At the turn of the millennium, Guillaume Dustan was a spark plug of queer issues. His autofictional debut novel made him a celebrated young writer, and he became an outspoken voice for pleasure-seeking in the firmly entrenched AIDS crisis. His advocacy of bareback sex put him at odds with some gay activists, like ACT UP, and he was a vocal and visible public figure, with regular TV appearances in France and internationally. When he died, just shy of forty years old in 2005, he left behind both a sense of mourning for promise lost and a trove of personal and professional connections and tangible work that is still being sorted and reassessed. Semiotext(e) has recently re-released his first three novels in English, and Fri Art’s peculiar exhibition-cum-research center/casual hangout lounge has established an intention to shed light on “a part of his oeuvre that is little-known to date.”

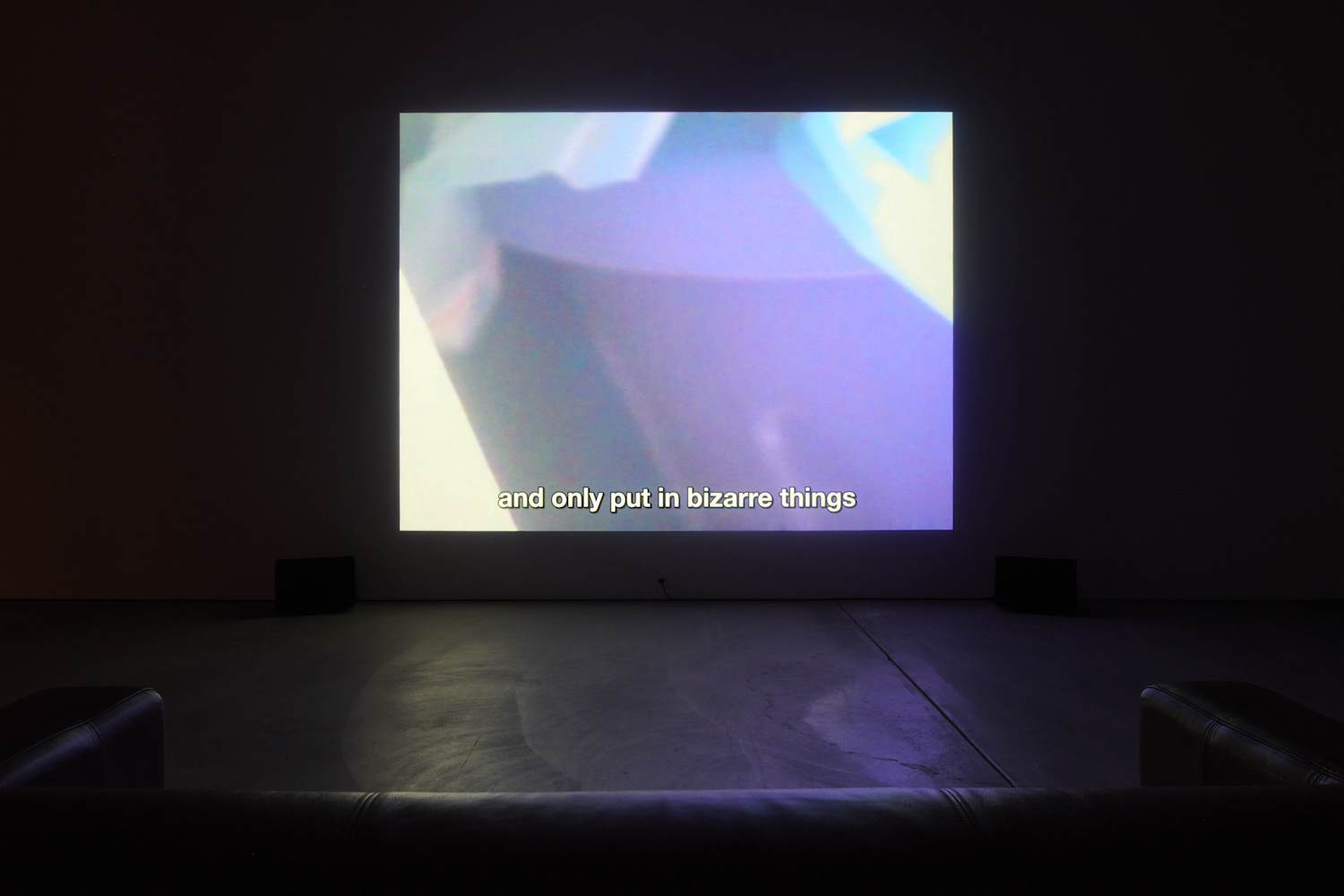

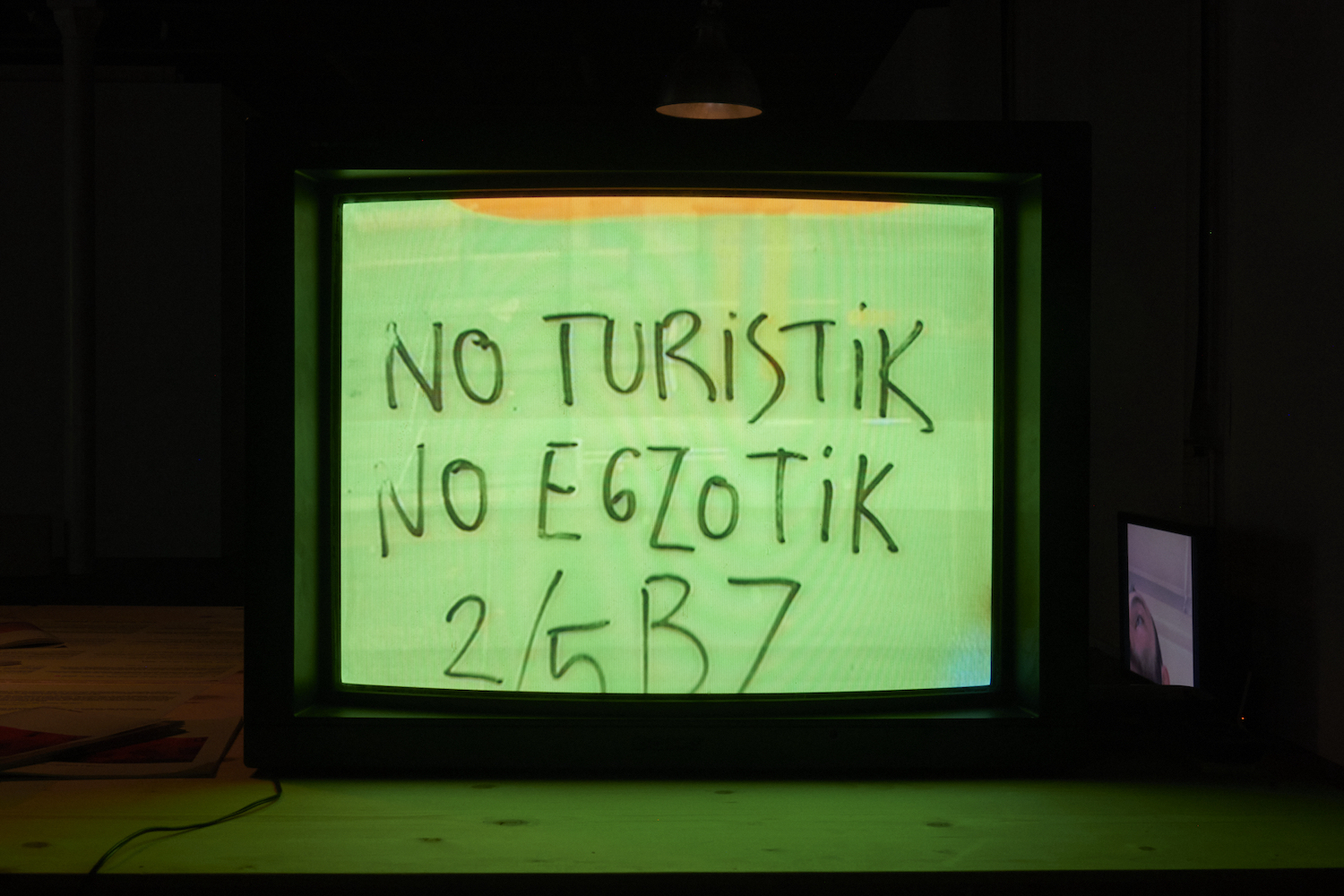

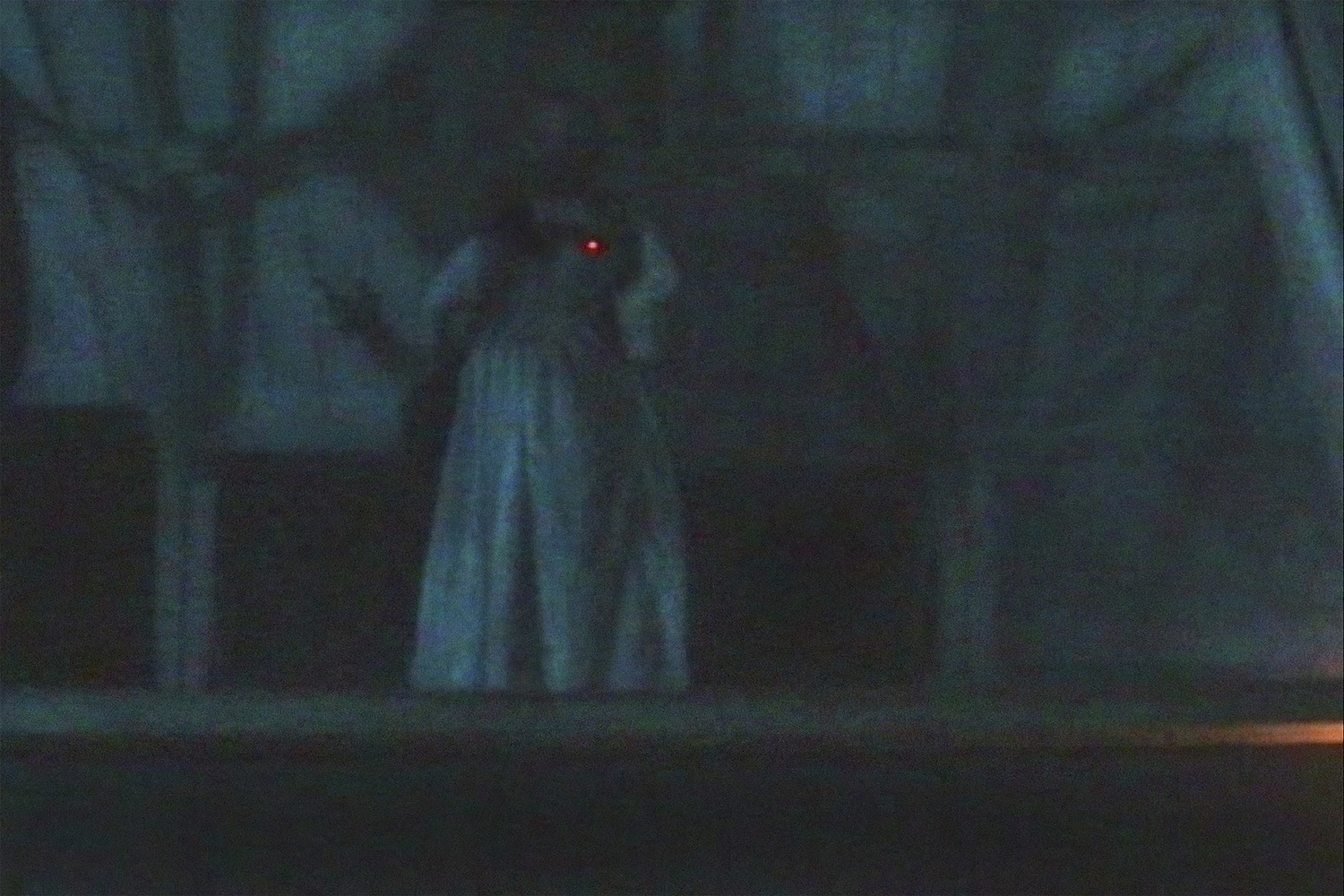

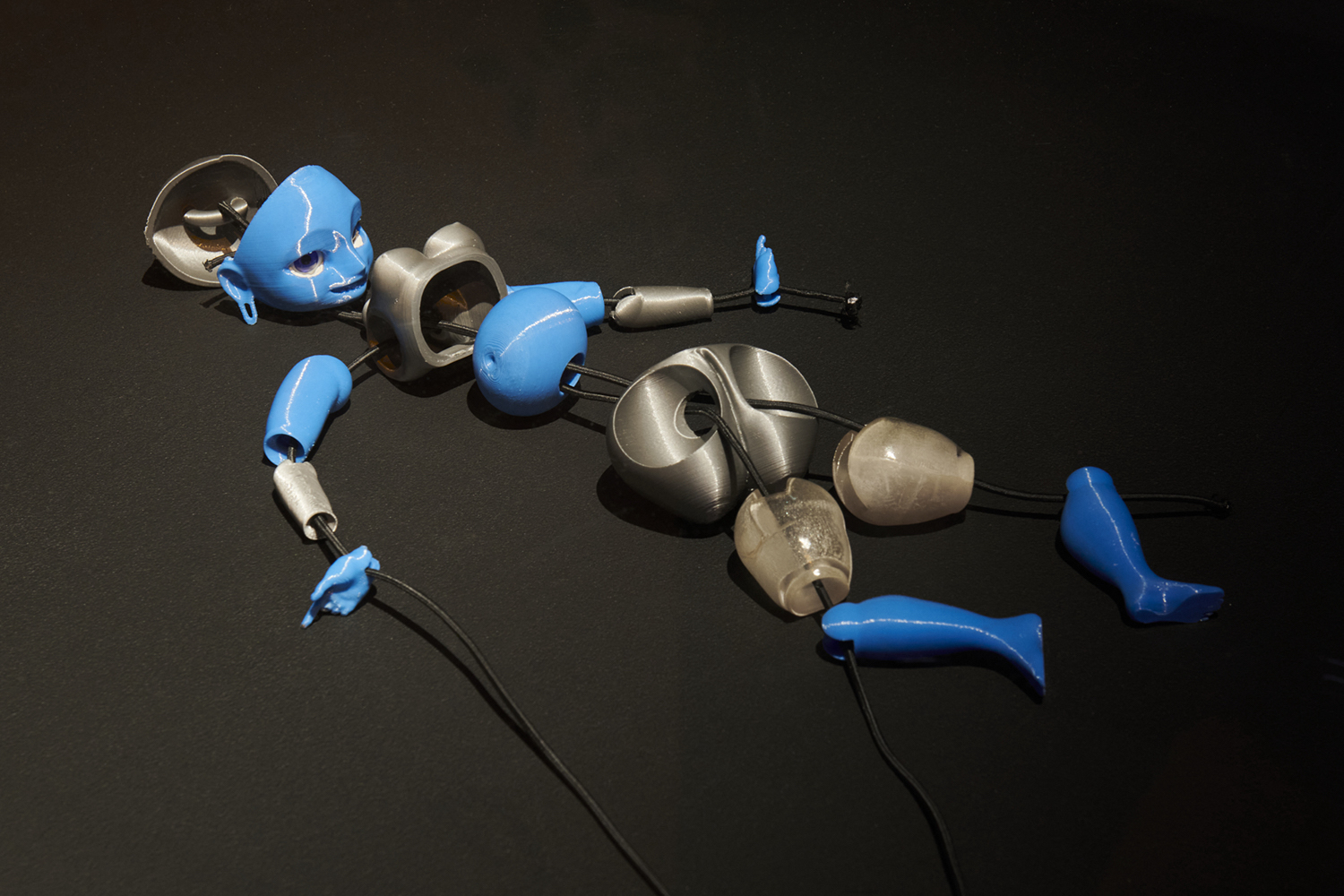

The project does this by generously tackling all of Dustan’s oeuvre, and part of its success is in the multiple entry points this allows. Between 2000 and 2004, Dustan, using a portable digital camera, made nineteen films, thirteen of which are on view here, although they’re difficult to place as either art or cinema. In the exhibition they are either projected large or displayed on tabletop monitors as in a small research center. Comfy, heavily used sofas suggest abstracted living rooms for viewing. The films — really more akin to home videos — can be graphically sexual, although, like his writings, are often calm and considered. This placidity is disarming when viewing a giant penis wedged into a ball-and-cock ring being stroked while a narrator complains about the length of time it takes to climax. A long table has all of the sixty or so books by other queer writers that Dustan edited as part of Le Rayon, the first LGBTQ imprint in France. The effect is like a reading room that is at the same time insistent upon the physical and sculptural legacy of Dustan’s labor. A computer in a small back room features press and photos in folders for exploration. It’s not so much an exhibition of something as it is an exhibition that is something: an environment, a library, a reminder of something overlooked.

Fribourg is a small cliffside city in the center of Switzerland, and this institution sits at its base with majestic views and some towering claustrophobia. Dustan visited the city in 1999 for European Gay Pride and fell in love with Tristan Cerf. For Dustan, this Swiss man and Switzerland became an idea of utopia, where he could be a gay man who is happy. This is conveyed by some films, and the exhibition gently ties this towering figure to the local, woven into queer lives even in a country that often presents itself as a conservative bastion of Western Europe. This is, of course, the power of smaller art venues like Fri Art: experimental exhibits such as this may speak to many specifics, leaving their own lasting impressions and hopeful visions.