“The Uncanny Valley” is Flash Art’s new digital column offering a window on the developing field of artificial intelligence and its relationship to contemporary art.

When artists ask an AI to build an entire digital world, implicit is the demand that it be appreciable to a human public. In the process, the AI discards variables that are unsuitable — elements that won’t be detectable to human senses or that don’t fulfill the narrative demands of its makers. Landscapes generated by AI are thus affected by the requirement for public enjoyment and cannot entirely recapture nature’s unpredictability.

The aspiration to design landscapes, indeed whole worlds, that not only appear natural but rather surpass the wild in beauty, was crystallized in the eighteenth-century English landscape garden. Architects designed vistas comprising informal compositions of trees, bushes, and flowers that weren’t so obviously artificial as those found in the contemporary palaces in France and Italy. Instead, they sought to present an idealized vision that accounted for nature’s willful asymmetries. The planning of the jardin à l’anglaise was thus informed by the concept of the picturesque as formulated by English artist-cleric William Gilpin in his Essay on Prints of 1768. His vision of picturesque beauty as “that kind which is agreeable in a picture” therefore shaped the understanding and aesthetic enjoyment of all landscape, whether natural or not. In the words of Francis Klingender, “If Burke’s ‘beautiful’ is neat and smooth, Gilpin’s ‘picturesque’ is rough and rugged.”

Garden architects incorporated artificial lakes, fabricated ruins, and fairytale bridges in order to conjure an idyllic pastoral experience. Landscape architects such as Capability Brown (1716–1783) imposed order on nature in a subtle but tangible way through strategically positioned woods and carefully juxtaposed flora that catered to human visual experience and perambulation. Two paradigmatic English landscape gardens — Brown’s Stowe and William Kent’s (1685–1748) work at Rousham — are appropriately artificial simulations of the kind of Arcadia Poussin had once envisioned (whose canonical Landscape with the Funeral of Phocion, 1648, constructed an imaginary Athens based on the artist’s experience of Rome). These gardens served the purpose of being both beautiful and enjoyable — spaces in which natural growth might be artificially experienced. They also reinforce the beauty of AI-generated worlds now, which externalize contemporary aspirations for artificial augmentation.

Sublime Worlds

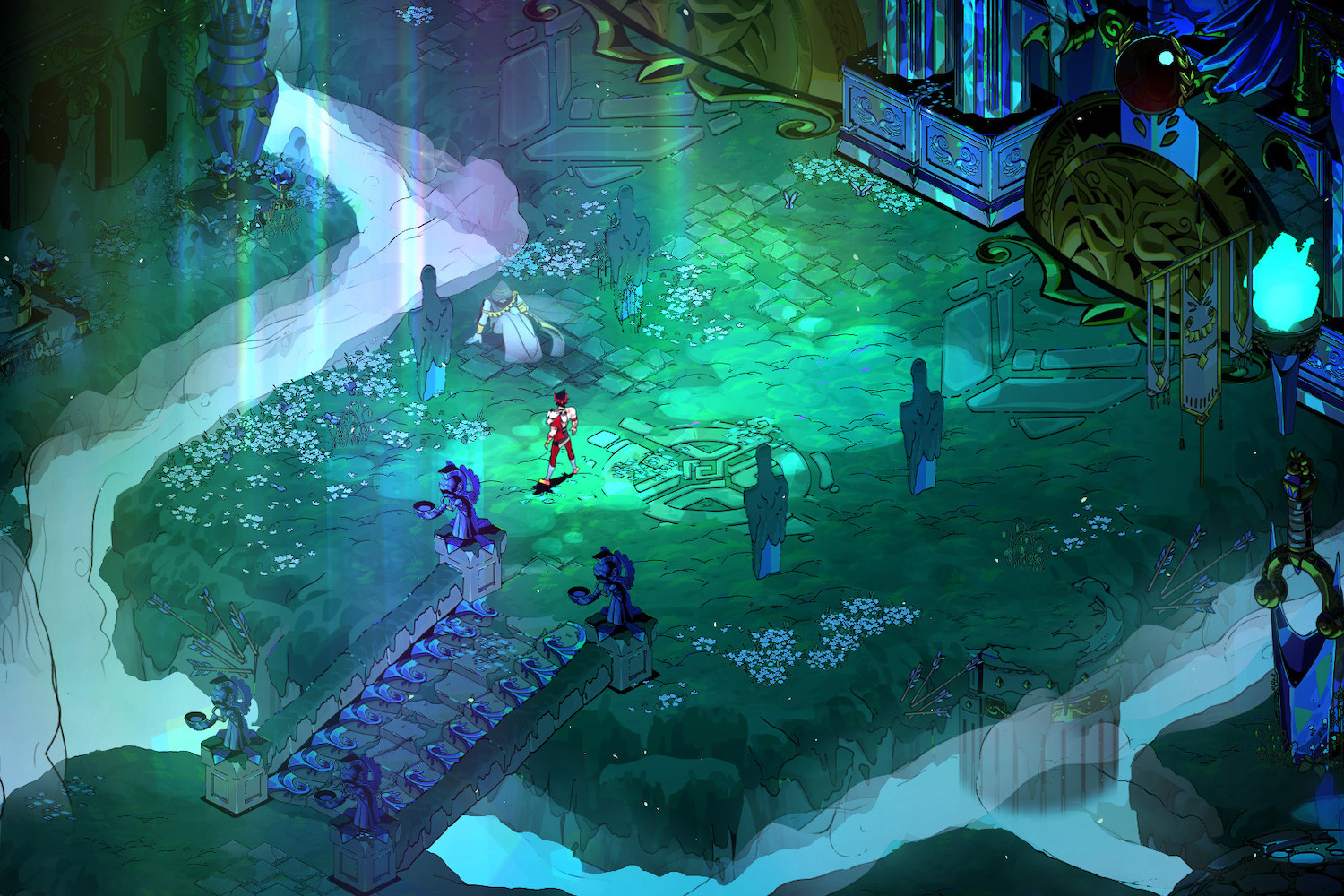

In video-game production, there are normally two ways to create digital worlds. One can design the map by choosing the location of each component: city, tree, or NPC (“non-player character”) that a player will encounter while inhabiting the digital enclosure. Alternatively, one can develop an algorithm according to certain parameters and let the software generate the environment. One of the earliest examples is Rogue (1980), a prototypical dungeon crawler developed by Michael Toy, Glenn Wichman, and Ken Arnold in which the player navigates a character through a labyrinthine environment, fending off monsters and collecting treasures along the way. What made Rogue unique when it was released was that every level and terrifying encounter was procedurally generated on every playthrough, with each experience distinct from the last. It also instituted a new game mechanic known as “permadeath,” whereby player characters who lose all of their health are no longer operational, with the result that players must restart from scratch. Even today, such innovations continue to inspire new so-called “roguelike” variations: from Spelunky (2008) and The Binding of Isaac (2011) to Hades (2018/2020) most recently. Following Burke and Kant’s attempts to theorize the sublime, the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) captured the fear-pleasure paradox of sublime experience, beyond the limits of reason:

Many objects of our intuition arouse the impression of the sublime by reducing us to nothingness in the face of their spatial magnitude or their advanced age, i.e. their temporal duration, and yet we revel in the pleasure of seeing them: very high mountains, the pyramids of Egypt, colossal ruins of early antiquity are all of this type.

– The World as Will and Representation, 1819.

It was Rogue’s conjoining of creativity — that of exploring ceaselessly new worlds — with the risk of their being swept into oblivion at any moment, that rendered a genuinely new vision of sublime experience. In its wake, Elite (1984), a video game set in deep space, was initially planned to include a total of 282 trillion procedurally generated galaxies encompassing more than 250 solar systems for each. However, the publishers worried that players would be daunted by its scale and the potential consequences of failure; ultimately only eight such galaxies were incorporated into the final version. The institution of permadeath nonetheless ensured that a new generation of video games were underpinned by terror (Burke’s “ruling principle” of the sublime) — that the digital world depended on the player’s survival.

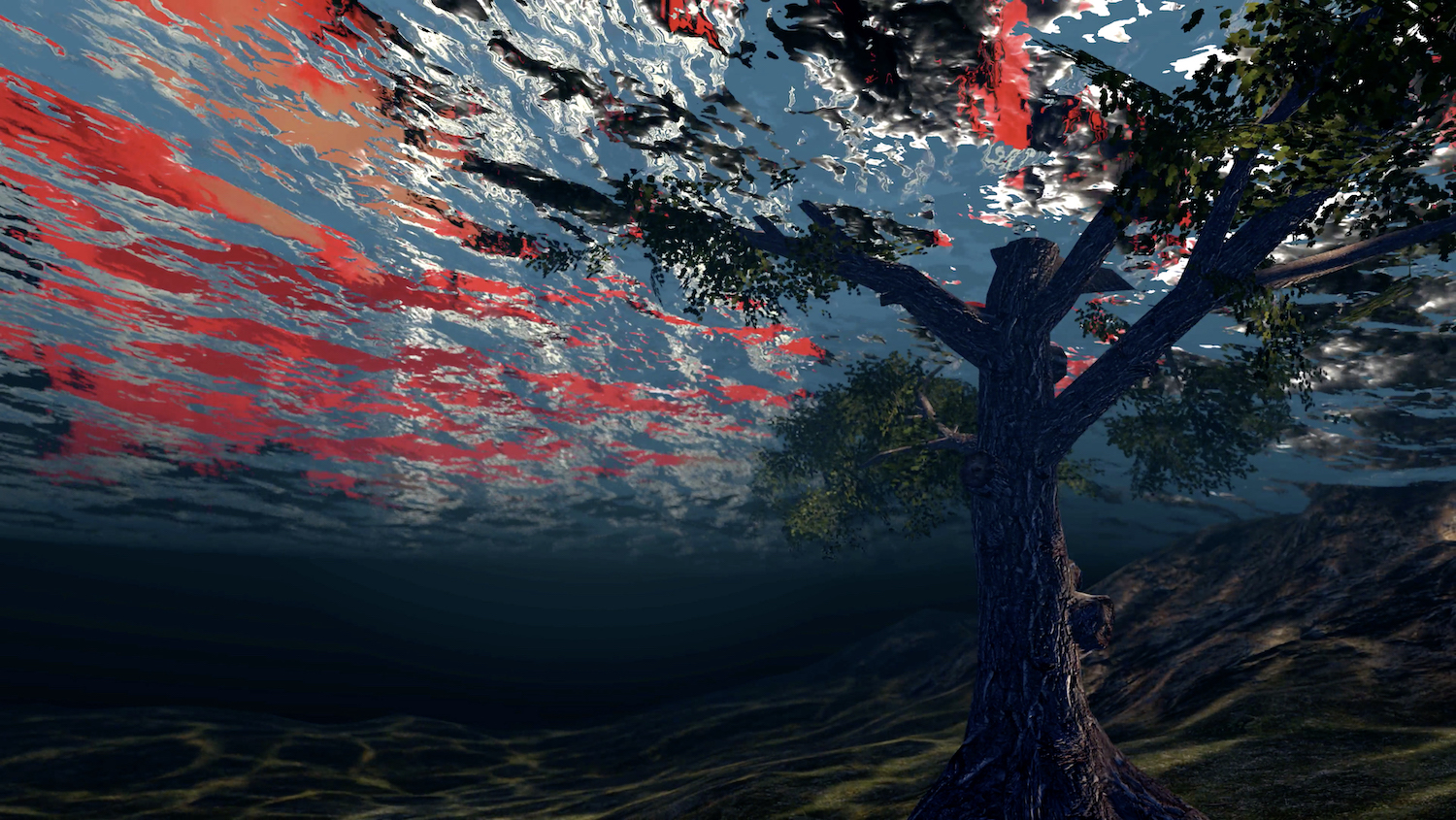

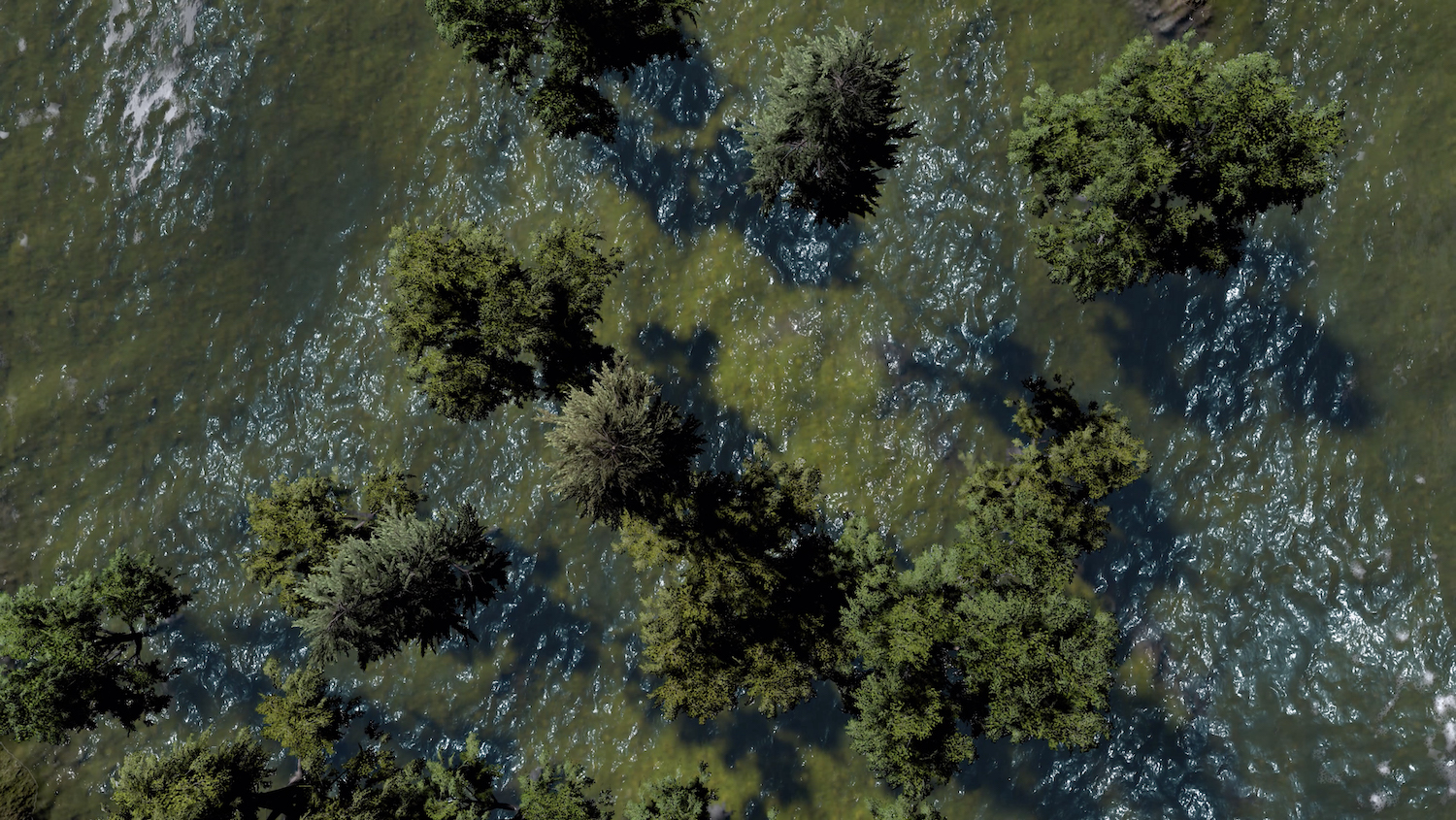

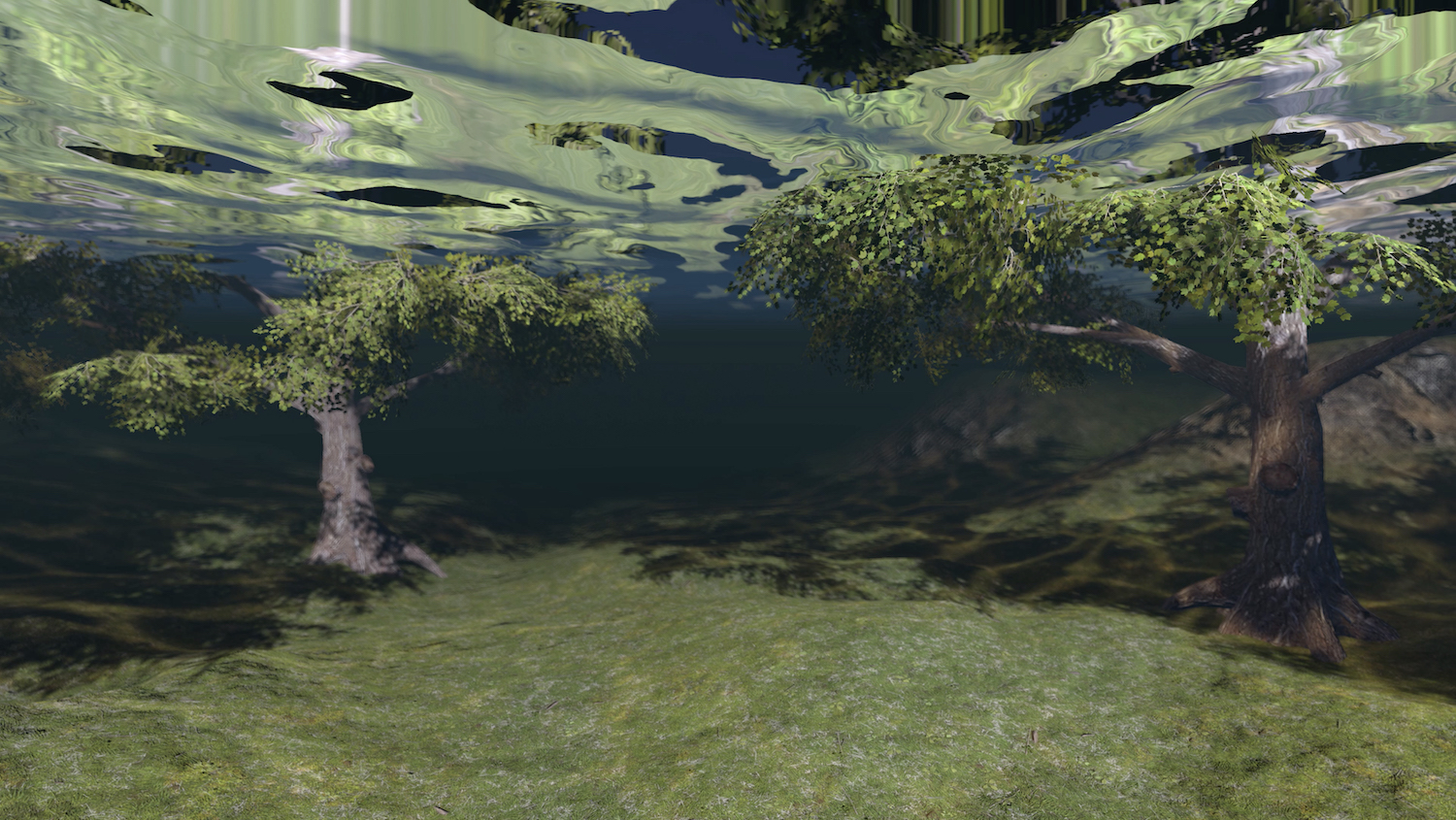

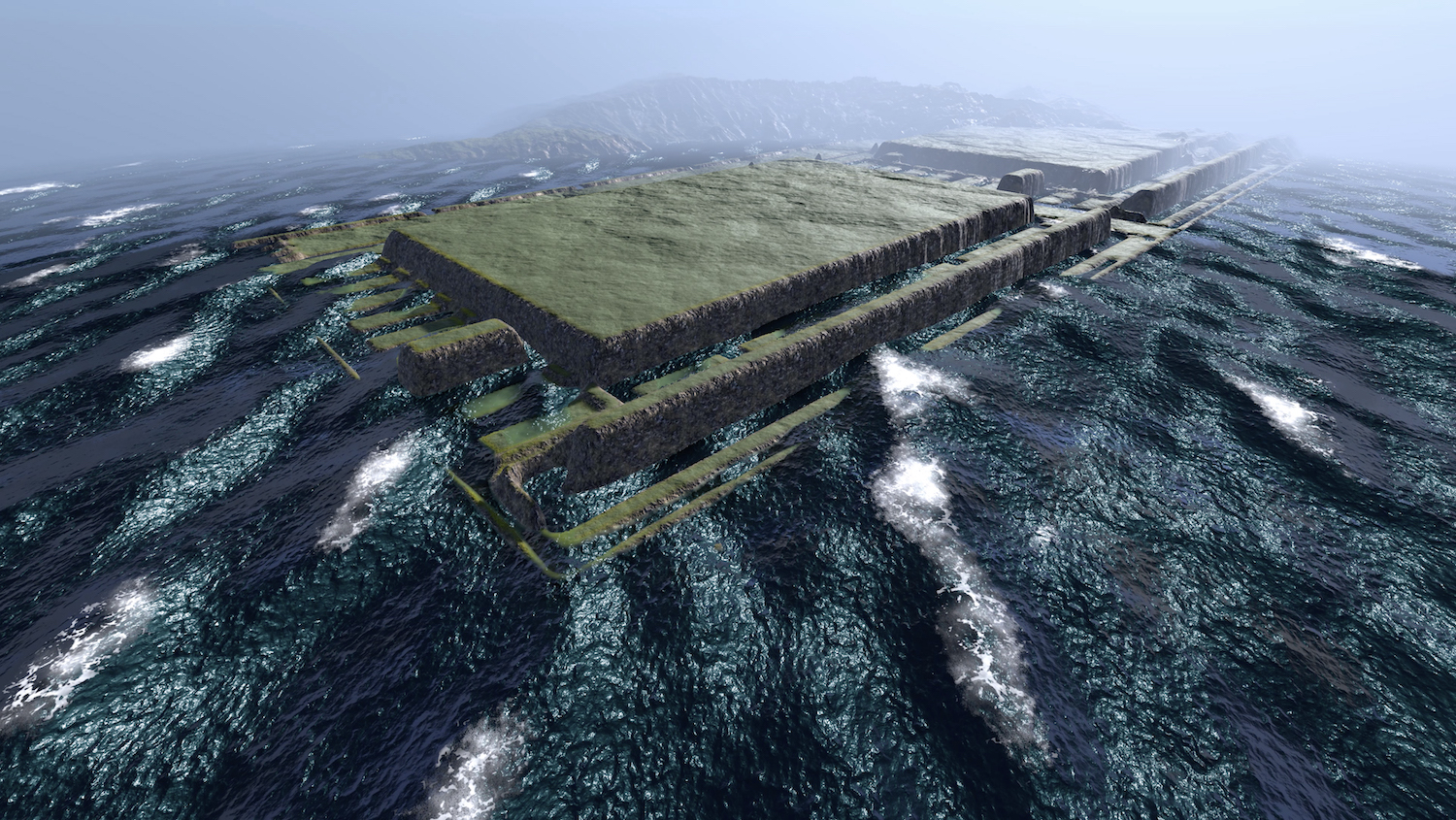

Artist Jan Robert Leegte (b. 1973) has recently explored the overwhelming nature of AI-generated worlds with Performing a Landscape (2020), a live installation comprising a storm-soaked landscape generated in front of the eyes of the public. Screens and projections offer a fragmented experience of the virtual landscape, leaving the viewer terrorized and disorientated by apparently preternatural forces. The spectator’s perspective is that of one submerged underwater, “safe” from the ensuing cataclysm overhead.

To view the work in situ is to experience an artist’s rendering of digital landscape mediated by romanticism for a pre-internet past — a conflicted scene, torn apart by unseen winds, populated by ruins — a scene perfectly suited to a nineteenth-century picture gallery.

Leegte’s installation puts the viewer in the shoes of the angel of history as expressed in Paul Klee’s (1879–1940) Angelus Novus (1920). Famously described by Walter Benjamin (1892–1940), the angel — facing into the past — can only experience the accumulated consequences of catastrophe while being dragged into the future.

The fine line between awe at natural forces and terror of dystopian technology has also been investigated by artist Leslie Nooteboom. Inspired by the obstruction of natural light in the urban metropolis, his AI installation Komorebi (2017) comprises a robotic arm attached to a projector that generates light and shadows in a way designed to simulate the effects of natural light in a domestic interior. It thus incorporates random movements as well as the indexical trace of aqueous surfaces, trees, and other elements experienced as mediated nature. By recreating the sunlight entering through a non-existent window, the work resonates both romantically and uncannily, calling to mind sci-fi narratives of humans confined to claustrophobic environments, whose only solace is a notional outside world. Nooteboom’s AI-generated environment registers in an understated way, without undermining its technical achievement. The viewer appreciates the effects of a simulated world instead of the thing itself. Like defying Medusa’s terrifying gaze with a mirror, we experience the reflection of a simulation that would otherwise defeat us with paralyzing force.

Beautiful Blueprints

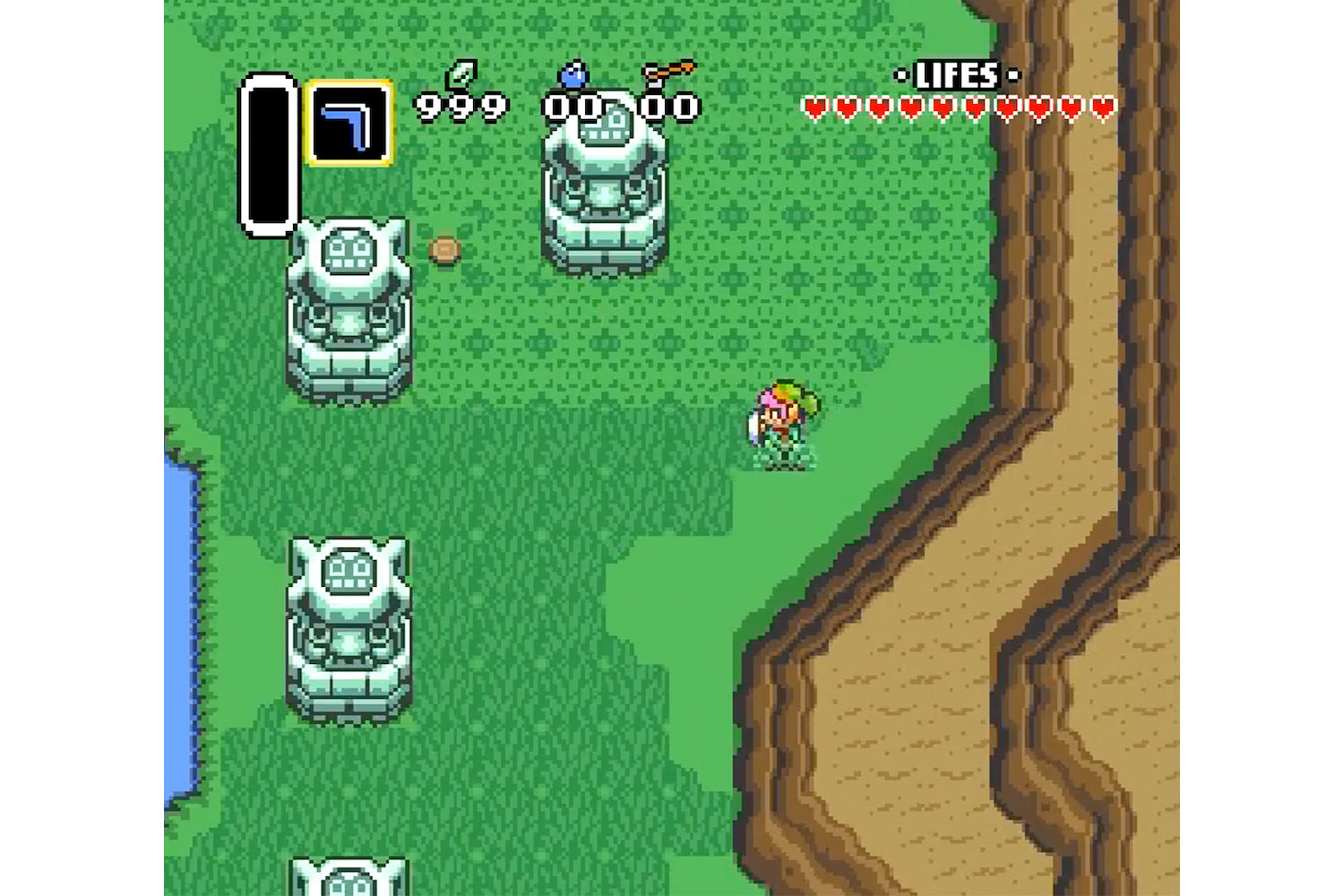

When interacting with a computer-generated world, we accept that the landscape we inhabit is shaped by the decisions of others: a mountain is placed in a specific location because it serves a purpose, either visual or ludic. As a player, one has the feeling of operating within someone else’s dream wherein one’s actions are limited by the developers’ script: enter this town, talk to that character, collect these treasures. Back in 2013, Emilie Brout & Maxime Marion called attention to the rule-based nature of virtual worlds in their work Cutting Grass: a self-contained simulation of infinite duration in which the titular character, Link, of the video game Zelda: A Link to the Past (1991) is shown perpetually cutting grass, uncovering rubies, and acting out the behavioral tropes inscribed by his virtual universe. Although the ruby counter has long since reached its limit, the character perseveres regardless, even now. In the process, the developers reduce currency accumulation to the level of the absurd, with the protagonist rendered a pastiche of Camus’s Sisyphus — who finds happiness in repetitive labor rather than any wider meaning.

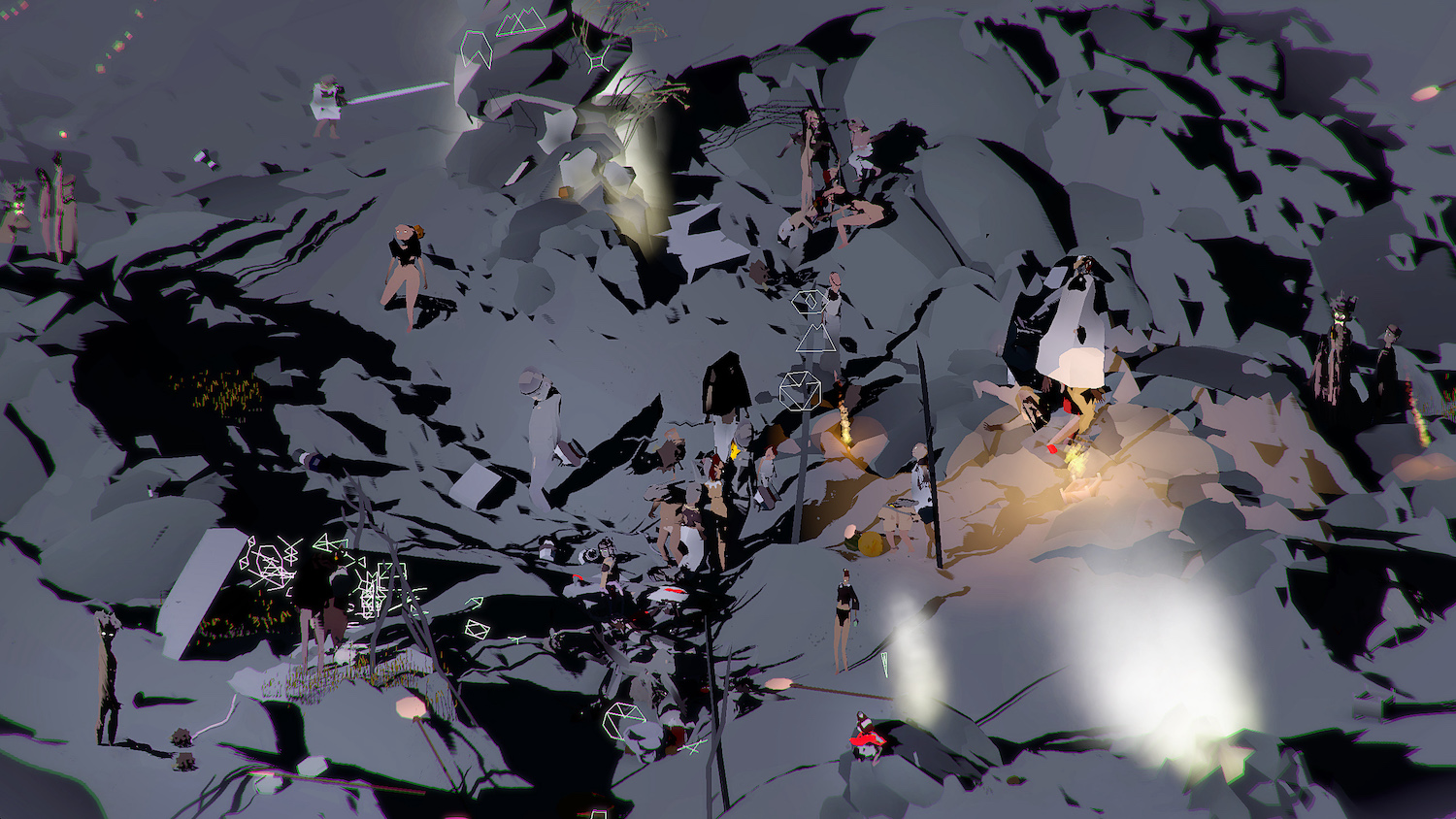

While busying herself with the gameplay loop envisioned by the developers, the player of an AI-generated world may observe such patterns as a recurring cluster of rocks or the newly spawned environment of the next level up. Only when a player becomes aware of the strictures of a rule-bound structure does she begin to see beyond the façade of the digital Potemkin village and to appreciate the virtual environment as the product of human creativity by virtue of its difference from the real world. In his “Emissaries” trilogy (2015–17), Ian Cheng investigated the potential of ceding authorial control through live, autonomous, and self-sustaining ecosystems created using a game engine. In these environments, characters and wildlife interact independently of one other, guided by the disguised direction of their maker. What makes Cheng’s work invariably so compelling is not the limited series of actions and combinations that each element is trained to perform, but rather the active cultivation of a newly entropic nature. Cheng’s virtual worlds highlight simultaneously the grandeur of their design as well as the ultimate futility of imposing artificial boundaries.

In The World as Will and Representation (1818), Schopenhauer determined that the enjoyment of the idea underlying the object reflected the truest feeling for the beautiful, that one must enter into a state of pure contemplation to achieve aesthetic pleasure, wherein “we are raised for the moment above all willing, above all desires and cares; we are, so to speak, rid of ourselves.” AI-generated worlds may have been produced to serve a ludic purpose — to fulfill in-game objectives. But they exist independently as art forms, as creations of a human mind. When one ceases interacting with a virtual world on its terms, to enjoy it as another product of human creativity, every component — whether a tree, NPC, or sublime sky — carries with it the mark of the maker’s invention and skill.

To understand the grammar underlying the appearance of AI-generated landscapes is to understand one’s own mediated experience of the world today. For the video game artist, the algorithm has become a means of simulating the secret rules that regulate nature, from the blooming of a flower to the terror of a black hole in deep space. It is a privileged glimpse of an inevitable, sublime catastrophe.