It can be hard to organize one’s thoughts while trying to digest such a vast range of artworks across multiple fairs, institutions, and independent spaces. This return to Basel was electrifying but also alienating; perhaps I was not yet ready to return to the overly rich art diet that was placed on pause back in 2019.

The feeling of bulimia at seeing so much art again, in person and so quickly, was mercifully arrested in the presence of Marguerite Humeau’s Riddles (Jaws) (2017–21), a sound installation, if it can be called that, at the entrance of the exhibition “INFORMATION (Today)” at Kunsthalle Basel. The work encapsulates, at least for me, the sensibility and leitmotif of what the city offers on the occasion of the return of Art Basel.

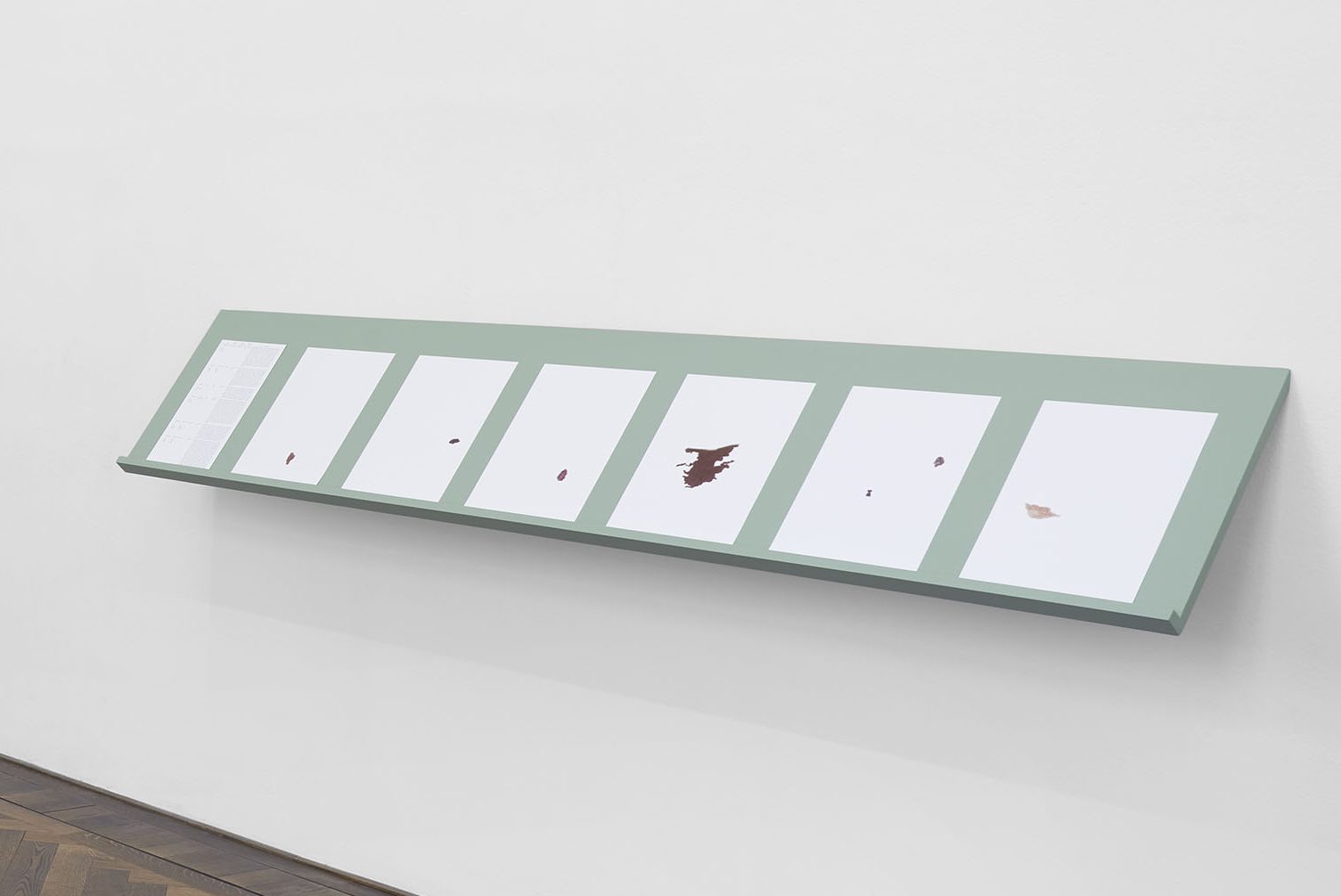

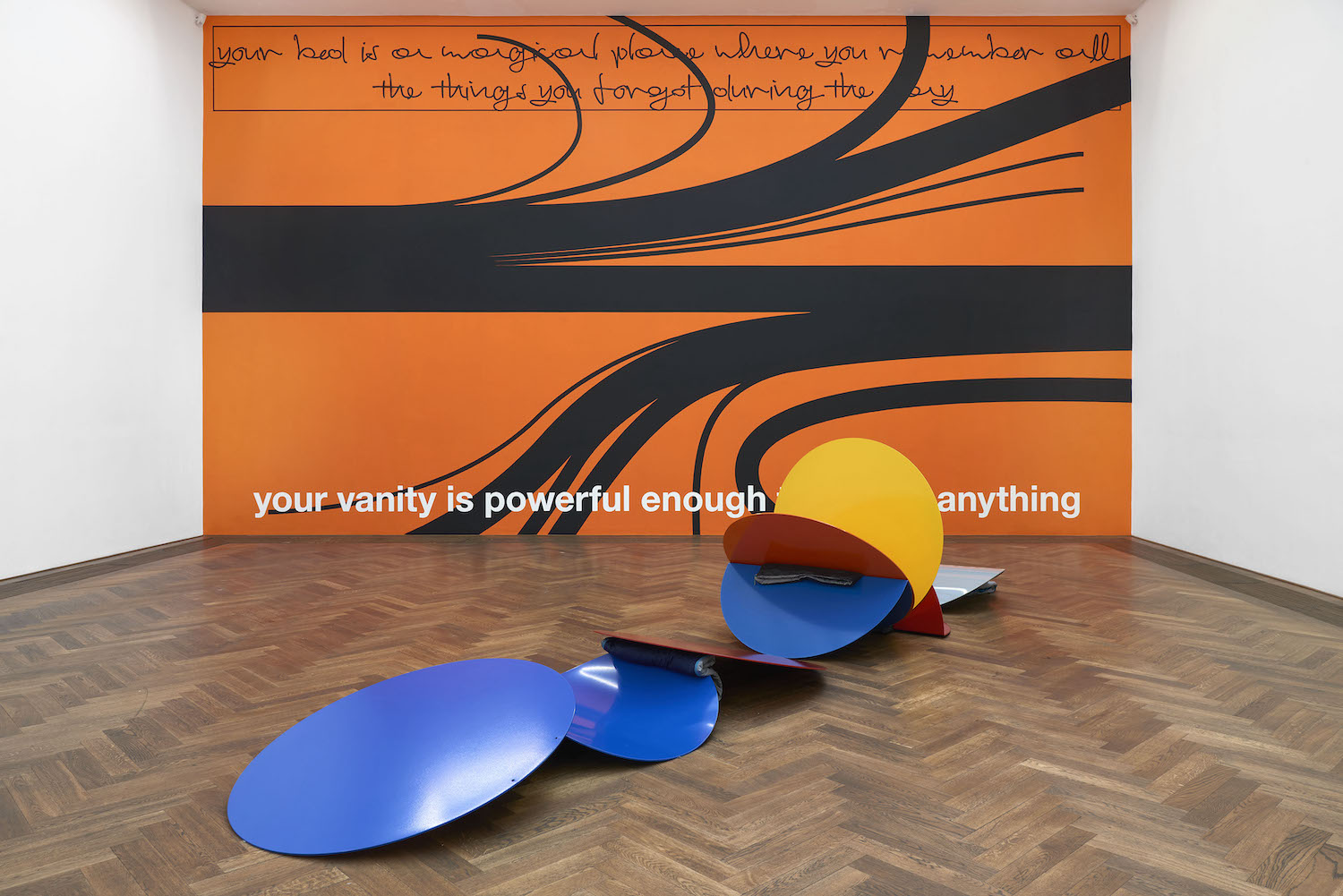

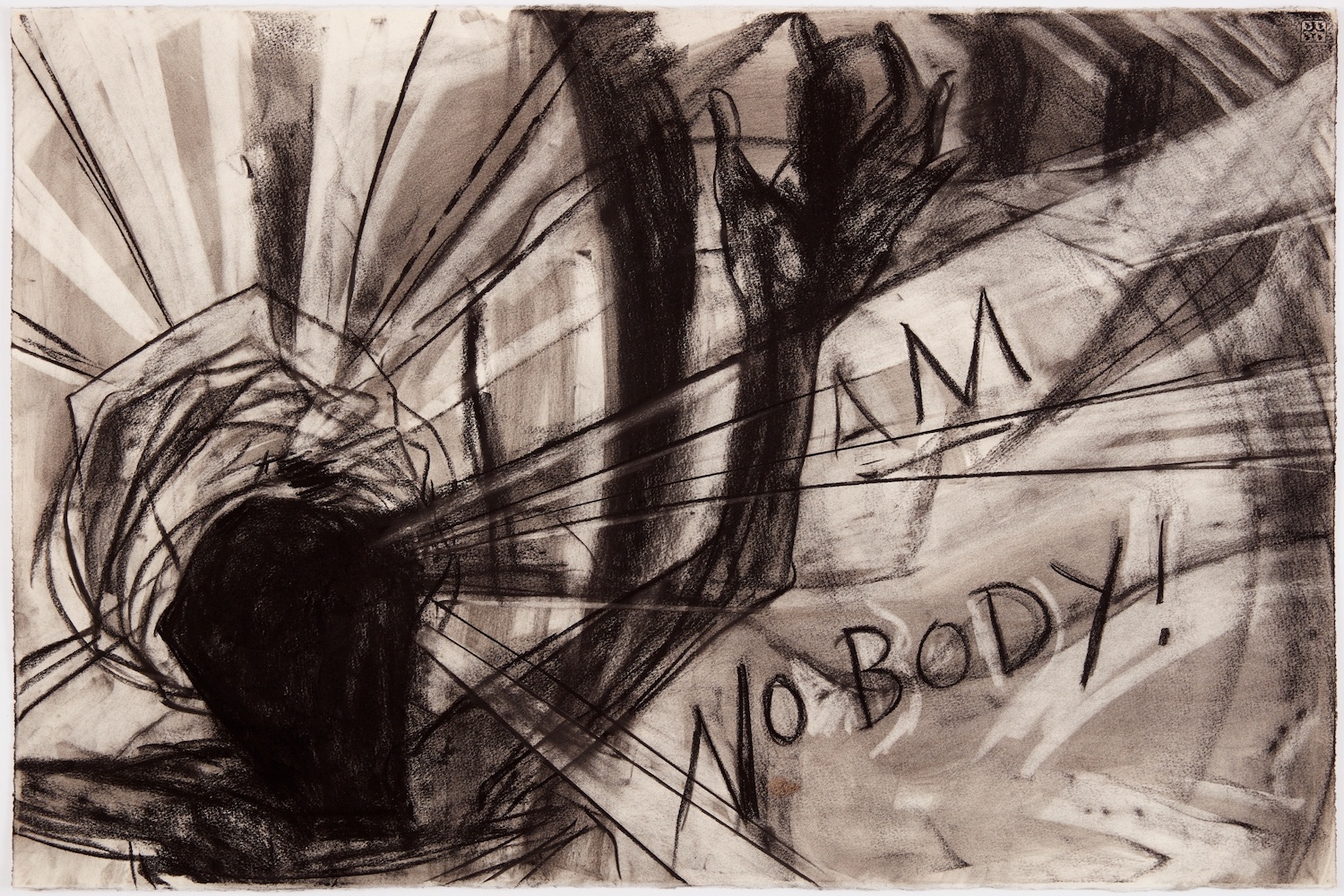

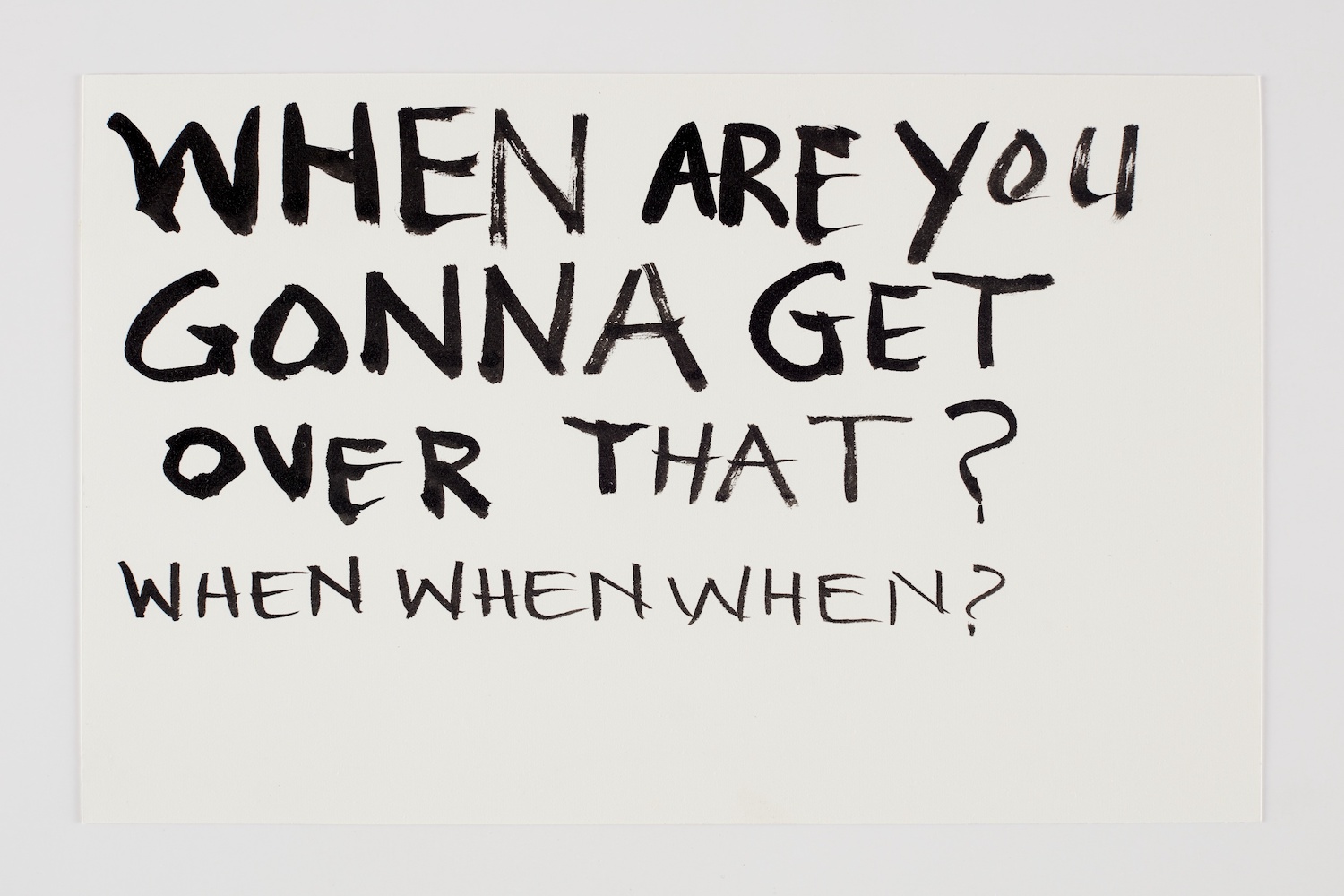

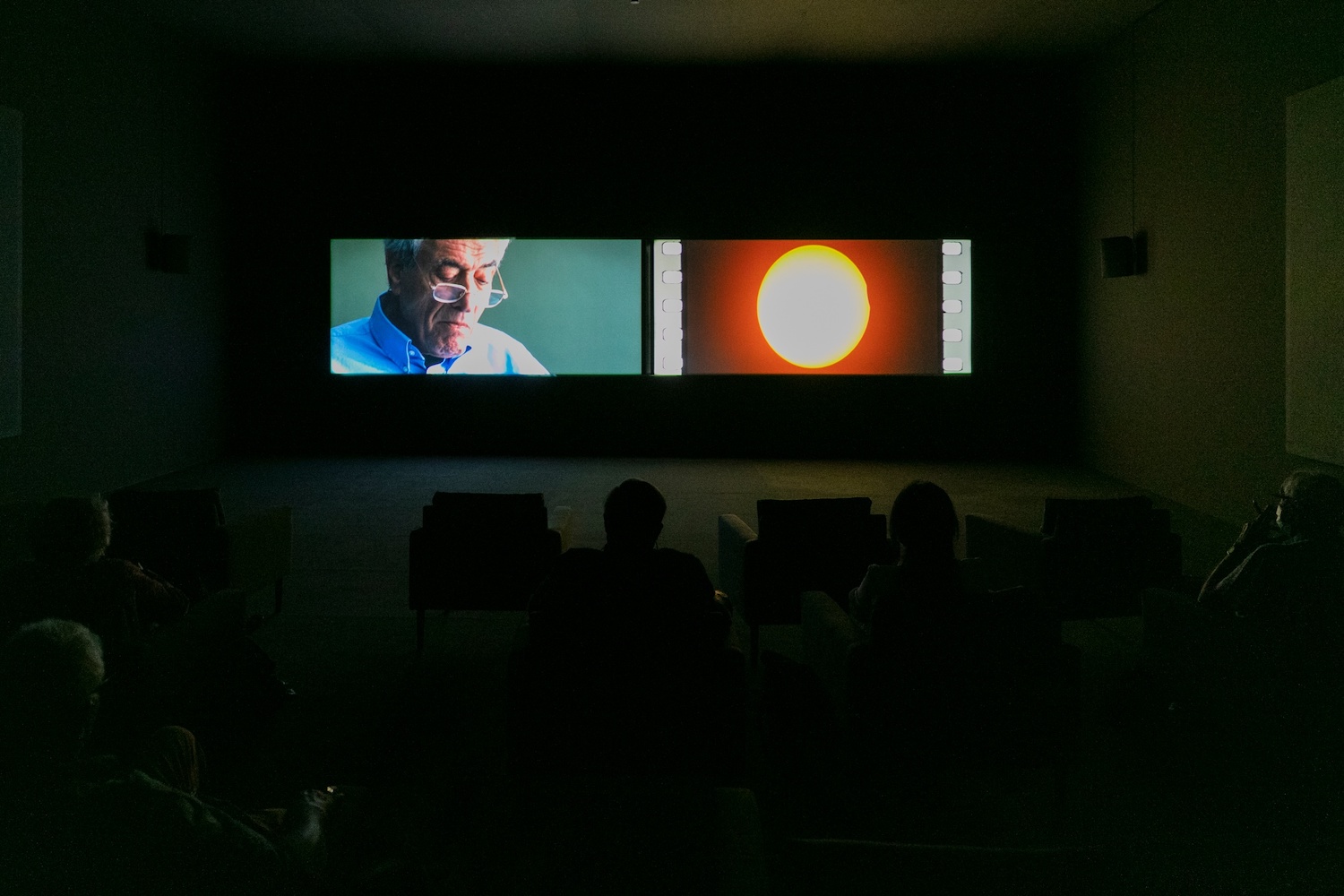

Muscular and in some ways sensual, Humeau’s installation is an obstacle, an invitation to slow down. A double row of hardened chrome barriers forces visitors to pass through the entrance of the exhibition — the time of one’s visit already determined — while accompanied by the annoying, intermittent sounds of the sculptural elements, which seem to communicate with each other, as well as with us. The work is part of Elena Filipovic’s response to the legacy of the famous “Information” show at MoMA, New York, in 1970, in which she has selected works by sixteen artists who reflect on the crisis of information today. Can we really say that Kynaston McShine’s exhibition was more “political”? It was, without doubt, one of the first international surveys of conceptual art, with more than seventy artists presenting political, processual works, many based on the participation of the public, challenging the exhibition space assigned to art, the museum, which was already going through a crisis that we might say, today, is irreversible. The 1970 exhibition confronted institutional hierarchies with a panorama of works that eluded typical museological classifications, transforming the way the institution presented art. The exhibition at the Kunsthalle is more measured but no less effective in its careful selection of work spanning a variety of mediums: Laura Owens’s paintings, which explore a zone somewhere between trompe l’oeil and digital pixels; Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s prints that testify to the possible evolution of the human body in the process of reincarnation; Ima-Abasi Okon’s structure supported from the ceiling with very thin wires and steel hooks, emphasizing the physical and bureaucratic architecture of information; and Sondra Perry’s multi-channel installation set against a backdrop of chroma-key blue, which interrogates the forced appropriation of black bodies as well as their cultural heritage. Perry recently won the biennial “Dream Commission” award sponsored by Muse, the Rolls-Royce Art Program, for which she will produce a new moving-image work. At the Fondation Beyeler she presented a preview of the work she will show there in February 2022: a multi-channel performance installation in which, while sitting on a sofa with the backrest resting on the floor, she talks to a woman through a tablet. The perspective is reversed, and, together with the dialogue, the work prompts a sensation of estrangement from reality, a parallel reality not so far removed from that of the ubiquitous remote communication platforms we now use to interact with each other.

Entering Perry’s world after passing through the “Natureculture” exhibition — a re-proposition of the Beyeler’s permanent collection featuring masterpieces of the European avant-garde and beyond — was enough to induce vertigo. I’ll mention just a few highlights: A 1940’s Paul Klee; Rousseau’s The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope(1998/1905); Barnett Newman’s Queen of the Night II (1967); the Rothkos. The theme of collection refurbishment animated one of the panels of Art Basel’s Conversations section, “The Museum of the Future,” in which directors of major global institutions tried to take stock of their future prospects. All seemed to agree that museums had had more time for research and to think about what to exhibit during the past year of pandemic and closure. A certain irony here was not lacking, as each touched on interesting points, though certainly not new to the latest debates on what a contemporary museum should be. Each talked about the importance of careful programming research, diversified collections, and the reality that public museums will be forced to “invent” their own future. “Long-term thinking means a contract with your government,” said Chris Dercon, who questioned the possibility of a future for museums that are private in nature.

The idea of the future — which fueled a considerable amount of literature in 2020 — also animated the panel “Rewriting the Future, Science Fiction and Contemporary” moderated by Mónica Bello with artists Sophia Al Maria and Rasheedah Phillips which considered the potential for science fiction to continue describing the future, and looked at the “dystopian in the everyday”; it also seems to be resuscitating the debate around how to support new artistic productions. The presentation of “Unfinished Camp,” the inaugural Unfinished initiative, at HEK House of Electronic Arts, also spoke of the future; the project’s creators, Hans Ulrich Obrist and András Szántó, called on artists to think about and participate in reimagining a more equitable and sustainable digital future. The artists who took part in the project, some of them very young, were motivated by the question: “What is the future of art in a decentralized world?” This led to dialogue but also conflict with the exhibition “Radical Gaming,” an investigation into artistic productions that incorporate the technologies and aesthetics used in video games, a clear example of how digital art is changing in form and language, and by extension its exhibition methods and relationship with the public.

I’ll jump back to Dercon, who also spoke of “digital sobriety”; the curious thing is that the return of Art Basel and Liste seemed to showcase a blender of languages and visual experiences much of it increasingly oriented toward time-based media productions. On the one hand, the city has privileged such work in collections and in public and private institutions, particularly in solo exhibitions like that of Tacita Dean and Kara Walker at the Kunstmuseum Basel; on the other hand, there was lots of painting and sculpture (with a notable presence of ceramics) at Messe Basel as well as Liste, and at the independent space Palazzina, where works by Maya Hottarek, Giorgia Garzilli, and Viola Leddi were of special note. Galleries at Liste probably took fewer risks in general, focusing mainly on painting and sculpture/installation. However, there were interesting developments: Ser Serpas presented by LC Queisser; Seventeen with works by Justin Fitzpatrick; two sculptures, a bronze cast and a jacquard canvas on aluminum by Margherita Raso at Fanta-MLN; Thomas Liu Le Lann’s asexual puppets at VIN VIN that call into question a certain kitsch aesthetic and the concept of gender; works by Cytter/Roebas and Jenna Bliss at Galerie Bernhard and Felix Gaudlitz; and Sydney Shen’s curious sculptures at Vacancy.

There was a very different atmosphere just a few dozen yards away at Messe Basel, perhaps fueled by the new face of a visual arts that insists on traditional mediums and constant reinvention. Here I think of a quote by Szántó that I read on Instagram a few days ago: “Even at Liste… it was hard to discern signs of what happened here. Yes, we saw more diversity. And maybe it takes longer for artists to truly digest current events… Call me a romantic but I wish I had seen more attempts by artists to sum up the precarious realities that envelop us in this difficult moment.”

Is it really fair to expect works to somehow make explicit the consequences of the last year and a half? It’s an open question, not an indictment of his expectations, shared by many others I’m sure. Perhaps what young contemporary artists have demonstrated is the possibility of a new world for art, one that is complex and full of references to the many different cultural, social, and geopolitical fabrics that are in rapid flux and requiring more and more space for diversity.

It is at Messeplatz that the most interesting things actually happen. During the week Monster Chetwynd activated his large-scale installation with a performance, TEARS (2021), created for Art Basel. Dancers in kaleidoscopic bodysuits, ready to go at any hour, danced on huge spiraling wooden benches and jumped in and out of giant transparent balls, colonizing the square and sometimes even the streetcar tracks. Chetwynd, inspired by Salvador Dali’s zorbs, imagines bodies as if they were drops that liquefy while dancing, a spark of joy that sinks into sadness, typical of our present. I left Basel after having participated in the performance of Cecilia Bengolea, who literally brought dancehall to the fountain of Messeplatz. If I had to imagine an art conceived for the public dimension today, it would be this: tourists and locals crossing Messeplatz, letting themselves be carried away by performers who share the movements of Jamaican dance, totally activating a space that produces manifold meanings, besides those with an undeniable impact on the art market.

In the air at Messeplatz there was a desire for the present. The future can wait.