Cajsa von Zeipel. Exhibition view at Rubell Museum, Miami, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Rubell Museum, Miami.

Cajsa von Zeipel. Exhibition view at Rubell Museum, Miami, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Rubell Museum, Miami.

Cajsa von Zeipel. Exhibition view at Rubell Museum, Miami, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Rubell Museum, Miami.

Cajsa von Zeipel, A theory of feline aesthetics, 2021.

Cajsa von Zeipel, I <3 New York, 2019.

Aqua resin, acrylic nails, artificial sushi, baby Pug stress reliever, cord organizer- shoestring, fiberglass, glass eyes, hardware, heart keychain, hot pink lacquer pants, I <3 NY dog clothes, large wine glass, paracord patches (Peace out) and pins (bee, flowers, knife, decisions, and Trixie Mattel), piercings, pigmented silicone, pleaser platform heel, resin flower pedals, sewing pins, small handcuffs, stuffed animals (Cockapoo and, pomeranian puppies), styrofoam, swivel chair, T- shirt (Living my best life), transparent heart sock, tulle, white and pink faux fur, white denim, and zip ties.

149.86 x 127 x 139.70 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Cajsa von Zeipel, Fluff you, you fluffin’ fluff, 2020. Aqua resin, acrylic nails, aquarium tubing, artificial folding knife, barbed wire socks, basketball hoop, bedazzled letters “ILY”, bike cable lock, bike pump, bridle rack, car USB port, car phone mount, carabiners, crocs charms, defender Sport shield, easter Island head mug, expandable foam, fabrics, hair coils, half face respirator, hardware, 3 keychains (subway train, hey chihuahua, and metro card), lenticular, luggage tag, mini mermaid tail, nail file – FLUFF YOU, YOU FLUFFI’N FLUFF, ombre purple to pink fringe, phone case, pigmented silicone, plexiglass, 4 rubber macaroons, 2 rubber eggs, stirrup, stroller wheel, styrofoam, 2 stuffed animals (pug and St Bernard puppies), trigger point massager, 2 toy guns, tubing, vaginal dilator, wallet chain, wire hanger, wood, and zip ties. 190.50 x 132.08 x 101.60 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Cajsa von Zeipel, Fluff you, you fluffin’ fluff, 2020. Detail. Aqua resin, acrylic nails, aquarium tubing, artificial folding knife, barbed wire socks, basketball hoop, bedazzled letters “ILY”, bike cable lock, bike pump, bridle rack, car USB port, car phone mount, carabiners, crocs charms, defender Sport shield, easter Island head mug, expandable foam, fabrics, hair coils, half face respirator, hardware, 3 keychains (subway train, hey chihuahua, and metro card), lenticular, luggage tag, mini mermaid tail, nail file – FLUFF YOU, YOU FLUFFI’N FLUFF, ombre purple to pink fringe, phone case, pigmented silicone, plexiglass, 4 rubber macaroons, 2 rubber eggs, stirrup, stroller wheel, styrofoam, 2 stuffed animals (pug and St Bernard puppies), trigger point massager, 2 toy guns, tubing, vaginal dilator, wallet chain, wire hanger, wood, and zip ties. 190.50 x 132.08 x 101.60 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Cajsa von Zeipel, A theory of feline aesthetics, 2021.

Pigmented silicon, fiberglass, aqua resin, mannequin parts, synthetic yellow wig, aqua blue glass eyes, prosthetic teeth, 10 piercings, 3 pencils, 4 brushes, 13 plush cats (1 meowing, 1 breathing with batteries), cat bed, screws, 2 screwdrivers, 5 wrenches, bedazzled paw, leveler, 2 pair of Dickies pants, white camouflage bibs, 2 pair of tights, magnetic wrist belt, wooden cigarettes, fake box knife, easel, paint tray palette, 1 plastic salmon sushi, 1 drop cloth and 4 plexiglass paintings (drop cloth and plexiglass airbrushed with acrylic paint by Will Sheldon). Sculpture: 139.70 x 68.58 x 76.20 cm.

Drop cloth: 365.76 x 457.20 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Cajsa von Zeipel, Lesbians Heading Into The New Age, 2019.

Aqua resin, acrylic nails, aquarium tubing, chandelier beads, distressed denim, dog collar, fabrics, fiberglass, glass eyes, headlamp, lifeguard hoodie Miami Beach, Miami Beach sand, pigmented silicone, plaster, swivel chair, synthetic hair, tattoo mesh, timberlands, and a vibrator.

143.51 x 111.76 x 134.62 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Cajsa von Zeipel, Don’t kill my Vibe, 2020.

Silicon, fiberglass, Aqua resin, mannequin parts, metal stand, golf bag, Louis Vuitton bootleg bag, Gucci bootleg backpack, Marc Jacobs purse chain, walking stick, UPS jacket, Meryl Streep pillow, 2 stuffed animals (puppies), saddle pad, 2 stainless steel water bottles, pacifier, bathroom essentials storage bag, suitcase, luggage tag, golf tees, camouflage dog toy, toy gun, Crocs, plastic dog bone with plastic sushi, patches (“plåtluder,” ”the hustle is real,” “may,” Kim Chi and Sharon Needles, cellphone holder and cellphone case “Bitch don’t kill my vibe,” synthetic wig, glass eyes, my old bracelet, and sequin fabric. 203.20 x 190.50 x 91.44 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

I’ve always suspected there was a clear philosophical through line, linked by the vicissitudes of the absurd, from Kierkegaard to Bugs Bunny. This year’s iteration of Art Basel Miami Beach — the first “post” Covid — tended to affirm that suspicion. Let’s start with the fallacy of this desperately needed but sadly ever-receding descriptor “post.” As the various factions descended on the small Florida island city, filling its roads to capacity, the specter of Omicron cast a nervous pall upon the festivities — and underscored the disparate and opposing realities crammed therein. It was this jumble of clashing elements that lent the week’s usual carnivalesque atmosphere a somewhat nihilistic edge, likewise on ample display at the various museums, foundations, and fair venues that anchor the whirlwind week. The exhibitions and individual works that stood out did so less because they captured a clear zeitgeist, neatly distilling the turbulence of the past two years into a single legible gesture, but because they somehow were attuned to its erratic frequency, resonating to the pitch of grinding politics, markets, wealth disparities, geo-political maneuvering, and disinformation that continue to clash among us in unpredictable ways.

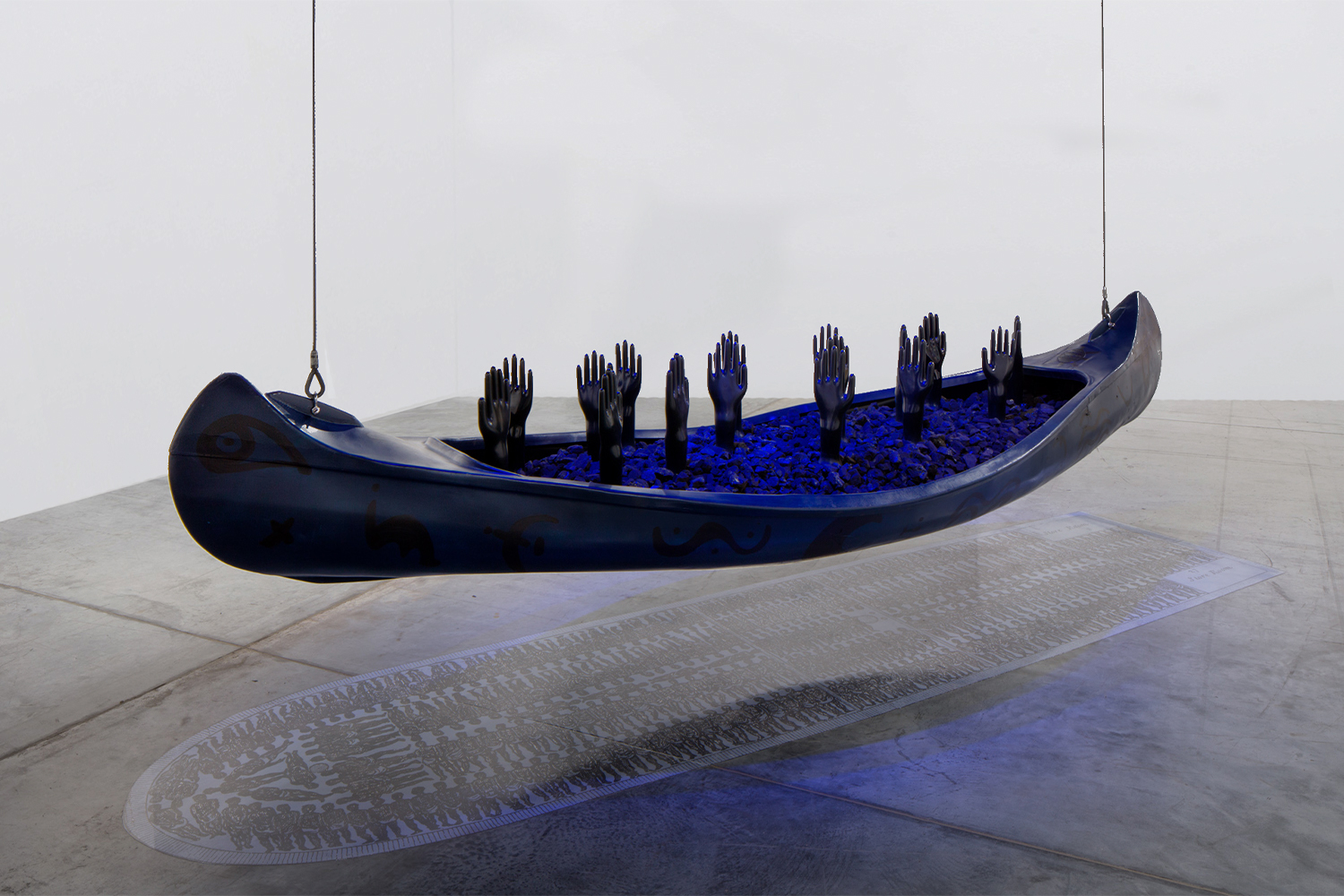

Betye Saar, Gliding into Midnight, 2019. Mixed media assemblage. 365.76 x 457.2 x 457.2 cm. Tia Collection, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles

Betye Saar, “Serious Moonlight”. Exhibition view at ICA Miami, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and ICA Miami.

Betye Saar, Mojotech, 1987. Mixed media assemblage. 193.04 x 746.76 x 40.64 cm. Photography by Robert Wedemeyer. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles.

Betye Saar, “Serious Moonlight”. Exhibition view at ICA Miami, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and ICA Miami.

Jadé Fadojutimi, “Yet, Another Pathetic Fallacy”. Exhibition view at ICA Miami, 2021. Photography by Chris Carter. Courtesy of the artist and ICA Miami.

Jadé Fadojutimi, “Yet, Another Pathetic Fallacy”. Exhibition view at ICA Miami, 2021. Photography by Chris Carter. Courtesy of the artist and ICA Miami.

Jadé Fadojutimi, A Whisper of a Decadent Twilight, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London.

ICA Miami debuted a trio of new exhibitions and showcased on its ground floor gallery a handsome array of new acquisitions, many of them generously donated by international patrons. Upstairs galleries were punctuated by Jade Fadojutimi’s colorful and athletic gestural paintings, whose slick and unctuous veneers made a compelling case for the waxing of a certain vein of pop abstraction; Hugh Hayden’s ornate and monumental sculptures offered a stark contrast in adjacent galleries. But for me, the undisputed highlight was the timely survey of Betye Saar’s immersive installations from the 1980s and ’90s. Each gathering presented itself as a self-contained galaxy, a highly personal cosmology built from ready-mades and found objects that spoke profoundly to Saar’s unwavering and trailblazing vision — both her nuanced meditation on Black identity and the African diaspora as well as her innovative use of materials and arrangement as potent aesthetic tools. The 1988 installation House of Fortune, consisting of a card table, dried palm fronds, and hanging banners with tarot card/voodoo motifs, seemed to offer a particular analogue for our uncertain future.

Ulala Imai, Gathering, 2021. Oil on canvas. Two panels, 259 x 388 cm, overall. Courtesy of the artist and Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles.

Ulala Imai, Fixer, 2021. Oil on canvas.

181.8 x 227.3 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles.

Ulala Imai, The Game: Mr. Brown and Ms. Green, 2021. Oil on canvas. 181.9 x 227.3 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles.

Arcadia Missa. View of the booth at Art Basel Miami, 2021. Photography by Thomas McCarty. Courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa, London.

Arcadia Missa. View of the booth at Art Basel Miami, 2021. Photography by Thomas McCarty. Courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa, London.

Arcadia Missa. View of the booth at Art Basel Miami, 2021. Photography by Thomas McCarty. Courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa, London.

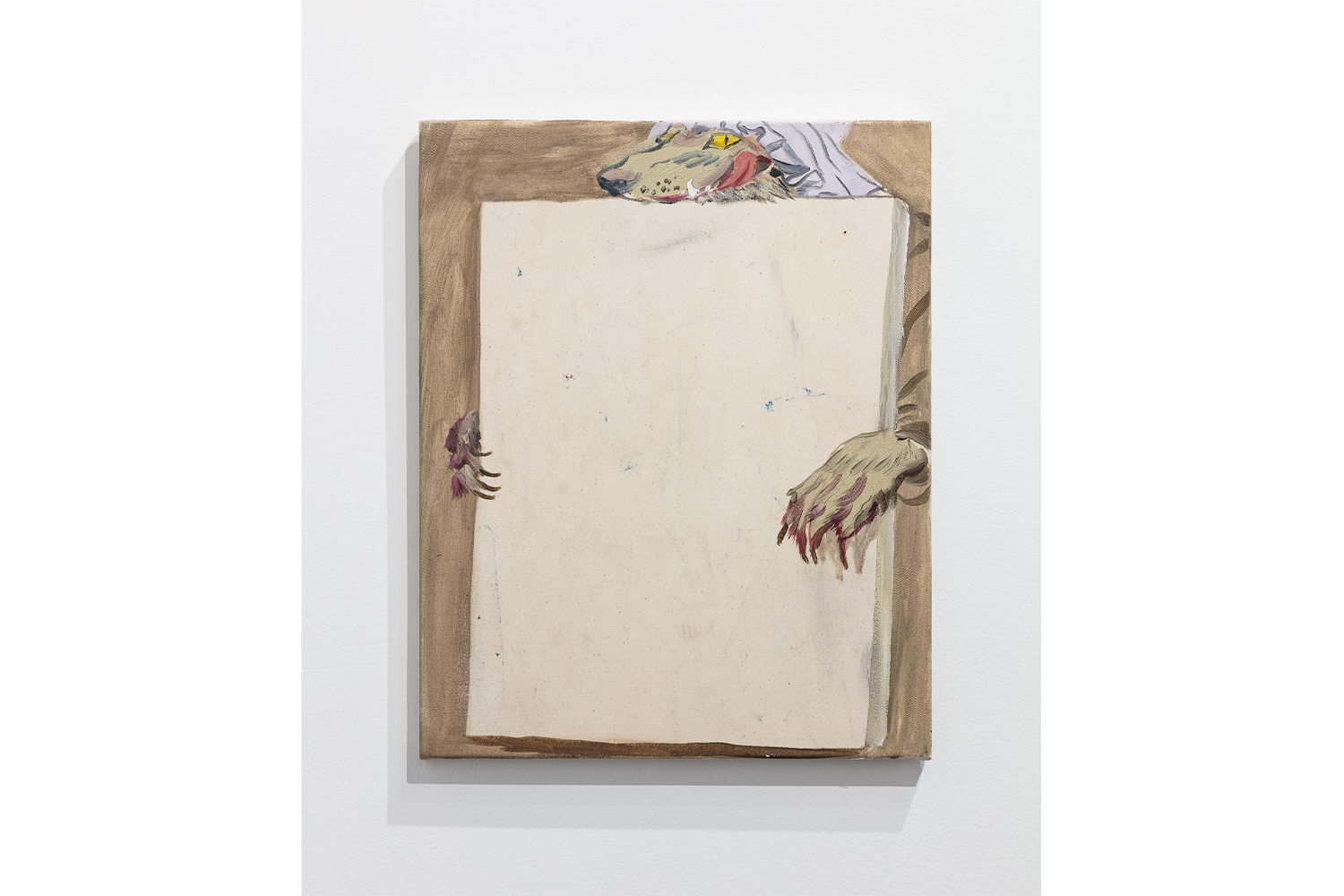

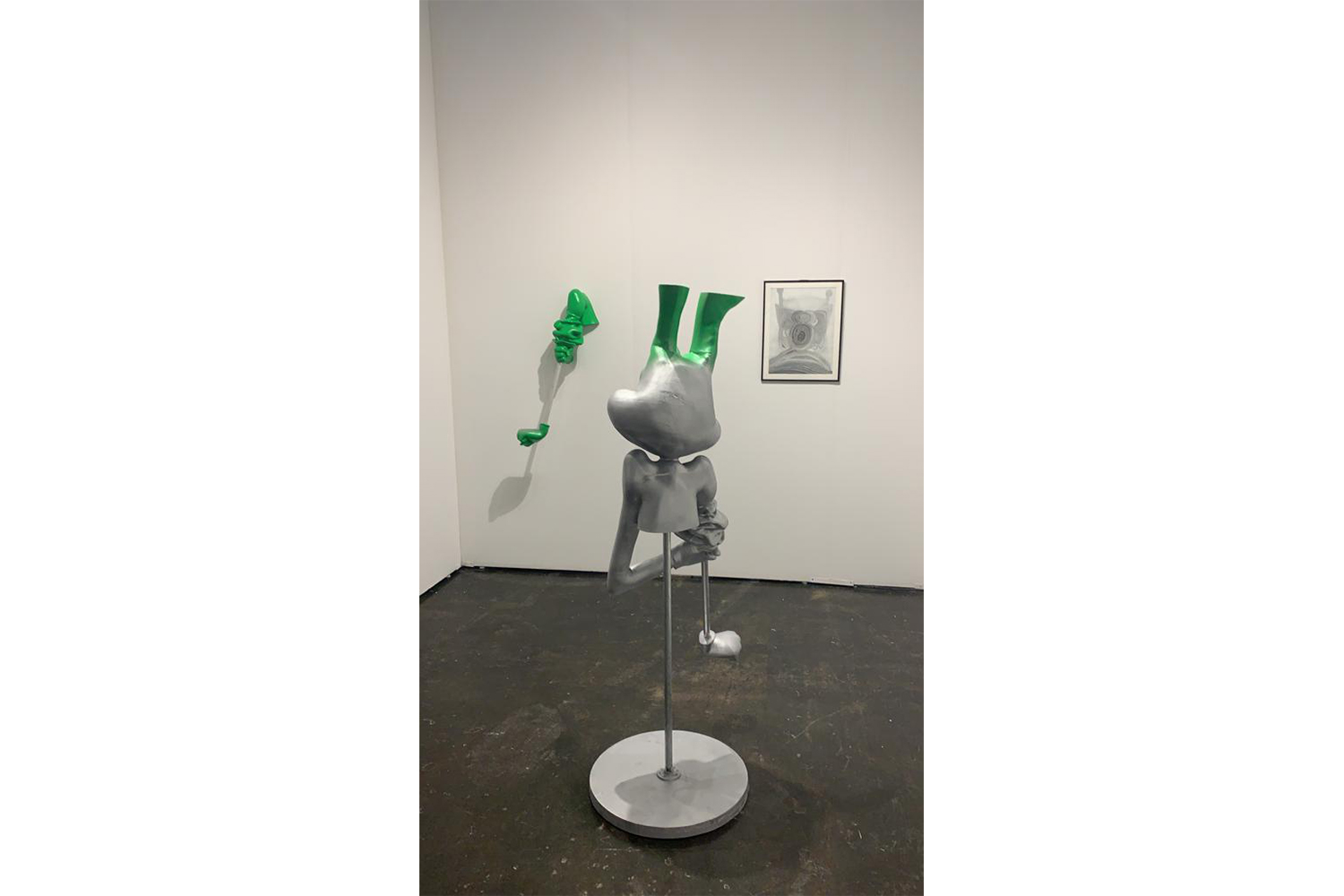

A short Uber ride away (during which the driver happily shared his vaccine microchip theories and his subsequent refusal to follow any government mandates — according to him it’s a slippery slope to communism masterminded by Dr. Anthony Fauci), the Rubell Museum greeted visitors with the final days of Narcissus Garden, Yayoi Kusama’s sprawling installation of seven hundred stainless steel balls (the piece is on view until December 12, 2021). Initially presented at the 1966 Venice Biennale, this iteration had a definite glow-up, upgraded from the original plastic spheres (which were available for individual purchase at the time) for cold, hard, shiny and decidedly deluxe stainless steel. The piece, which predates Jeff Koons’s Rabbit (1988) by twenty years, functions in much the same way: reflecting the viewers’ desire back upon themselves, albeit in a much more dispersed and scattered way. But then again, what is desire if not the refraction of one’s own gaze? Desire was very much at work throughout the museum, from the displays of much-coveted bodies of work by its various artists in residence (several of whom have henceforth experienced a meteoric rise in their respective markets due to this high-profile exposure) to the newest exhibition, a room dedicated to the work of Swedish-born, New York–based artist Cajsa von Zeipel. The artist’s larger-than-life humanoid figures are assembled from cast latex (the same kind used for mass-produced sex toys) enveloped in extravagantly cheap fun furs and adorned with a dizzying array of consumer objects and knick-knacks, most of them disposable trinkets found in the various tourist shops on Manhattan’s Canal Street (key chains, stuffed animals, cheap suitcases, etc.). With their faces contorted into grotesque grins and grimaces, they almost seem like ecstatic survivors, bunkering down to rave out the final days on a quickly unraveling timeline. The phrase “accelerationist rococo” also came to mind.

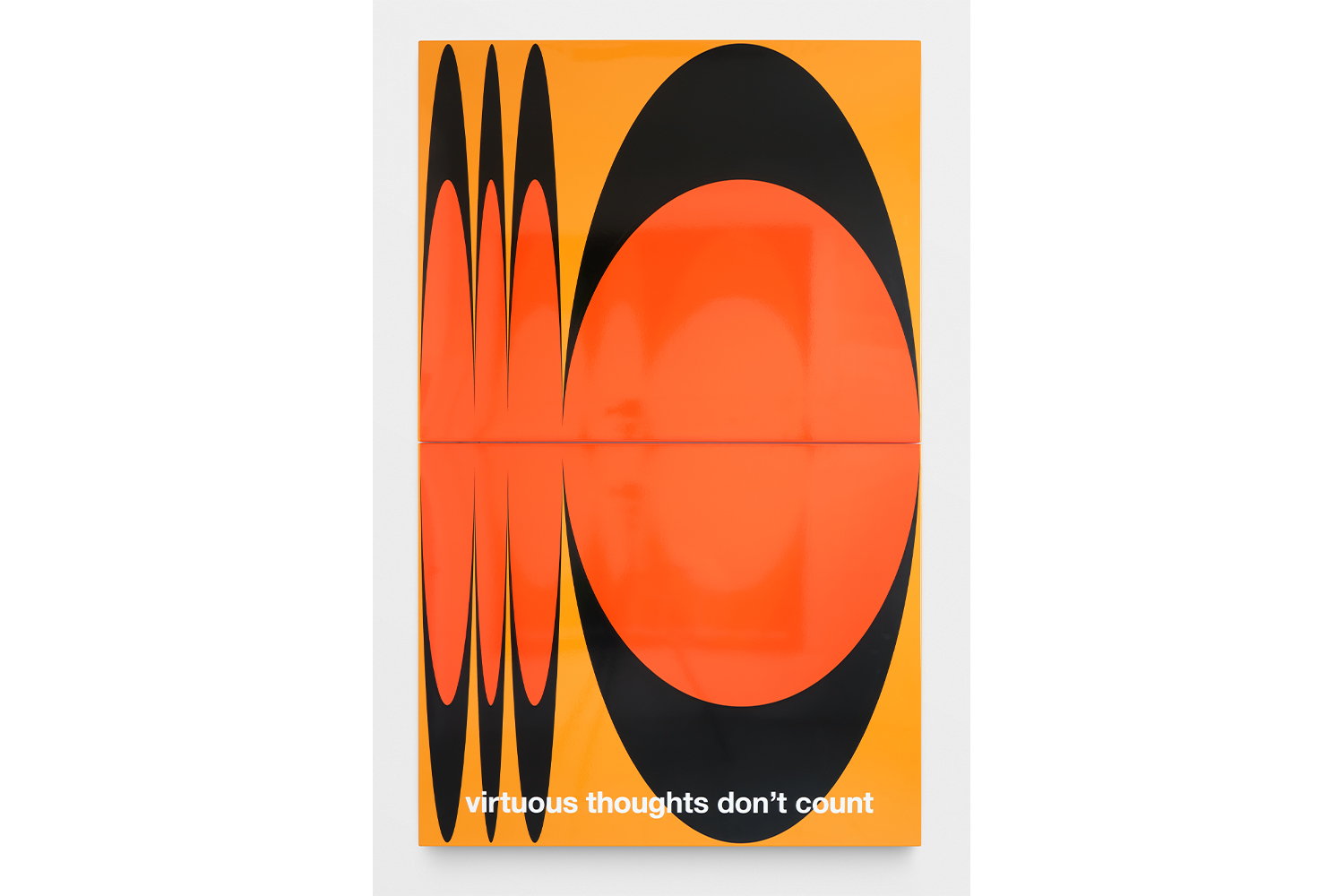

Nora Turato, virtuous thoughts don’t count, 2021. Vitreous enamel on steel, two elements.

192.5 x 120 x 3 cm.

Photography by GRAYSC. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich.

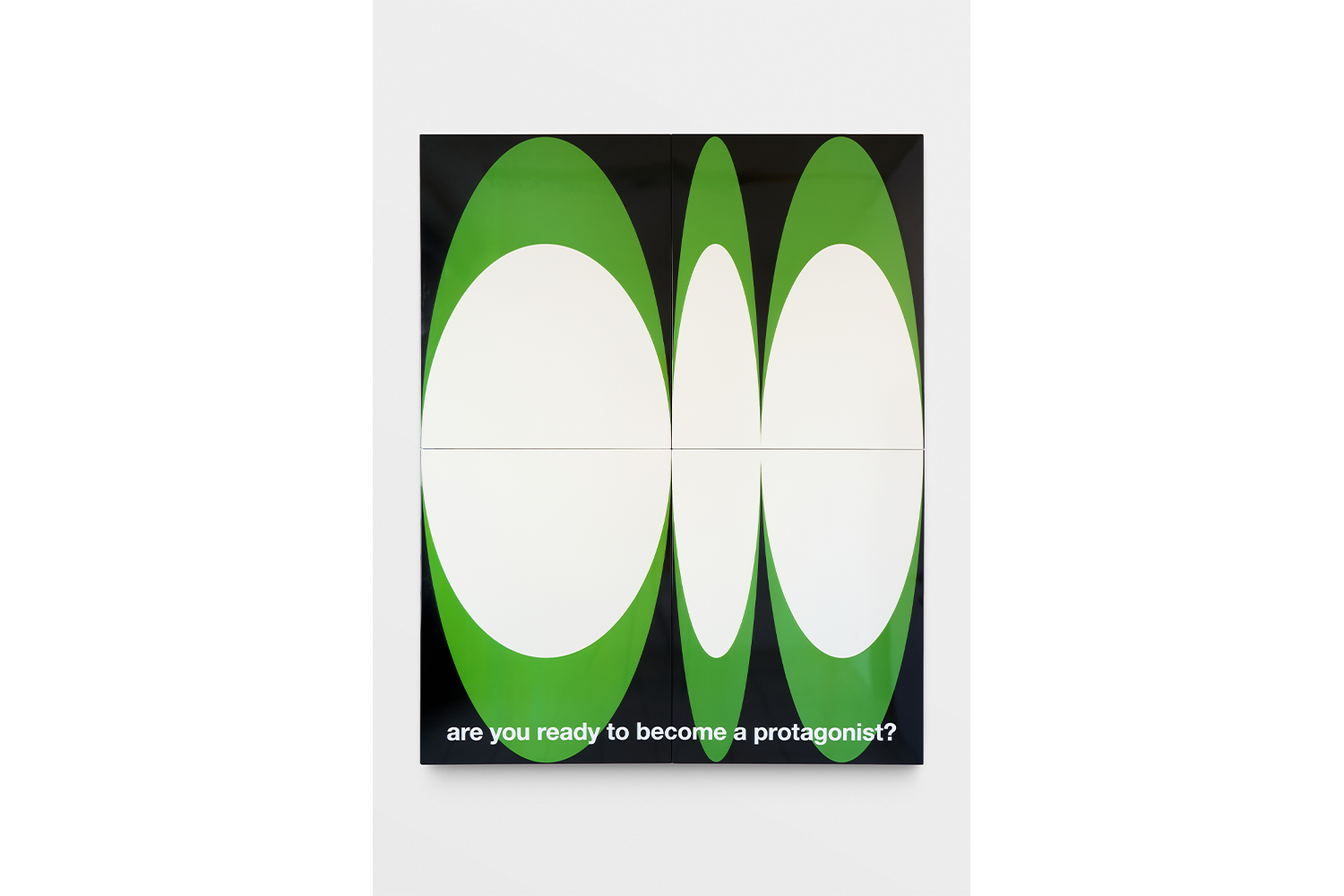

Nora Turato, are you ready to become a protagonist?, 2021. Vitreous enamel on steel, four elements.

242 x 192.5 x 3 cm. Photography by GRAYSC. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich.

Farah Al Qasimi, Still Life with Sample text and Pina Colades, 2021. Archival Inkjet Print. 101.6 x 76.2 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Helena Anrather Gallery, New York.

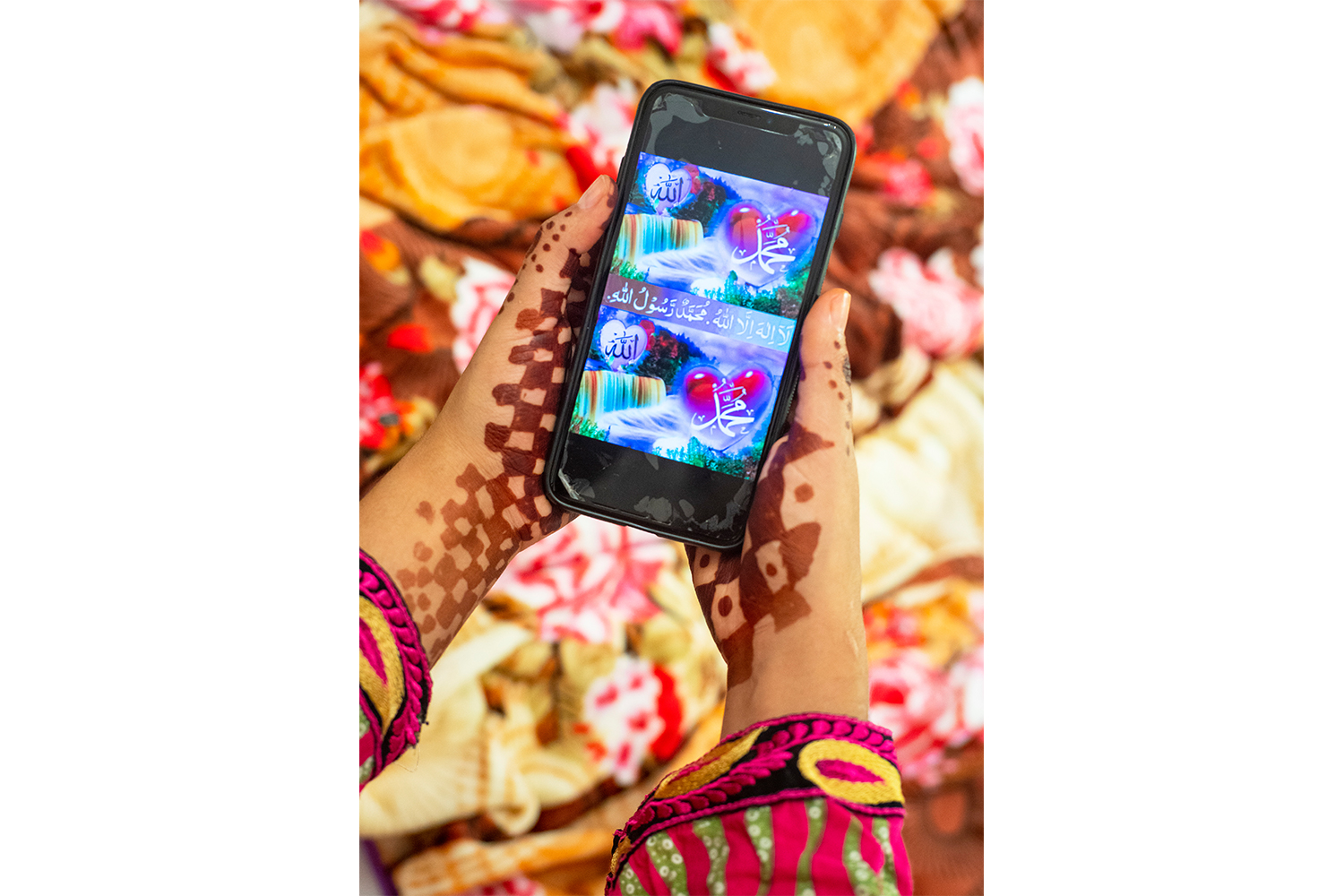

Farah Al Qasimi, WhatsApp Greeting, 2021. Archival Inkjet Print. 27.9 x 20.3 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Helena Anrather Gallery, New York.

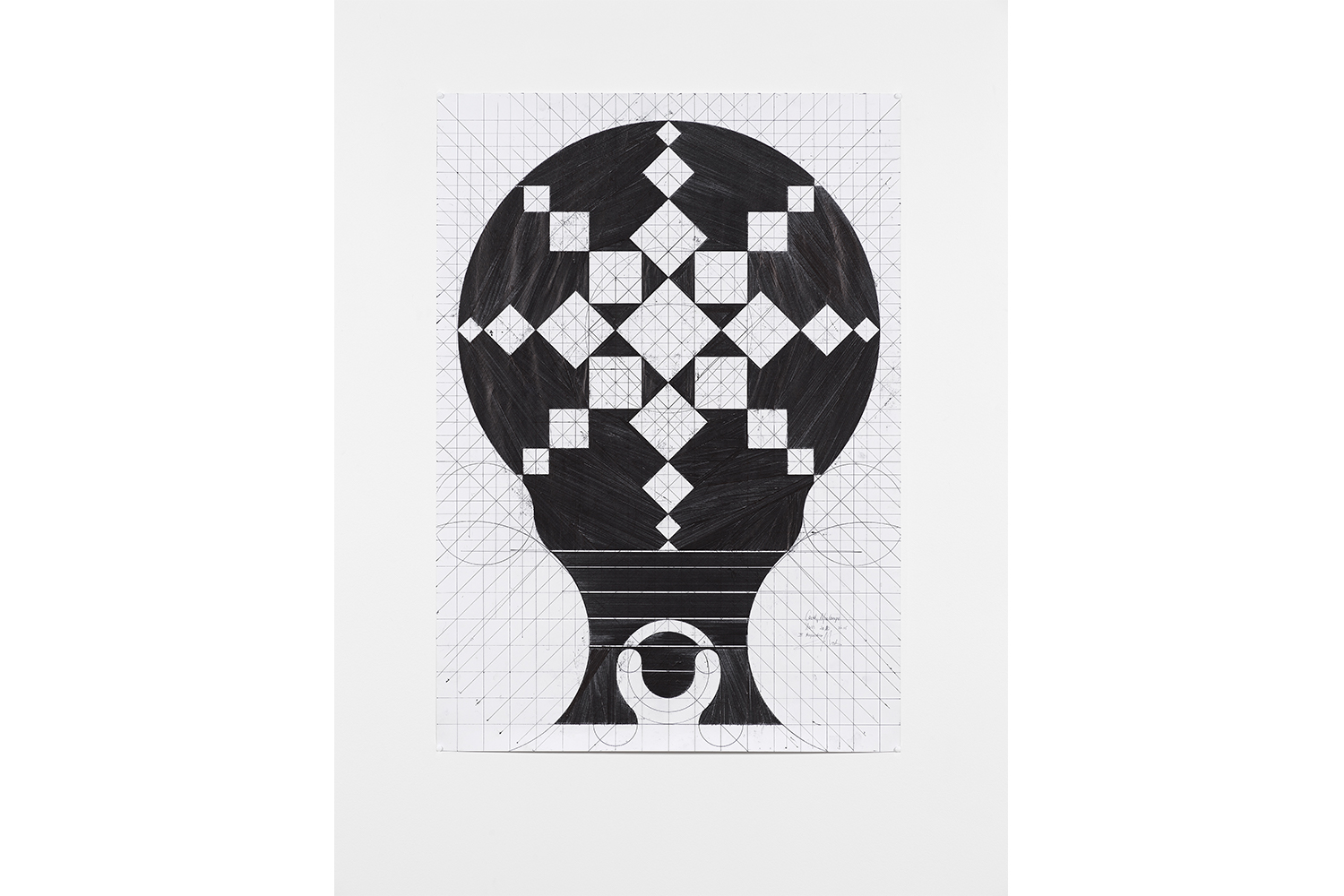

Jean Katambayi Mukendi, Covid 4 Afrolampe IV Perspective Mars 2020 2h05, 2020. Pen on paper. 100 x 70 cm. Photography by Dario Lasagni. Courtesy of the artist and Ramiken, New York.

Jean Katambayi Mukendi, Migration, 2015. Paper, cardboard, copper wire. 160 × 95 × 98 cm. Photography by Anthea Pokroy. Courtesy of the artist and Ramiken, New York.

Across a traffic-jammed causeway, the main event, Art Basel Miami Beach, was anchored by the usual collector trophies — many of them sold long before they touched down and were uncrated at the generously air-conditioned convention center. I was pleasantly surprised to see that despite the hegemony of painting (it is after all the easiest stand-in for value), there was a wide assortment of practices amply represented, especially within the typically “younger” sections of the fair, Nova and Positions. Highlights included Nora Turato’s enigmatic enamel panels at Galerie Gregor Staiger; Em Rooney’s poetic photo-based wall sculptures at Bodega; Farah Al Qasimi’s photo installation at Helena Anrather (which took home the City of Miami Beach Legacy Purchase prize); and Ramiken’s solo presentation of Congolese artist Jean Katambayi Mukendi, whose schematic drawings articulated around light bulb motifs and colorful architectural sculptures take an adept look at the long insidious burn of colonialism while refining a unique material lexicon that is explicitly his own. With Omicron easily falling into the colonial narrative (and the variant itself the byproduct of a radical vaccine disparity between countries), the work felt quietly poetic and incredibly important.

Yayoi Kusama, Narcissus Garden, 1966-. 700 stainless steel spheres. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the Rubell Museum, Miami.

Nschotschi Haslinger, Vibrationen IV, 2021. Glazed ceramics. 23 x 31 x 42 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Exile, Vienna.

Nazim Ünal Yilmaz, Untitled, 2021. Oil on canvas. 127 x 101.6 cm. Courtesy of the artis and Exile, Vienna.

Nazim Ünal Yilmaz, Untitled, 2021. Oil on canvas. 127 x 101.6 cm. Courtesy of the artis and Exile, Vienna.

Exile. View of the booth at NADA, Miami, 2021. Courtesy of Exile, Vienna.

Clima. View of the booth at NADA, Miami, 2021. Courtesy of Clima, Milan.

Clima. View of the booth at NADA, Miami, 2021. Courtesy of Clima, Milan.

Andrew Ross, fight loop sconce, 2021. Thermoplastic, epoxy coating, polyurethane, paint, aluminium, plywood. Photography by Daniel Terna. Courtesy of Clima, Milan.

Andrew Ross, fight loop, 2021. Thermoplastic, epoxy coating, polyurethane, paint, aluminium, stainless steel, plywood. Photography by Daniel Terna. Courtesy of Clima, Milan.

Back at the Ice Palace, this year’s iteration of NADA was noteworthy for how conservative it initially struck me. Usually seen as a bastion of emerging art and risk-taking young galleries, this year’s installment seemed to unfold as an endless array of colorful, vaguely figurative and somewhat interchangeable paintings. One can hardly blame young galleries, no doubt keenly conscious of overhead, for being risk averse at this particular juncture; and perhaps that captures the double bind of this moment: whether to strike out into the wilderness or to retrace one’s steps to paths already worn and familiar. Still, there were definitely flashes of innovation, among them Cameron Spratley’s unabashedly agro photo collages at Chicago’s M. LeBlanc, which capture the frenetic energy of the current political tumult without romanticizing it or distilling it into an easily digestible figure. In fact, these works seem custom made to be difficult to swallow. Kai Matsumiya presented Robert Sandler’s photo collages populated by clowns — a familiar absurdist trope that nevertheless felt deployed here in fresh ways. Also notable were Jeanine Neuberger’s dreamy, Kai Althoff-esque paintings at the booth of Milan-based gallery Clima, which were juxtaposed against Miami-based artist Andrew Ross’s aluminum sculptures of Bugs Bunny. The latter seemed to neatly encapsulate my overall mood. Bugs, the anxious jester, was here deconstructed to reveal a steely armature that will linger long after any unsettling LOLs