“The idealist aesthetic uses the idea of a static, ‘everlasting’ nature, and an a priori assumption of an existence of a static, ahistorical man, with his assumed static and ‘everlasting’ viewing of this nature.” — Władysław Strzemiński1

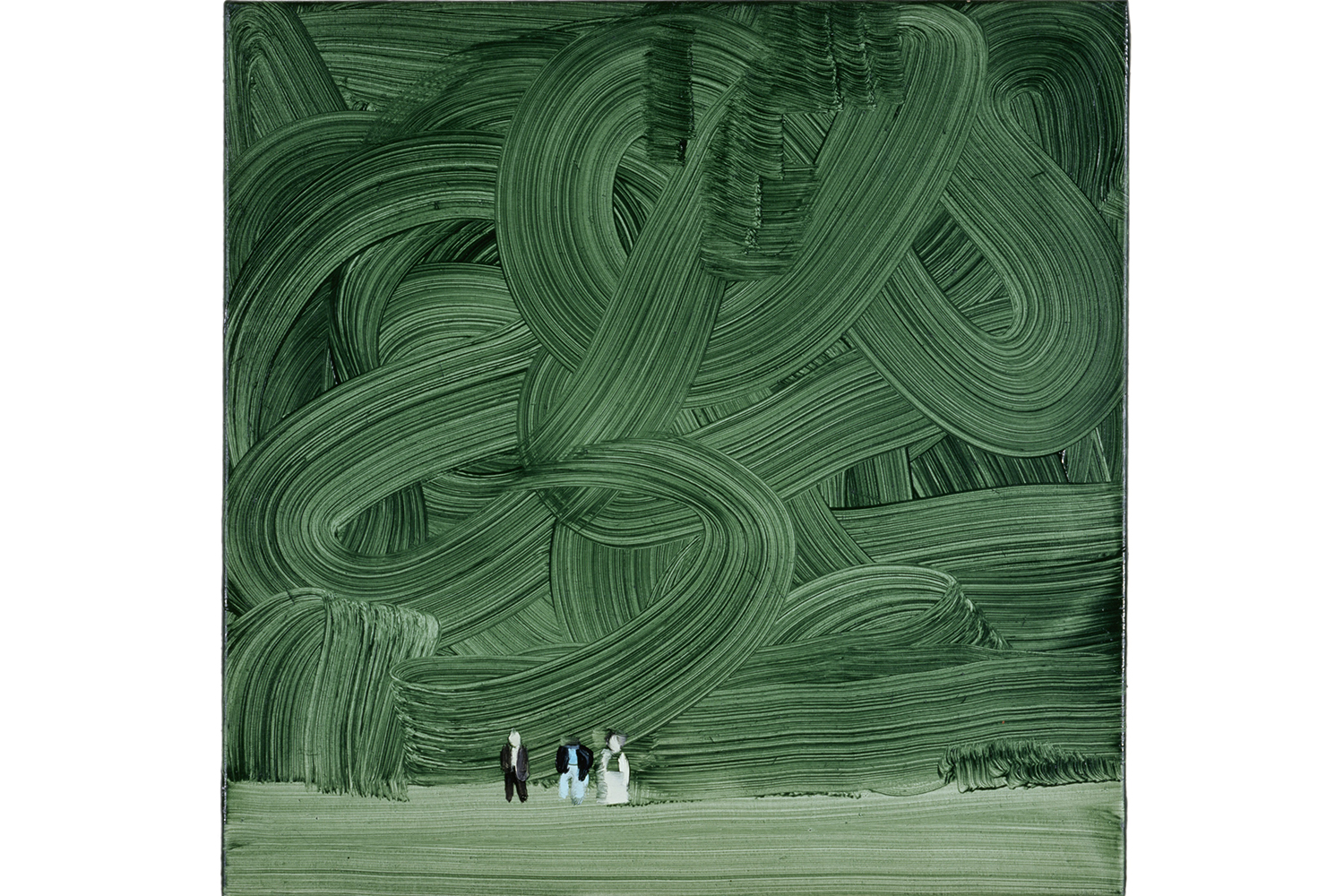

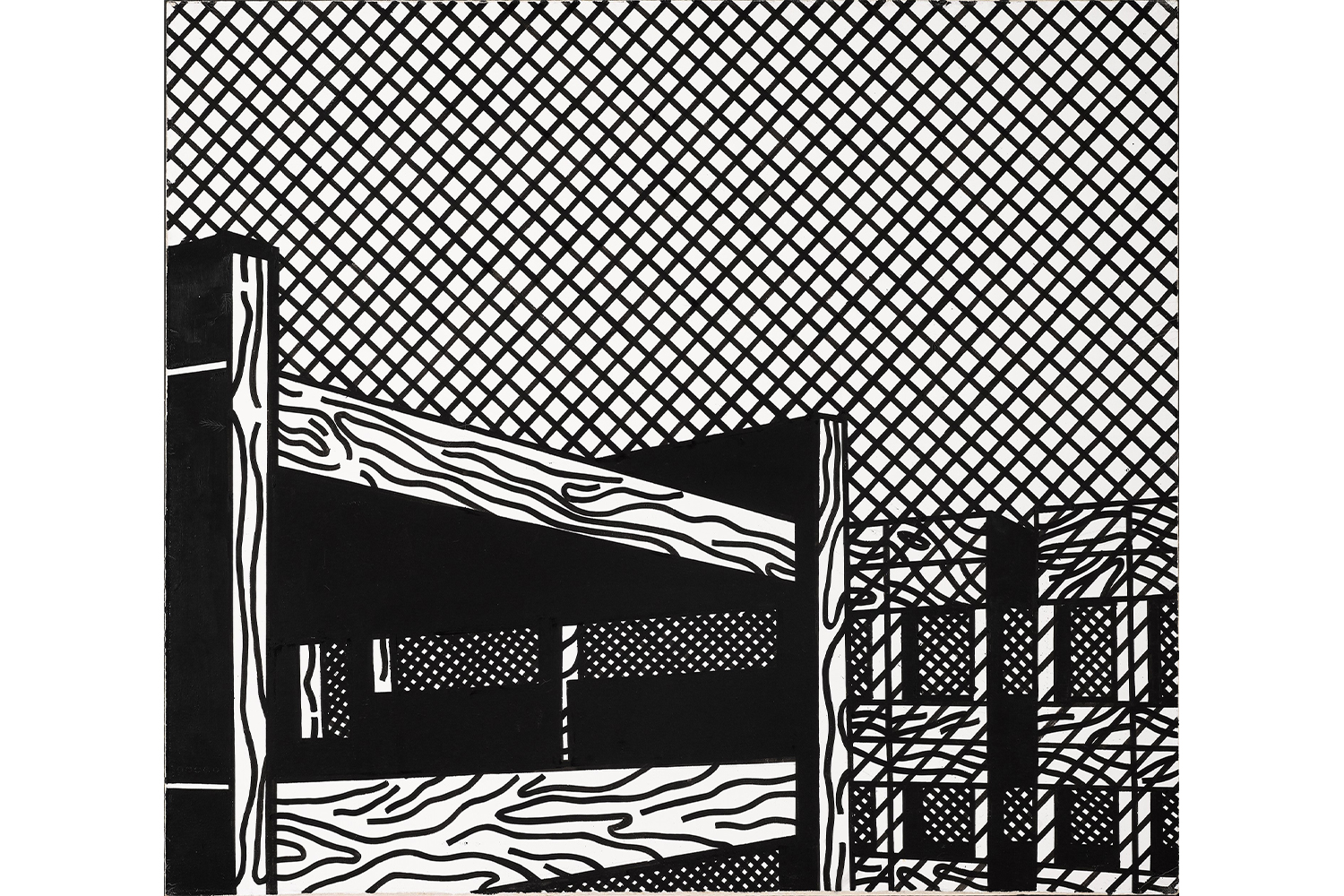

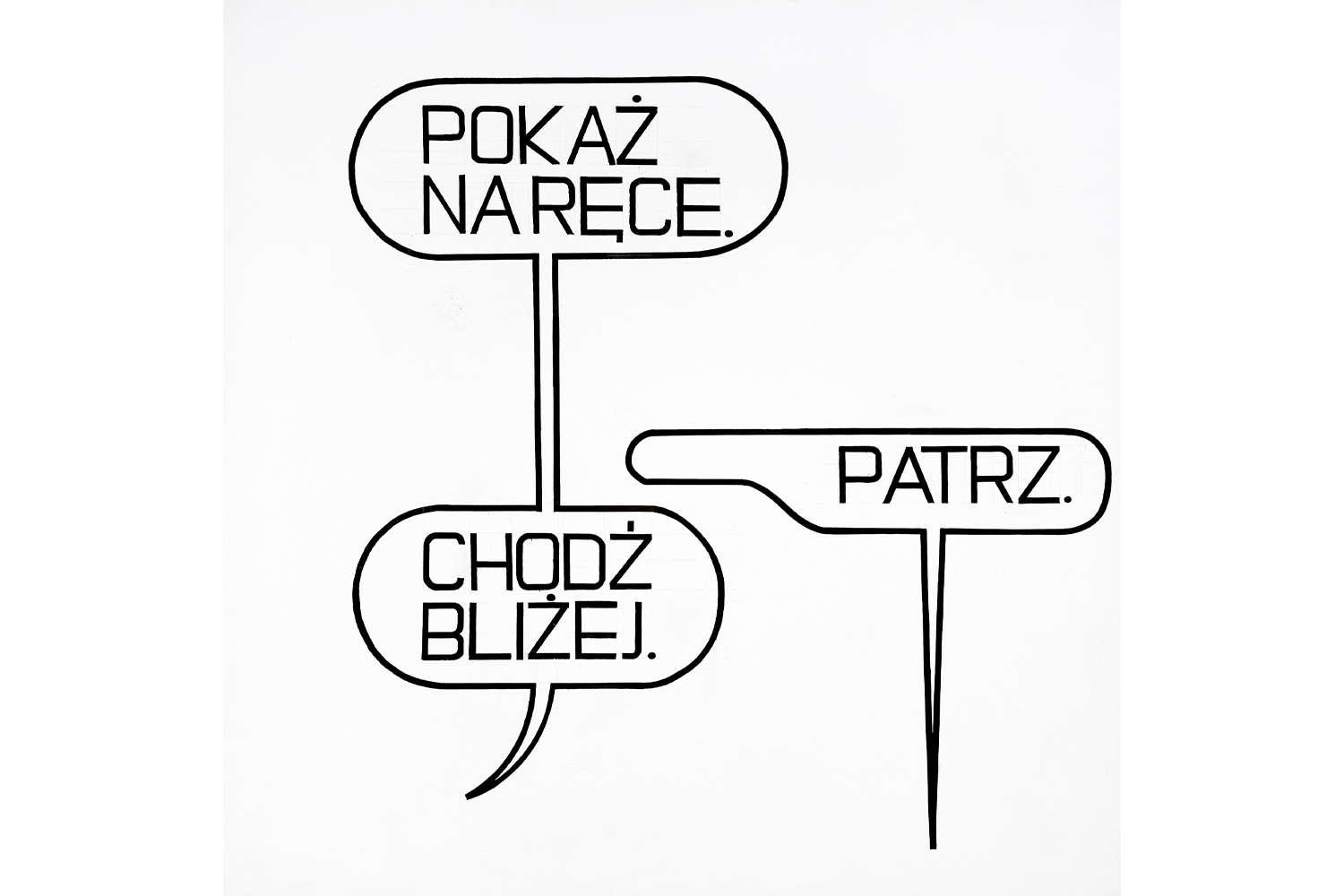

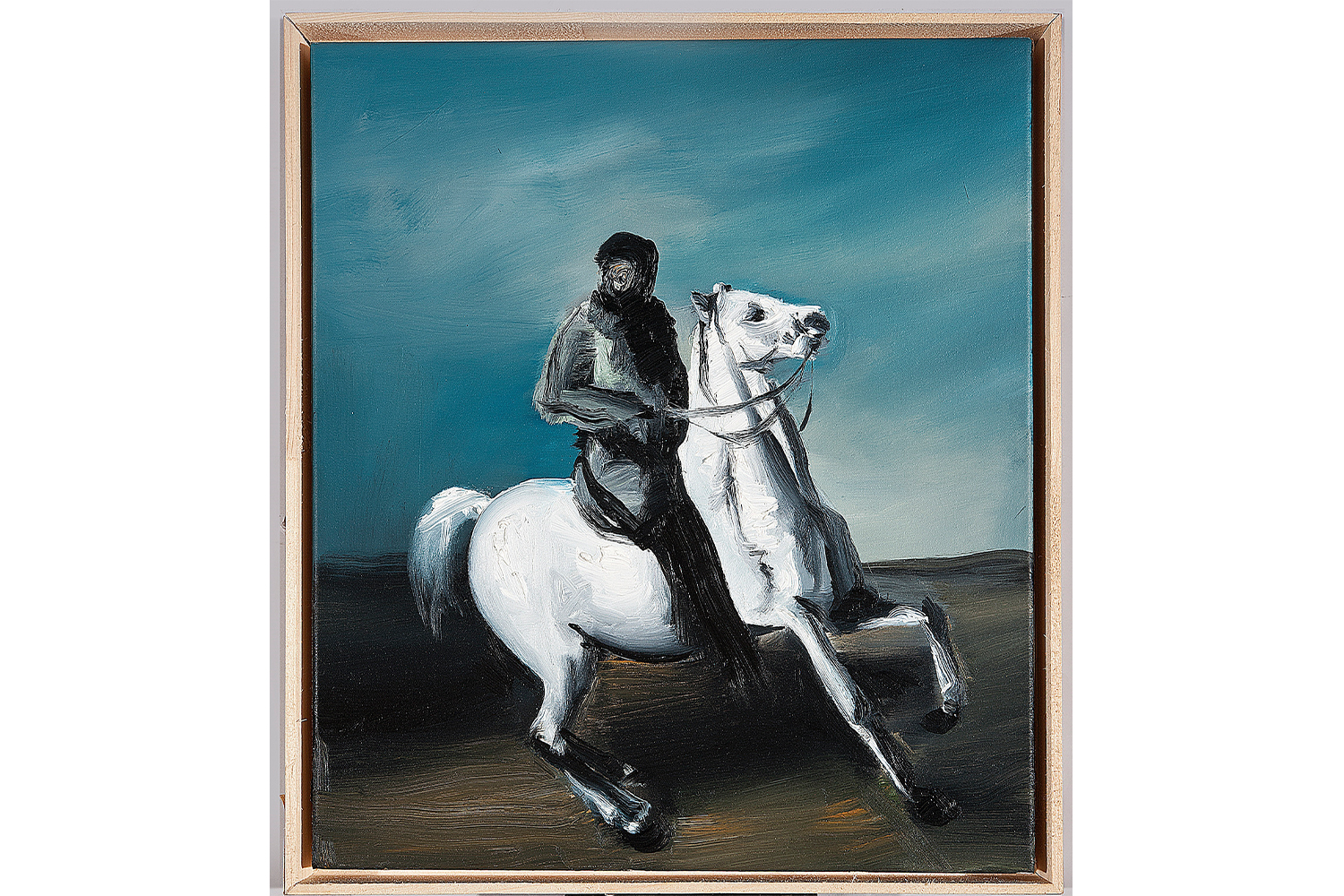

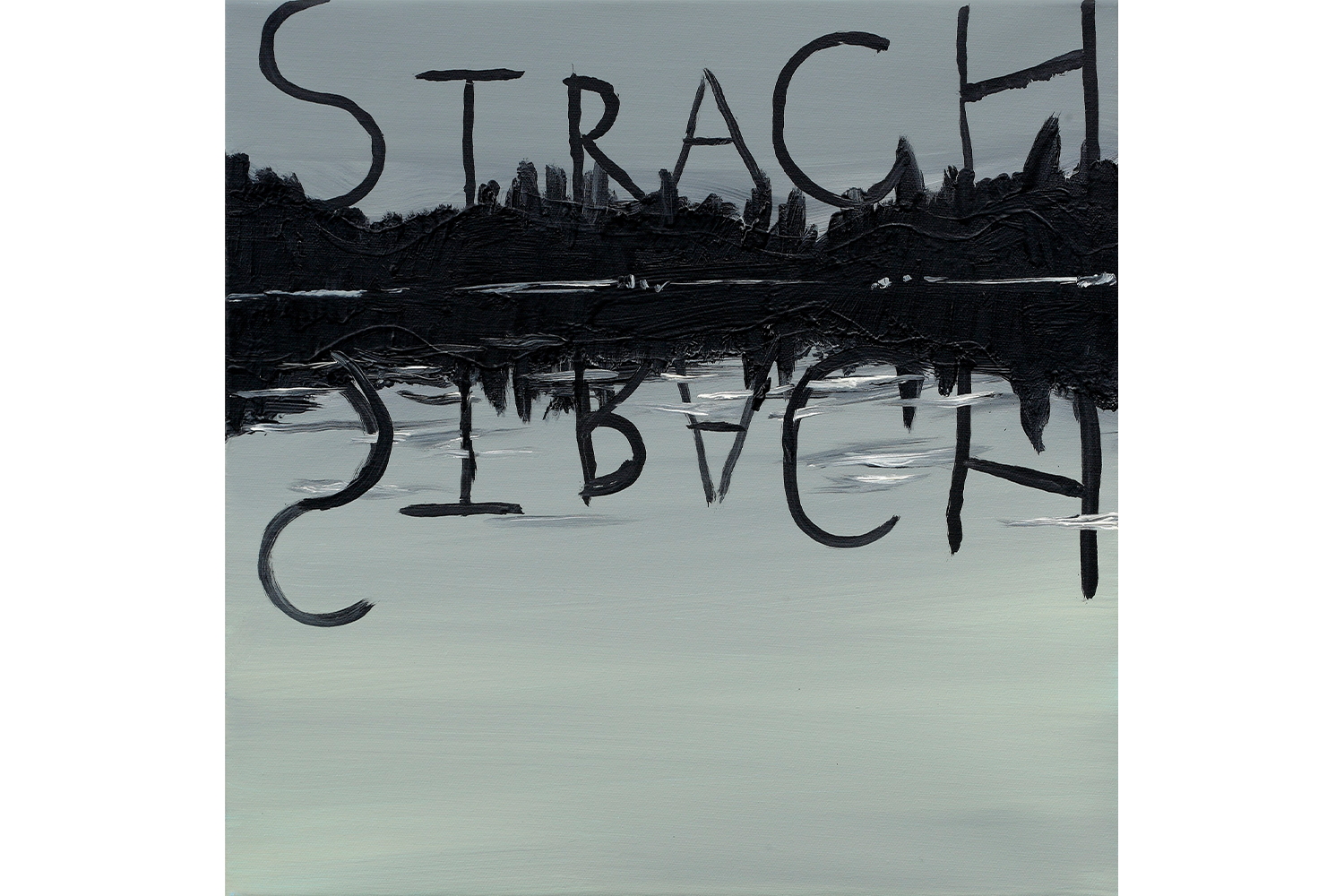

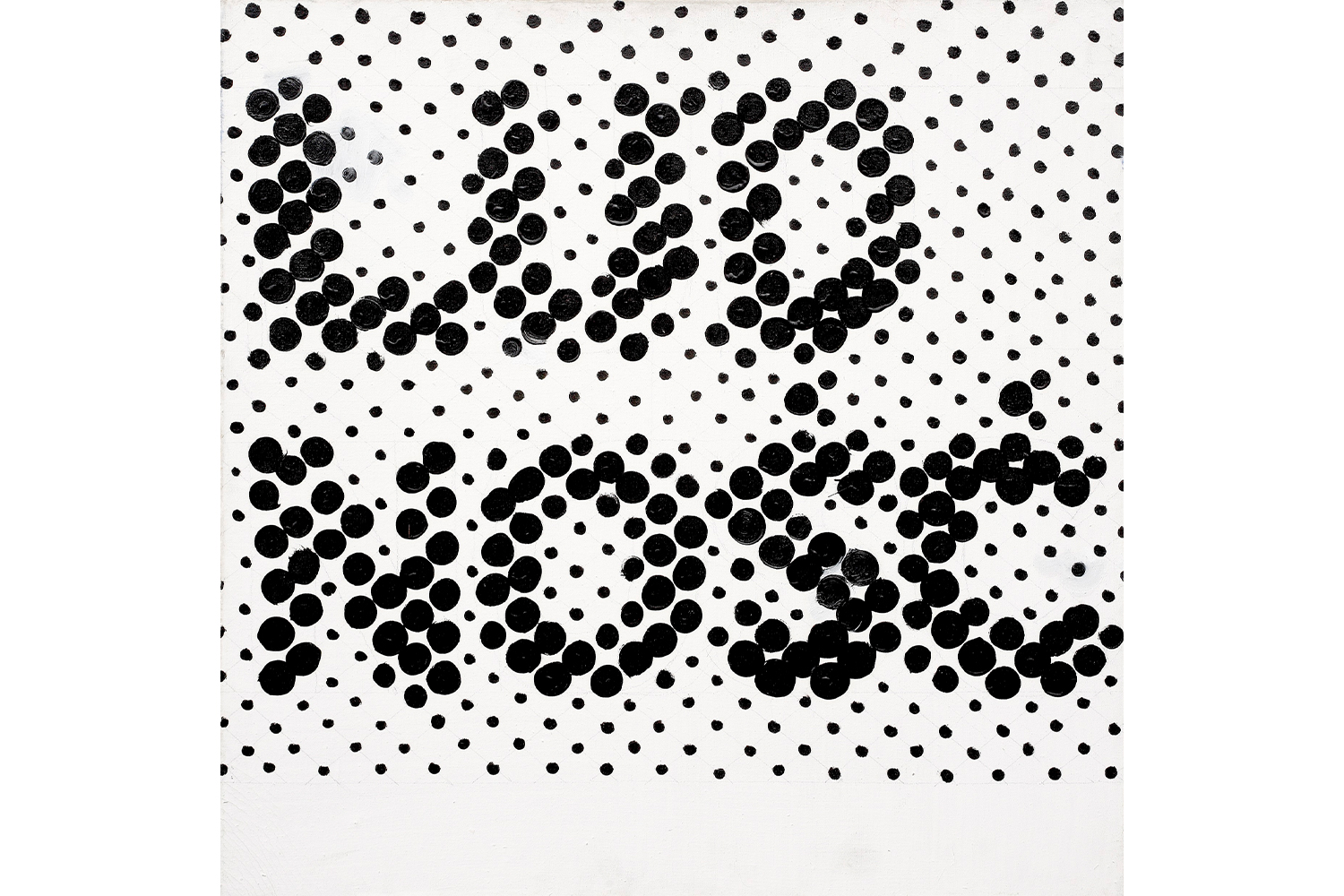

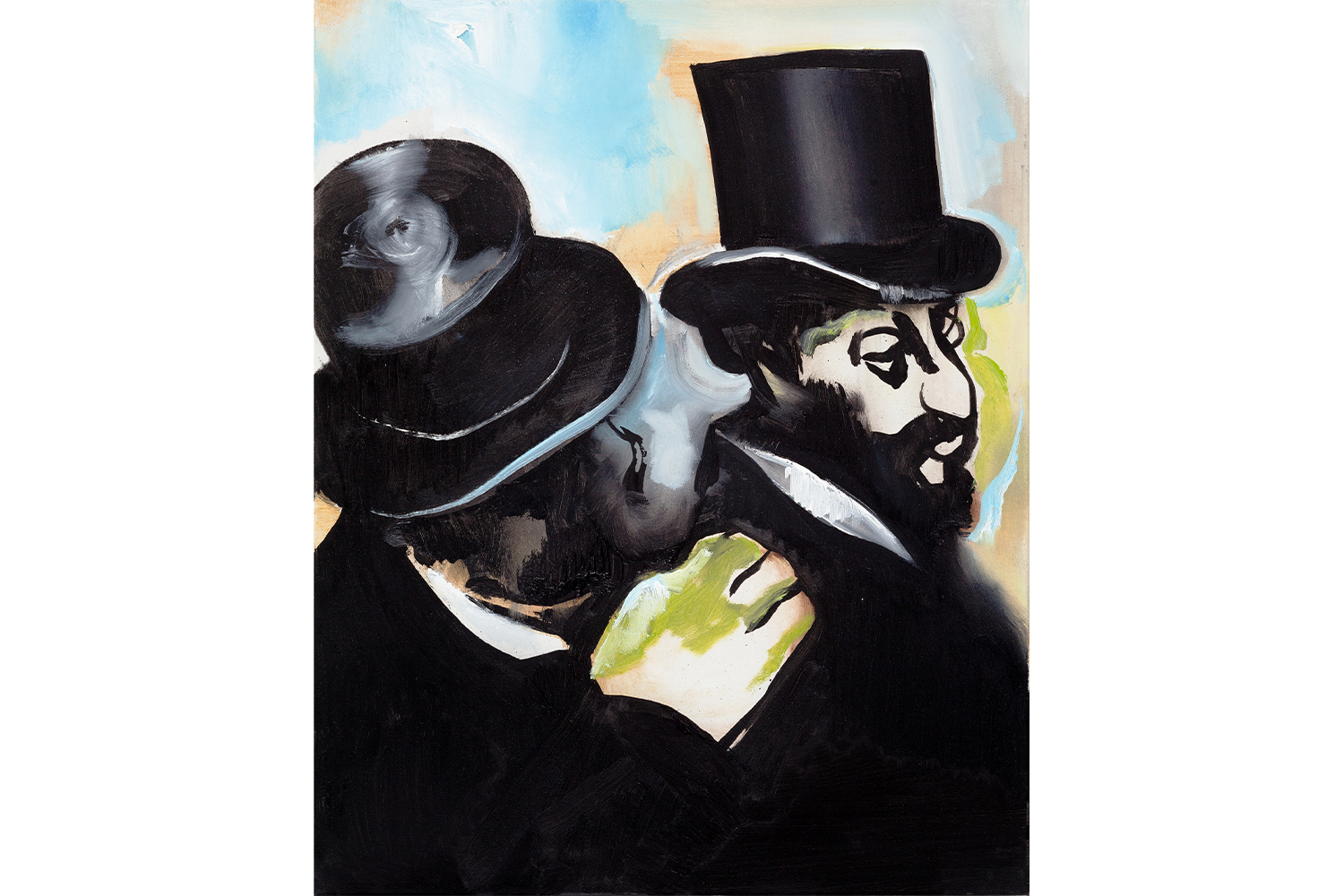

Certain of its exceptional role in history, each generation firmly believes itself to be living in apocalyptic (or at least “interesting”) times. Even though one may be aware that the sense of uniqueness given by this conviction is but an illusion, it is still hard to shake it off living in contemporary Poland, where messianic myths — remade for modern, nationalistic policies — reign supreme. Alongside a personal favorite, the evergreen “Polish Mother,” a more universal one thrives: the myth of the Polish landscape, a land that supports, nourishes, and provides a view so wondrous and pure that it motivates countless artists to commemorate it in words, images, and notes. Curated by Adam Szymczyk, Wilhelm Sasnal’s retrospective in Warsaw offers a very different approach, aimed at unveiling what lies beneath the surface. Balancing between realism and abstraction, the artist unveils the processes during which an image mutates into an icon and a sight morphs into a symbol.2 The landscape portrayed by Sasnal has witnessed too many years of atrocity and injustice to stay idyllic; instead, it resembles the eerie and sinister scenery described in a poem by Andrzej Szmidt, from which the show takes its title.3 POLIN, the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, built on the rubble of the Warsaw Ghetto, is an adequate host for Sasnal’s longtime struggle with Polish mythology and the heroic self-image of Poles.4 His characteristic, concise manner is a perfect tool for highlighting the reductive filters we use to observe and make sense of the world.

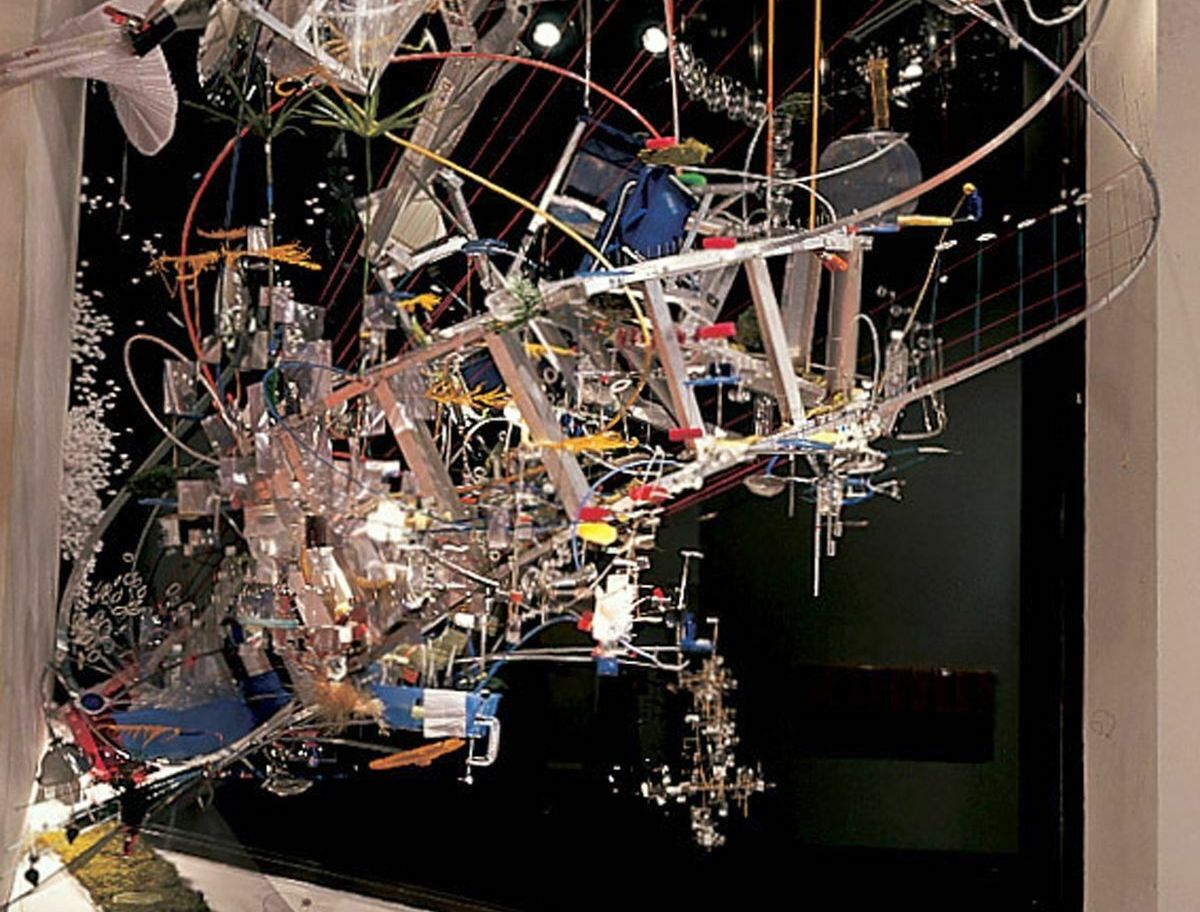

The show’s scenography, conceived by Johanna Meyer-Grohbrügge, transcends the usual ambitions of the “white cube”: the museum space, thoroughly covered in reflective, metallic sheets, offers immersion instead of transparency. Hence, the exhibition space may serve as a metaphor for a collective unconscious: an area where memories, facts, and affect coexist. Viewers, whose figures are mirrored in the museum walls next to the paintings, seem to be equal protagonists of this strange imaginarium — a sphere that usually remains hidden and inaccessible but brought to light in the rooms of POLIN.

This ambiguous relationship between the seen and seer is cleverly summed up in Untitled (2017) — hanging next to the now iconic Shoah (2003) — a work depicting a giant, greenish eye, its pupil consuming forest scenery. The artist himself aptly describes this work in a hand-drawn exhibition guide (which itself is a clever visual commentary on the show): “The eye swallows the landscape; the landscape gouges the eye.” This description — hinting at a struggle between the seen and the seer — evokes the thoughts and illustrations in the Theory of Vision, a treatise by the Polish avant-gardist Władysław Strzemiński. Strzemiński (although not mentioned by the artist or the curator explicitly), who “saw the world of form and color in an all-embracing connection to the totality of human activity,”5 advocated for the active role that art can play in shaping the visual consciousness of its admirers. The same seems to be true for Sasnal. “Such a Landscape” proves that a seemingly unbiased view is indeed heavy with clichés and automatisms, and, after visiting the exhibition, these failings are no longer possible to ignore. Nevertheless, admitting that they are still there is the first step in working through them.