Dance Office is a column dedicated to contemporary dance and performance art.

Collaboration is cocultivation. It’s the merging of two dreams into one. It’s life and death in the aesthetic zone. One entity makes an incursion into the possibilities/plans of the other — the choreographic into the visual, let’s say, and/or vice versa. — Trisha Brown, 1999

On October 20, 1983, the Trisha Brown Company debuted the twenty-five-minute dance Set and Reset as part of the inaugural Next Wave festival at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. The looping electronic score — a vibrating, percussive soundtrack titled “Long Time No See” — was composed by Laurie Anderson, who played the violin live that evening, along with Richard Landry on saxophone. The visual presentation, which included the stage set and the costumes, was designed by Robert Rauschenberg, with lighting by Beverly Emmons. As part of a 1982 grant application that Rauschenberg had submitted to the National Endowment for the Arts, he anticipated, “Working with Trisha Brown + Laurie Anderson will be one of the most unique theatrical challenges in my career […] No one could be more curious about this than I am.”

Trisha Brown Dance Company, Walking on the Wall, 1971. Still from the performance. 20-30′. Courtesy of Trisha Brown Dance Company.

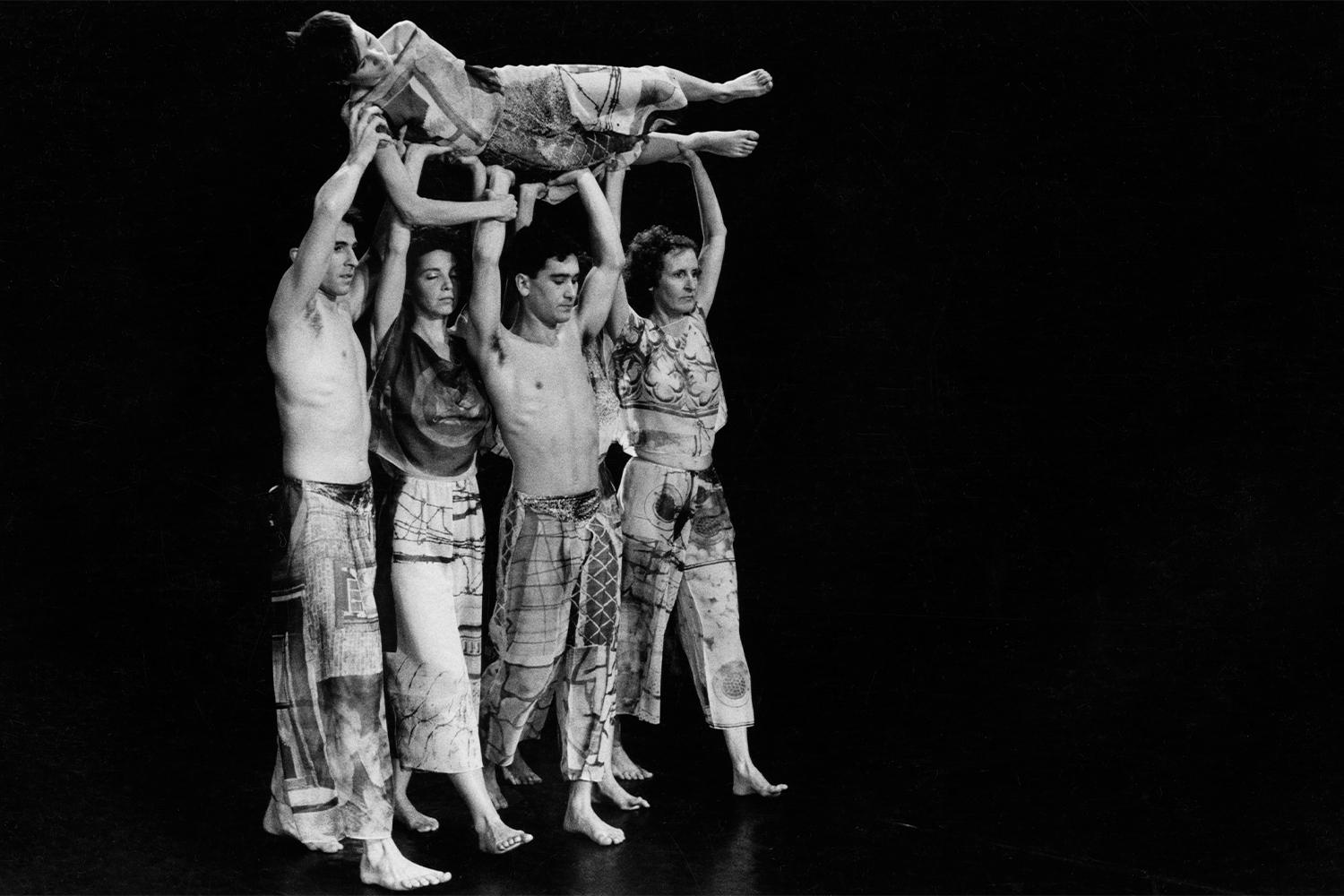

Reflecting on the performance in Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961–2001 (2002), Brown wrote, “I started work on Set and Reset knowing only that Laurie Anderson would compose the music and that I would reconstruct a solo version of Walking on the Wall as part of the new piece.” Walking on the Wall — one of Brown’s legendary ‘equipment pieces’, in which performers suspended on harnesses stood, walked, and ran parallel to the floor — had premiered at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1971. Dianne Madden, a dancer in the Trisha Brown company, noted that Set and Reset began with the phrase “walking on the (backstage) wall,” where “[one dancer was] handheld by four dancers with outstretched arms, her feet to the brick, the crown of her head to the audience. It looks like the radical 1971 equipment piece, but the dancers are now wearing gorgeous costumes.”

Since 1979, with the debut of Glacial Decoy at the Walker Art Center, Brown had transitioned from staging work in alternative performance sites in New York (from downtown lofts and galleries to the street and rooftops) and instead began choreographing large-scale works for the traditional proscenium stage. Brown’s perception of dance as an extension of everyday life endured, and she continuously cited from her radical archive when devising these new dances. Her choreographic process took the form of “memorized improvisation,” in which her company memorized complex improvisational moves, through a laborious rehearsal process, as a way of capturing that initial spontaneity.

Although Rauschenberg and Brown had met in the early 1960s, connected through Merce Cunningham and their involvement in the Judson Dance Theater, Glacial Decoy marked their first artistic collaboration. The group of individuals who had gathered at Judson Memorial Church ranged from choreographers and dancers to visual artists, composers, designers, and filmmakers, and Brown embraced the theatrical space as an opportunity to continue this artistic legacy of expansive cross-disciplinary dialogue. In her catalogue essay “Collaboration: Life and Death in the Aesthetic Zone” for Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective (1999), Brown explained, “[My transition] to the proscenium theatre in 1979 required expertise in the visual aspects of lighting, scenography, and costume. I turned to Bob. He knew the ropes. He had been wreaking havoc on the dress and behavior codes of conventional theater for decades.”

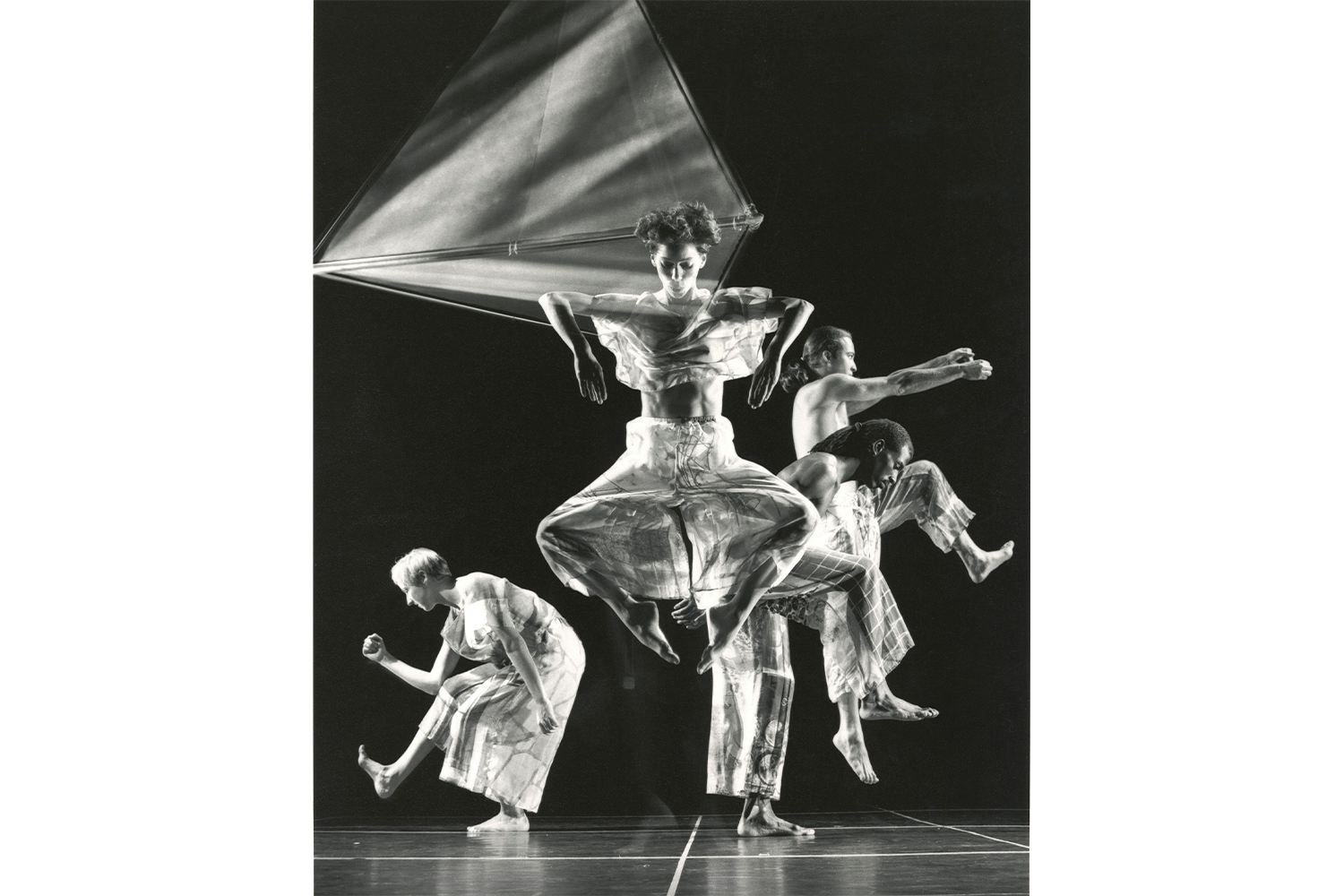

For Set and Reset, Rauschenberg designed the overhead geometric structure Elastic Carrier (Shiner), which was suspended above the stage. The central form was a large rectangular translucent box, made from a sheer white fabric stretched over an aluminum frame, with smaller pyramidal forms on either side comprised from the same material. A rolling sequence of four black-and-white films, edited from archival newsreel stock footage capturing the urban environment, were projected onto the structure, frenetically and endlessly dissolving and refracting through the scrim’s translucent layers. For the dancers, he designed loose-fitting costumes from a diaphanous mesh material, with elasticated waistbands and wide legs, and silk-screened photographs of New York over the garments using a pale-gray-to-black color range. “[To] provoke your looking past the costumes and back to the dance,” he commented. Emmons then proceeded to light the dancers with particularly warm color tones in order to contrast and complement Rauschenberg’s cool hues.

Brown had commented that Rauschenberg’s playful decision to replace the wing curtains found on both sides of the stage — which typically “demarcate the difference between onstage behavior and off” — with a see-through black fabric meant that “our sanctuary is gone, invisibility dashed, down-time on display.” Through the sheer wings, the dancers are always on stage, and there is no central focus. With this traditional framing undermined, “the outside edge of the stage [serves] as a conveyer belt to deliver duets, trios, and solos.” Since the 1960s, Brown had explored walking, running, and falling as forms of energetic choreographed movement, thinking about the body in a state of constant flux and motion. Set and Reset was one of a series of works she had grouped under the term “unstable molecular structures.” Throughout Set and Reset, dancers run and fall, moving and holding their bodies at 45- and 90-degree geometric angles, interacting with one another through direct, physical contact, while also maintaining control, fluidity, and momentum. On composing the score, Anderson commented, “Falling has always interested me on many levels, but I had never tried to make music that fell.”

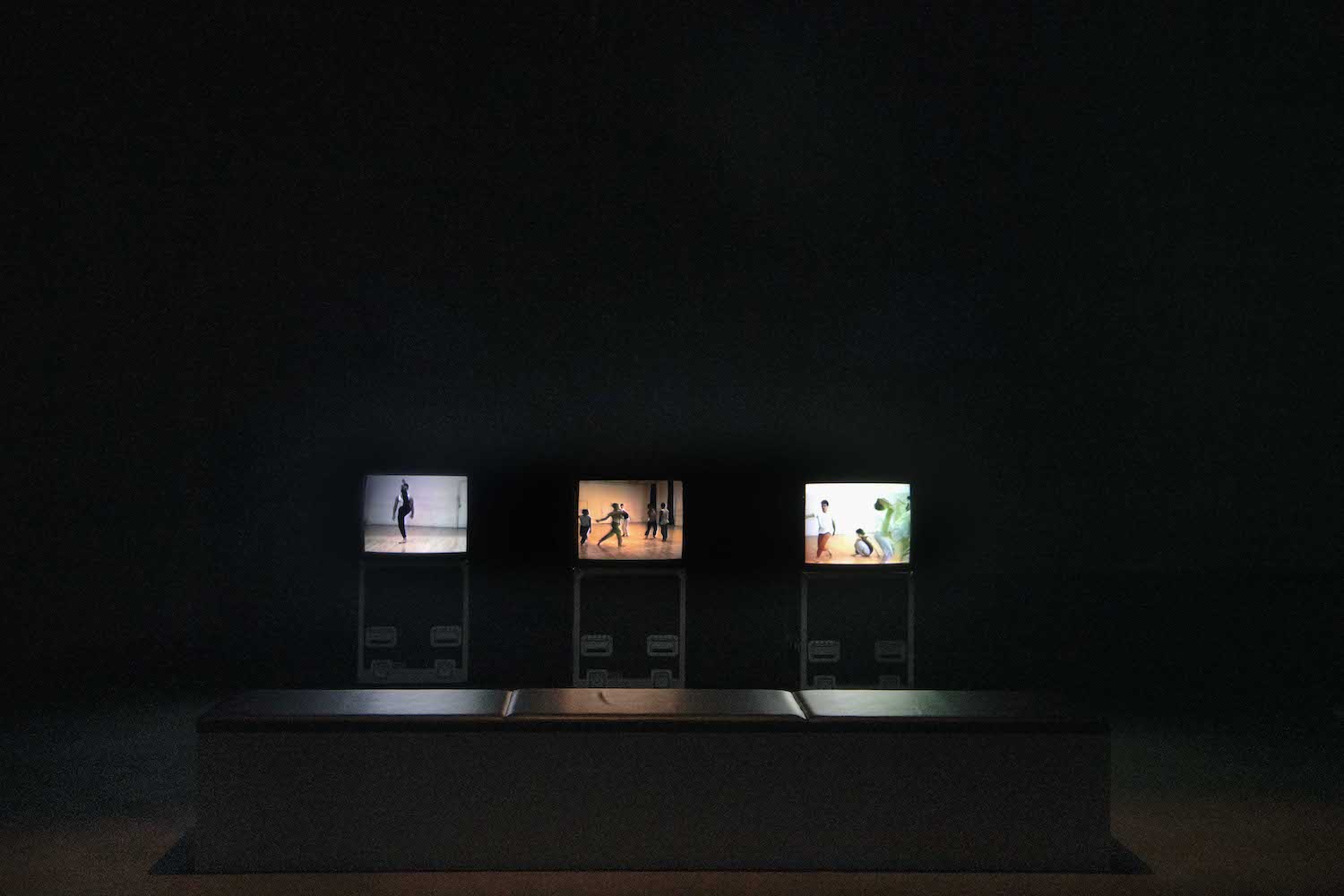

Tate have now acquired Set and Reset (specifically: the stage set, costumes, soundtrack, and lighting) for their permanent collection, with the acquisition initiating opportunities for the museum to explore how an institution can show and historicize works of dance and performance. The current Set and Reset exhibition display in the Tanks at Tate Modern includes Anderson’s music and Rauschenberg’s Elastic Carrier (Shiner). There are also monitors showing video footage taped at the original rehearsals, alongside cinematographer and photographer Babette Mangolte’s film Trisha Brown WATER MOTOR (1978). By way of activating the installation and keeping the dance alive — through what the curators refer to as a form of ‘intergenerational transmission’ — Tate programmed live performances from Candoco Dance Company and Rambert, which took place across two consecutive weekends in mid-March. These events also formed part of the Dance Reflections by Van Cleef & Arpels Festival.

Dancing in Rauschenberg’s original costumes, Rambert learned Set and Reset specifically for the Tate commission, through an intensive four-week rehearsal led by current members and dancers of the Trisha Brown Company. While their process was guided by the principle of repetition, by directly replicating the original, Candoco’s Set and Reset/Reset is motivated by collaboration and expansion, improvising and playing with the existing phrase to build a new movement structure. Candoco — an integrated company of disabled and non-disabled dancers — have been performing Set and Reset/Reset, this reconstructed version of Set and Reset, as part of their repertoire since 2011. Their original choreography was devised by Abigail Yager, a former member of the Trisha Brown Company, who used Brown’s original instructions as a guideline when working on this new version.

While making Set and Reset in 1983, Brown had given the dancers the following five instructions:

1. Keep it simple (The clarity issue).

2. Play with visibility and invisibility (The privacy issue).

3. If you don’t know what to do, get in line (Helping out with downtime).

4. Stay on the outside edge of the stage (The spatial issue).

5. Act on instinct (The wild card).

Yager has described Set and Reset/Reset as, “[examining] the shifting nature of choreography in relation to underlying structures that anchor a dance to itself. The process of re-construction (as opposed to replication) is a negotiation between freedom and limit — an exploration of possibility.” In a panel conversation that coincided with the performances, Joel Brown, a dancer in Candoco, elaborated on the improvisational process as providing a space in which the company are able to play with and explore each other’s different physicalities and personalities. Set and Reset/Reset becomes an act of movement translation. It is perhaps akin to the concept of ‘remixology’, as a remix acknowledges its lack of sameness, while maintaining a sense of continuity with the original.

For their performance at Tate, Candoco danced underneath Elastic Carrier (Shiner), but their usual touring set was originally designed by David Lock, a former Candoco dancer, who created the backdrop from a series of monochromatic layered materials. The design was based on Rauschenberg’s ideas, but unlike Elastic Carrier (Shiner), it would be compact, portable, and easy to travel with. Their costumes, which similarly echo Rauschenberg’s designs, were designed by Candoco’s co-founder Celeste Dandeker-Arnold.

In addition to these performances, Tate have programmed a series of informal performances (ongoing until August), titled Set and Reset/Unset, in which Rambert dancers will return to the Tanks to perform sections of Brown’s choreography. With the absence of a stage, and visitors watching the performance from throw cushions sprawled across the floor, the performances have inadvertently carried Brown’s work away from the proscenium stage, and back to her roots in the unconventional, alternative site of the art gallery.