between and among the more than forty newly opened shows. Melancholia and lamentation stalked many of the strongest exhibitions. Galerie Konrad Fischer, for example, opened a mournful but beguiling exhibition by the Turner Prize-winning artist Susan Philipsz. The show’s title, “Slow Fresh Fount,” is taken from a Ben Jonson poem of exquisite sorrow: “Slow, slow fresh fount, keep time with my salt tears; / Yet slower, yet, O faintly gentle springs! / List to the heavy part the music bears.” The poem imagines a lament by Echo at the death of Narcissus. Philipsz’s work disarticulates the four vocal parts from a madrigal based on the poem, wordlessly singing each discrete part. The parts are played from speakers attached to the lids of oil drums, and the ensuing echo moves through the cavernous space of the gallery. The song, in Philipsz’s rendering, is composed as much by what is lost as by what is heard.

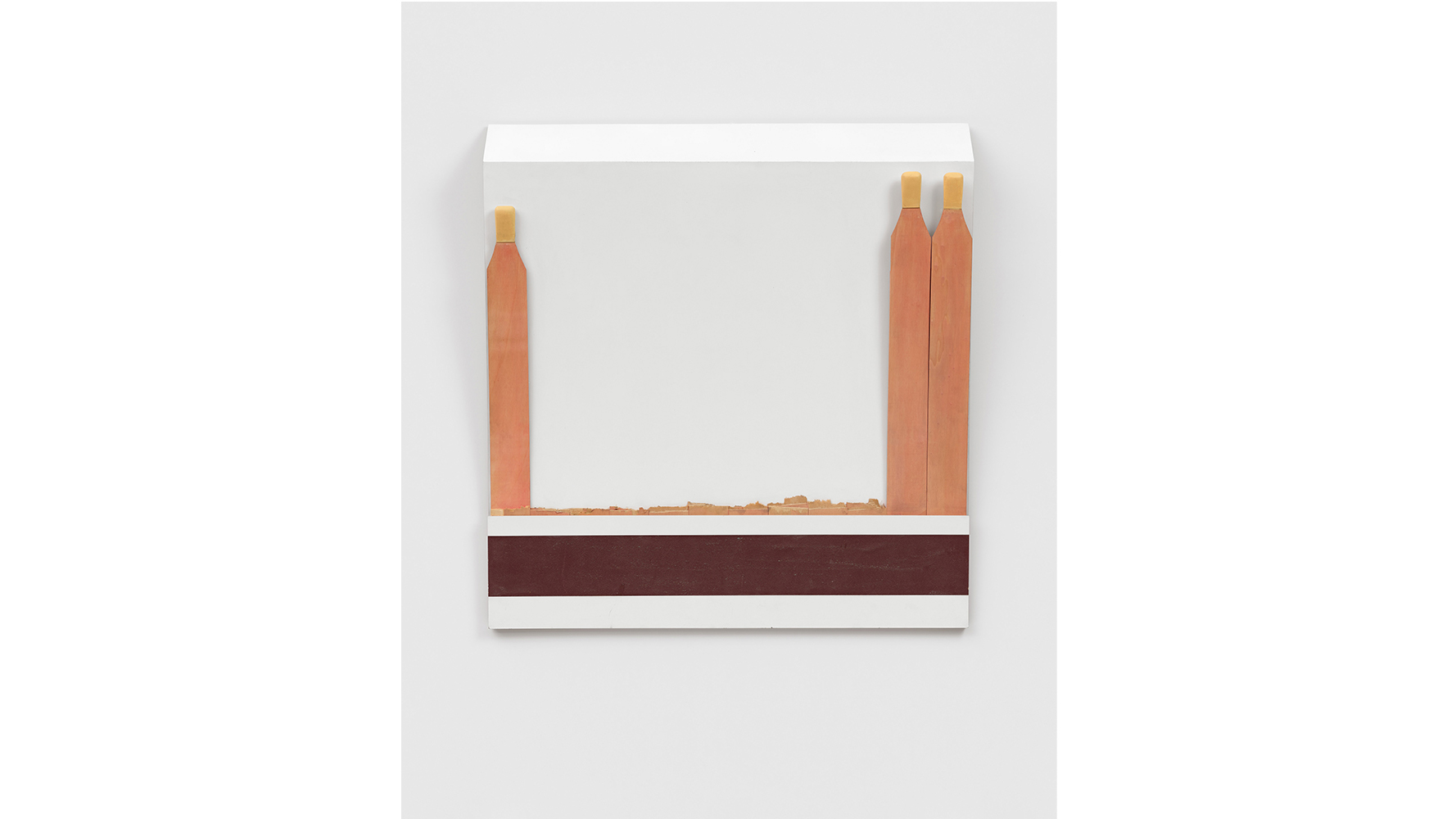

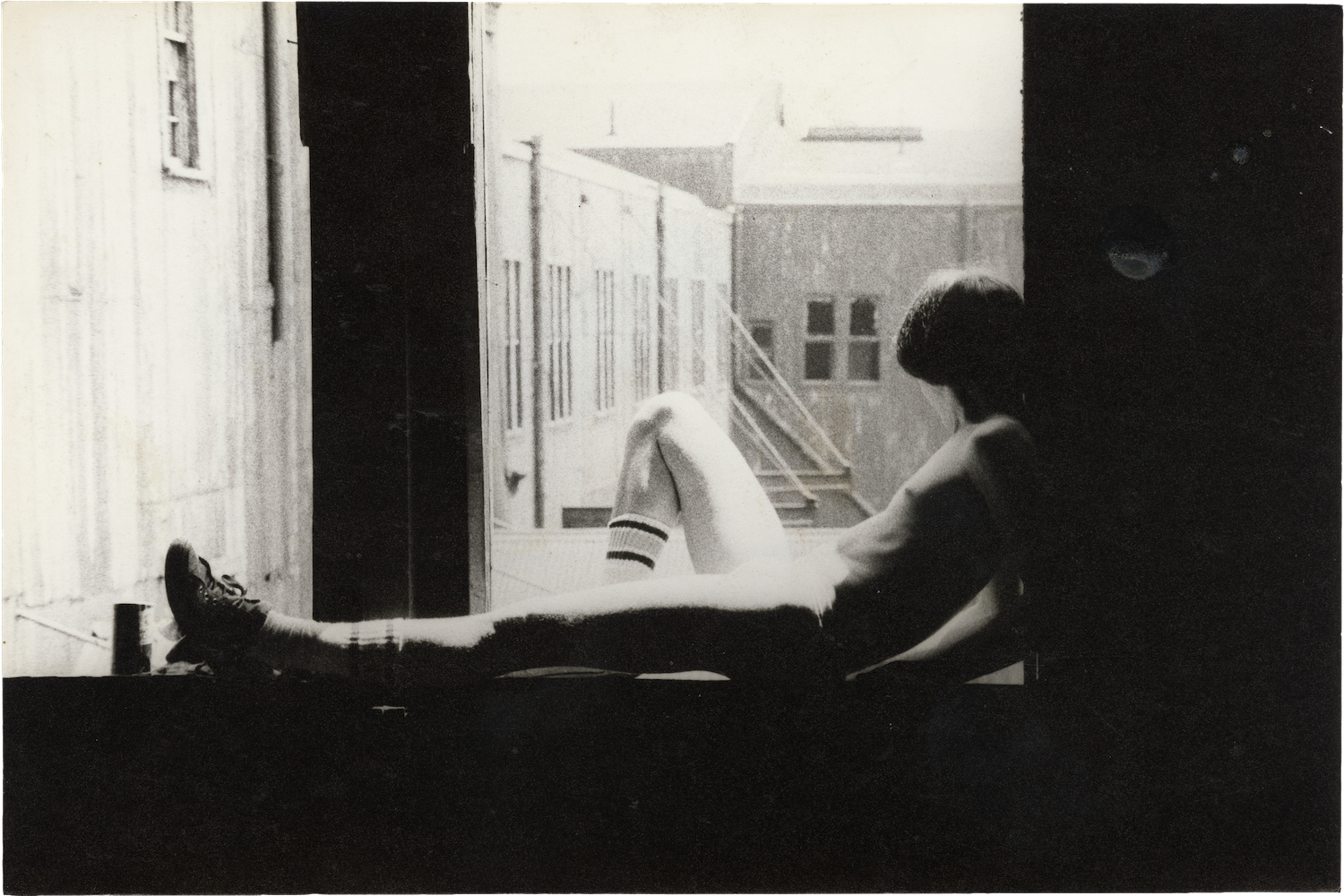

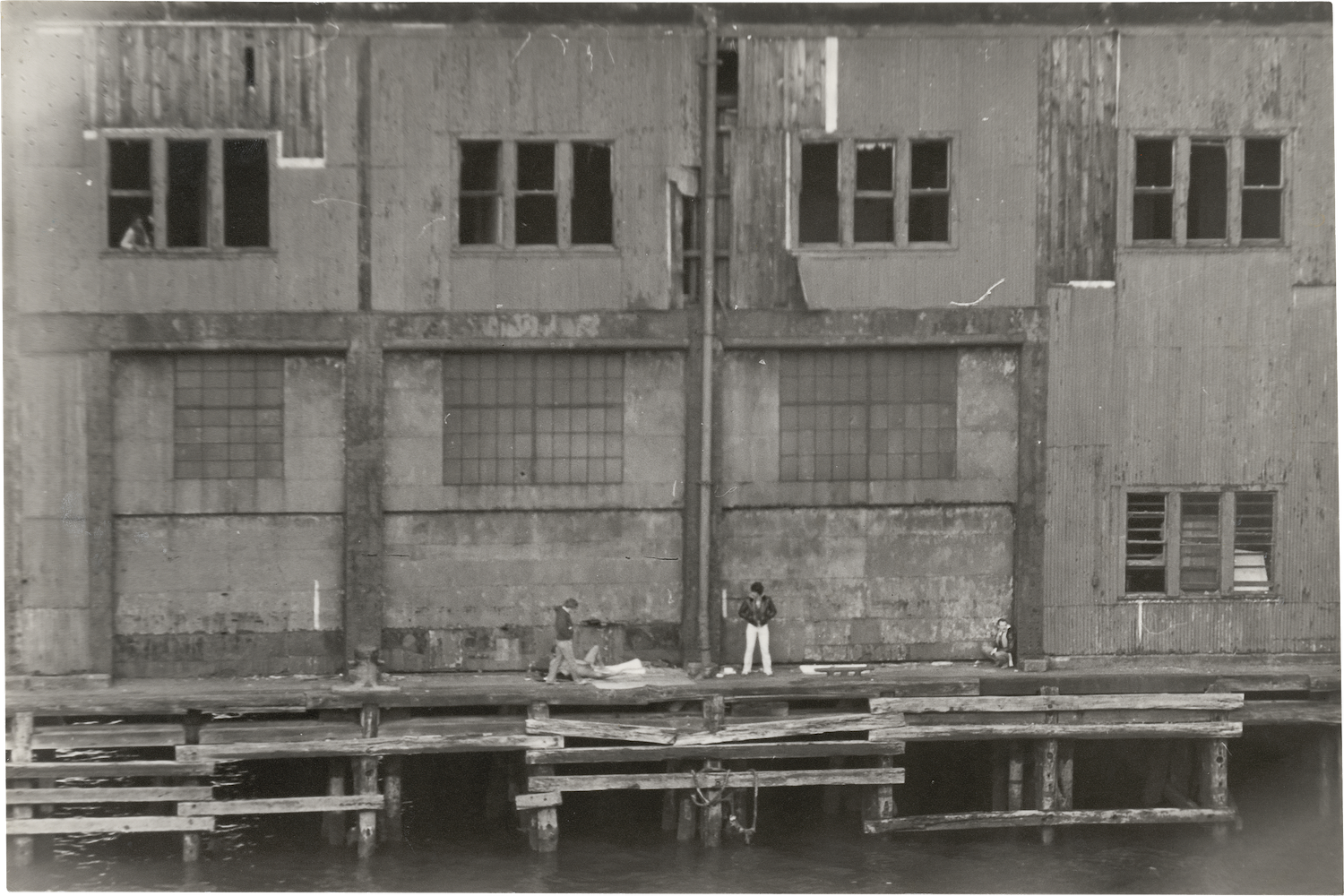

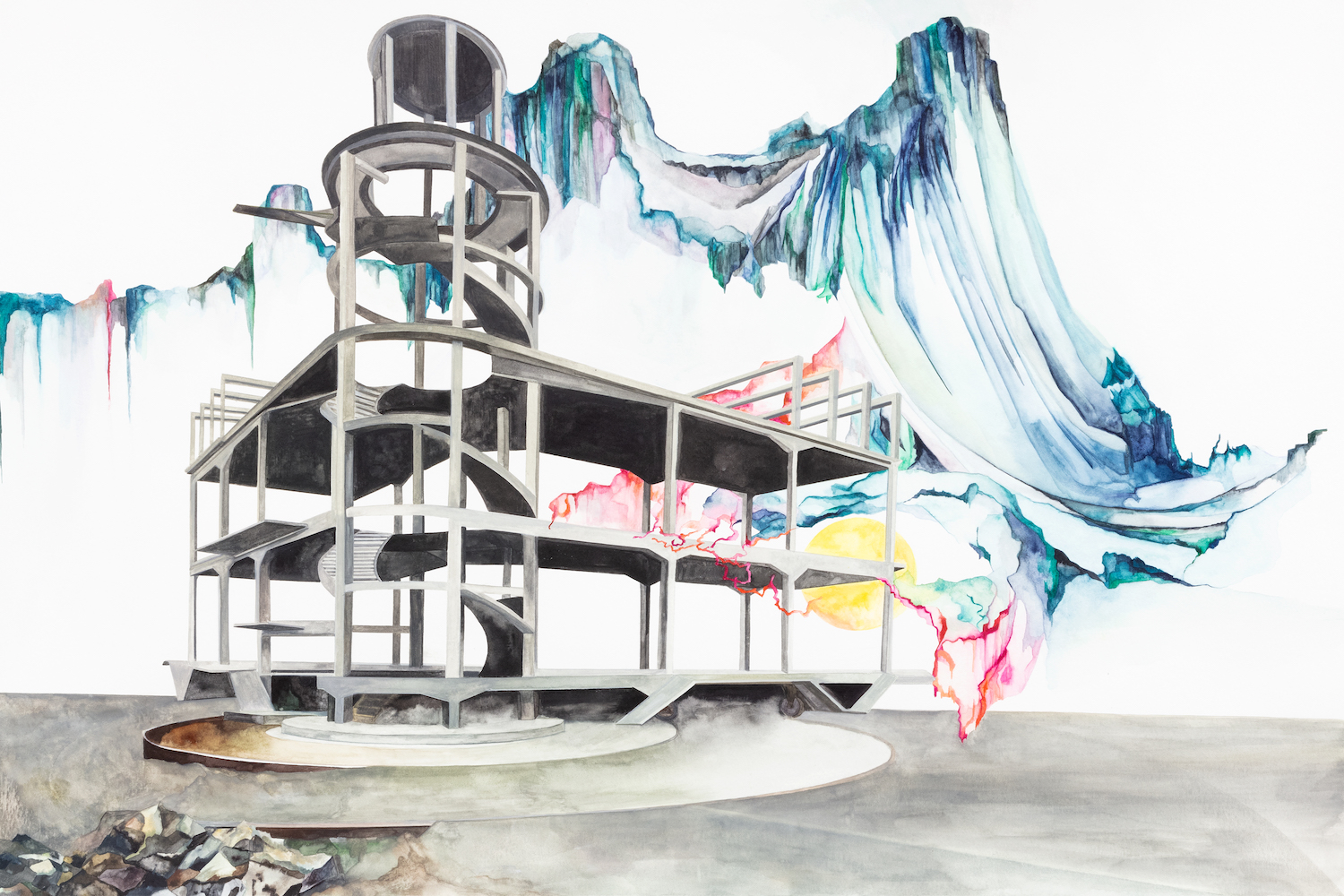

Loss and lost time also permeated a pair of exhibitions in Charlottenburg, one at Lars Friedrich Gallery, the other at Galerie Buchholz. In the case of the Lars Friedrich show, a two-hander featuring works by the anarchic Swiss conceptualist Christian Philipp Müller and his younger colleague the Portuguese artist Ricardo Valentim, the exhibition considers the joys and anxieties of influence, and reflects upon — and materializes — the passage of time and the passage of friends and ways of living. Titled “Kunst und Freundschaft” (Art and Friendship), the exhibition could be subtitled “Time Flies When You’re Having Fun.” At Buchholz a generous show of photographs by Alvin Baltrop, spanning a period from the 1960s through to the mid 1980s, concentrates on gay life in and around NYC’s abandoned piers, including the notorious Pier 52. Given the times they depict, Baltrop’s photos cannot escape a certain elegiac quality; celebration can turn to memorialization without warning. While it is true that the power dynamics of some of Baltrop’s images read somewhat uncomfortably to today’s viewer, his studies of piers themselves and the seascapes beyond speak urgently to the overwhelming fragility of the present.

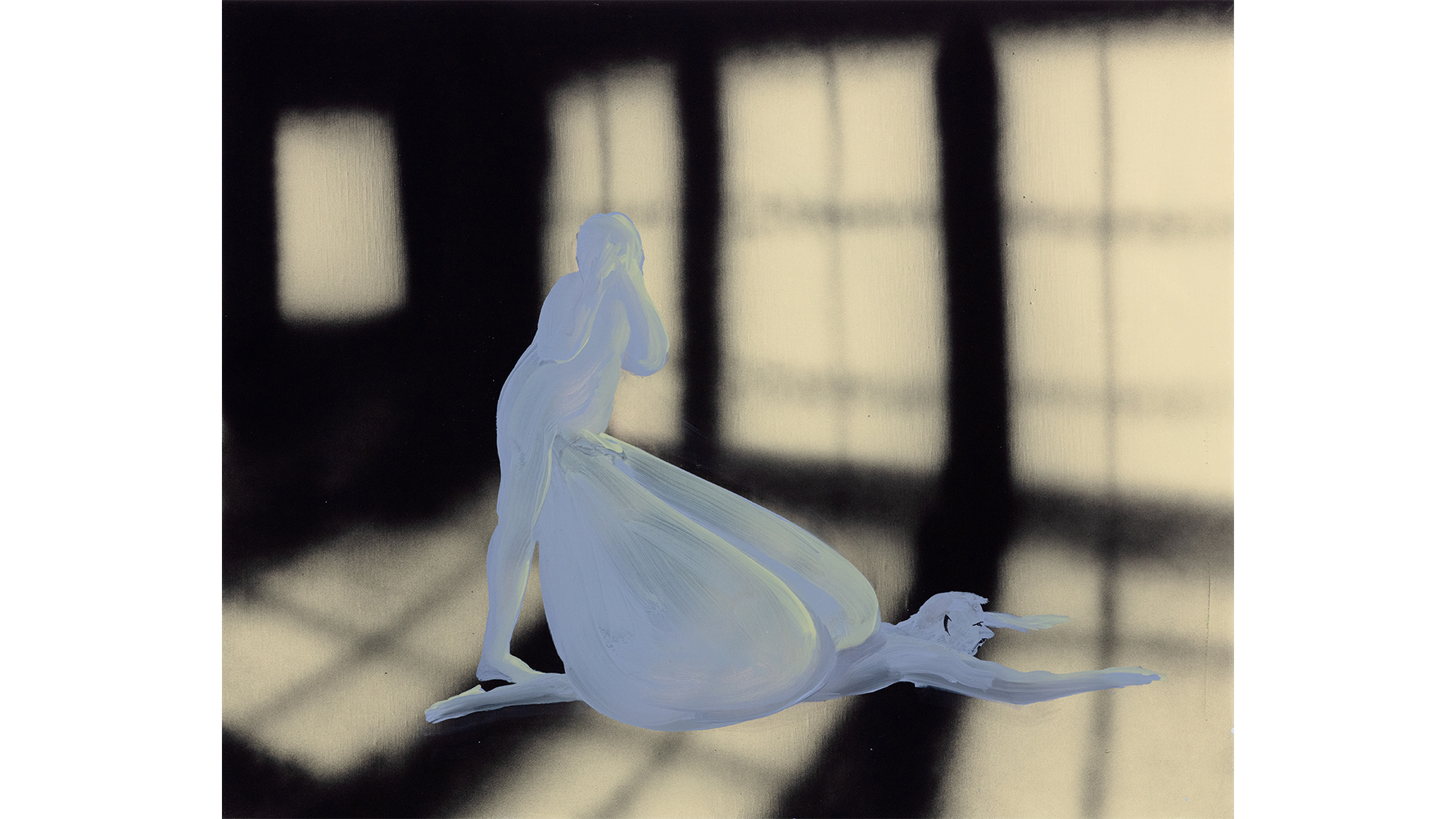

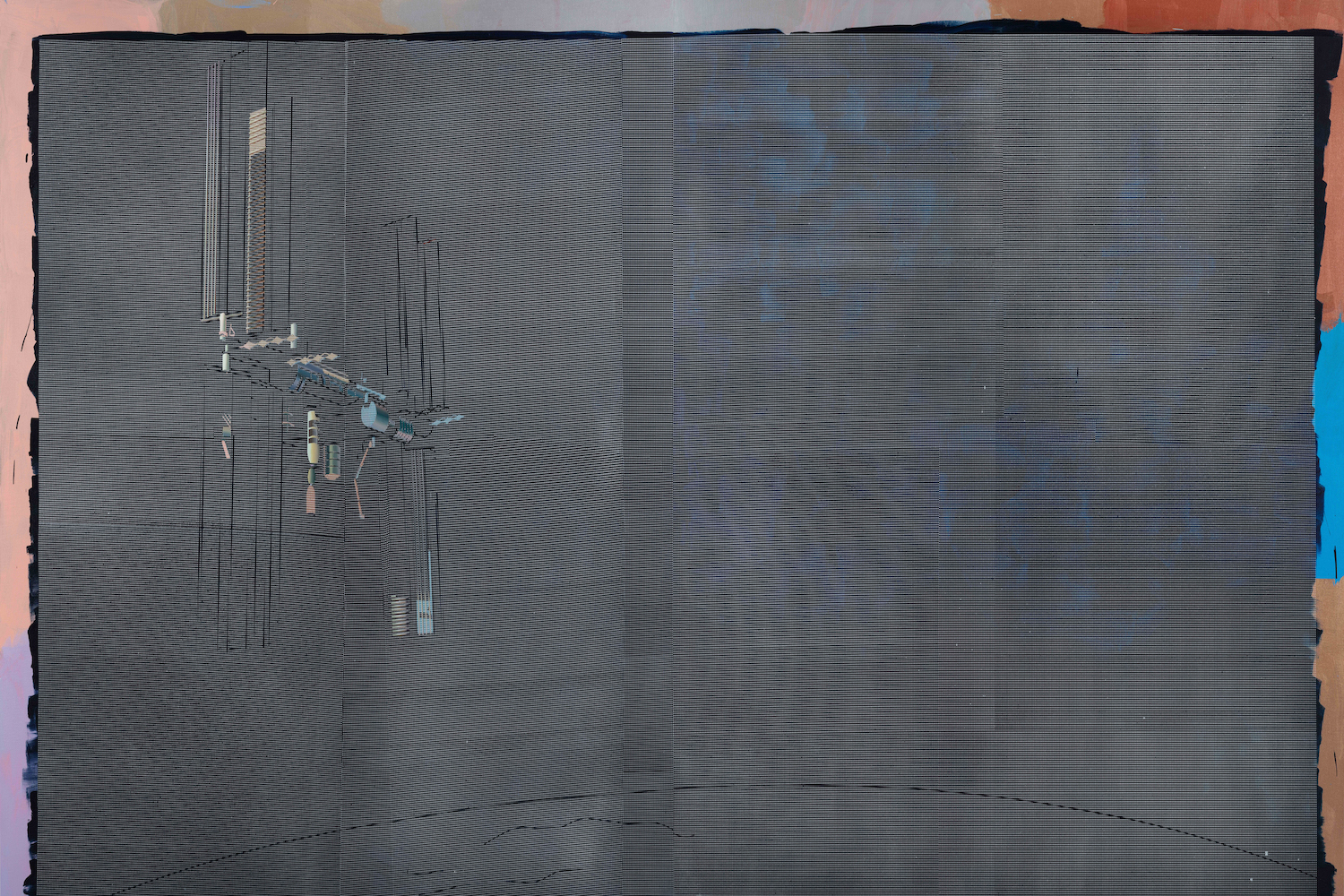

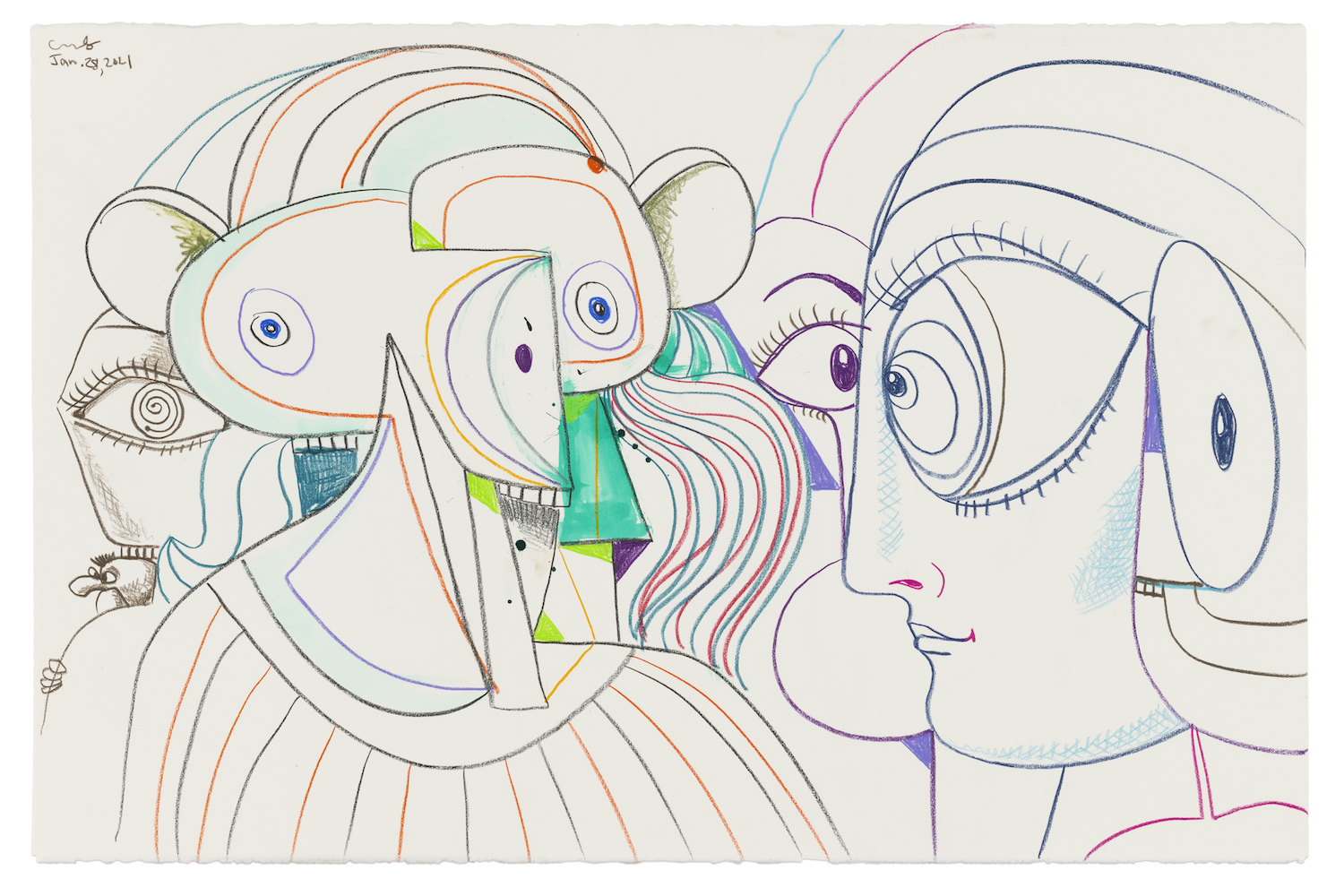

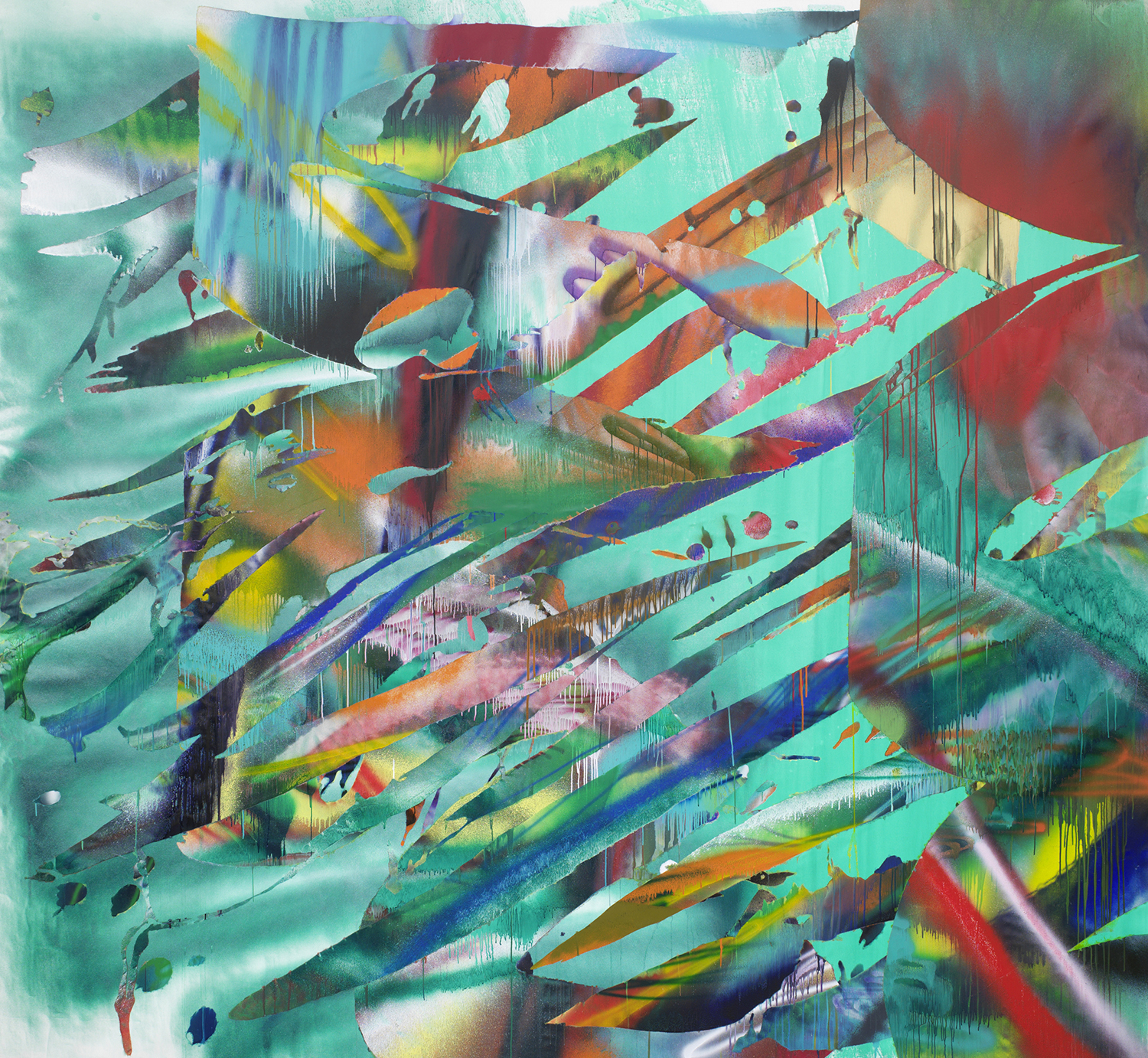

While a certain ambient somberness was inescapable, it would be overly reductive to say that all the shows from Gallery Weekend were downbeat. Vibrant paintings by Maki Na Kamura were on show at Contemporary Fine Arts, and Diango Hernández presented the trippy “Instopia” at Barbara Thumm’s space. “Hell, Yes!” at the Horse and Pony project space in Neukölln was a breath of the freshest, most madcap air, particularly with its series of lockdown drawings by Ryan McNamara (sadly, however, the show couldn’t open to the public because of legal restrictions on nonprofit spaces). Galerie Max Hetzler hosted a triumphant exhibition of new paintings by the great Albert Oehlen, and Galerie Barbara Weiss opened a fascinating, cerebral series of works by the young painter Jannis Marwitz. But even shows that offered a surface nod to the pleasures of empty calories, like Kayode Ojo’s glittery “Call it What You Want,” the inaugural exhibition at Sweetwater’s new space, featuring sequins, disco balls, and a parade of chandeliers, had heavier undercurrents. Indeed, the droop in Ojo’s chain of chandeliers seemed to gesture toward the exhaustion of performative good cheer that clutters many an Instagram feed this year.

The sense of dancing as fast as one can (in a city without any open clubs) also seemed present in two of the major public art exhibitions of Gallery Weekend. Katharina Sieverding’s billboard project Deutschland wird deutscher (1993) has reappeared throughout Berlin under the auspices of the KW Institute, and “Die Balkone 2” across Prenzlauer Berg (curated by Övül Ö. Durmusoglu and Joanna Warsza) attempted to offer contemporary art to people living in Berlin unable to come to galleries. The works themselves were often powerful. Sieverding’s challenging historical project, undergoing the palimpsestic defacements common to all Berlin billboards, whether they be emissaries of art or commerce (or both), continues to hold up a mirror to the contemporary German experience. The Prenzlauer Berg Balconies offered a plethora of artistic possibilities, but these works’ very existence sometimes generated uncomfortable dynamics, sometimes among residents of the city living nearby — for better and for worse — but more generally as manifestations of the tension between indomitability and coping. A Gallery Weekend like no other, but perhaps more like ones to come than can be easily contemplated.