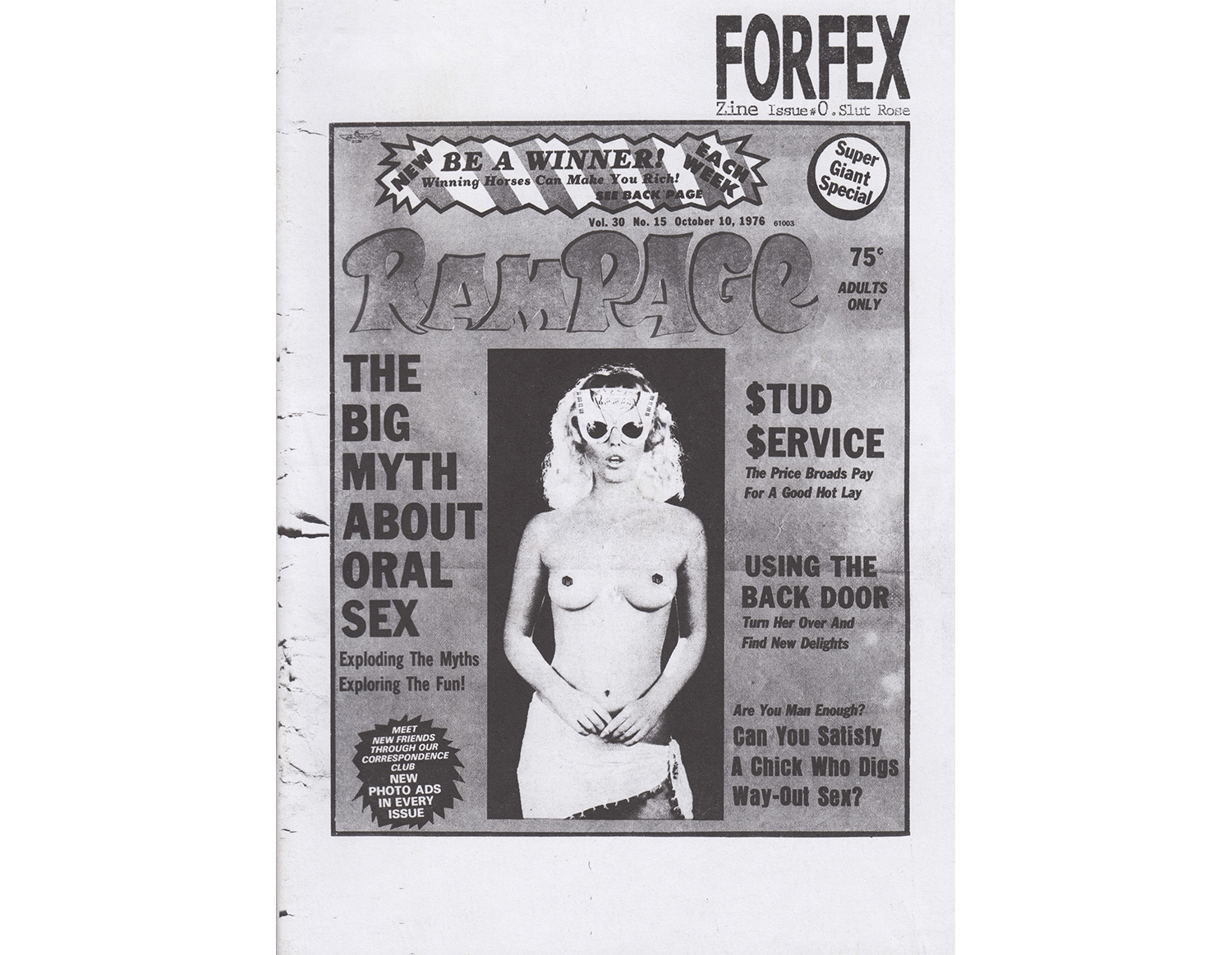

Thirty years of passion and clothes. Street fashion and culture in the 1980s was a vision belonging to the crazy and the damned, a generation of people who were dying of AIDS and glory, who would never have imagined that in a few decades their style would become one of the most pervasive influences on fashion today. Luca Benini, founder of Slam Jam, talks about his start, post-punk and post-freak Italy in the 1980s, and his collaboration with Nationhood to gather thirty years of his archive in one digital experience.

Videoshooting from Namaskàr, India. Video produced by Slam Jam. Directed by Giacomo Zanni and Emiliano Mazzoni – Dvd/Video collection, 2007.

Gea Politi: British (and American) punk was a niche movement that exploded as fashion and imagery in 1970s London. On the other hand, punk in Italy has always been seen as a “subversive movement.” What was it really like?

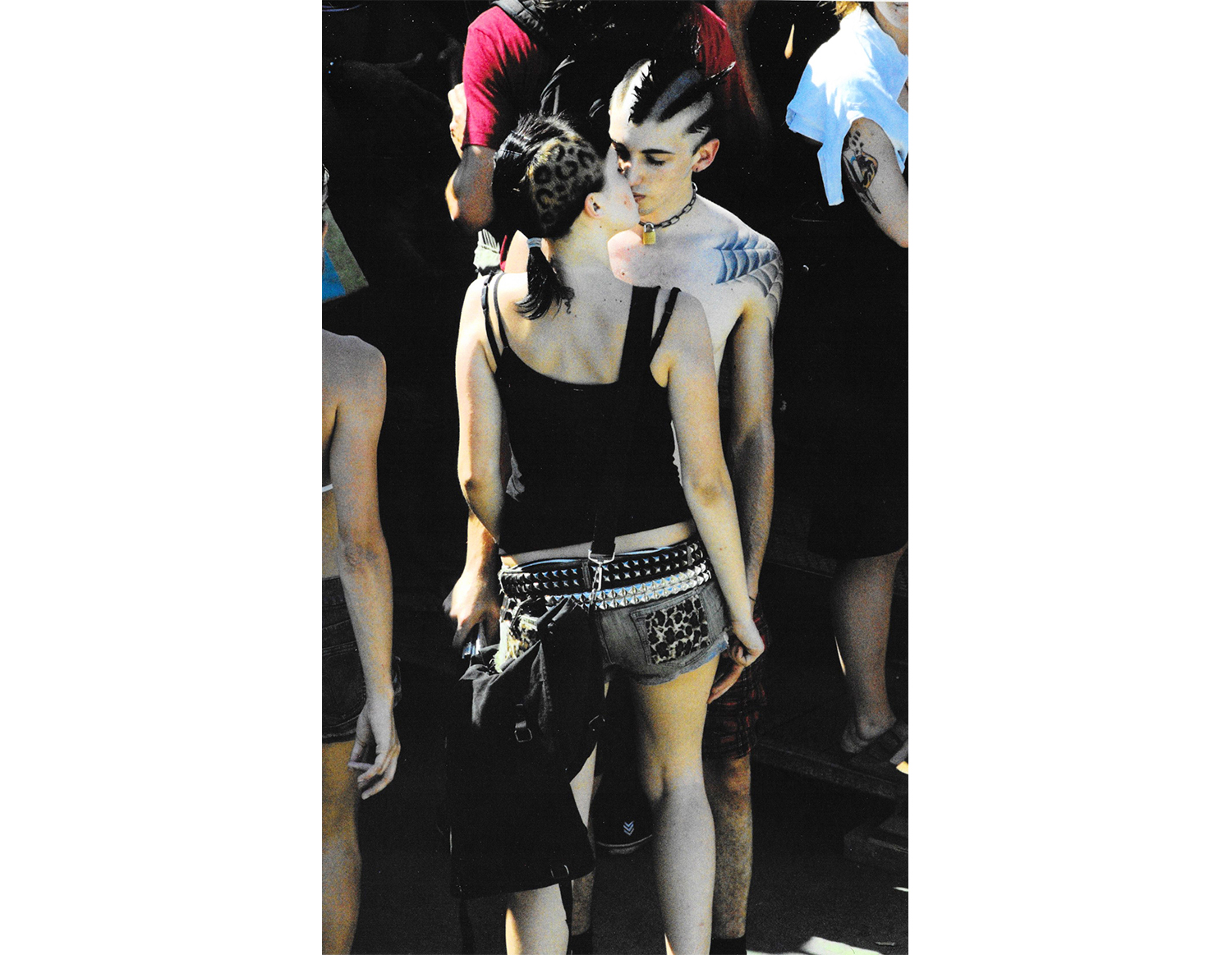

Luca Benini: In 1977 I was fifteen years old, so I was very sensitive to changes. One Sunday afternoon I saw a musical program on television presented by Renzo Arbore and Gianni Boncompagni, where I was struck by its beautiful setting with a wall made of speakers and, out of the blue, Renzo Arbore introduced the British band Sex Pistols. Living in a small town of 1500 inhabitants in the province of Ferrara, seeing them shocked me, musically and aesthetically. They wore leather pants, chains, and handkerchiefs tied on their head. Punk in Italy, compared to the United States and England, seemed slightly out of context. In Italy in those years there was a very strong movement instead, which emerged from the disillusionment following ’77. It was very much felt and widely understood by Italian culture. In the early ’80s, many interesting bands like CCCP Fedeli Alla Linea tried to develop the current of thought and life that was typically punk, but it was not received as in London. Even in numbers, it remained a niche music and lifestyle, not understood and adopted by the masses.

GP: Ferrara is your hometown. How did you experience it in the 1980s? What did you love and what did you hate?

LB: Ferrara is a very beautiful but extremely bourgeois city. I never lived it as a city so much; in the early ’80s I was living an emotional moment of isolation, which did not stimulate me to go out. I definitely found pleasure and excitement in Bologna, and in the Riviera Romagnola. Ferrara, due to its provincial nature, was a rather static city, not as dynamic as nearby Bologna. Between the late ’70s and early ’80s, in Bologna there was a very powerful climate. Just think of moments like Radio Alice, Traum Fabrik, Gaz Nevada, and so on. When they opened L’Isola nel Kantiere a few years later, a social center among the most famous and with a seminal impact for the national underground scene, I felt a strong energy. I used to spend Friday nights there and Saturdays at Aleph in Gabicce (later Ethos Mama Club), clubs with very different scenes, two opposite places if you like, but in my way of seeing they were complementary. That decade for me was fundamental from the point of view of subcultures and music. Genres that still exist today were born: new wave, hip-hop, house, and so on. I remember that in 1988 I thought that the first house music I listened to in the clubs on the Riviera could not last more than two years, given the volatility of the trends we were used to. There were so many changes in that decade that I probably liked the things I used to hate, and vice versa. I never went to university, but living as I did in that decade was like attending it, master’s degree included.

GP: About the ’80s, for those who did not live through them, there are distorted views. Many, from the outside, see a period of abundance and exaggeration. Few remember what was happening in the subculture. For example, underground and streetwear were already very present in the imagination of Generation X. Can you tell us what were the highlights for you in fashion during that decade?

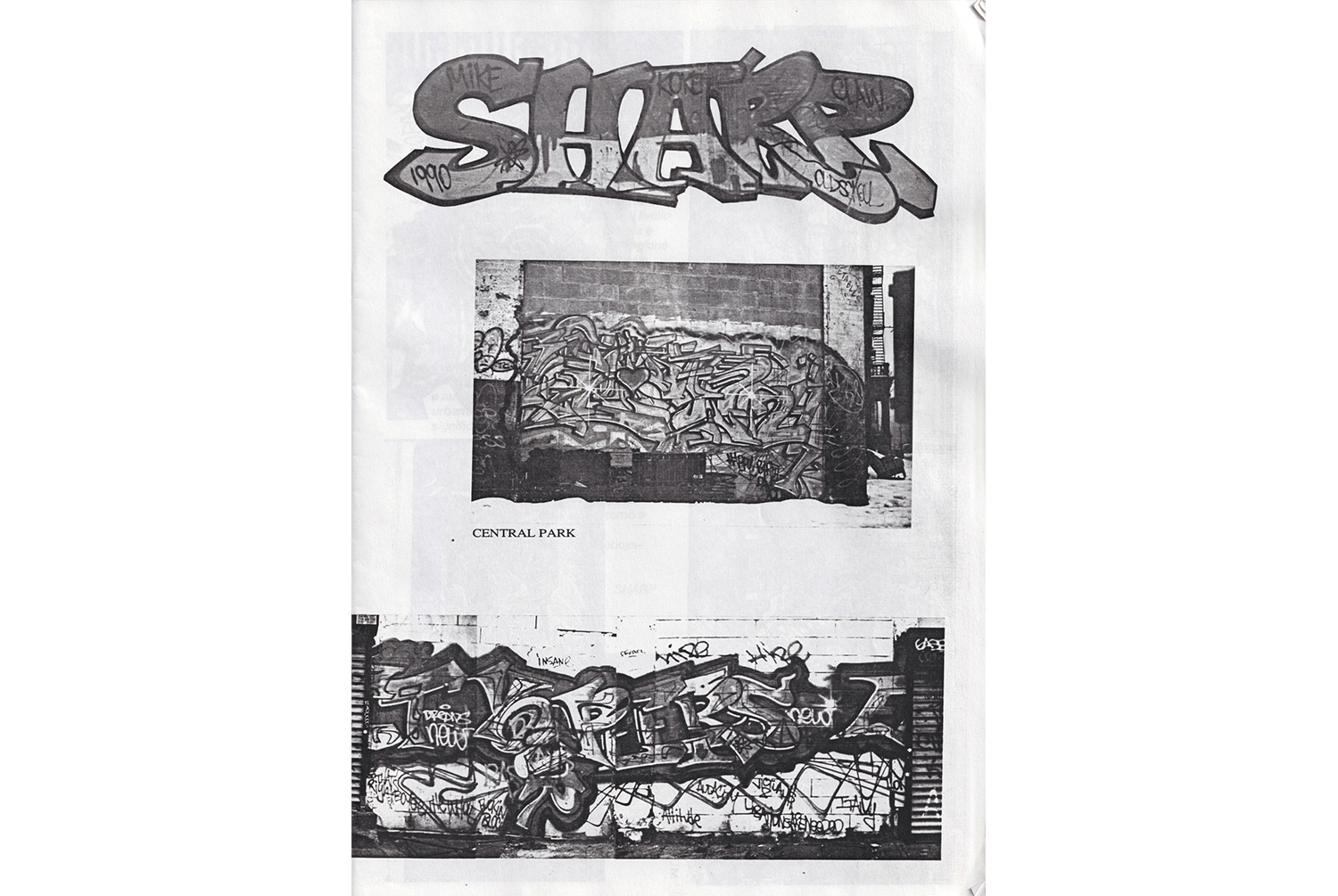

LB: Surely the most salient moments were the birth of hip-hop culture and house music, with associated derivations that have influenced and contaminated the forty years to come.

GP: What pushed you to create Slam Jam? Was it the result of a lack of a specific language that you were looking for (or that you found elsewhere) and that you wanted to bring back to Italy, adapting it to our culture?

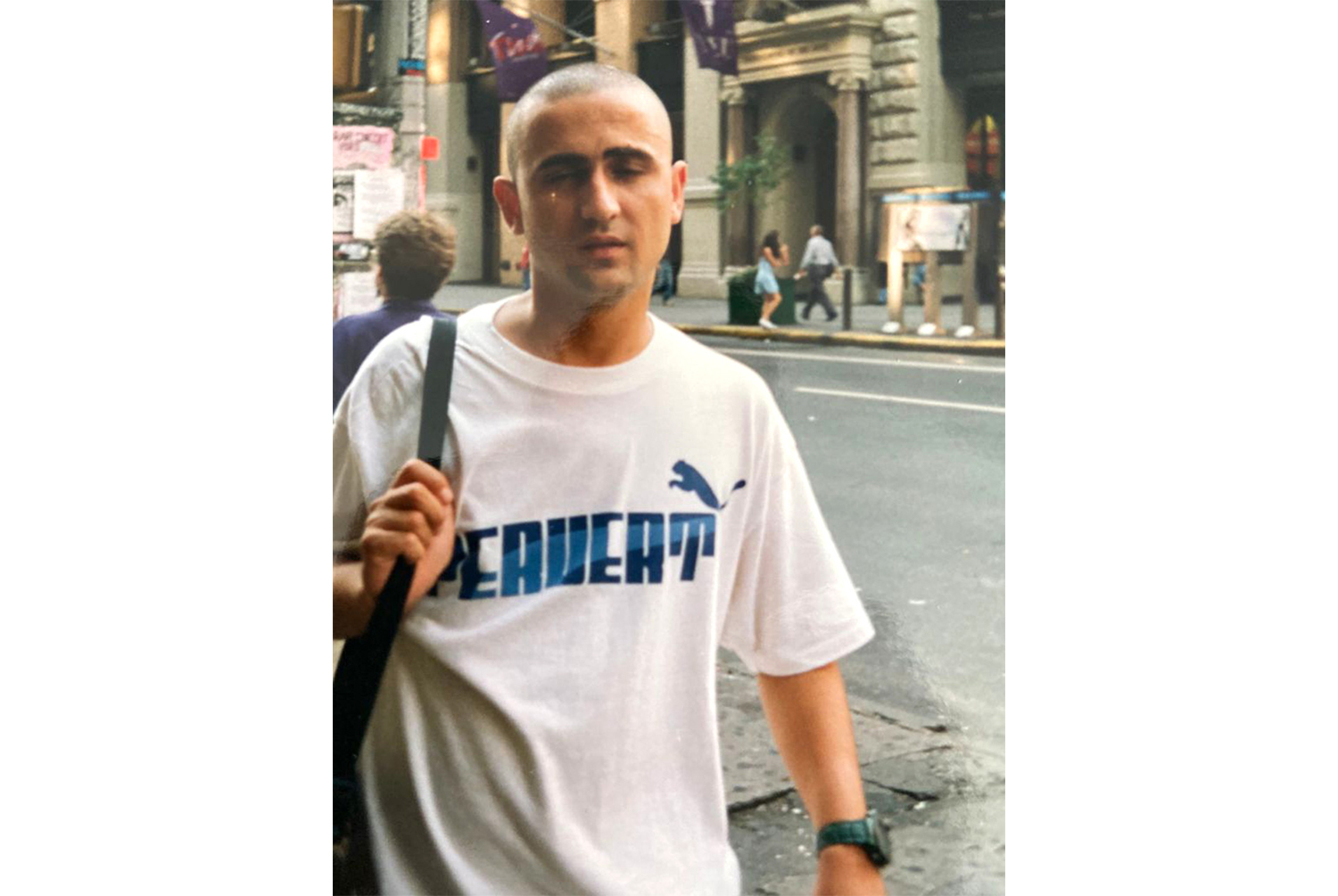

LB: The first time I realized there was a universe made of clothes I was with my mother in my childhood home. When I was eight years old, I told her that I wanted to be involved with clothing. I really think I was born to do this. I lived in the countryside, my mother was a farmer and my father a builder, there were only two channels on TV, but anyway I was very clear about what I wanted to do. After starting out as a salesman in a store that sold Fiorucci among others, in the early ’80s I became a sales agent working with various multi-brand showrooms representing Italian fashion icons such as Armani, Versace, Enrico Coveri, and so on. However, I felt that something was missing, such as context and the energy that came with it, often in the form of music, which had always been my beacon. In that world it was mainly about clothes, and it was a scenario in which red, for example, was already considered a transgressive color. As much as I respected this enormously, I was looking for something that went beyond the product. This urgency pushed me to travel from New York to London, and then Tokyo, to realize that there were realities where clothes were the vehicle of a very wide message, which included music, art, skateboarding, and much more.

GP: What was your community in the early years and how has it evolved today? Who chose to follow Slam Jam?

LB: My community was mostly made up of people who frequented subculture venues: graffiti artists, musicians, and the skate scene. These were the people who approached Slam Jam from the beginning, for natural reasons of cultural and geographical proximity. Today the community has changed and evolved a lot, also thanks to the media. The world of subcultures remains, but they are still contaminated and constantly changing. At the base of Slam Jam’s dialogue with its community remains the desire for authenticity and a lifestyle that follows this track; in fact, only the form has changed over time, and will continue to do so.

GP: “The innermost motive of the collector may be: he undertakes a struggle against dispersion. The great collector is originally touched by the confusion, by the fragmentary nature in which things in this world are found.” This is one of Walter Benjamin’s definitions of the identity of the collector. How do you position yourself with respect to this position?

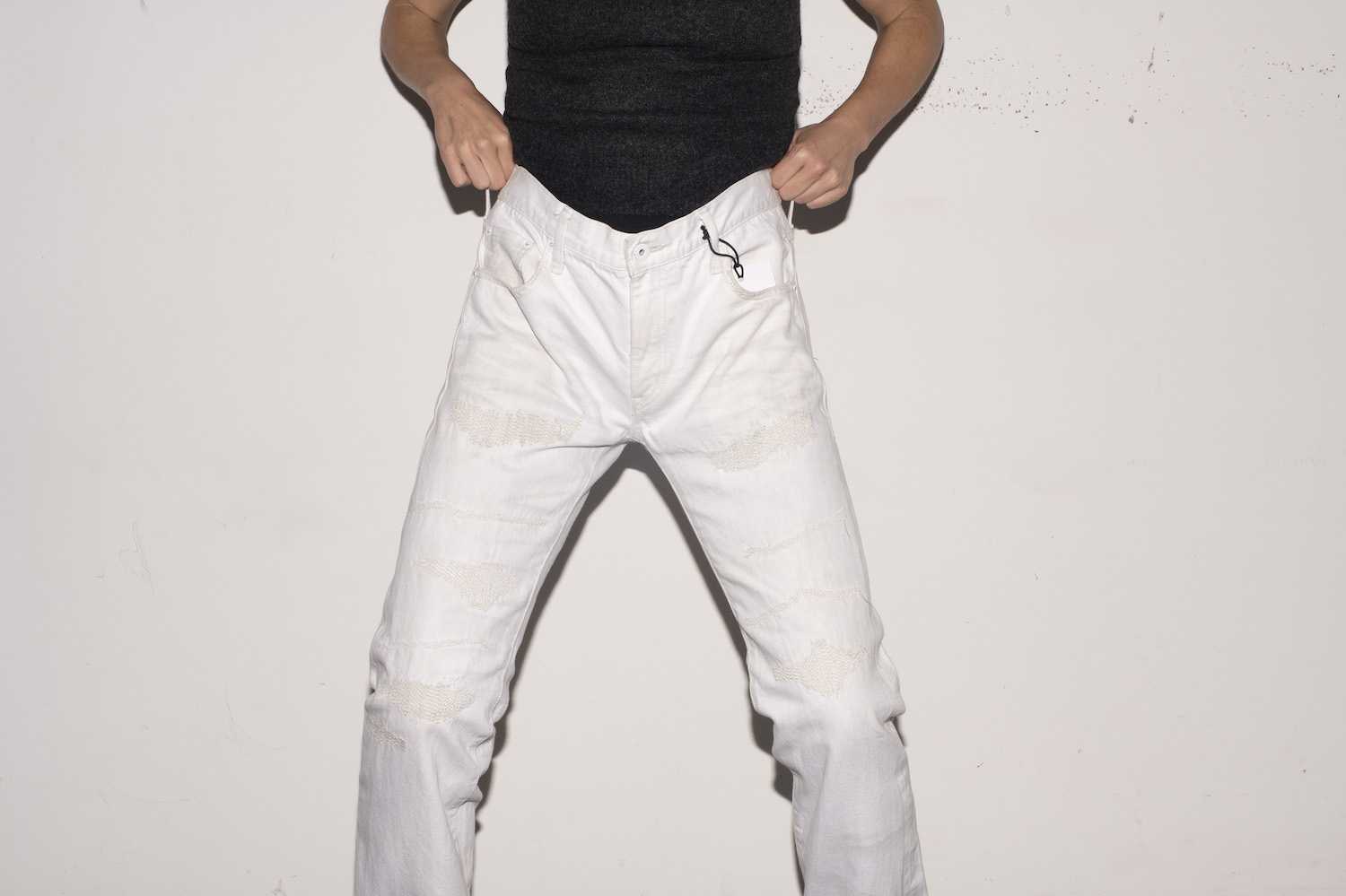

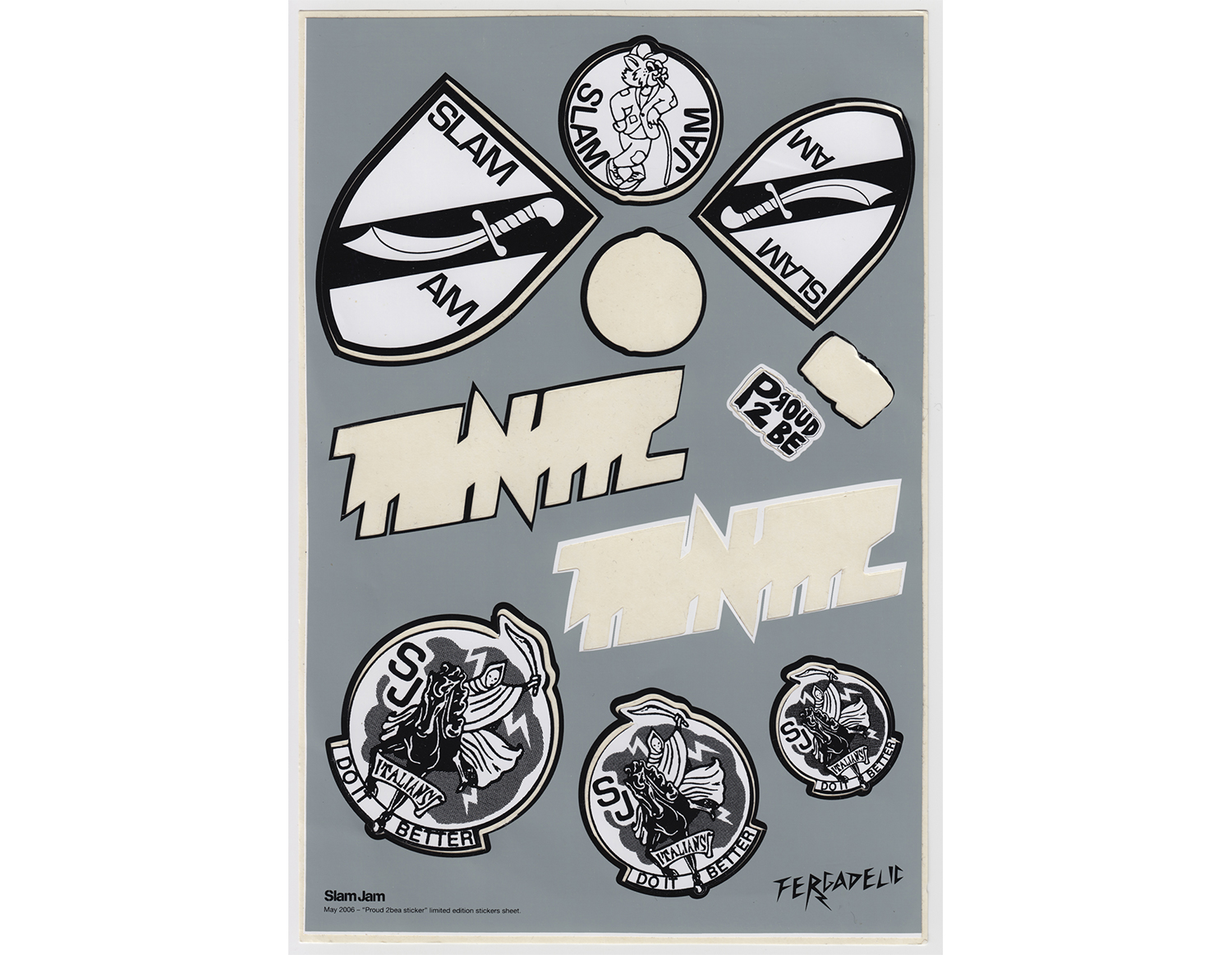

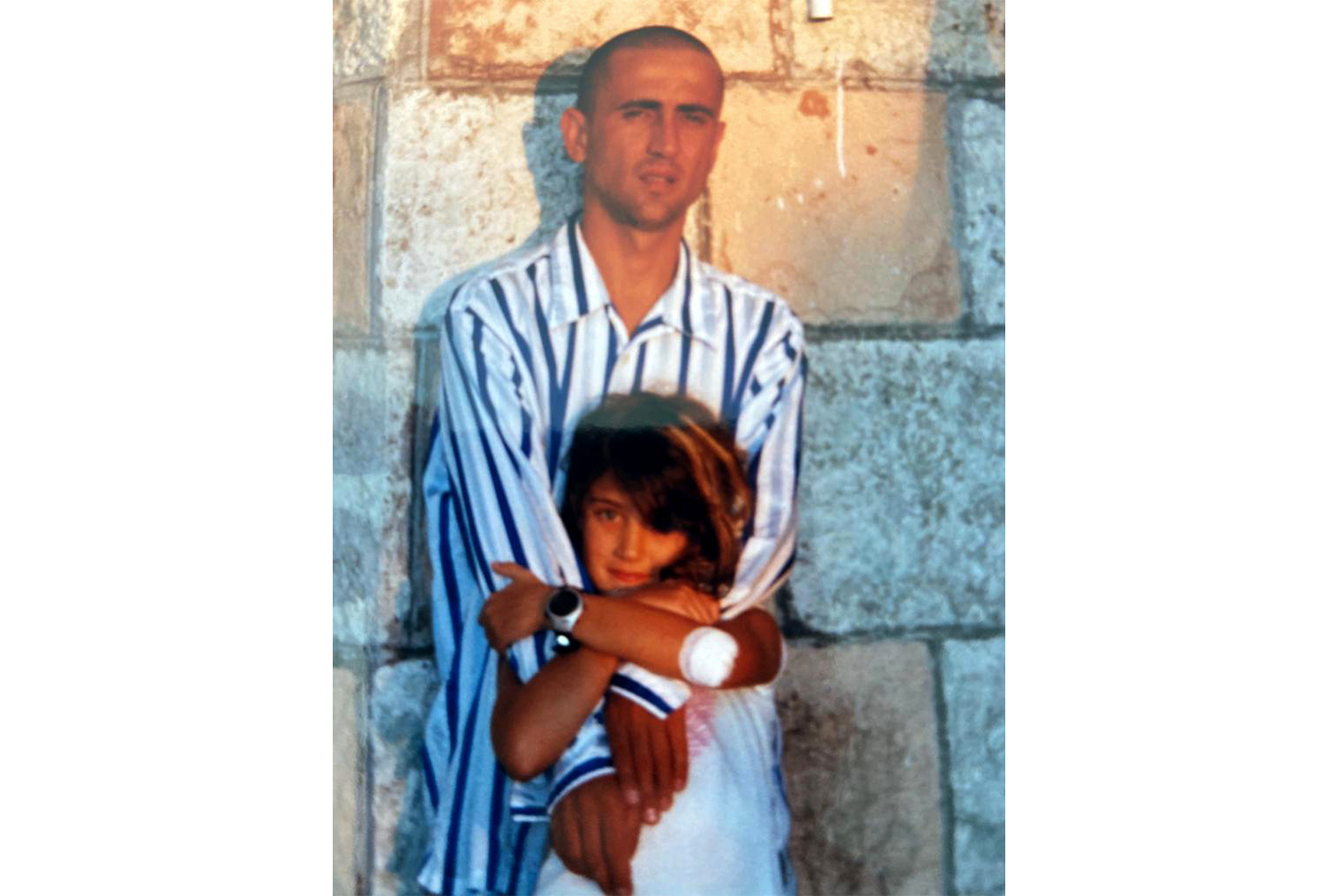

LB: Over the years I have purchased many clothes because I liked them and they excited me. Many of them I have worn and still wear today. When I was a kid, I would sell some to buy others. Over time I then began to collect them. Every day I would change several times, until dressing up became part of me, like a uniform that changes sporadically. A few years ago, my daughter gave me the idea of creating an archive, and after a year and a half of work we have come to sanction the beginning of this journey that tells the story of what Slam Jam has experienced and helped to address in some way.

GP: Slam Jam is not simply a “talent collector” but a movement; it is now a modus operandi. How do you think it’s translated by the younger generation?

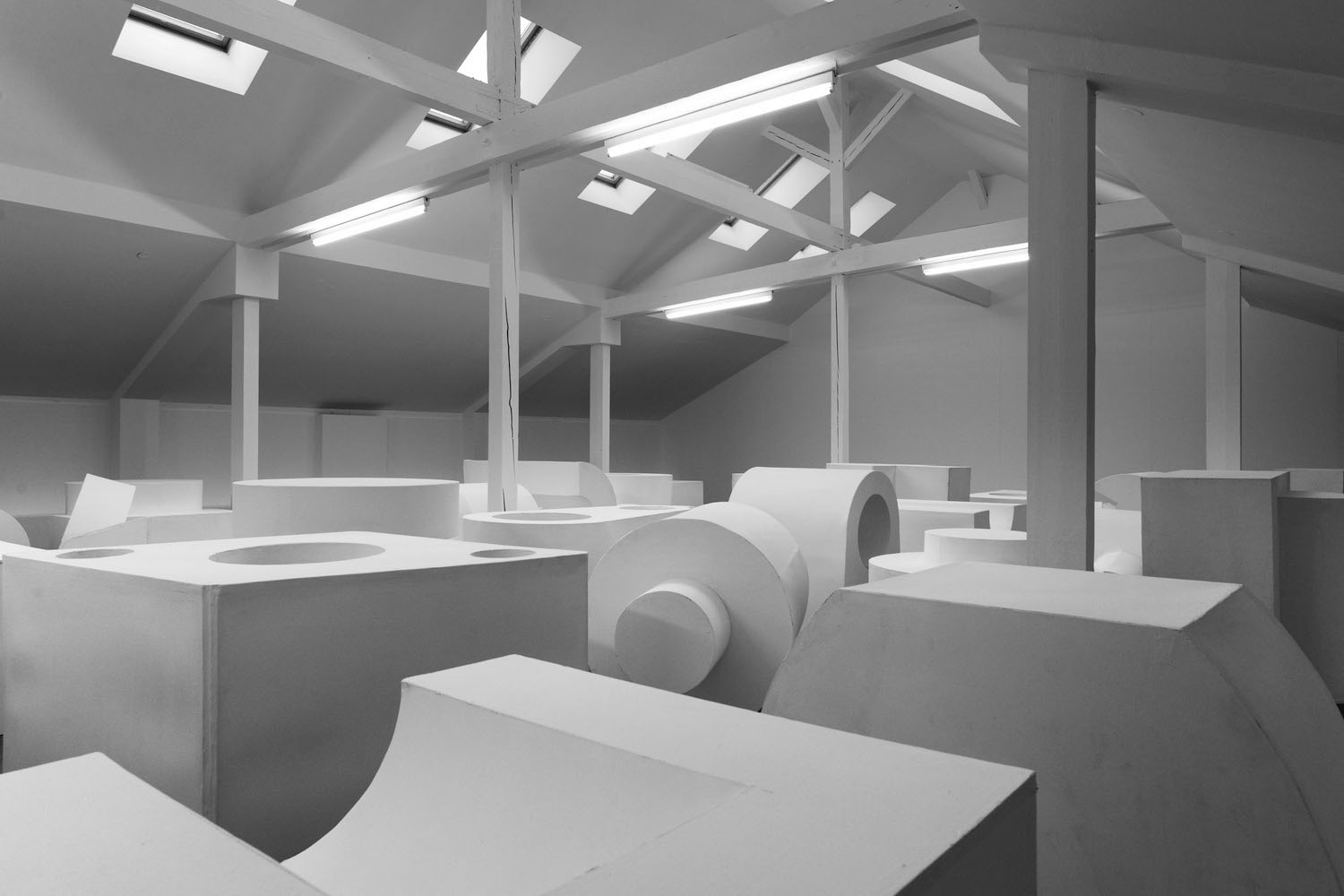

LB: Slam Jam has become a real platform, a multifaceted entity that is deciphered in various ways. The community is obviously wider than in the beginning, but also heterogeneous — which I am very pleased about. It is a greeting more than an awareness: Slam Jam wants to stimulate critical thinking in the newer generations, showing how the plurality of perspectives is a wealth to be preserved and contributed to. The archive demonstrates this. You see a series of garments that have been vehicles for very different messages, but that constitute a universe that we think should be looked at as a lens to decipher the world we live in.

GP: Why work on a digital-only archive and not also on a publishing project with Nationhood? Boris Groys argues that once launched into the “black hole” of the web, an archive loses its function and becomes everyone’s material. Aren’t you concerned about copyright issues?

LB: We developed the archive project out of an urgent dissemination need. We think that this is a very important asset both for me and for Slam Jam, and we believe it can be of relevance to other people as well. We felt it was almost a duty, a give-back to what we’ve called “community” so far. Regarding the copyright issue, considering that they are mostly objects, documents, and records bought by me, we did all the necessary evaluations and, in many cases, we involved the brands and the artists themselves — who are actually friends — in order to collaborate. We see this as a great opportunity to work together again. The fact that the archives can be used by everyone is, in my opinion, a positive aspect. The goal is to offer a narrative that broadens the cultural perimeter of those who access it. Today, having a more authoritative voice in terms of volume and range than in the past, this has become easier. Giving other forms to the archives, from publication to a vertical exhibition, is certainly part of the process. It is about streamlining a cultural heritage and disseminating it. It’s a very spontaneous need for sharing.

GP: Groys also speaks of “self-design” in reference to the individual creation of an image of our self in the age of social media. Do you think this aestheticization of the private has reached a point of no return, or will it continue indefinitely? How will it regenerate itself?

LB: In my opinion it will continue indefinitely and regenerate. For example, I couldn’t wait for town festivities or Christmas to get dressed up and go out. The important moments and places where I could show off what I bought were in the town square, at church, or at the club. Today the mechanism seems to be the same, even in digital contexts, and with much greater frequency. I think there will always be a regeneration.