Has the pandemic helped us to understand that we share this world? The air, the aerosols, the bacteria, the viruses? If this does not illuminate the concept of the commons, then what does? The current exhibition at Bergen Kunsthall aspires to tackle a subject of global significance: our dependence on a commons that is so big we underestimate it: the ocean. Twenty-seven artists relate their work to this topic without resorting to straightforward didactics — even though it is important to see the show and realize that one needs to learn a few things.

It’s not the first such exhibition: the current edition of the Helsinki Biennial is titled “The Same Sea,” and for years the Vienna-based TBA21 foundation has been running an exhibition program intensively focused on aspects of the ocean. This exhibition, however, has a very specific approach, which becomes obvious when looking at the accompanying publication. It doesn’t mention a single work in the show, and is anything but a glossy coffee-table book. Instead, it is a hundred-page newspaper that compiles research and information about the ocean, in particular the North Sea off Bergen, put together by students and graduates of the Bergen School of Architecture (BAS). It examines the “long and oscillating legacy of relations with the sea” within the surrounding province of Vestland, and takes as a starting point the contrast between descriptions of the North Sea as either an extremely industrialized body of water (think of fishing, oil extraction, shipping) or against the background of an optimistically envisioned “blue economy.” If the latter sounds like a seaman’s yarn, it may be: companies are currently drawing up scenarios to exploit the potential of deeper levels of the oceans, all under conditions of sustainability, of course! So far this includes ideas such as extracting rare minerals from the deep sea, cultivating and harvesting algae as a source of food, and developing of new sources of energy. It does sound a bit too good to be true. With further sections on the process of scrapping drilling platforms, and the economic and cultural aspects of salmon farming, it is fair to say that this newspaper forms the analytical backbone to the exhibition.

The emotional context comes from the city of Bergen itself: for centuries, Norway’s second city has defined itself through its relationship with the sea. This history has left its traces, which the collective VUMA reflects on in guided walks around the city, accessible also by app. The collective aspires to create space for young people of color in the cultural, political, and media landscapes of Norway. Thus, issues like how slave trade profits contributed directly to the arts in seventeenth-century Bergen is a subject here. To use art as a tool to better understand and negotiate anew the current impact of ancient history and the symbolic visibility afforded to it is among its worthiest causes.

Another work dealing with visibility can be found in the beautiful Bergen Natural History Museum, home to an elaborate nineteenth-century natural history display (e.g., stuffed animals, whale bones, a mandrake). If you open the wrong drawer, you will find it full of bug traps from the museum’s display cases. It’s not a mistake, but an intervention by Andy Lock from the Bergen Art Academy, titled The Wrong Bodies (2020). And yes, roaches are underrepresented in this exhibition, but this quip addresses selection, what’s wrong and right, representable or not, and this not only in terms of the museum but in terms of cultural identity altogether.

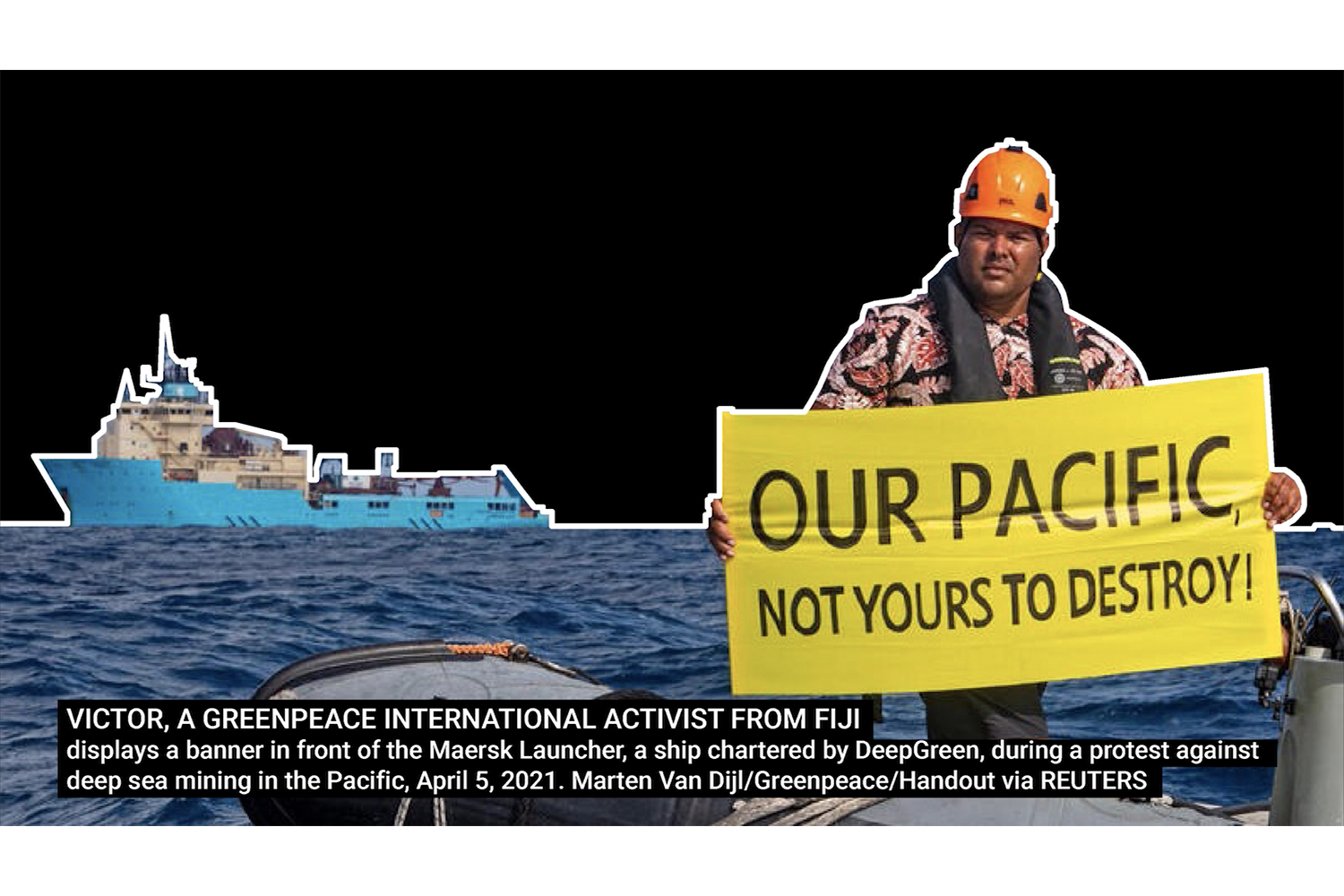

The dead roaches are not an official part of the Kunsthall exhibition, but a video by another collective, INTERPRT, is. This work visualizes models for deep-sea mining and posits the environmental risks of exploiting parts of the planet that are more difficult to reach than the moon, making them mankind’s last remaining frontiers. The ultimate frontier, however, may remain the question underlying the ocean: How can we live together?