Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Installation view at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Installation view at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Installation view at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Installation view at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Installation view at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Installation view at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Installation view at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Installation view at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Installation view at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Installation view at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

When shortlisted for the 2021 Turner Prize, the Belfast-based Array Collective immediately had the idea to realize something that could involve not only its eleven visual artist and activist members, but also as many people as possible: friends, other artists, communities, allies.

In the Irish Decade of Centenaries, this year marks the introduction of the Government of Ireland Act, when six Ulster counties were partitioned from the others, thus forming Northern Ireland. The resulting religio-ethnic division created a strong political dichotomy with well-known consequences, including obscuring many other identities as well as unaddressed social emergencies and rights.

In contrast, what characterizes the Belfast art scene is a spirit of pure collaboration among the artist-led organizations founded in late ’80s and ’90s, many still active despite being forced to move away from the city center due to gentrification and unscrupulous town planning. Among Belfast’s artist studios, Array, established in 1994, has since 2016 hosted a collective of visual artists with different individual practices, who all share common social and political interests such as queer liberation, women’s rights, mental health, gentrification, the Irish language, and British colonialism. Their work takes the form of protests, performances, workshops, and symposia, all with a humorous touch that manages to blur the usual history of Northern Ireland. Interrogating contemporary anxieties with characters from Irish folklore, they address the trauma of a post-conflict society with a totally unique approach.

The homemade banners and costumes they march with provoke joyful reactions as well as questions and new perspectives. For instance, at the International Women’s Day in March 2018 they paraded with a carved stone figure — Sheela na Gig — with an exaggerated vulva, representing ancient Ireland’s right to choose; or, for the 2019 Belfast Pride Parade, they developed three characters from folk tales and personal experiences: the Sacred Cow, the Long Shadow, and the Morrigan. These characters were realized for As Others See Us, commissioned for the show “Collaborate!” at Jerwood Arts in London in 2019.

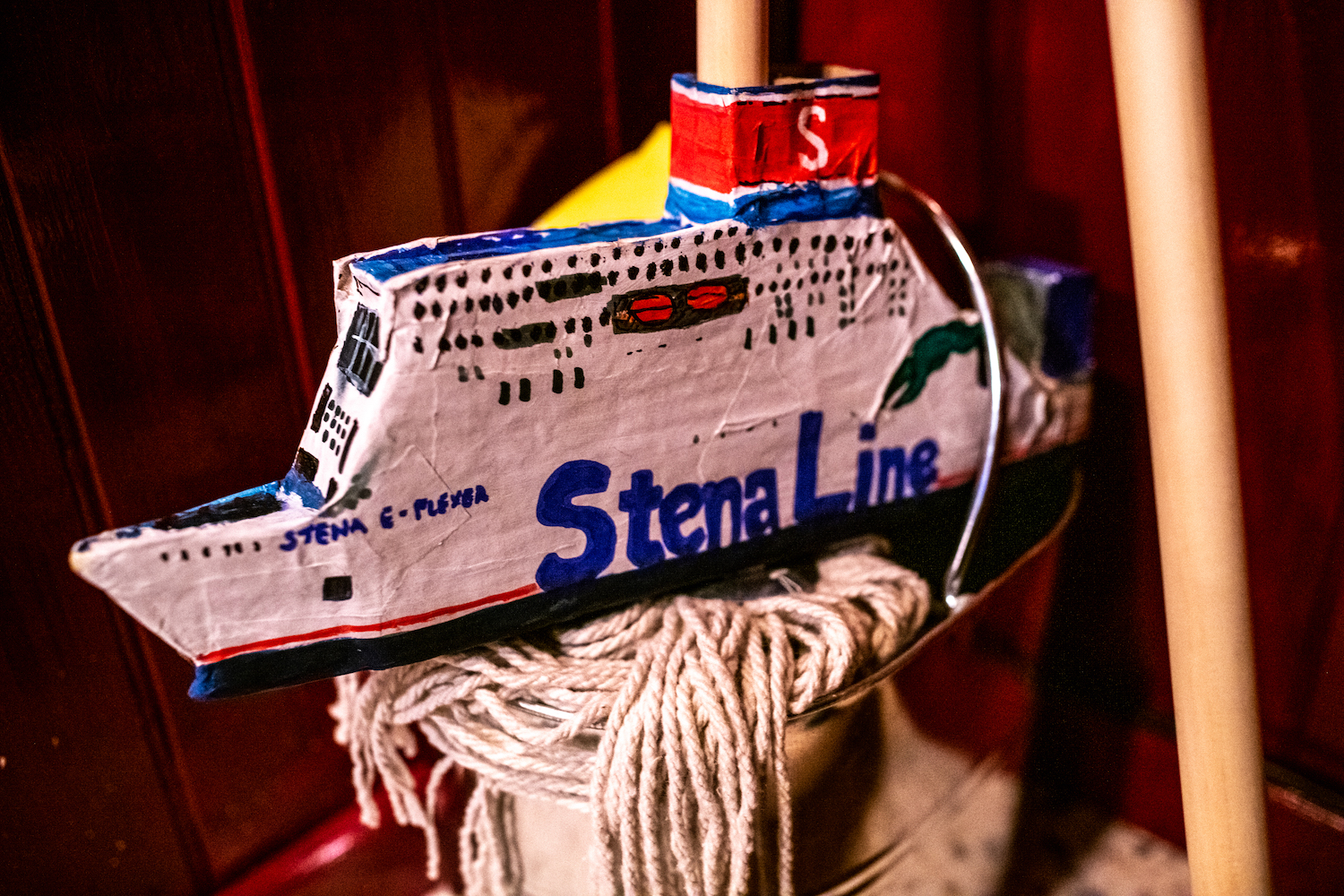

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Detail of the installation at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Detail of the installation at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Detail of the installation at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Detail of the installation at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Detail of the installation at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Detail of the installation at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Detail of the installation at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Detail of the installation at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Detail of the installation at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

Array Collective, The Druithaib’s Ball, 2021. Detail of the installation at Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Conventry. Photography by Garry Jones. Courtesy of the artists and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry.

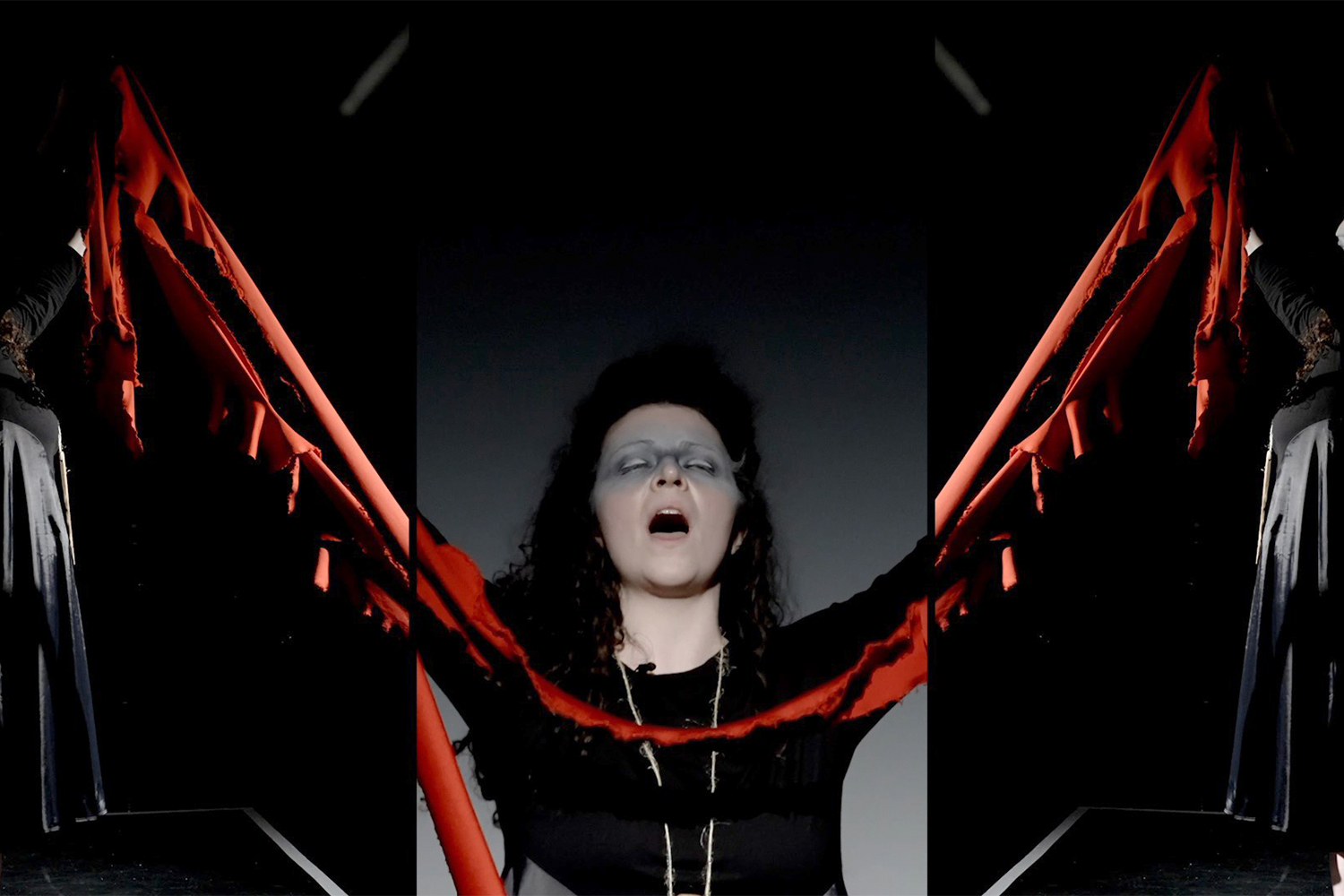

In July 2021, the collective decided to expand the idea of creating characters combining Irish folklore, pre-Christian symbols, and modern identities. They organized an event called The Druithaib’s Ball at the Black Box in Belfast, in which all those invited took part in a grotesque performance wearing wild costumes. This wake, intended to commemorate the centenary, was celebrated in Belfast, then transported to the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum in Coventry, England, for the final show of the Turner Prize in the form of an immersive installation in the welcoming atmosphere of a síbín — the Irish name for unlicensed public houses. Before entering, visitors first walk through a room with a dusk-to-dawn light in which a circle of flagpoles — without flags — recalls ancient Irish ceremonial sites, and where the door of the illicit pub is set in a curved wall totally covered by photos of Neolithic architecture. Once inside the síbín, a warm, almost “at home” atmosphere for those familiar with these places, pervades every corner. It is possible to sit in booths or on bar stools under a floating roof made out of banners, and watch a three-channel video filmed at the event in Belfast or a thirty-five-minute montage from the Northern Ireland Screen’s Digital Film Archive on an analog TV monitor. Exiting the pub the final object of the show is a banner that commemorates the underrepresented identities of Northern Ireland with the text “The sequin foot of Ulster ~ Cos fheimineach agus aiteach Uladh” (The feminist and queer foot of Ulster), followed by “One Hundred Years of Solitude.”

Array Collective, The Druthaib’s Ball, 2021. Film still. Performer: Rosa Tralee. Courtesy of the artists.

Array Collective, The Druthaib’s Ball, 2021. Film still. Performer: Vasiliki Stasinaki. Courtesy of the artists.

Array Collective, The Druthaib’s Ball, 2021. Film still. Performer: Cleamairí Feirste. Courtesy of the artists.

Array Collective, The Druthaib’s Ball, 2021. Film still. Courtesy of the artists.

Array Collective, The Druthaib’s Ball, 2021. Film still. Performer: Méabh Meir. Courtesy of the artists.

Array Collective, The Druthaib’s Ball, 2021. Film still. Performers: Ban Bídh and Long Shadow. Courtesy of the artists.

Array Collective, The Druthaib’s Ball, 2021. Film still. Performer: Rosa Tralee. Courtesy of the artists.

Array Collective, The Druthaib’s Ball, 2021. Performance. Performer: Richard O’Leary. Photography by Ciara McMullan. Courtesy of the artists.

Array Collective, The Druthaib’s Ball, 2021. Performance. Performer: Vasiliki Stasinaki . Photography by Ciara McMullan. Courtesy of the artists.

Array Collective, The Druthaib’s Ball, 2021. Performance. Performer: Trumpa Fáda. Photography by Ciara McMullan. Courtesy of the artists.

Although the installation may evoke prestigious precedents such as Edward Kienholz’s renowned Roxys (1960–61), or Liquid Diet (1989/2006) by Mike Kelley — based on American Irish folklore and exhibited in Belfast in 2014 — it definitely achieved its purpose by not positioning the viewer in a discomfort zone but into a place of meaning “where social hierarchies are temporarily broken, through satire, celebration, and chaos.” And it is for all these reasons that Array Collective rightfully won the prestigious Turner Prize, never given to Northern Irish artists until today.