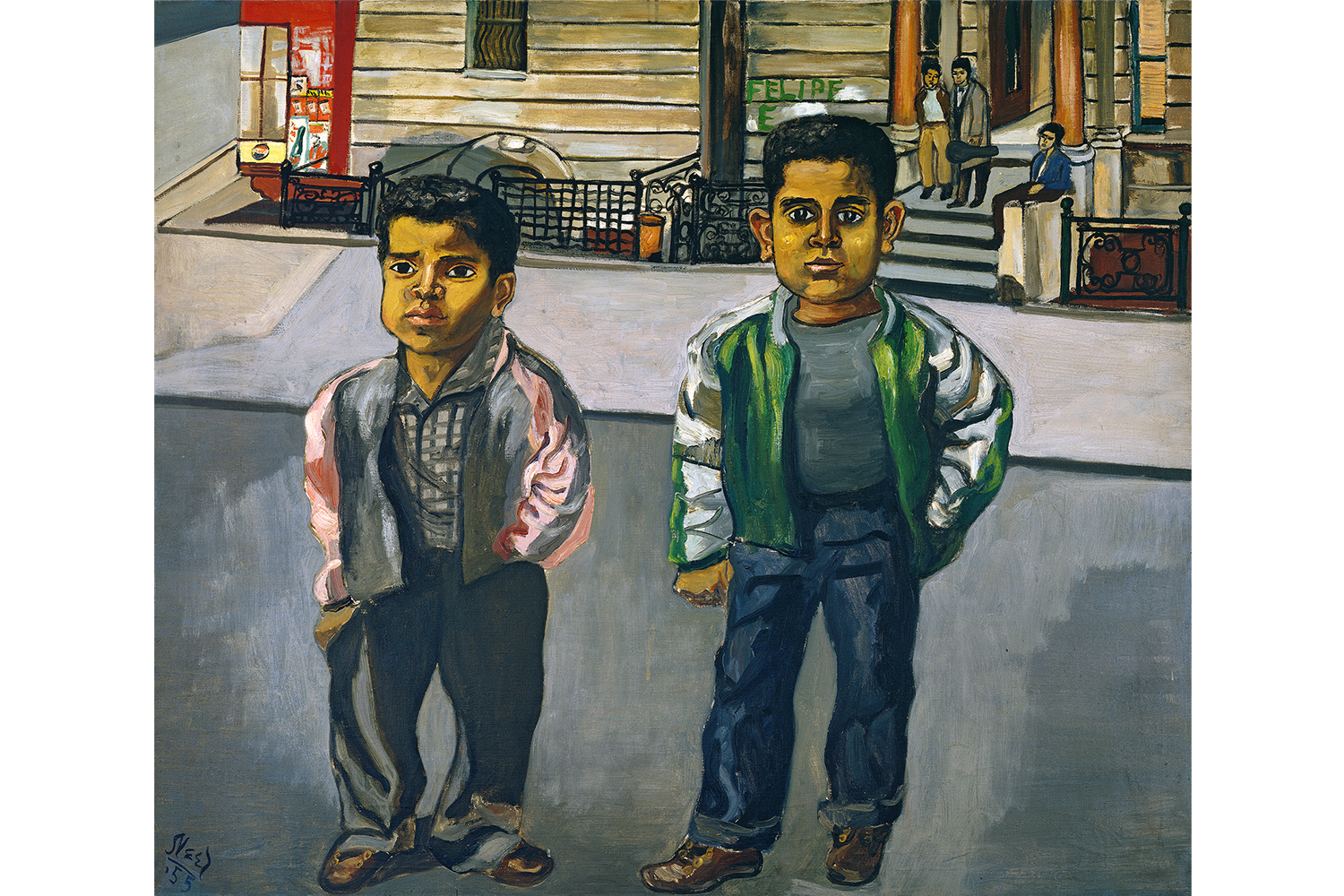

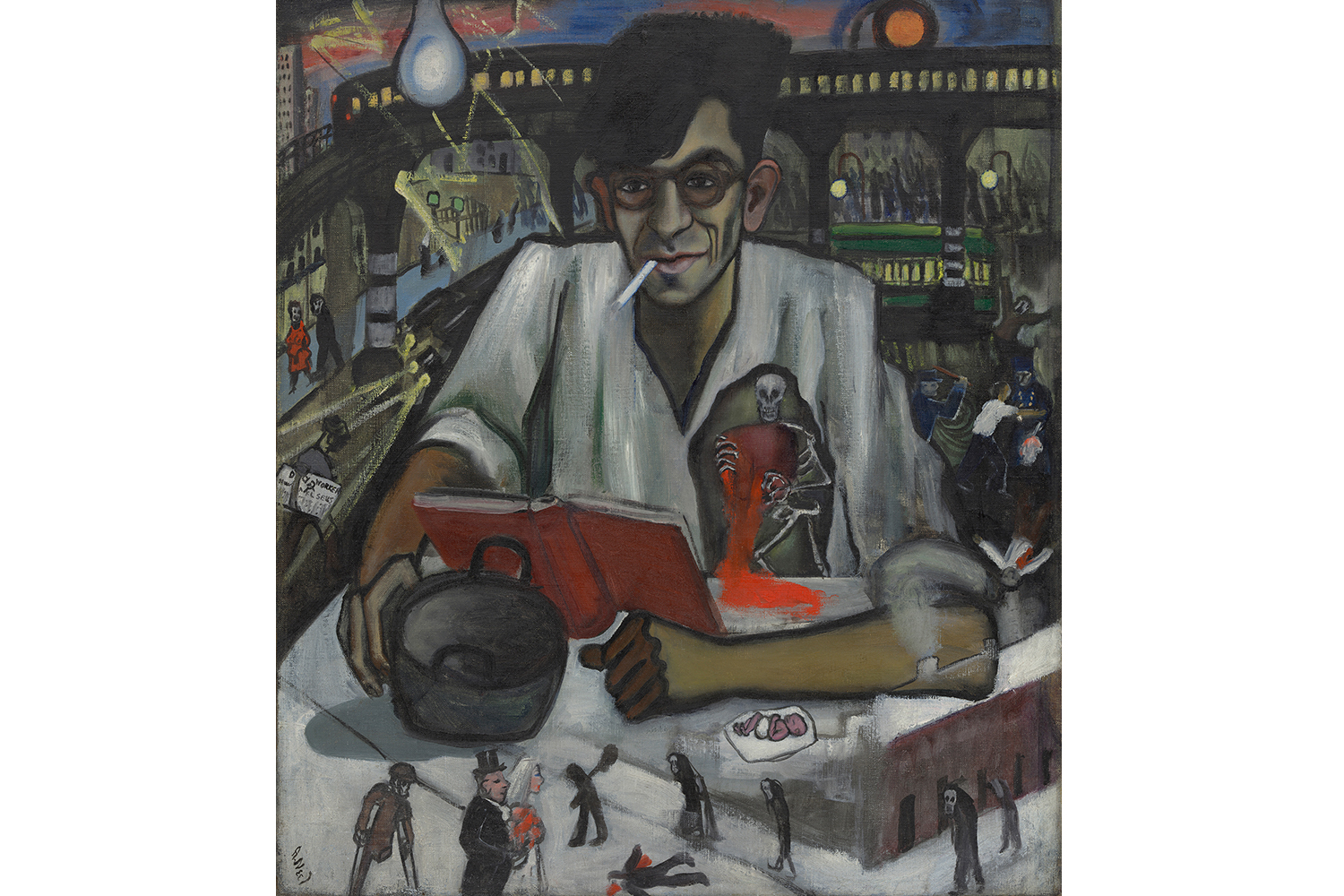

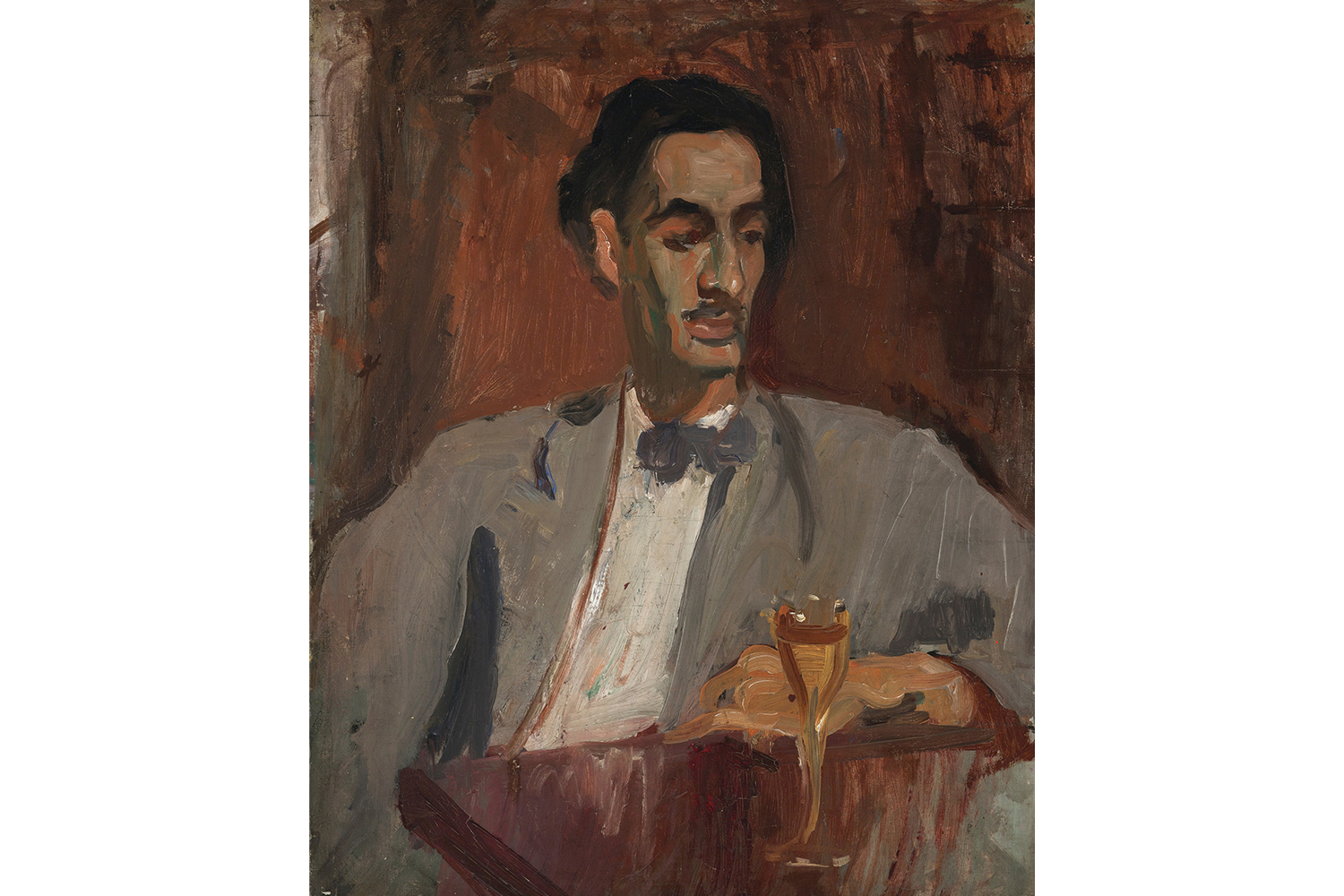

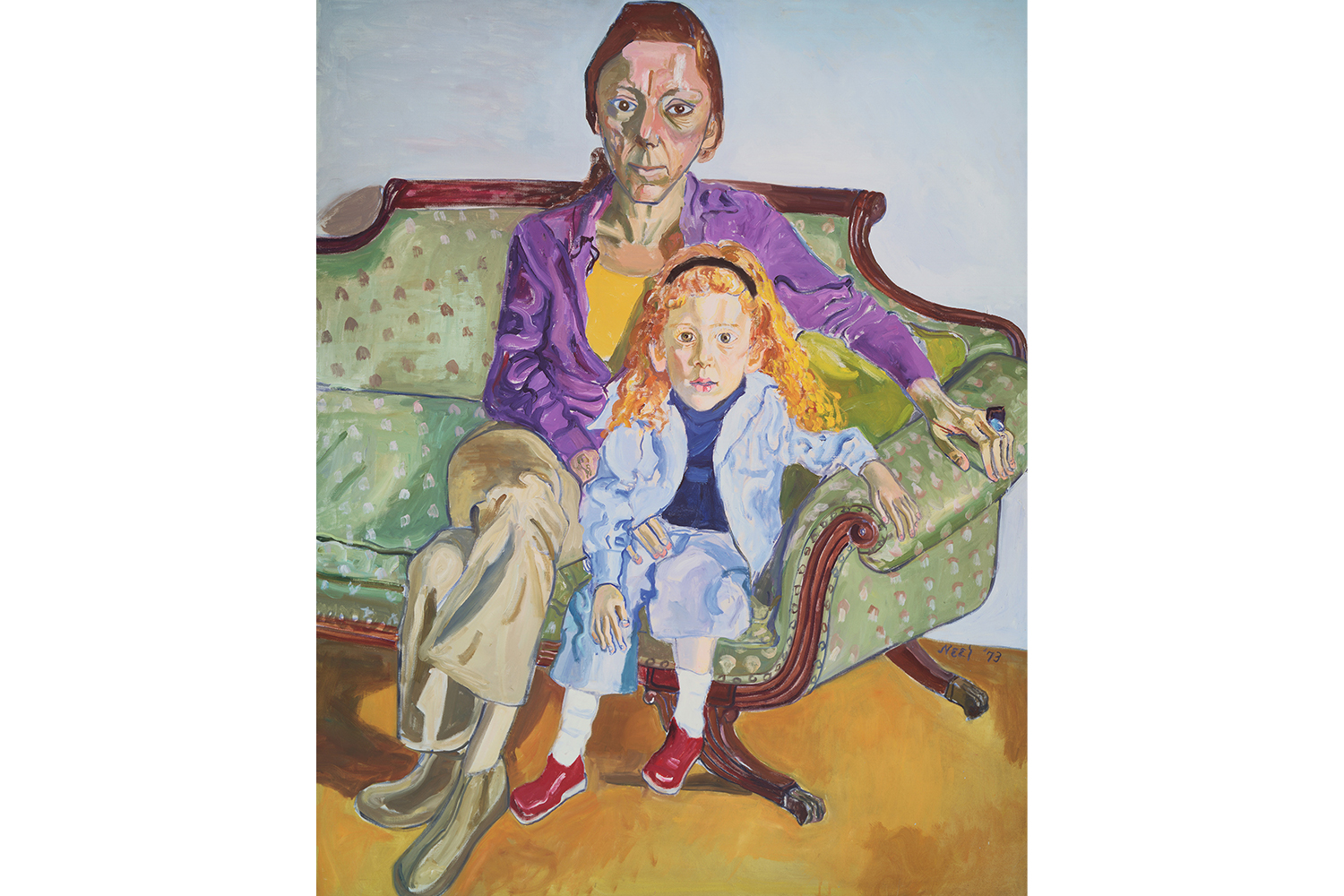

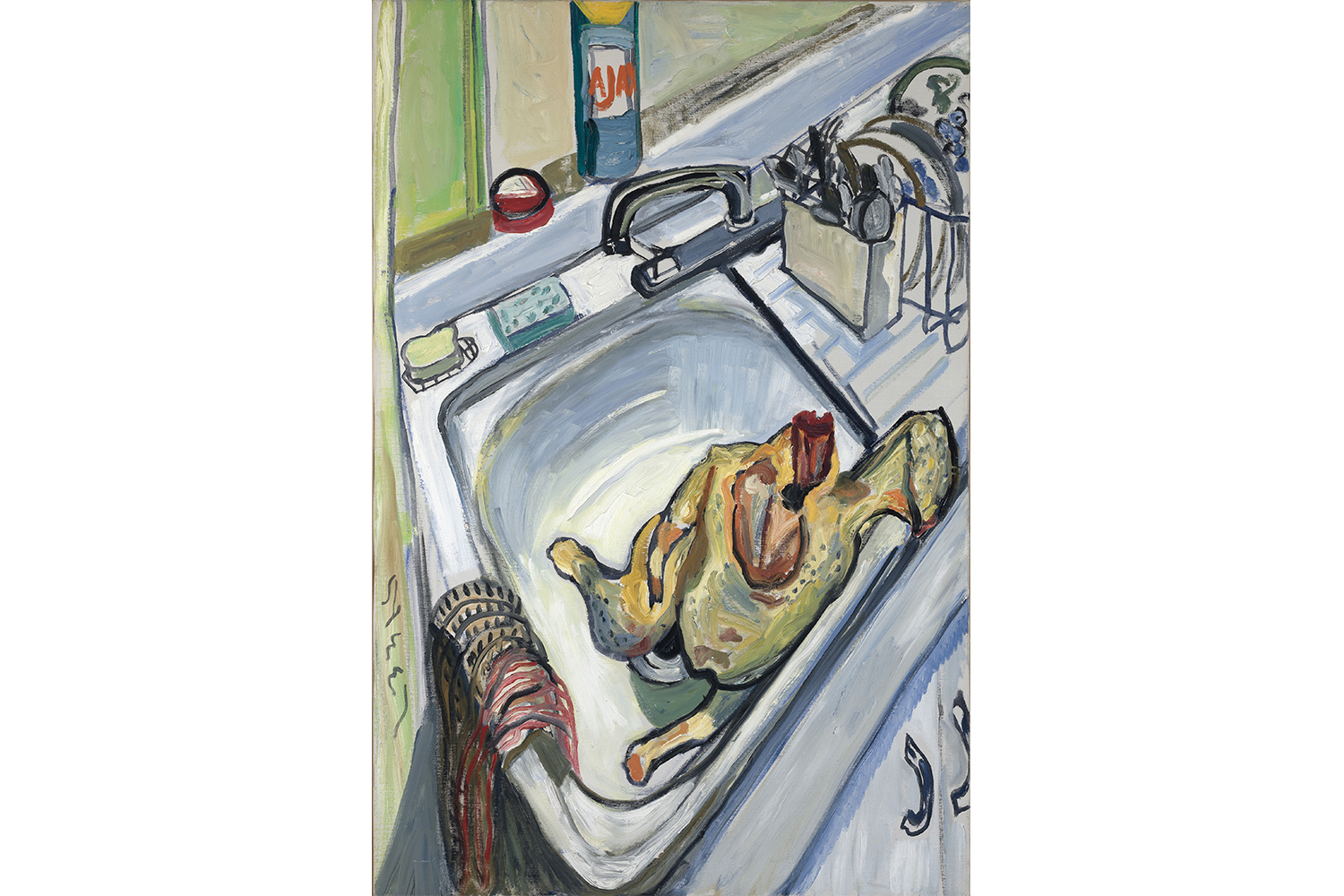

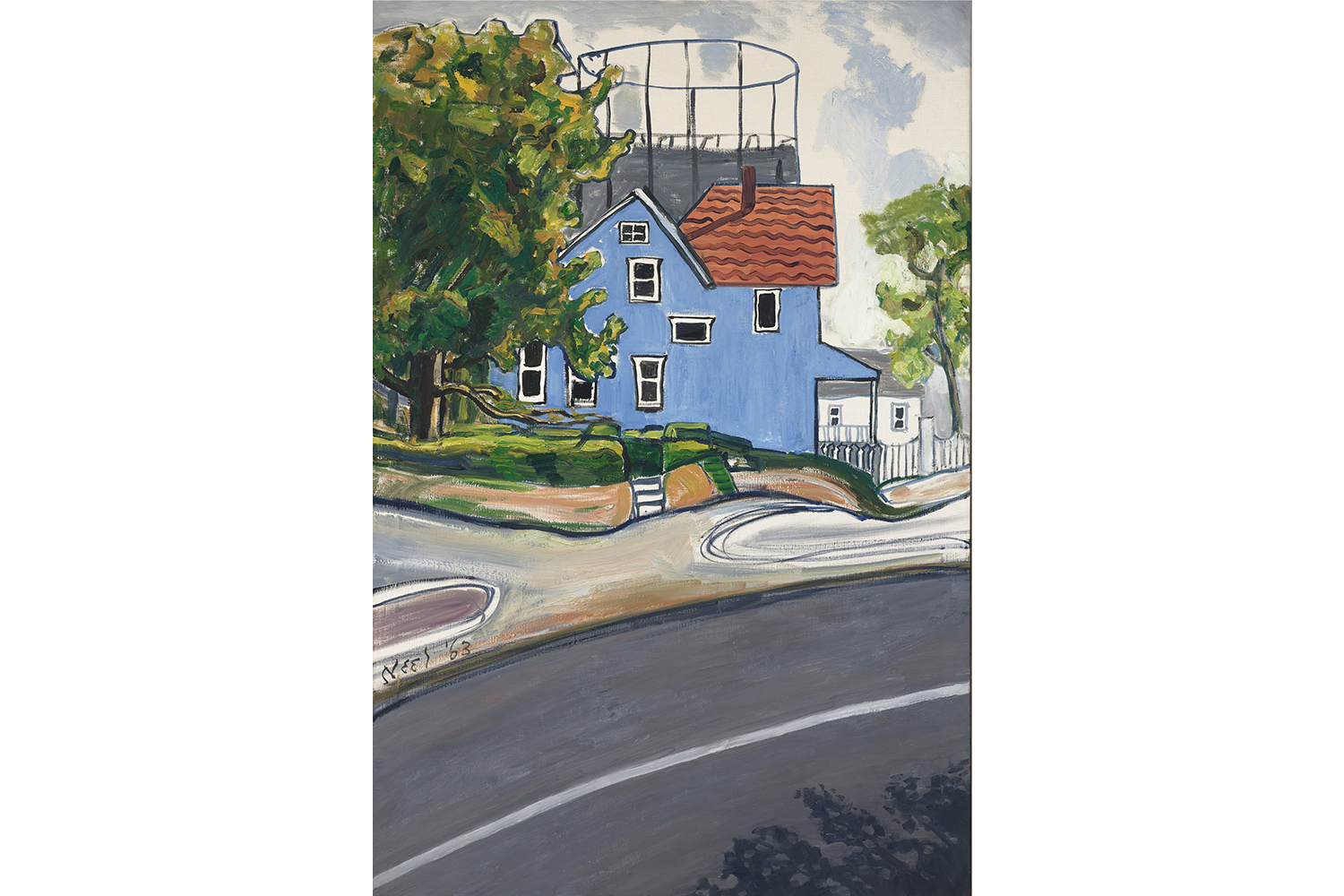

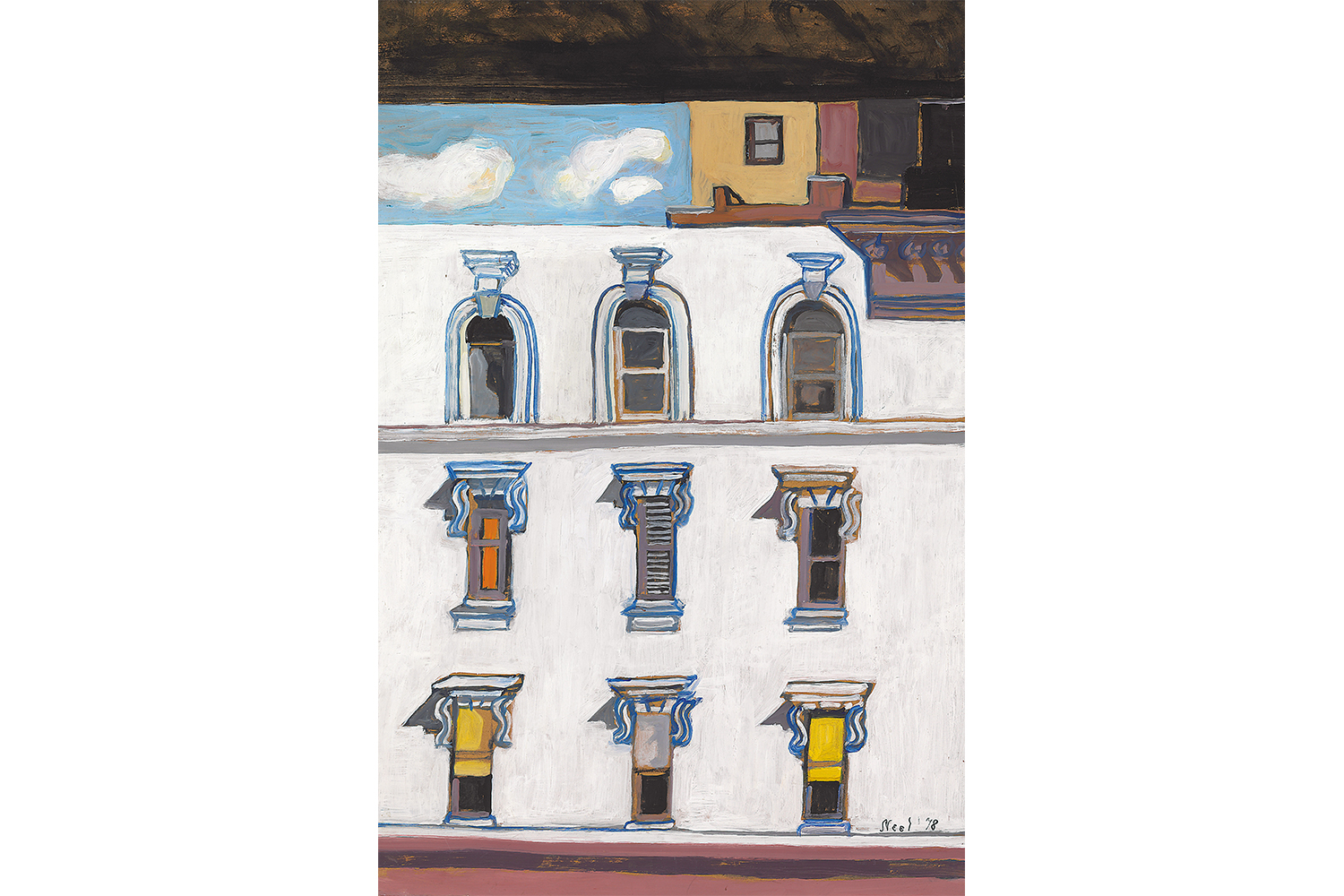

The exhibition “Alice Neel: People Come First” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is the first New York museum retrospective on American artist Alice Neel (1900–1984) in twenty years, and it is massive. It is divided into nine rooms, each dedicated to a theme explored by the artist: after an introductory gallery, viewers may wander through Neel’s fascination with New York City, her years working from home, her fascination with countercultural figures, including activists, communists, and civil-rights leaders she welcomed into her home, and then continue through galleries designated as “The Human Comedy,” “Art as History,” “Motherhood,” “The Nude,” and “Good Abstract Qualities.” Such an approach allows one to grasp the breadth of Neel’s work, but there is also an inconvenience: it can overlook the changes of style and subject matter that the painter went through, from outdoors to indoors, from the masses to the individual, from the political to the universal. One thing remains consistent: Neel always embraced the human condition, one drama at a time. Were the changes in her practice influenced by the different neighborhoods she lived in? Not really, as she had already dedicated herself to painting portraits in the early 1930s, and remained committed to this pursuit in every neighborhood she lived in: first the Bronx, where she lived with her first husband in 1927; then Greenwich Village, where she met many bohemian writers and activists (Kenneth Fearing, 1931) and started to paint political and current events (Nazis Murder Jews, 1936); then Spanish Harlem in 1938, where she fell in love with the vibrancy of the Puerto Rican community that she painted extensively, as well as many figures of the counterculture. Her final residence and studio, secured in 1962, was on the Upper West Side. Neel’s first and foremost landscape of choice was the human face and body. She always painted human beings, with a focus that became more and more microscopic over time; she started painting street scenes of the working class, then went on to portraying ordinary people, family and friends, and, a little later, female nudes, pregnant or not. Her first marriage ended tragically, and that indirectly triggered the latter change of subject matter.

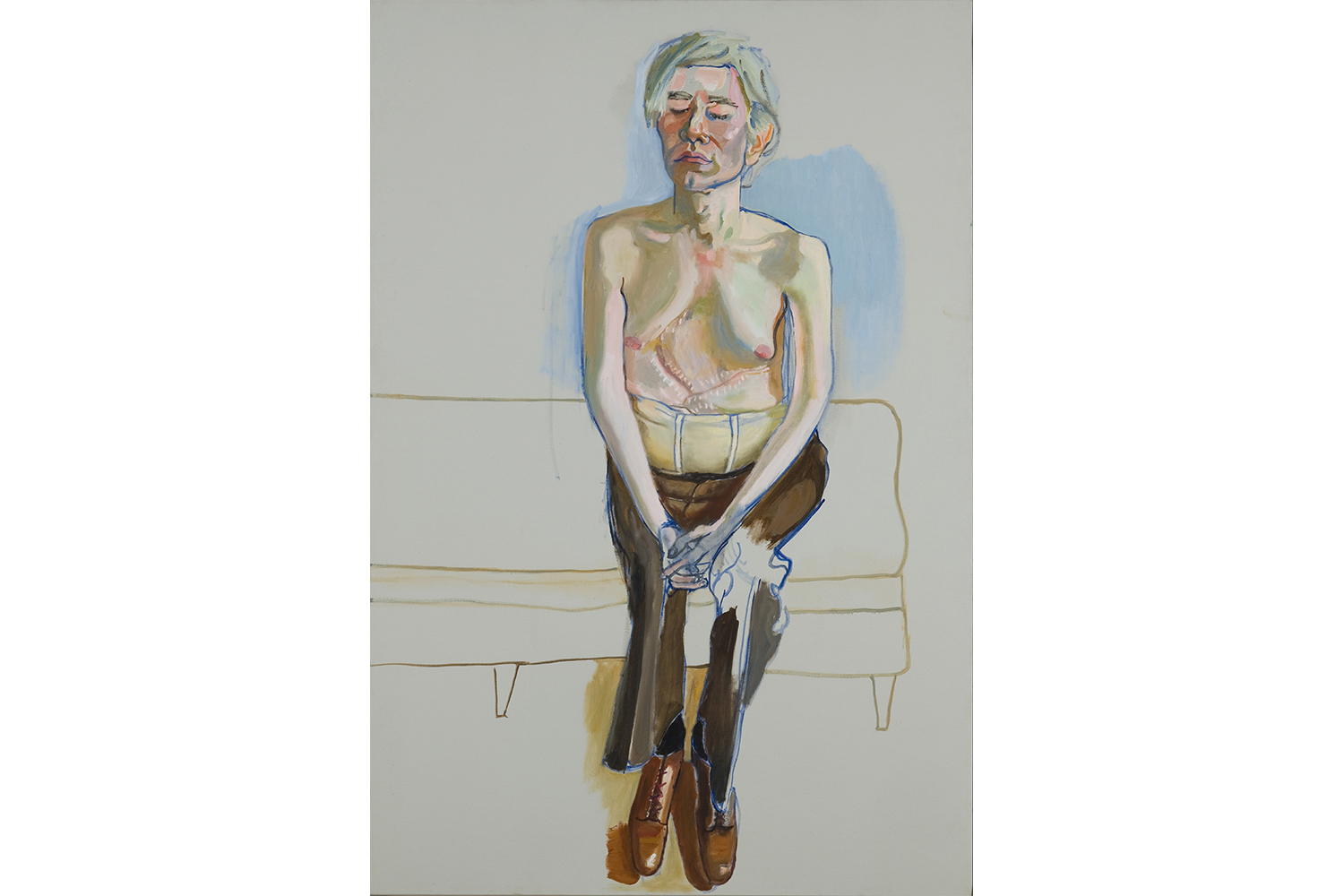

Neel met her husband, Carlos Enriquez, an upper-class Cuban painter, when she was twenty-four in Pennsylvania, where she was born. They soon moved to Havana, Cuba, where Neel got exposed to socialist ideas and found her lifelong political consciousness and commitment to equality. The couple returned to New York in 1927. A year later, they lost their first child to diphtheria, a trauma that would inform Neel’s paintings throughout her entire career. In 1930, pretending to embark on a trip to Paris, Carlos went back to Cuba, taking their second child with him. This event had a shattering impact on Neel: she had a nervous breakdown, was hospitalized, and even attempted suicide. Her life became much more precarious from then on. Shortly afterward, her interest in painting nude women, sometimes bearing child, arose. Neel embraced the female experience: the condition of the single mother raising children, working to sustain a family — indeed, her own struggle. Perhaps she found the strength to keep going in these one-to-one moments in which she would capture the essence of her female subjects. Despite adversity, Neel’s palette seems to turn lighter and more luminous over the years. She started with somber tones, painting scenes of the working class (Longshoremen Returning from Work, 1936) and crucial protests. In addition to the glum content of these paintings, the studio that Alice Neel was living in at the time was very dark, hence the dark tones. In her later years (1970s and 1980s), which were actually more challenging for her, the palette brightens, becomes warmer, almost like a splint of compassion that she would pass along to her subjects, perhaps easing their hustle, pain, or anxiety. Neel also chose to leave areas of her subjects unpainted, a way to leave their personalities unfixed. Through these portraits, was Alice Neel exploring the psychology — or the humanity — of color? Or perhaps it is the other way around: she devoted her life to finding the color of humanity, the radiance of hope, the shades of sympathy.