Lightly saturating Peter Kilchmann’s Zurich gallery with color-blocked walls, wallpapers, and framed images of varied sizes and types, Shirana Shahbazi’s recent exhibition continues her involvement with the familiar modernist concern (in art and life) regarding the legitimacy of the photographic. The exhibition’s title, “Reality Show,” is the sort of splintered truth costuming as pun that Shahbazi’s photographic practice is rooted in. It speaks to the ways in which her installations attitudinize as colorful visual entertainment as a whole, while encasing serious concerns and consummate visual rhythms in their individual parts.

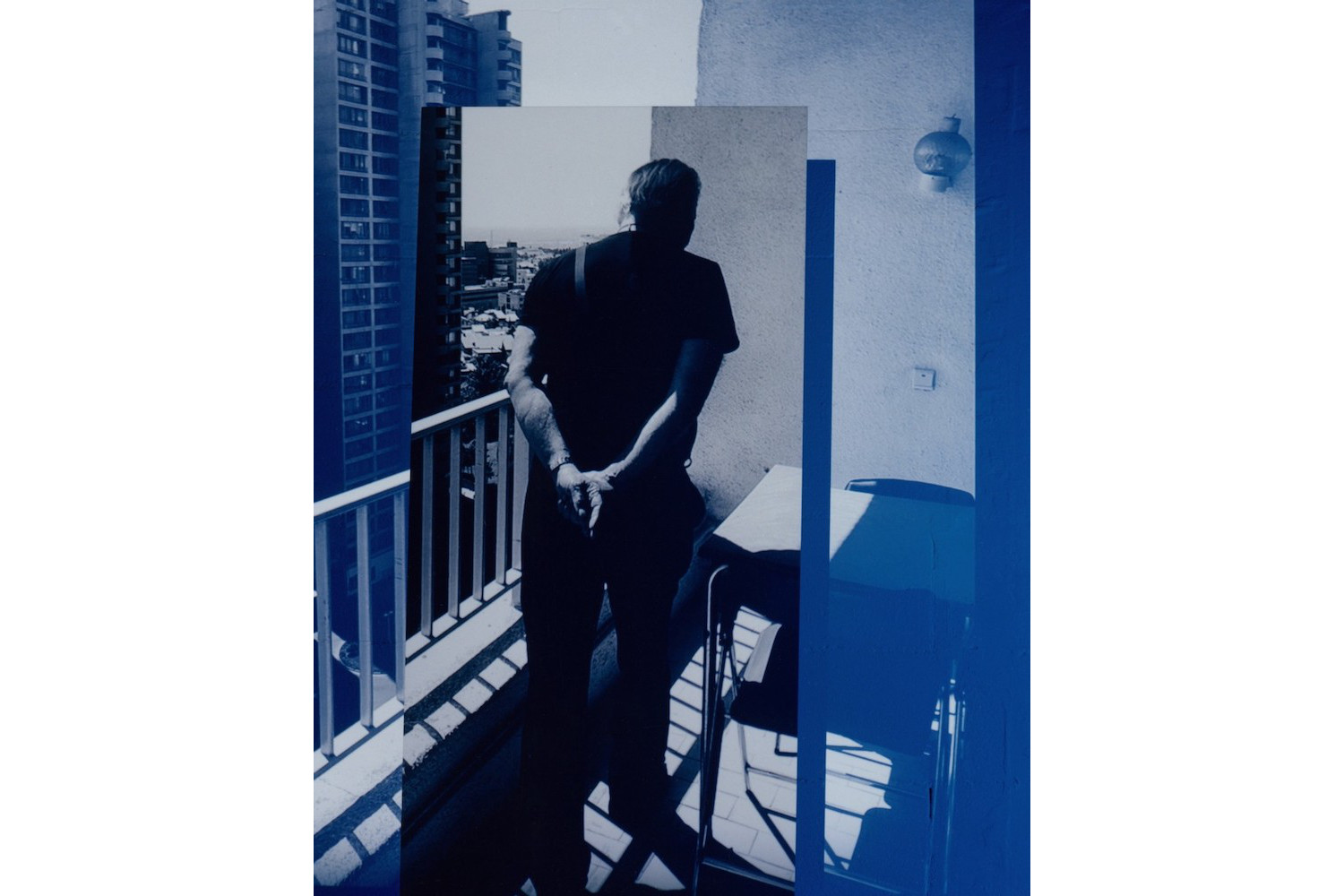

I’ve always read the wall paintings and wallpapers that form the installations Shahbazi has situated her works in over the past decade as elements of expansion: her photographic oeuvre leaving its contained frame and venturing outward into the viewer’s and exhibition’s lived world. Perhaps recent experience supports an opposite reading as well, as the idea of closed gallery rooms and overlaps finds echoes of containment in many of the works.

One of four blanket-size photographs (all works Untitled and from 2020) appears to depict light cascading across a tiled floor, exposed multiple times and shifted so that overlaps of yellows and blues create a coordinated and merged composition of blocks and outlines. A receding image seems to materialize as a cinderblock wall. The depth to which the eye wishes to wander is impossible. This work is hung against a large rectangular grayscale wallpaper of similar but more recognizable overlays. A domestic interior, a studio interior, an urban block.

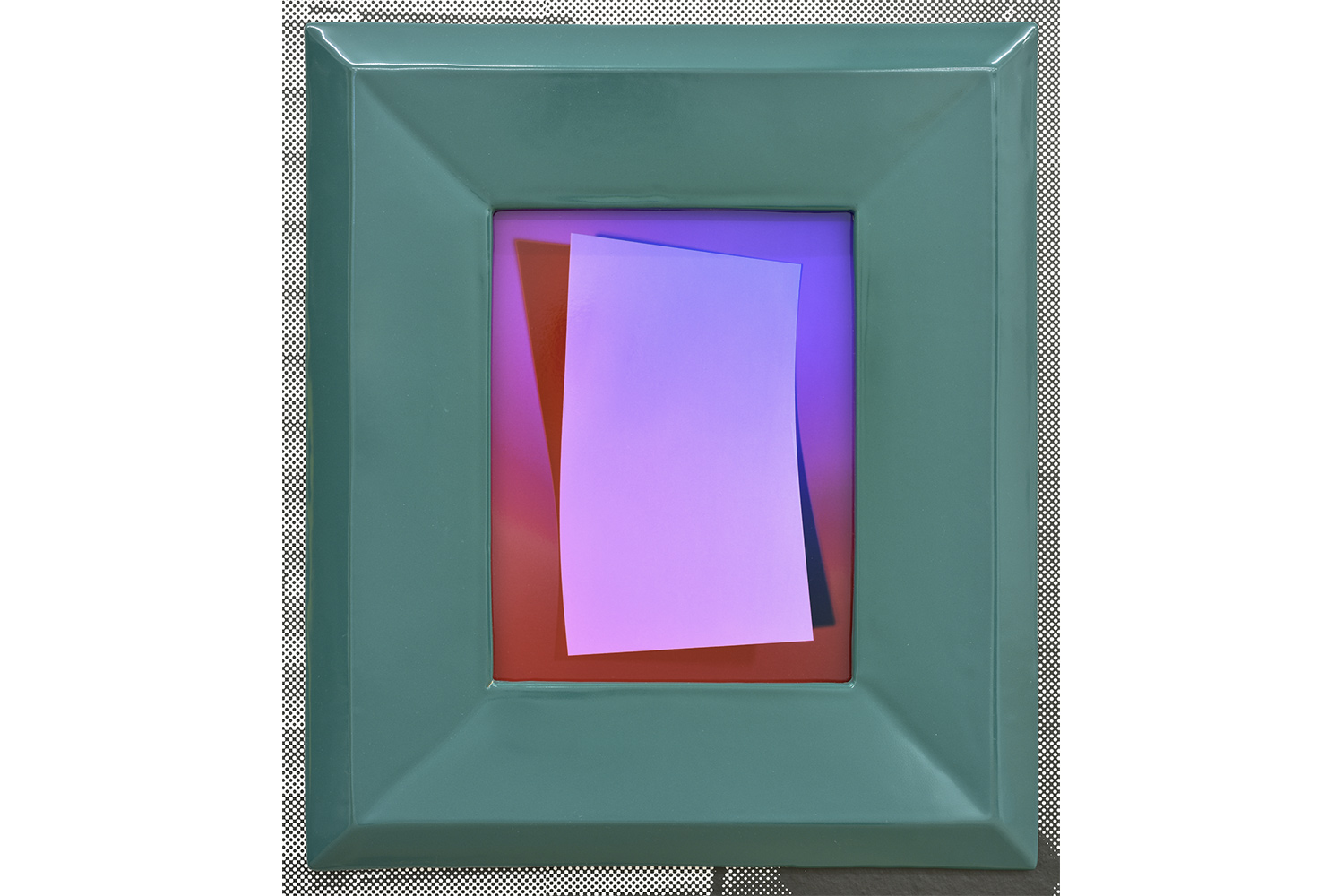

Elsewhere small single-subject photographs in almost garish intensity are framed in wide handmade ceramic frames in paler tones. A vividly pink floral vase in a rose frame, say. Hung against similar wallpapers, or walls with large blocks of color, they are somewhat in opposition to the larger overlays yet echo their themes of constraint.

Shahbazi’s analogue manipulations, like photograms, rocket her static subjects to a timeless now. Her work has often dealt with the impact of moving globally between cultures of home, life, and labor. This new work, made during a time of difficult physical navigation, suggests that even what one views within the studio or home is captured at a remove. Perhaps not from the outside in, but closer to an inside looking out. Like the photographic experiments of the Russian avant-garde, Shahbazi’s work also has a utopian bend rooted in the now. Any concept of a future or past is placed at our feet in the present — wherever and however abstracted, unstable, and immobile it may be.