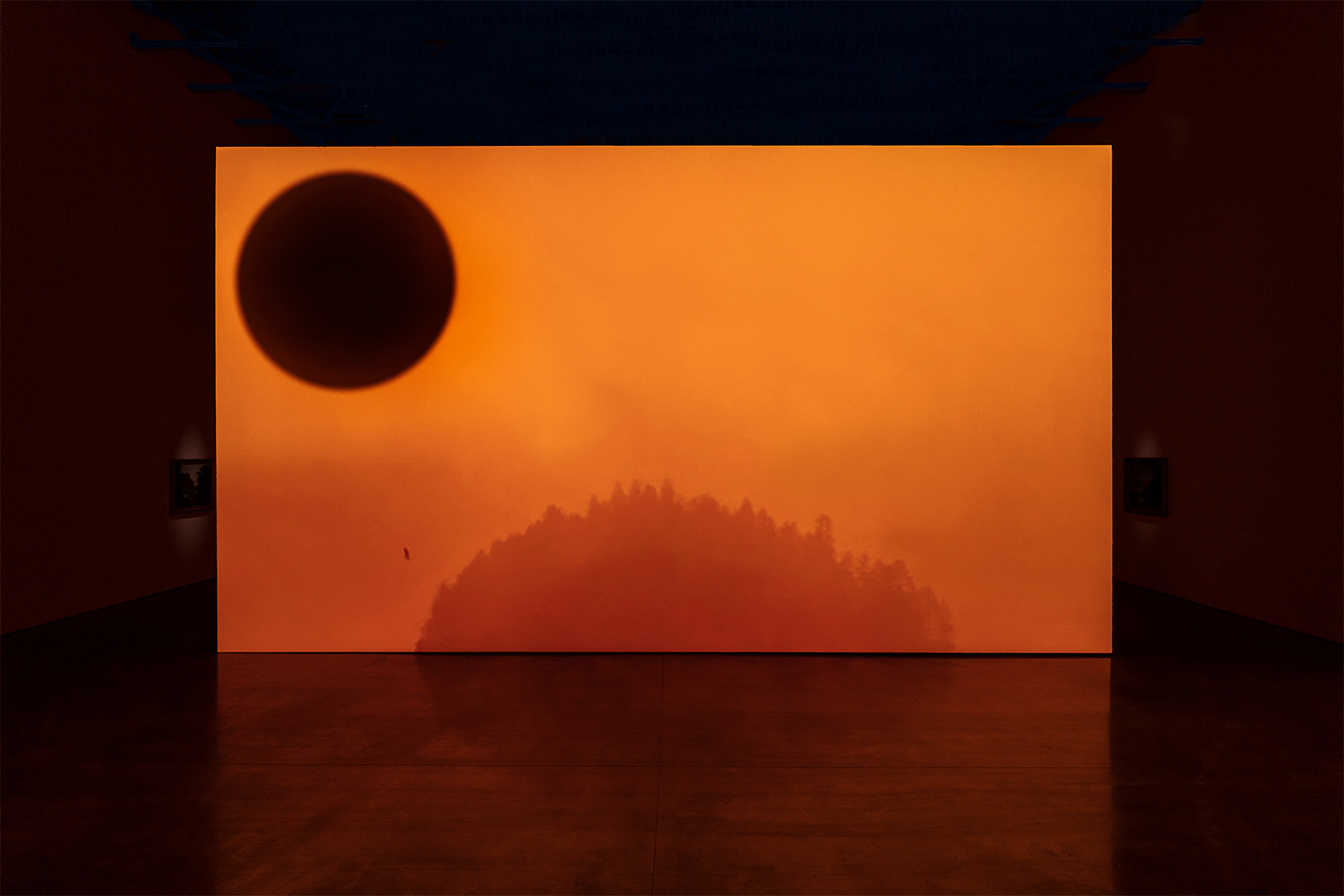

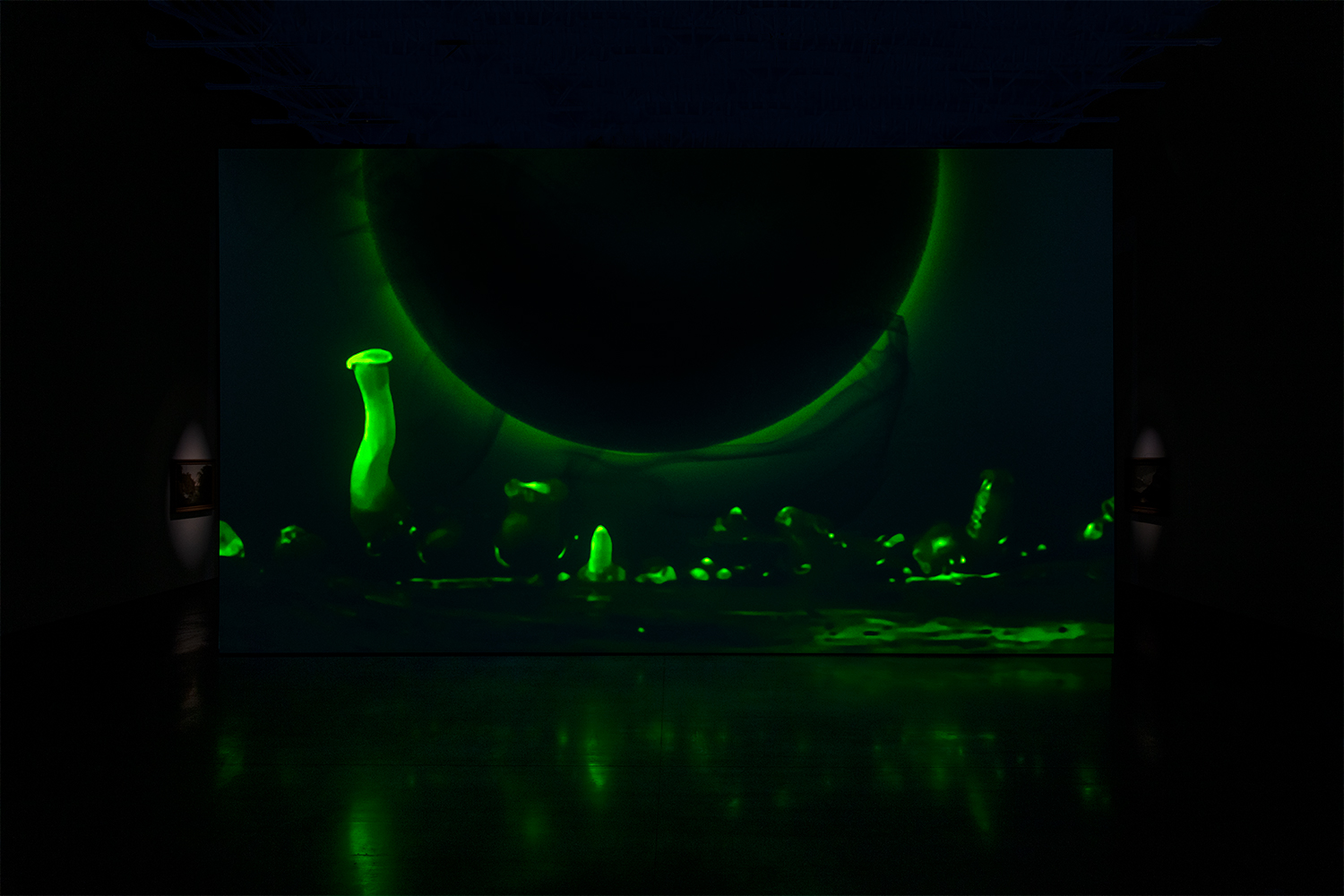

Rachel Rose, “Enclosure”. Exhibition view at Gladstone Gallery, New York, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, “Enclosure”. Exhibition view at Gladstone Gallery, New York, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, “Enclosure”. Exhibition view at Gladstone Gallery, New York, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, “Enclosure”. Exhibition view at Gladstone Gallery, New York, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, “Enclosure”. Exhibition view at Gladstone Gallery, New York, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, “Enclosure”. Exhibition view at Gladstone Gallery, New York, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, “Enclosure”. Exhibition view at Gladstone Gallery, New York, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, “Enclosure”. Exhibition view at Gladstone Gallery, New York, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

With “Enclosure,” her latest exhibition at Gladstone Gallery, New York, Rachel Rose takes us back to a moment in time when everything changed: our relationship with Nature, our relationship with each other, and our relationship with Mystery. This happened the day someone had the idea to claim ownership over common parcels in the English countryside. Since feudal times in England, people were guaranteed access to the land in perpetuity, as expressed by “The Charter of the Forest” made official in 1217. But progressively, during the sixteenth century, the clergy, the crown, and the wealthy, seeing rapid industrialization progress abroad and inland, sought to make the most of the land by controlling its agricultural production. They drew parcels — enclosures — to privatize the common land. This shift in access to economic resources would shape English society forever, resulting in loss of public spaces, damaged ecology, and displaced populations — a total “robbery” of the working class argues historian E. P. Thompson. On a symbolic level, it also spelled the end of the Nature-Human dynamic gift exchange described by Lewis Hyde. Now that agricultural benefits are locked as a capital, energy and meaning stop circulating and humanity gets deprived of its own potential. The advent of enclosures also had a tremendous impact on the place of women in society: demoted from their initial role of community benefactors and leaders, they went on to become in many cases either witches or prostitutes. Rachel Rose revisits the dawn of this great shift through a film, paintings, and sculptures. Each aspect of the exhibition speaks to this key moment in different ways, looking at the dramatic history, the impossible future, and the present reality that we inherited.

Rachel Rose, Enclosure, 2019.

Still from the video.

Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, Enclosure, 2019. Still from the video. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, Enclosure, 2019. Still from the video. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, Enclosure, 2019. Still from the video. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, Enclosure, 2019. Still from the video. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, Enclosure, 2019. Still from the video. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, Enclosure, 2019. Still from the video. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, Enclosure, 2019. Still from the video. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

The centerpiece of “Enclosure” is a thirty-minute-long film that revisits the juncture in history when a feudalist society transformed into a capitalist one. Anxious because of the new Enclosure law, a village population is exploited by a cultlike clan, their leader Jaccko and their spy Recent. The cult convinces the village’s farmers to sell them their land for next to nothing in exchange for a fake currency. The film’s scenography and photography convey a sense of harmony too pure to remain untouched, pregnant with dramatic potential. In that sense, the film reminds us of Polanski’s Tess and Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, where heavenly settings are fertile ground for catastrophe. Paradise is lost. We are the Lucifers of Mother Nature. Between dialogues, a celestial body looms, a sentient stain marking mankind’s dark fate. While the film unfolds its historical drama, a curation of seven British Romantic paintings (Gainsborough, Wright, Palmer, and Constable) displayed all around the central film celebrates the joy of looking outside the city, toward pastoral communities, where work might celebrate the supernatural powers of a harvest moon. These paintings remind us of our sacred bond with the land. Placed in a circle, they form the ring of an obsolescent dream now echoing in the universe.

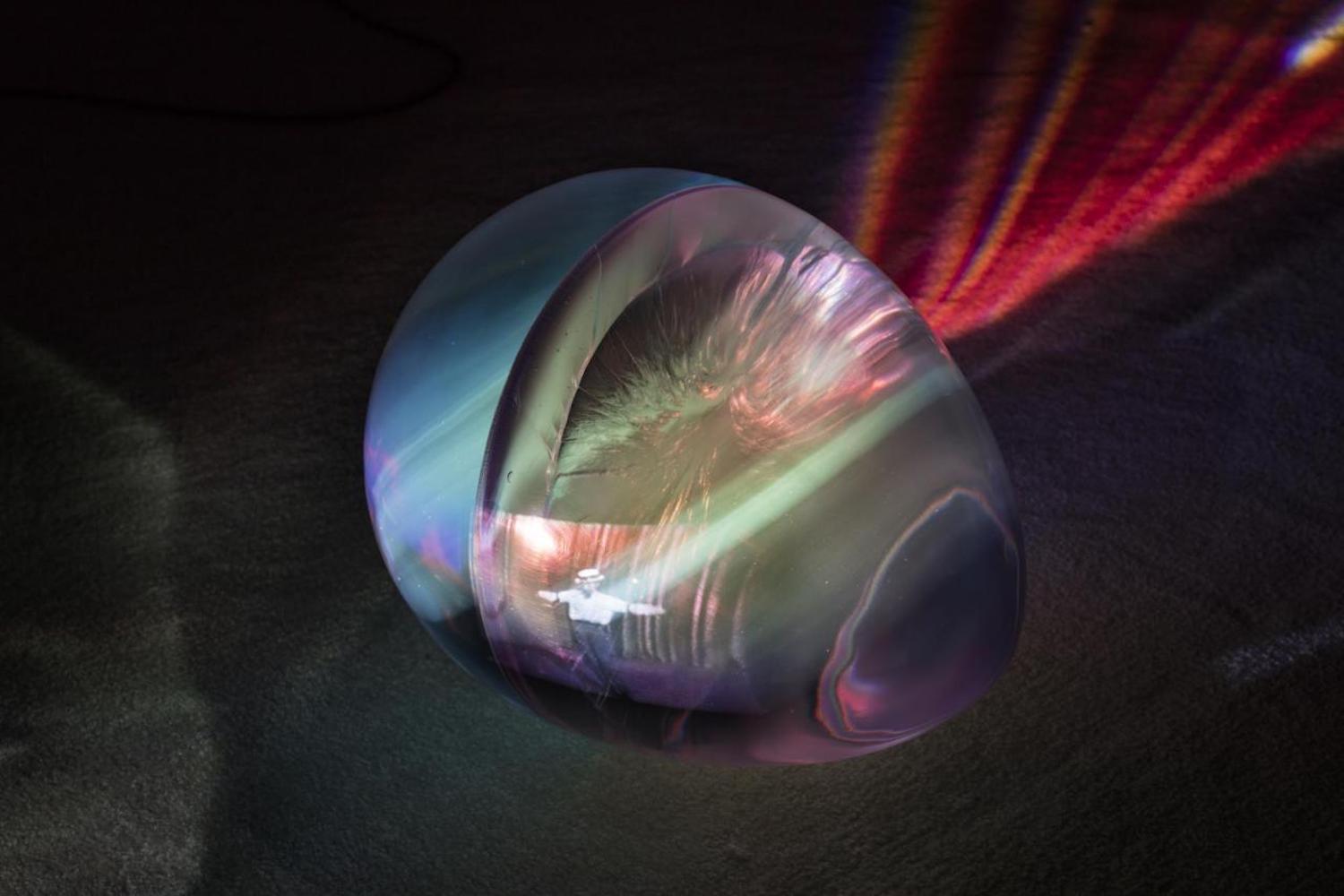

Rachel Rose, Burl Egg 1, 2021. Burl Egg and blown glass. 43,2 x 43,2 x 30,5 cm. Photography by Daniel Greer. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, Calcite (88 million BC), 2021.

Calcite with pyrite powder Cretaceous epoch rock, and glass. 28 x 25,4 x 23 cm.

Photography by Daniel Greer. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, Loop (30 million BC), 2021. Gogotte Oligocene epoch rock, and glass.

22 x 19 x 28 cm.

Photography by Daniel Greer. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, Loop (150 million BC), 2021. Flourite Jurassic epoch rock, glass. 30 x 30 x 12 cm. Photography by Daniel Greer. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, Colore (1796), 2021.

Iridescent pigment, color pigment, and metallic powders on an ink jet print of Joseph Wright of Derby’s Derwent Water, with Skiddaw in the distance ca. 1796. 56,2 x 62,9 cm; 82,6 x 88,9 x 2,5 cm framed. Photography by Daniel Greer. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, Colore (1786), 2021.

Iridescent pigment, color pigment, and metallic powders on an ink jet print of Joseph Wright of Derby’s Dovedale ca. 1786. 63,8 x 71,4 cm; 90,2 x 97,8 x 2,5 cm framed. Photography by Daniel Greer. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, Colore (1780), 2021.

Iridescent pigment, color pigment, and metallic powders on an ink jet print of Joseph Wright of Derby’s Matlock Tor by Moonlight ca. 1780.

63,5 x 62,5 cm; 89,5 x 88,9 x 2,5 cm framed.

Photography by Daniel Greer. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Rachel Rose, Colore (1825), 2021.Iridescent pigment, color pigment, and metallic powders on an ink jet print of John Constable’s Hampstead Heath ca. 1825. 29,5 x 31,7 cm; 55,9 x 57,8 x 2,5 cm framed. Photography by Daniel Greer. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York. © Rachel Rose.

Also placed throughout the gallery are sculptures variously titled Loop, Calcite, and Burl Egg, made with rocks from prehistoric times, which introduce a different magnitude of temporality, adding a sense of mystery and the supernatural to the exhibition. On a different floor, Rose presents a manipulation of the exact same British paintings, as if she placed the aforementioned mysterious orb over them and let them soak up the nefarious ink. Rose’s paintings appear contaminated, transformed by the wicked entity. This room is an alternate space and time to the previous gallery: these paintings portray the flip side of Romantic Nature, which is the reality that we live in today.