“Public Art 2666” is a column that seeks to explore the interaction between the public domain and contemporary artistic practices, giving particular consideration to the resulting social impacts. The research is run by Collettivo 2666.

In spite of the success of the category of “public art” in recent art historical discourses, it is far from unanimous what the adjective “public” actually means when applied to art. It is not clear whether art acquires a distinctive public status because of its temporary unrolling within a certain kind of collectively accessible space, or if it is the artist’s intention to directly engage with the social texture to explain such constitutional publicity. Another question is the relation of public art to activism and the creation of new shared horizons of change…

Marinella Senatore established herself on the international scene thanks to the spectacular interdisciplinarity of her practice often flowing into events in the public sphere. Her work bears a strong participatory dimension, combining folklore with social critique via means spanning from text to installations and actions involving other artists and the public. In this interview, Senatore reflects on the concept of public art and the way it may apply to her own work, with a focus on some of her most successful projects and the recent collaboration with Dior in Apulia.

NG: How do you understand “public art”? Would you use it to describe your own practice?

MS: Public art is a very wide-ranging concept and I think it is very misunderstood nowadays. The very idea of “art and the public sphere” is applicable to a lot of artists from past generations. Among all the different descriptions: relational art, participatory art and community-based art projects also find a place under this label. Public art may even include temporary or permanent sculptures and installations in public areas. Under this light, it’s obvious that I am closer to public art rather than to traditional painting but it is rather the social sphere and stage that are important to me. My work is based on participation in a lot of senses. I work around the concept itself of participation: not only when I organise and activate projects for people to join but also when I conceive objects and artworks in my studio. I rethink and rewrite the idea of participation which doesn’t mean at all integration for me. It is something far more specific and interesting and doesn’t have much to with relational art historically conceived. I cannot deny that my practice is close to the field of public art, but I prefer to talk about the concept of participation in the social sphere. I think that this is more contemporary and says a lot about my real interests and focus.

NG: Does the concept emphasise any significant distinction with supposed “non-public” art? Maybe with reference to the market?

MS: It seems to me that things are today too sharply separated. There are artists whose practice directly engages with contemporary instances and activate confrontation with social issues, having an actual social impact. But we see this kind of work mostly in institutions such as biennials and documentas. It is hard to find it in auctions, galleries, private foundations or other kinds of institutions that are aimed at making different statements. This was possibly always this way but over the past few years it became increasingly sharp and – for me – unacceptable.

We still live a very conservative idea of what art and artists should do. We should consider art a job. Because this is my job. On the one hand, I see the market with blue chip artists and mainstream creations. On the other hand, practices with no budget at all. There are a lot of artists that cannot afford life with their work. Unpaid jobs and unpaid artists. This is a very important topic. Within the elitism of a very small circle of artworld people, artistic references are always the same. This is disappointing. I deeply disagree with a lot of things that I see in a system that yet allows also people like me to work. It is my system as well. In these times of pandemic, we are having a great occasion to rethink how to proceed in life and work, and how art could evolve and speak to people – a lot of people, not only to those who play in its field.

NG: Started in 2012, The School of Narrative Dance is among your best known participatory projects. It travelled around the world and involved thousands of people. How did it start?

MS: The School of Narrative Dance was founded in 2012 after a long experience with people and participatory projects around the world. At a certain point, I felt the need to create a sort of container for these experiences. The title itself suggests that narration and didactic experience are the core of the project. We try, every time, to involve local energies and activate local contributors as much as possible. I wanted to create the experience of an horizontal system of education and self-cultivation. Emancipation from the master, the Ignorant master in Jacques Ranciere’s sense. Of course I wanted something nomadic, that people could use beyond me. I am sure that this can happen, because I am providing tools for people to activate The School without me in the future.

NG: Is there a target, a specific slice of the public, it primarily talks to?

MS: It’s funny to reply to this question. We surely have a specific slice of public. It is the real public. People not necessarily connected with systems like culture and contemporary art. We are open to everybody. Our public is the real public: people that don’t care at all about the art system, people that move within it, people that don’t ignore what is art, people that never entered a museum or that visit them weekly… Everybody is welcome, no matter the skills and experience. Participants can then decide to either just join the workshop or make a final “restitution”: a performance in the public space. There is emancipation. Together with flexibility, this is the fortune of the methodology of the School.

NG: So performance is a big part of it…

MS: I am not a performance artist. I don’t perform at all. I don’t have anything to share with the seventies’ idea of performance. I don’t use my body, I don’t relate to the tradition of performance. I engage, encourage, foster, trigger, activate urban actions. They are always urban. It is important for both me and the people that they are so. Anyone can find in The School of Narrative Dance a safe place where to fail but also where to challenge themselves. That’s why people really like the School and we managed to engage with over 6 millions of people. The School is not just a container for performing arts. It is something far more interesting in my opinion because it is based on didactics and the development of an alternative system of education, where empowerment and emancipation are the main focus.

NG: What about dance?

MS: Dance comes at a very late stage. We share a lot of other different experiences before, and then we try to resolve them with the body. Dance should not be intended as athletic gesture but – just the opposite – as vernacular movement. The vocabulary and narration that everybody brings becomes the main focus of the work of our choreographers. It is the sublimation of the individual body and its coexistence with the others that makes the actions of the School so passionate and remarkable.

NG: Your work doesn’t only develop through itinerary and participatory projects. The series “Protest forms: memory and celebration” consists of works embedding mottos belonging to past revolutionary traditions. What’s your take on art and activism?

MS: I am an activist myself. Actually, I was an activist even before starting working professionally in the art field. Sometimes these two aspects of my life collided. Other times they developed apart. So, at a certain point of my career, I felt the need to address more activist instances with my work, bearing in mind the differences very clearly: an action as activist is not an artwork. The artwork, the formal information, the language of art doesn’t produce actions as activism can do, even though certain mainstream activisms like Pussy Riot or Even Black Lives Matters – with whom I worked – use languages borrowed from performing and visual arts. Activism is changing too, and I think that the binomial of art and activism is very contemporary, real and fruitful, but not always necessary or mandatory.

NG: Do you have any strong historical references? What sources did you use for this series?

MS: I was always interested in history – but history as told me by people. People that actually lived the experience of history. I am not intrigued by archives or research about political movements. Everything starts with people and from an emotional experience of history. Protest forms: memory and celebration departed from a reflection on the incredible impact of activism on art in New York since the seventies, to address equality and feminist issues that are very important to me. I am not a theorist or expert of Feminism but I know very well about equality and I clearly bear in mind what people ask for – and I breath and vibrate with them. Collective anxiety and sorrow is what I think I must address. That’s the main reason for the interest in mottos and words that I find through photos and pictures of riots, strikes or other manifestations in the streets. I take these sentences from people’s t-shirts or banners. Sometimes, researching a bit, you can find the roots of the mottos in older movements and protests. The legacy of the resistance in the street is pretty amazing. When people take the street is always an important political occasion. This is at the core of the series.

NG: Mottos are also at the centre of the Luminarie marking your recent collaboration with Dior in Apulia. Can you talk about your contribution to the project?

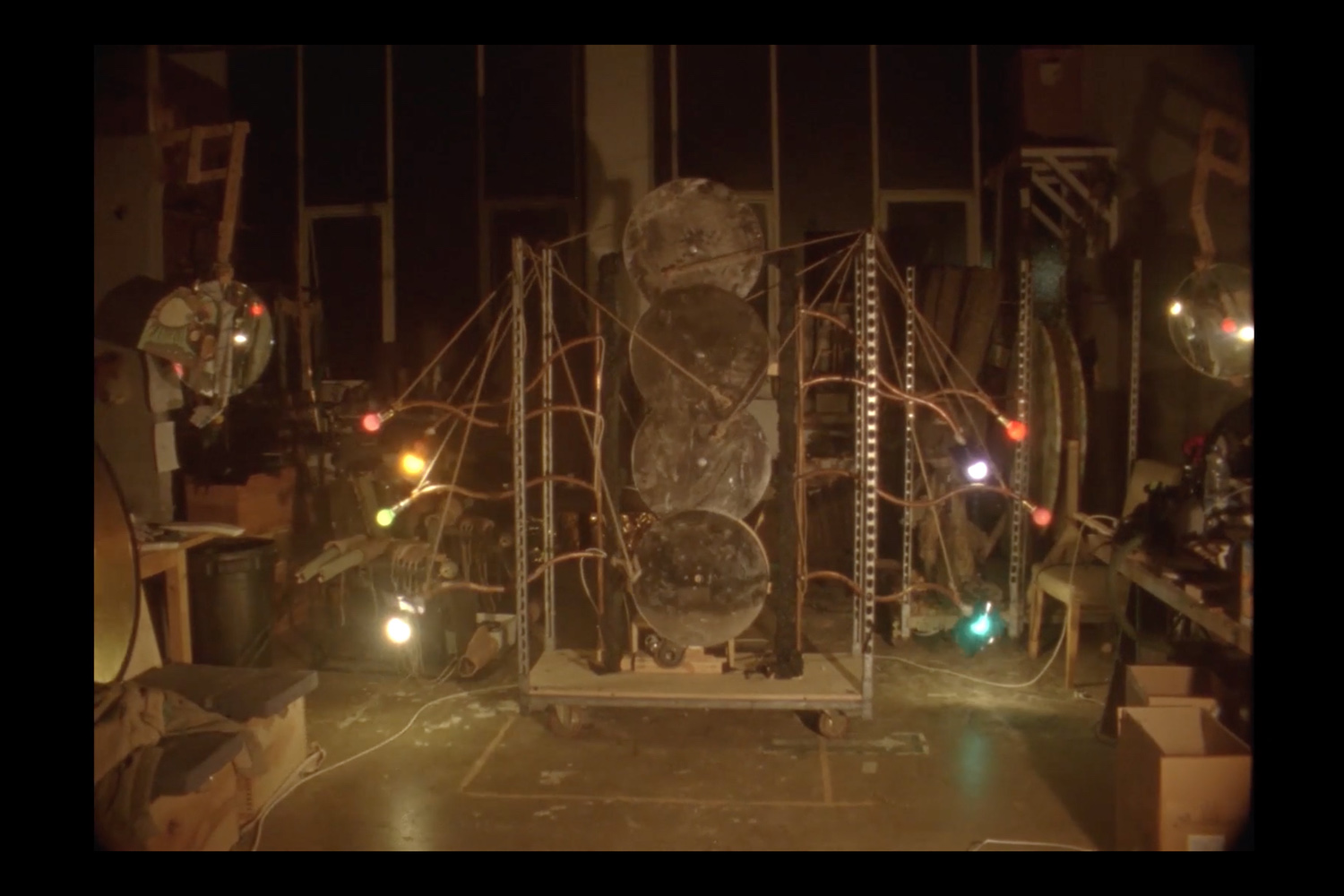

MS: The project in collaboration with Dior focused on the empowering and celebration of the Apulian community. Research on textiles, embroidery and fabric where at the core of this fashion season, and quite in line with my own practice. This is why I was invited for this specific project. My contribution was meant to be bigger, spreading through almost the entire city. Due to COVID restrictions we had to change and reshape it. So we incorporated a lot of things in the final show, trying to give an idea of the majesty of the Apulian heritage to the global audience. Having worked with Luminarie since 2017, it was almost obvious for me to hire craftsmen and small businesses that still produce hand-made Luminarie for local events, and then tailor them with sentences. Text is important in my work and I strongly believe that poetry can be a revolutionary tool for resistance. The different aesthetics of the neon signs and of the bulbs part of these traditional geometric decorations, this encounter of past and present and even possible futures, is fascinating. I think that mixing art with fashion, literature, music and cinema is very, very, fruitful. This contamination is important because we need to understand the public and what it demands. It is urgent to open the visual arts to the public rather than to the small circles of the big system made of rich families, auctions and collectors. This creates an exclusivity that is really the negation of what I believe art should be.

NG: It seems that the audience was particularly important to you…

MS: In this case it was so strong. Over 30 millions people around the world saw the show on streaming. So many people – for the very first time – could experience the Baroque of Lecce together with what a contemporary artist can do, plus dance, music and the creations of fashion designers. Every layer was incredibly overlapped and respectful of the others. I guess that it even worked as a vehicle to understand the power of an art installation without all the codes, information and preparation normally expected. Art is the first language that humans used, and its powerful in itself. Yet, the art-system creates a sort of barrier. The numbers that Cinema and Music have in terms of public are far away from art. We don’t even have the public of theatres. We are very exclusive. People think that this has nothing to do with them, which is an oxymoron: the absolute opposite of what should be. I think that this is extremely dangerous and urgent to address. So I realised that, nowadays, the more collaborations and contaminations I do, the better is for the art. The public is changing, the world is changing, so why art shouldn’t?

NG: How important is this kind of event in the Italian context?

MS: I think that it made a big difference to host this event in Italy – and in the South of Italy. Fashion designer Maria Grazia Chiuri strongly wanted it, and its was far more difficult than making something in L.A., New York, Paris or London. Especially in the South, as we do not have the same infrastructures to accommodate this kind of experiences. I think that the project empowered the people, the city and the South. It highlighted how big is the legacy and connection with our heritage – and how incredible it can be to reactivate it. I can just wish that this won’t be the only occasion, even though our country doesn’t invest much in contemporary art. Despite that, I think it was a game-changer experience.

NG: One of the quotes appearing in background was Christian Dior’s « On peut souvent créer des révolutions sans les avoir cherchées » [We can often create revolutions without looking for them]. What does it mean in the current political landscape?

MS: I liked this motto by Dior because I think that people – with their own lives – can really make the difference for others without really understanding how powerful their example can be. But this is something more poetic than strategical. EU is collapsing and the lack of unity and support was pretty clear during the most critical moment of the pandemic. I am not sure if the political vision really changed, and if the great limits of Europe’s unfair relations were or will really be addressed. The vision of politicians may not change – and possibly it won’t – but the daily life can be better. I strongly believe that the individual can make a difference in the community. That’s why I am fascinated by working with communities. In the safe zone described by the time and space of an art project – where there is no judgment or possibility to fail – people open up themselves and even raise conflicts, disagree, hate but also manage to understand each other. This experience of collectiveness without exclusion of individuality is transformative. I have worked in almost every continent with over 6 millions people, and I got the feeling that they really get transformed by the experience. Sharing an artistic experience can truly make a difference, change minds, create bonds and destroy barriers.

NG: This is beautiful, but utopian?

MS: My utopia is tested. I saw this happening. I am of course conscious that mine are just art projects, temporary experiences, which is how I think experiences should be. Especially in the social sphere we cannot be abusive. I experienced the creation of alternative ideas of community, stepping beyond divisions of race, age, status and financial resources. If this is possible in just two months of a participatory project, how powerful could it be to have a lot of these experiences – not only related to art – in society? If I witnessed with my own eyes that this can happen, why should I think that the revolution cannot be done?