All for the little nature of water lilies, Claude Monet developed a portion of land and diverted a narrow arm of the river Epte to quench his water garden. He acquired new hybrid lilies seen at the Paris world’s fair in 1889 and instituted a Japanese footbridge from which to admire them — the lilies themselves planted in thirty-liter pots to preserve their color balance.1

Bamboos, gingko and maple trees, Japanese peonies, wisteria and weeping willows: Monet’s artificial garden precipitated a mille-feuille of yet more artifice. It is an entropic dream-machine fashioned from imperial strategies of acquisitive transposition, commodifying Japanese culture and practice while simultaneously instilling its inferiority. Its extractive relations transform an ecosystem into a vignette manicured for the imaginary, beckoning the practice of circulation and representation. And yet, Monet once remarked: “I just took a catalogue and chose at random, that’s all.”2

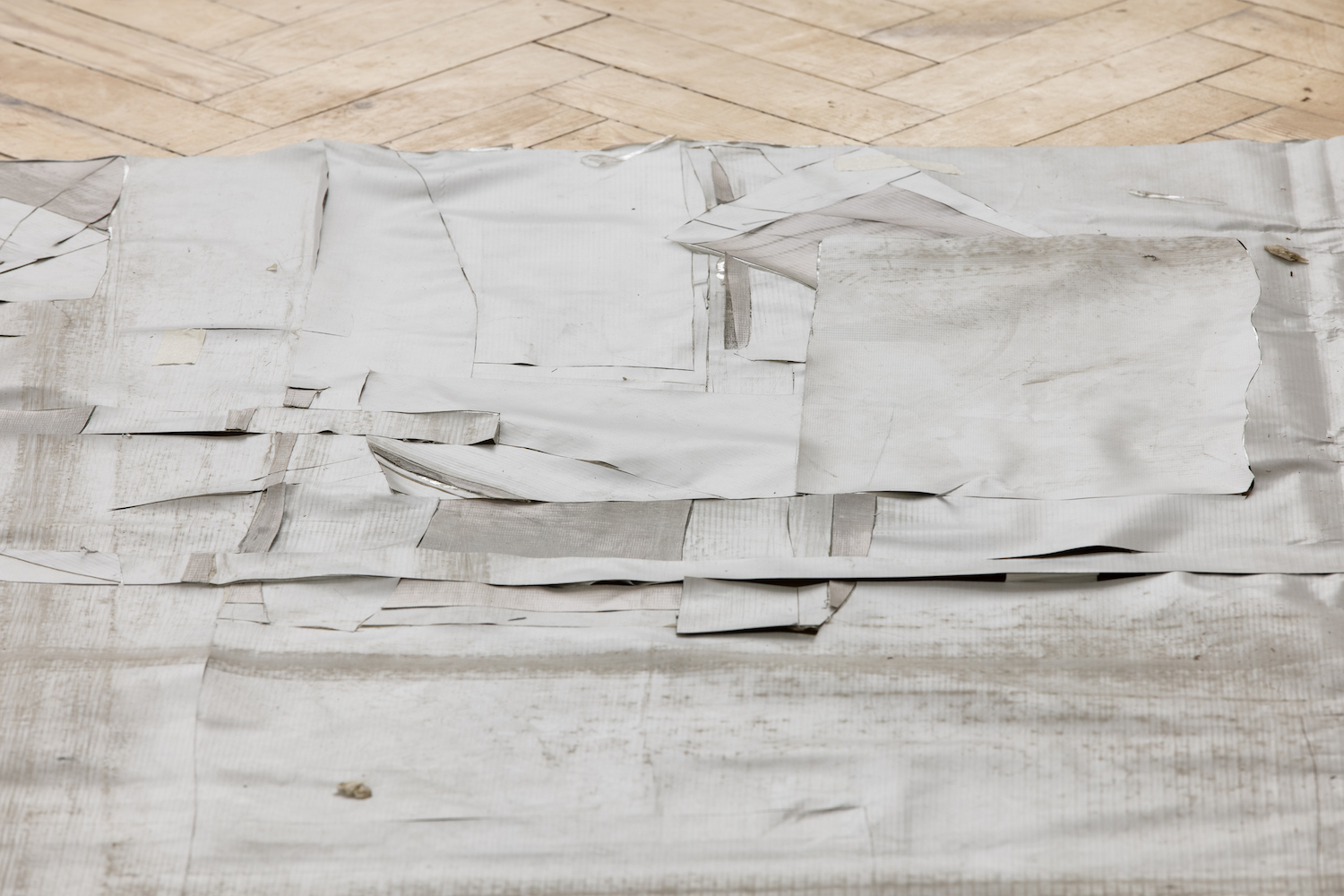

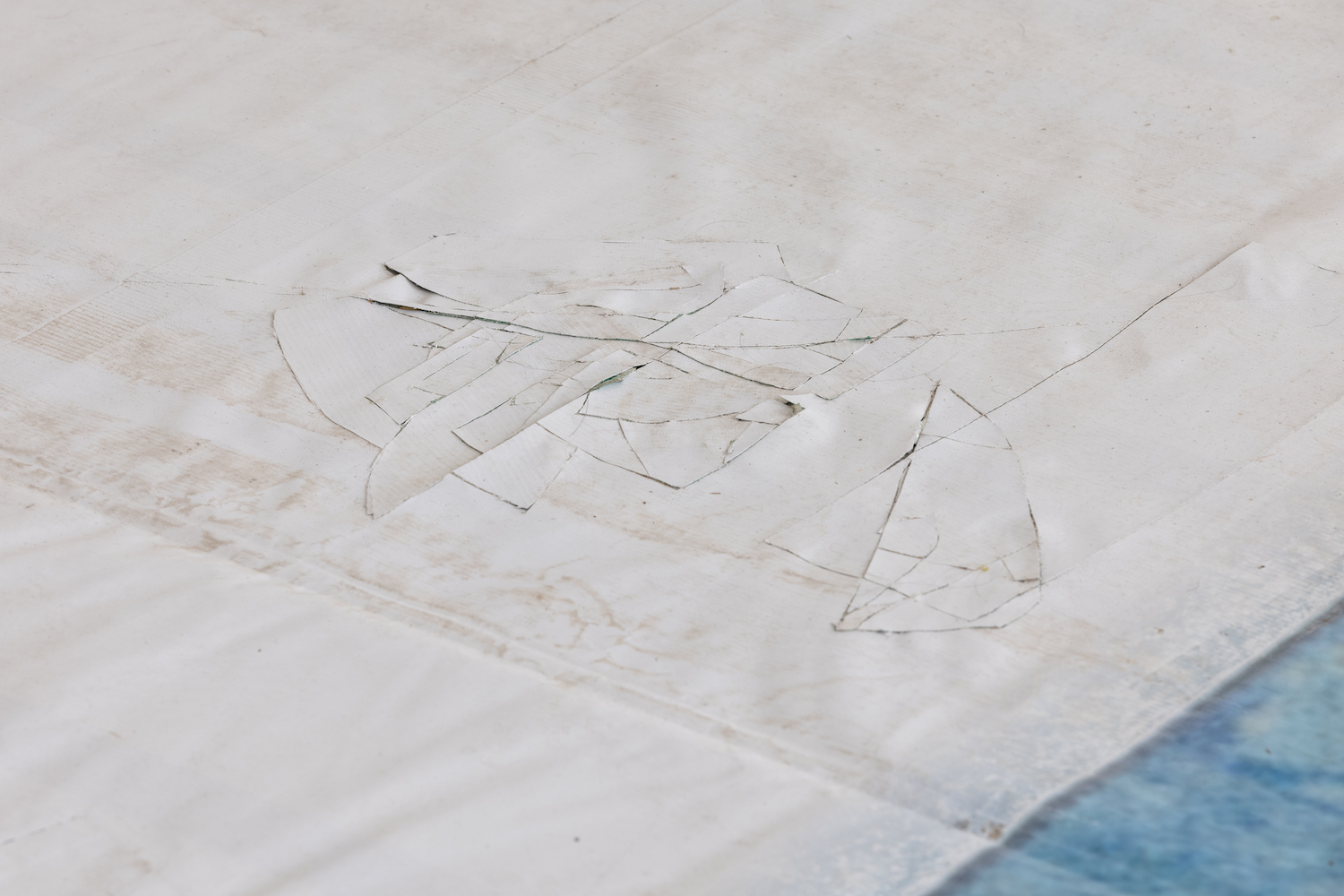

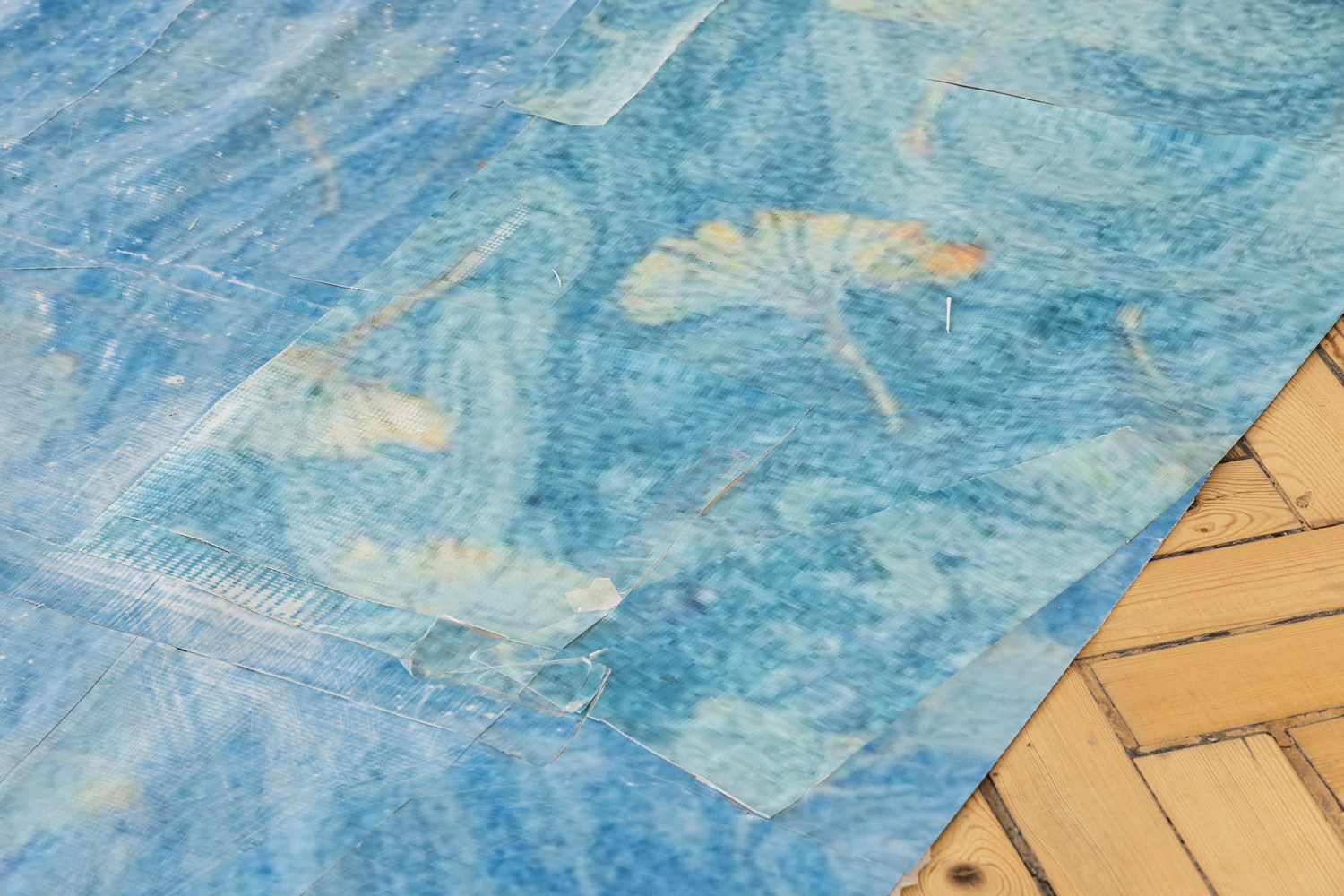

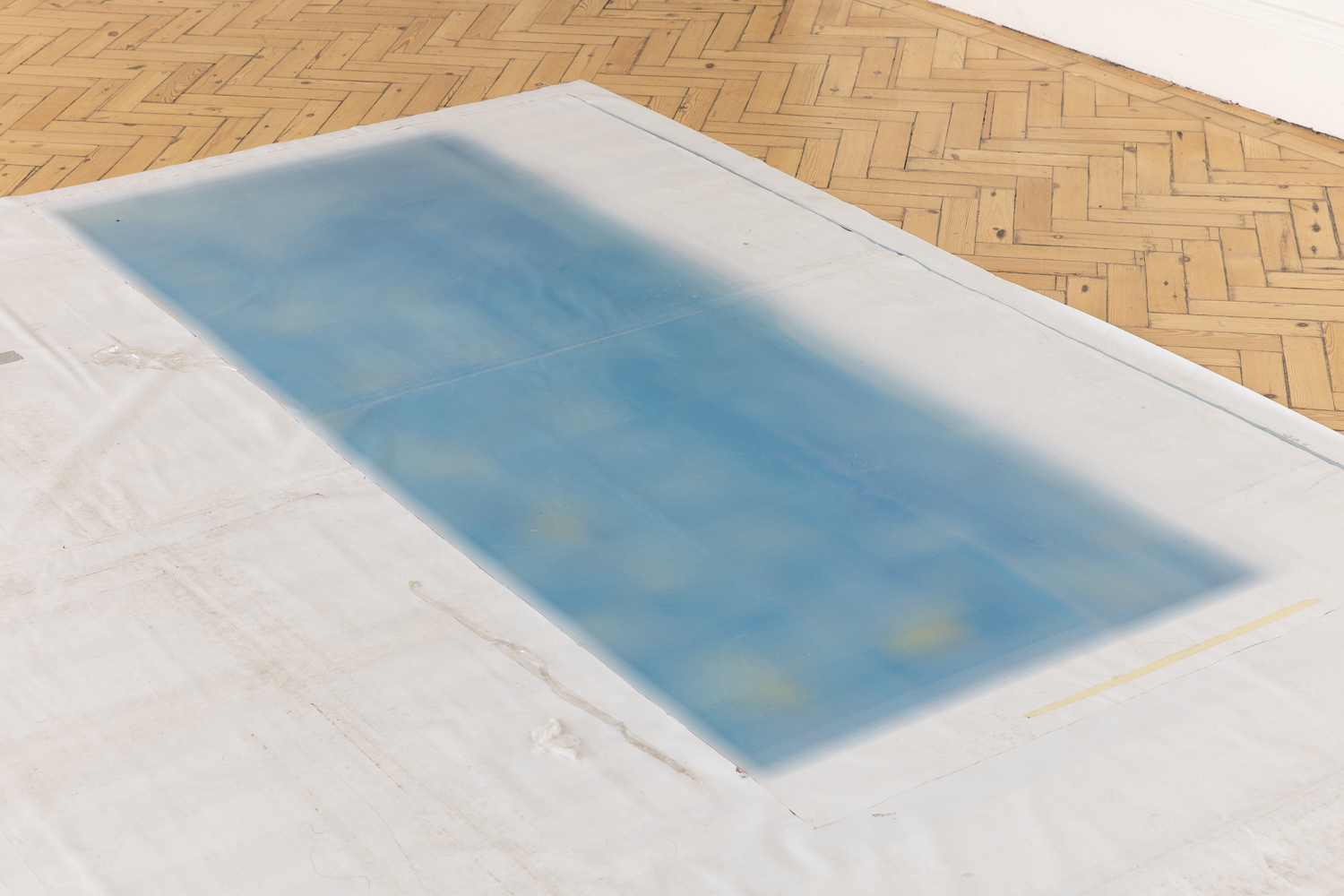

One reads Olga Balema’s exhibition title with a similarly insouciant tonality: Computer (2021), that’s all. The allusion of a kind of casualness is extended in the work’s source as well as the fact of its fatigued, worked state, while Balema’s sculpture involves the circulation and machinations of image production, it alights from an object literally domesticated underfoot –– a rug. Prostrate and parched, the rinsed, impressionistic blue swirls and shivery, etiolated gingko leaves in Balema’s large floor sculpture momentarily evoke Monet’s projective fantasies, yet within a field of deliberate, withering flatness. The pattern is sourced from a domestic “Prismatic Daydream Rug” and is digitally printed in the provisional materiality prevalent to billboards, each rug reproduced with varying degrees of lucidity and blur. Dog-eared, its blanched edges of pixilation disintegrate into blemished papery plastic, itself dragged through New York streets to accumulate dust, hair, dirt, as well as fresh afflictions: grazes, scuffs, peelings. Cut, stuck, stripped and compressed, Computer, then, is a plush attrition.

An initial encounter could ascribe the work with decrescence and deprivation, given its thinning materiality and atrophying imagery. This elected reducibility has created material exhaustion, which strains the desire to compel significance within something so open, passive, weak. Yet as a terrain of vulnerability, like staring into a pool of water that just reflects irresolute pondering, the tension of Computer’s disturbance and susceptibility is decidedly mutual: viewers are encouraged to walk over its surface and in turn forced to reconsider the influence of one’s step. Like a reverie: the slow lurch of dislocation. Yet there is no submergence or succulence; Computer perpetually deflates the daydream, letting its flimsy fantasy settle into the craquelure of its waterless surface. Balema’s Computer permits its own ruination in the destructive accretion of other physical gestures, splintering its integrity, or rather, its integrity hinging on doubt and defeat such that its meaning might extinguish into a litter of shagged pixels and crushed glitches. In spite of my desire for more pointed infestation and less causality, in its material data, Balema’s Computer is still, like every other computer, a time machine of sorts. Though in its entropic accrual of prosaic and contingent ‘data’, Computer’s memory is literally laid bare and in its devastation, more like the process of decay –– which ungrounds the ground.