“Listening In” is a column dedicated to sound, music, and listening practices in contemporary art and its spaces. This section focuses on how listening practices are being investigated and reconfigured by artists working across disciplines in the twenty-first century.

For over a year now, London has been a simmering site of dormant musical gatherings and suspended physical proximities, prompting me to wonder what’s happened to the visceral, tactile energies through which collective musical formations gain so much of their social and emotional force. As Ben Assiter points out, the migration of electronic dance music online during the pandemic accelerated currents that were already underway with the ubiquity of livestream platforms like Boiler Room. With physical assembly prohibited, the dematerialization of collective musical experience gave rise to a whole new level of face-to-screen “participation,” as solitary DJs began broadcasting live from empty clubs to bedroom audiences, who in turn performed “ironic dance floor interaction[s]” in the chat boxes.

If these now normalized experiences point to necessary efforts to make the best of an economically fragile situation in live music, pandemic conditions have also seemingly given rise to a renewed spatial and aesthetic dialogue between electronic dance music and sonic art. Desolate club spaces have become the subject matter of audio-visual pieces such as Tom Andrew and Sam Davis’s VOID: One Year of Silence (2021), soundtracked by Daniel Avery. Panning across empty UK dance floors, dystopian shots of dry ice engulfing deserted black cube spaces are paired with the ringing hiss of post-club aurality, before a synchronized onset of strobe lights and broken beats anthropomorphically resuscitates these familiar-yet-strange architectures. Longer in the making was Detroit DJ/producer Carl Craig’s Party/Afterparty, (2020), an installation built for Dia: Beacon’s club-like basement that moved sonically from collective musical euphoria and daylight breaking in the club to the loneliness and tinnitus that follows. And sonic and audio-visual works have also been brought into nightclubs as a way of making these spaces practically if not financially viable during lockdown. Tamtam’s Eleven songs – Halle am Berghain (2020) enabled the Berlin techno institution to open to the public for the first time in months, for example, while Kode9’s Astro-Darien at the London nightclub Corsica Studios in May 2021 marked the venue’s first opening since March 2020.

In light of these recent intersections, it seems like a good moment to reflect on the longer relationship between sound art, popular culture, and electronic dance music. In the academy, sound art has generally been historicized with recourse to twentieth-century Euro-American experimental music, multimedia art, and electroacoustic composition. Less discussed, perhaps, are the parallel sonic inventions that were taking place across postwar genres such as dub reggae, punk anarchism, and hip-hop, which — at more or less the same time as Max Neuhaus’s Times Square (1977) — opened up a space for a later generation of sound artists. As the proliferation of samplers and drum machines began to democratize music-making in the 1980s, sound art also proliferated in new channels. In the UK, middle- and working-class DIY musicians of white, Black and Asian origins began to experiment with the conceptual and spatial potentials of sound, taking their cues from British dub, soulful and gospel house, (post-)punk industrial, political rap, and the growing warehouse party scene.

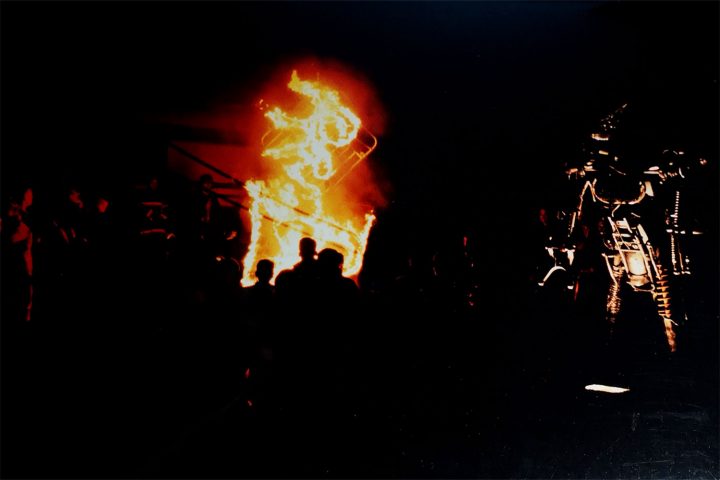

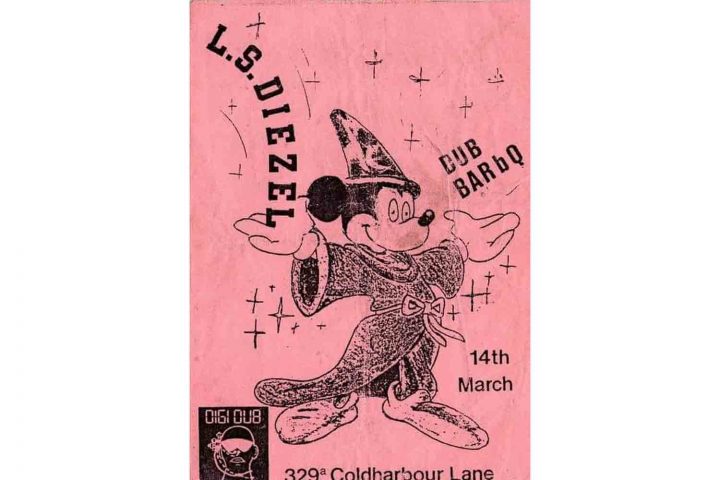

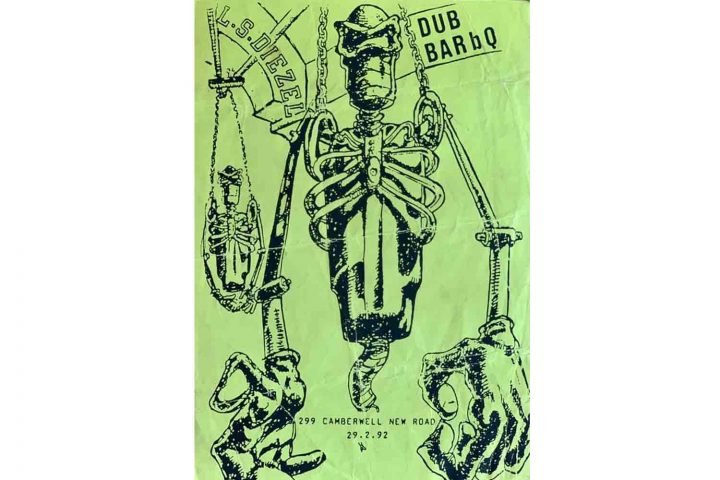

Sound artists of this generation arrived at their practices through hugely varied musical and technical “routes.” South-London-born sound artist Lee Berwick worked as a technician in the 1980s. He was at the famous Einstürzende Neubauten gig at the ICA in 1984; at Scala in King’s Cross when the whole audience wrapped their coats round their heads because Throbbing Gristle were so loud that “you could feel the bones in your chest moving about”; and followed Jah Shaka religiously in the late ’80s, becoming attuned to the highly experimental, physiological, and spatial qualities of dub. With the growing availability of samplers, he started producing dub music himself under his own label, Digidub (est. 1989), creating tracks from the sampled sounds of Routemaster buses and putting out albums with reggae tunes and spatially manipulated soundscapes side by side. It was all about “trying to stand outside of genre,” he told me recently. By the early ’90s, he’d played live Digidub sets to four thousand people at Mutoid Waste parties inside huge installations of exhaust pipes, landed himself a gig creating massive ninety-minute-long ambient drones for flotation tanks, and was on his way to forging a career as a sound artist.

Hailing from a different but roughly simultaneous scene, sound artist/musician Ain Bailey started her career in sound as a DJ playing soul, rare groove, and house music at Black queer parties and at Precious Brown, the night she co-ran with DJ Marilyn in the ’90s, while participating in seminal queer/Black London club nights like Queer Nation and Bootylicious. With Nadine Peters on Thursley Radio she describes the transformative experiences she had at Body & Soul in New York, and how dance music’s functionality, groove, and feel were what led her to experiment artistically with sound. As with Lee, this began as a process of building rhythms out of sampled sounds, but soon expanded into a deeper conceptual interest in the affective propensities of rhythm and in the acts of congregation and gathering that sound makes possible. Listening to “And We’ll Always Be a Disco in the Glow of Love” (2019), which explores how grief is “sonified” through musical attachment, and to her performance at Wysing Arts Centre in 2016, which splices together the introductions from lovers’ rock tunes to signal the moment when people asked each other to dance at a blues party, her creative process remains shot through with the affective power of dance/music and its ability to bind us to others in relations of love and loss, celebration and mourning.

Manchester-born sound artist Wajid Yaseen started out as a bookkeeper for Mute/Sonet Records in the late ’80s. A participant in electro and EBM, his discovery of Nitzer Ebb was formative to his understanding of music as something that’s not just about entertainment but about being “fucking furious.” Bookkeeping for Mute exposed him to the punk spirit through artists who were using DIY instruments to make angry industrial racket and carve out a lineage different from Cage’s musicalization of sound. In the mid-1990s, Aki Nawaz of Fun-Da-Mental — dubbed the Asian Public Enemy — poached Wajid to play bass for them, despite the fact that he’d only ever strummed one in his bedroom; and it was off the back of touring with Fun-Da-Mental that Wajid was able to start his own musical project, 2nd Gen, using samplers and found instruments to explore noise, distortion, aggression, space, and texture. Parallel to what Lee described as a desire to escape genrefication, however, he sought to break away from the “trapping” culture of music production through interdisciplinary collaboration with a dancer, marking the point at which sound became conceptual for him. When he eventually stumbled into sonic arts as a discipline in the 2000s, he knew nothing about Cage or the institutionalized history of his practice.

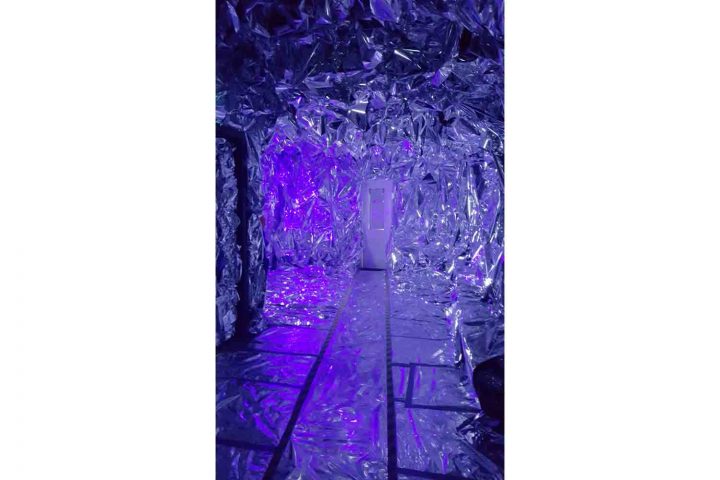

These examples bring out how sound art has partially evolved through diasporic and Black-originating genres like Jamaican dub, African and Latin house, and British Asian hip-hop; the harsher sounds of punk and industrial; and the capital-driven settings of recording studios and record labels. Moreover, such connections have had a spatial as well as aesthetic dimension, with sound installations occupying nightclubs and warehouse parties across the UK and Europe in the late ’80s and ’90s. As Lee recalled, the ambient drones he’d created for float tanks not only found their way into the “chillout” rooms at squat parties in South London but also became a way of opening Digidub club nights: the drones would start low, gradually becoming massive over the course of ninety minutes, as promoters and audience members grew increasingly “edgy.” Finally, the sound would break into 1970s roots reggae, and then jungle, before Digidub slammed a live set. “For me, that was sound art straight in the nightclub,” Lee explained: a way of thwarting people’s expectations and testing their aural affective thresholds.

In the academy, the multiple anticipatory interrelations between popular/dance music and sound art are still seemingly overshadowed by older (and whiter) histories pertaining to the Euro-American experimental avant-garde and post-medium art. To my mind, the sonic biographies of sound artists like Lee, Ain, and Wajid, the space opened up by Black experimental genres like dub, hip-hop, and house music, and the presence of sound art at warehouse raves alongside hardcore breakbeat in the 1980s and ’90s, indicate sound art’s incredible diversity as a field, its distinctly unstable aesthetic and socio-spatial boundaries, and its multiple protagonists and genealogies, which continue to swell in new directions. To some degree, this provides a context for the pre-pandemic London club night Ø, co-curated by Kode9 and Shannen SP at Corsica Studios (2017-20), which brought audio-visual installations into a spatial-aesthetic relationship with jungle, footwork, and other Afro-, Asian, and Latinx diasporic dance music. Oriented around alternative futurisms, lineups featured works such as Amra’s The Jodhpur Boom (2019), a sonic speculation on the 2012 Jodhpur sonic boom, and GAIKA and Rob Heppell’s Lamborghini Copz (2019), on the cybernetic relations between law, race, and power in the year 2120, as well as Afrofuturist staples like Akomfrah’s The Last Angel of History (1996). Meanwhile, in Room 2, musicians like South African duo Manthe Ribane and Okzharp, Congolese-Belgian DJ Nkisi, and Shannen SP herself provided sound worlds ranging from Afro-gabber and gothic dancehall to kuduro and gqom.

Unlike older raves, Ø took place on a weeknight and was generally not hedonistic. Where it felt connected to the above histories was in its provision of a space for sound installations whose aesthetics and thematics were integrally bound up with diasporic cultural exchange, Black experimental and popular musics, and dance/club spaces; and for artists who don’t necessarily see their practices as arts- or gallery-associated. Significantly, Ø also drew genuinely diverse audiences in terms of race, class, sexuality, and gender, some of whom felt unable or unwilling to participate in the mainstream art world, and who, in coming to see El B or Klein, found themselves exposed to a wide range of installational and performance art, often by artists of color. A nexus between the multiple pasts and futures of sound art, perhaps it was this double movement of stretching both the art institution and the night club beyond their often intensely genrefied milieux that made Ø feel particularly optimistic, and that makes its legacy so significant at a time when music’s performance spaces are preparing to reopen.