“Hartung 80” is the third exhibition that Perrotin has devoted to Hans Hartung — following those held in New York and Shanghai — since it began representing the artist’s estate in 2017. It is also the most original of the three shows, with remarkable style and a depth of content that is almost museum-like in its scope. The show focuses on the painter’s output during the last decade of his life — he was born in Leipzig in 1904, and settled in the mid-1930s in France, where he died at the age of eighty-five. Perrotin’s two venues in the Marais, in Paris, reveal a narrative in three movements. The exhibition traces a reversed timeframe, with a beginning — and thus an end for the artist — set in 1989, the date of his death. This beginning is marked by acrylic-on-canvas works in graphic black and white, at once sober and very present in their vigorous gestural character, providing a sensitive visual preparation for the visitor’s subsequent introduction to a suite of works hallmarked by the performance Hartung Study, performed by Abraham Poincheval. The French artist Poincheval confined himself in a sitting position for seven days, from June 11 to 18, in a metal structure that pointed his gaze at the Hartung work T1989-A40 (1989), which he saw for the first time when he entered the structure. This novel act, accompanied by a system for controlling cerebral activity, thus makes this painting the longest continuously looked at work of art.

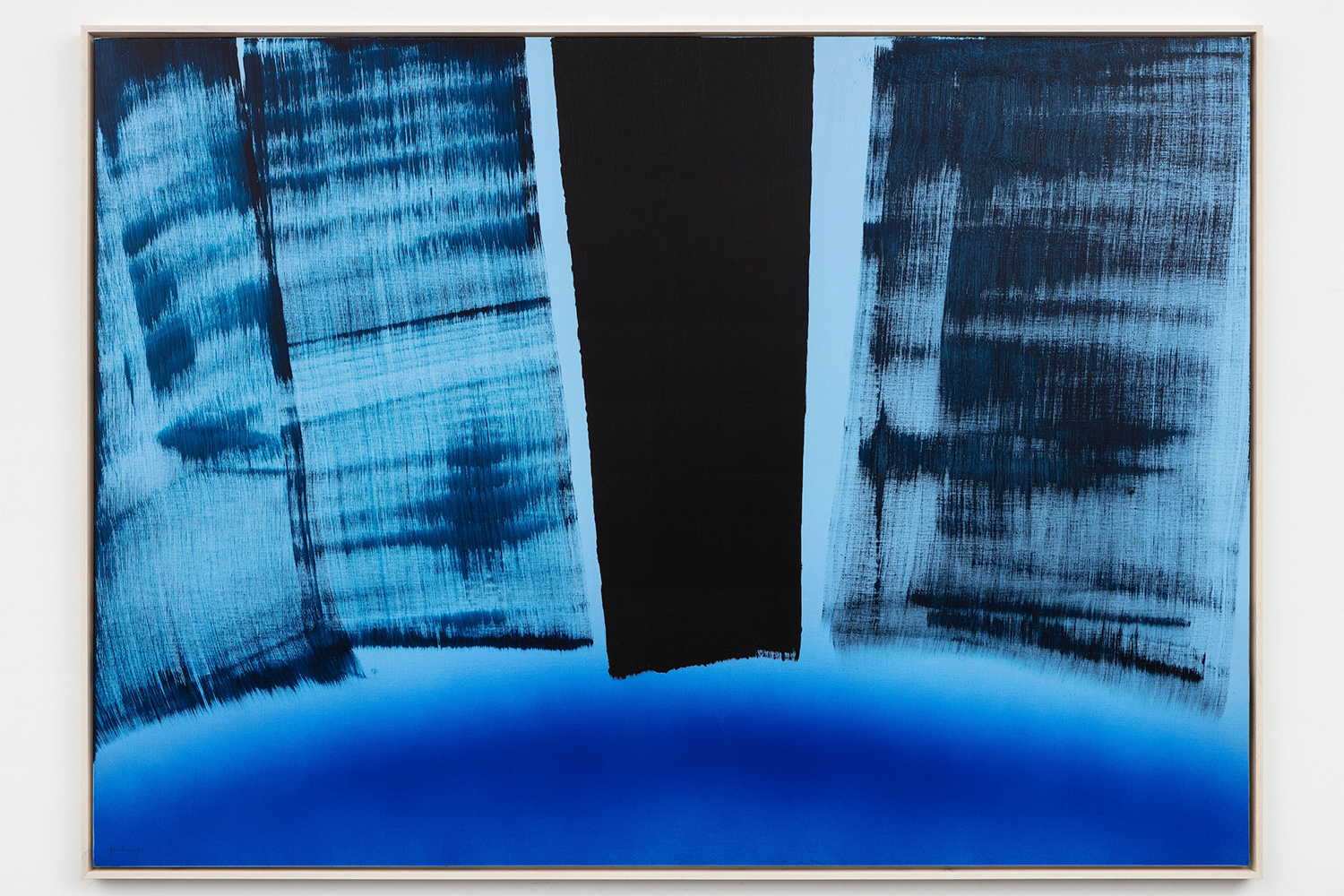

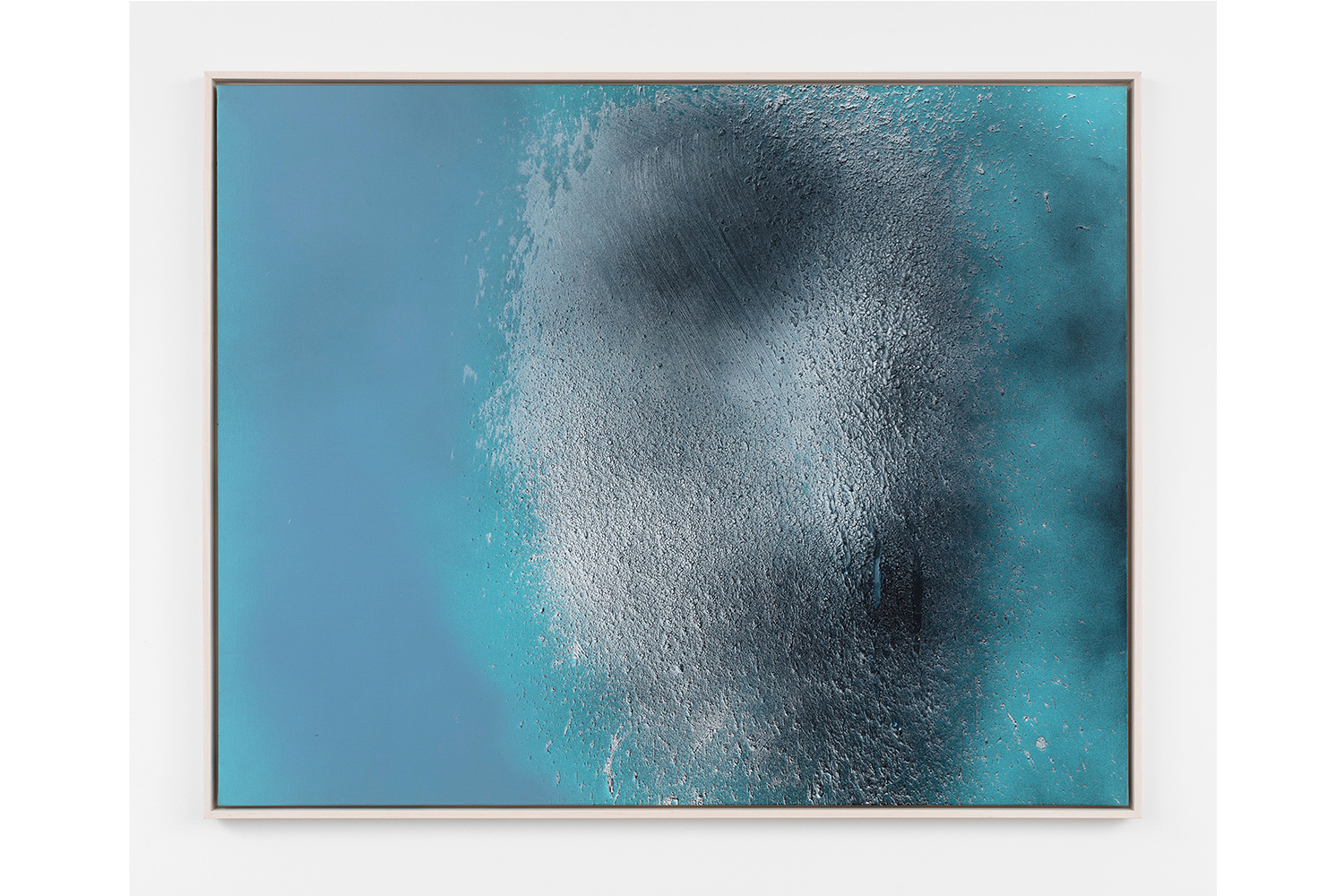

Flanking this huge metal armature are five canvases that convey Hartung’s embrace of color. Quite unlike his early days, marked by a dull prism of browns and grays, in the 1960s the artist embarked upon experiments with intense hues that he applied to the canvas in different textures and depths. Variations of reds, blues, and greens would be applied by a garden sprayer or an automotive spray gun, or else worked with brushes, fingers, or even a stiff broom made from the bushy shrubs that thrived on his property. After acquiring French citizenship at the end of World War II, Hartung and his wife, Anna-Eva Bergman, set up home in Antibes. There they acquired an olive grove, where they built a villa and their respective studios, today the setting for the Hartung-Bergman Foundation, where all the colors used by the artist are now kept: wielding an extremely diverse palette, Hartung, who was a particularly skilled when it came to experimentation, handled paints, produced mixtures, and made use of Tyrolean procedures that lent his paintings a granular, uneven density with an almost sculptural quality.

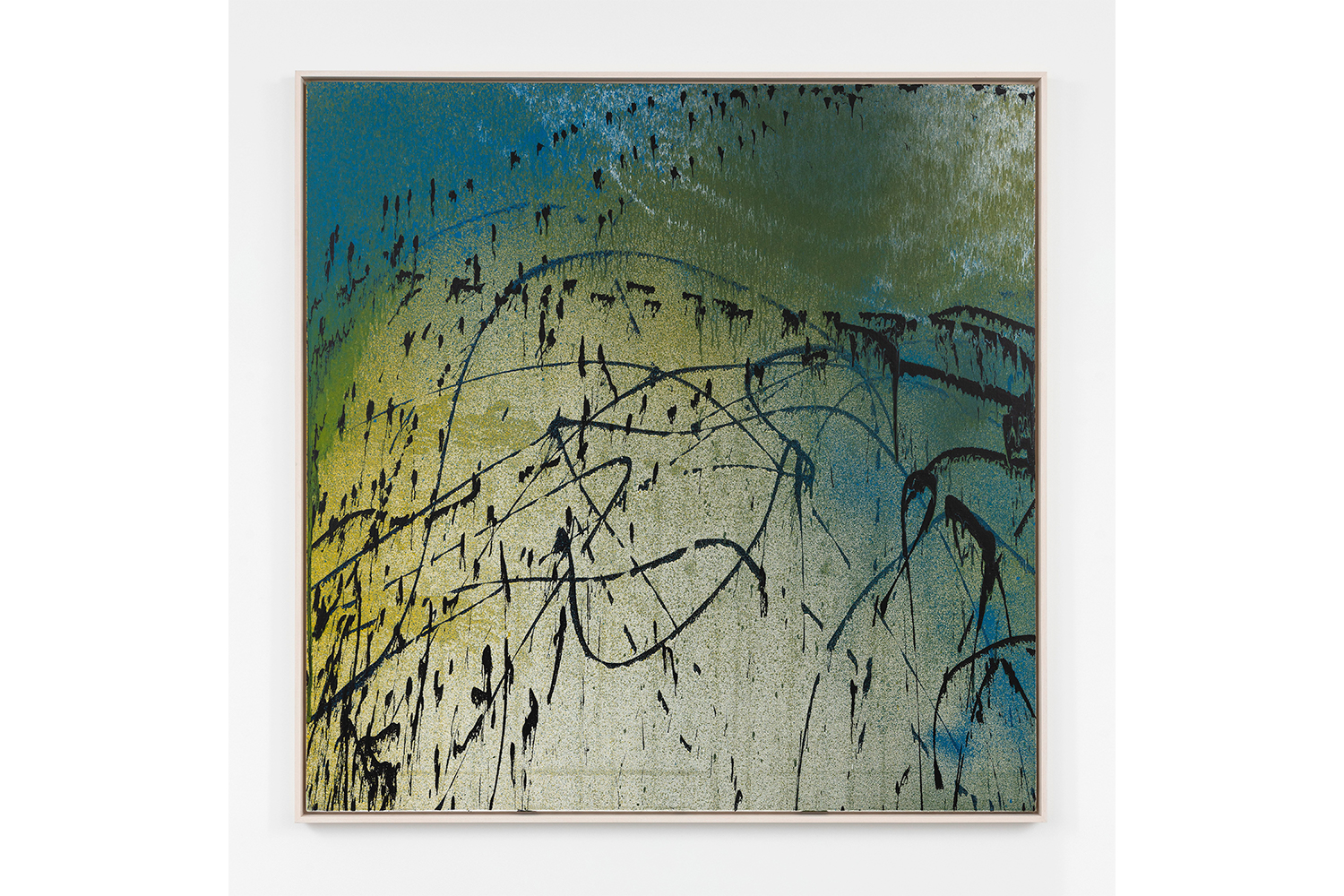

Hartung’s life was all painting, often executed to the sound of music, which rang out from his studio. A composition might be in dialogue with the music of Bach or Vivaldi, developing a form of choreography in space, a kind of motionless physicality that suggested the movements of a dancer. Hartung used a range of techniques, often with the help of industrial tools that enabled him to play with flat tints, sometimes striking surfaces with branches to create graphic traces while also making the most of the effects of dripping paint.

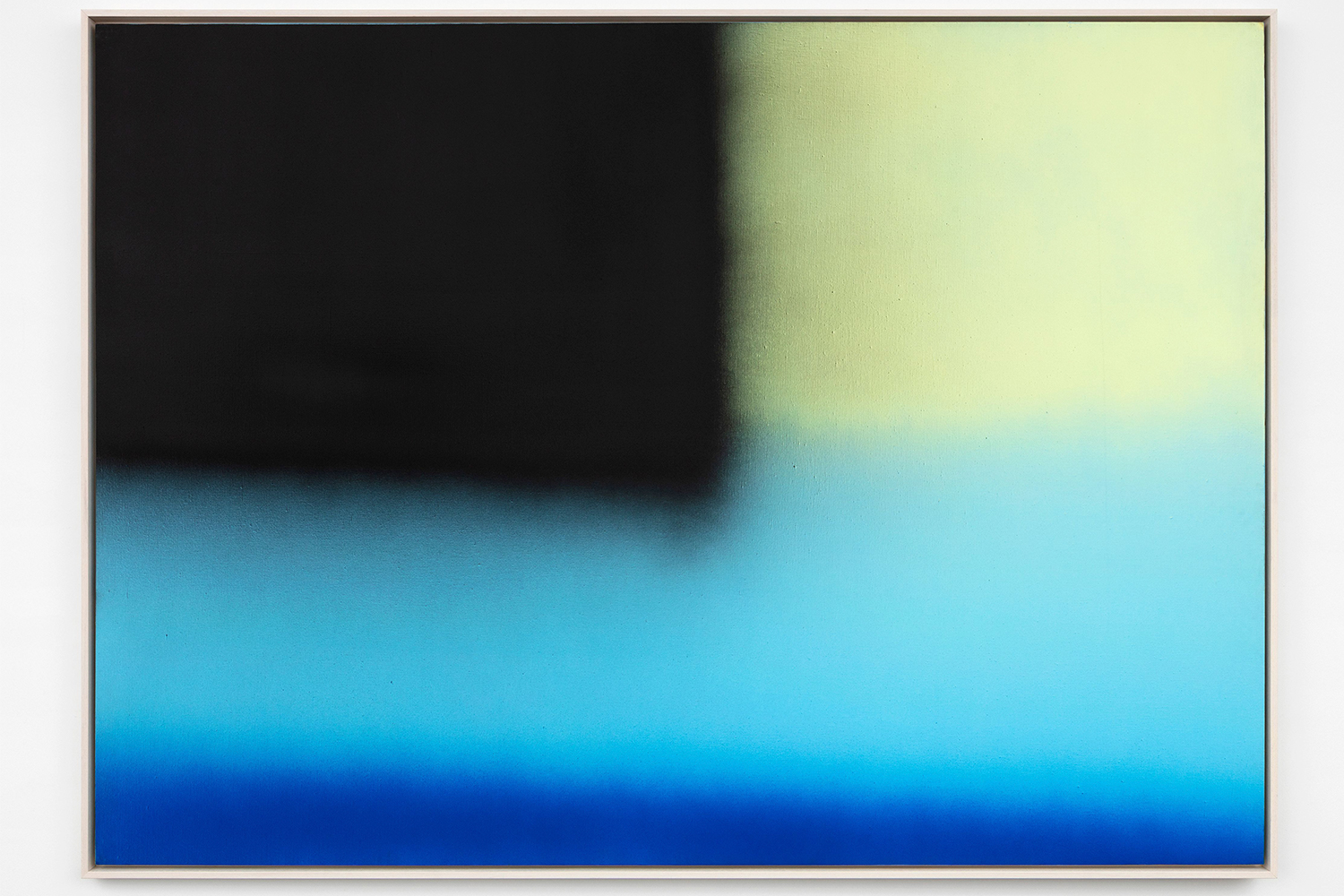

Underwritten by a gestural freedom, a spontaneity, and at the same time a mastery, Hartung’s works are meditative landscapes. So it is with T1989-A40(1982), in which the viewer is confronted by a quartet of colors with hazy borderlines, where geographies and atmospheres are traced across appealing textures. This large canvas is given a gallery all to itself. It is a hypnotizing work that seems to provide a bridge to the exhibition’s third section at the gallery’s second venue, on the Impasse Saint-Claude, which explores the relationship between Hans Hartung and Mark Rothko (1903–1970). “The link between the two artists has been very little, if at all, commented upon in art history. For a simple reason: Hartung gets the date of their first meeting wrong, putting it in 1947, but the fact remains that Rothko did not travel in Europe that particular year,” as Thomas Schlesser, Director of Hartung-Bergman Foundation and curator of the show, emphatically tells us.

In reality, the American went to Hartung’s studio, then located in Arcueil, in the Paris region, in April 1950. At that particular time Hartung was exhibiting regularly in the United States. Rothko told the artist, with whom he would have a long and friendly relationship, that his canvases were thoroughly viable with just large expanses of colors, without any graphic elements. Hartung would apply that lesson much later on, in 1983. Here, his works are accompanied by an exceptional loan from the Musée national d’art moderne – Centre Pompidou of Rothko’s No. 14 (Browns over Dark) (1963). This work, one of just two canvases by the American artist held in French public collections, helps to shed light on the parallels between the two artists, as well as Hartung’s freedom of spirit and action.

In all some fifty works — to which must be added archives, photographs, and a specially made documentary film by Thomas Schlesser — make this exhibition a significant milestone in the rediscovery of this essential twentieth-century artist, for whom many contemporary artists have expressed their admiration, including Christopher Wool and Katharina Grosse. His works produced in the 1980s are in fact the opposite of what we might think typical of the end of a painter’s career, especially a painter who was physically diminished — he lost a leg during the war — and affected by the death of his wife, Anna-Eva Bergman, who was his accomplice for (almost) a whole lifetime. That decade was the most unexpected, extraordinary, and avant-garde period. Yet it was also among the most prolific: in 1989, the year of his death, Hartung produced more than 350 works.

(Translated from French by Simon Pleasance)