K8 Hardy takes medium specificity to the max in “A New Painting”, an exhibition that promises and indeed comprises a singular work on something like canvas: March (2020). But Hardy, an artist of broad ability and humor, has never done one thing at a time and is not about to start. Naturally, this painting is one that does the work of a dozen.

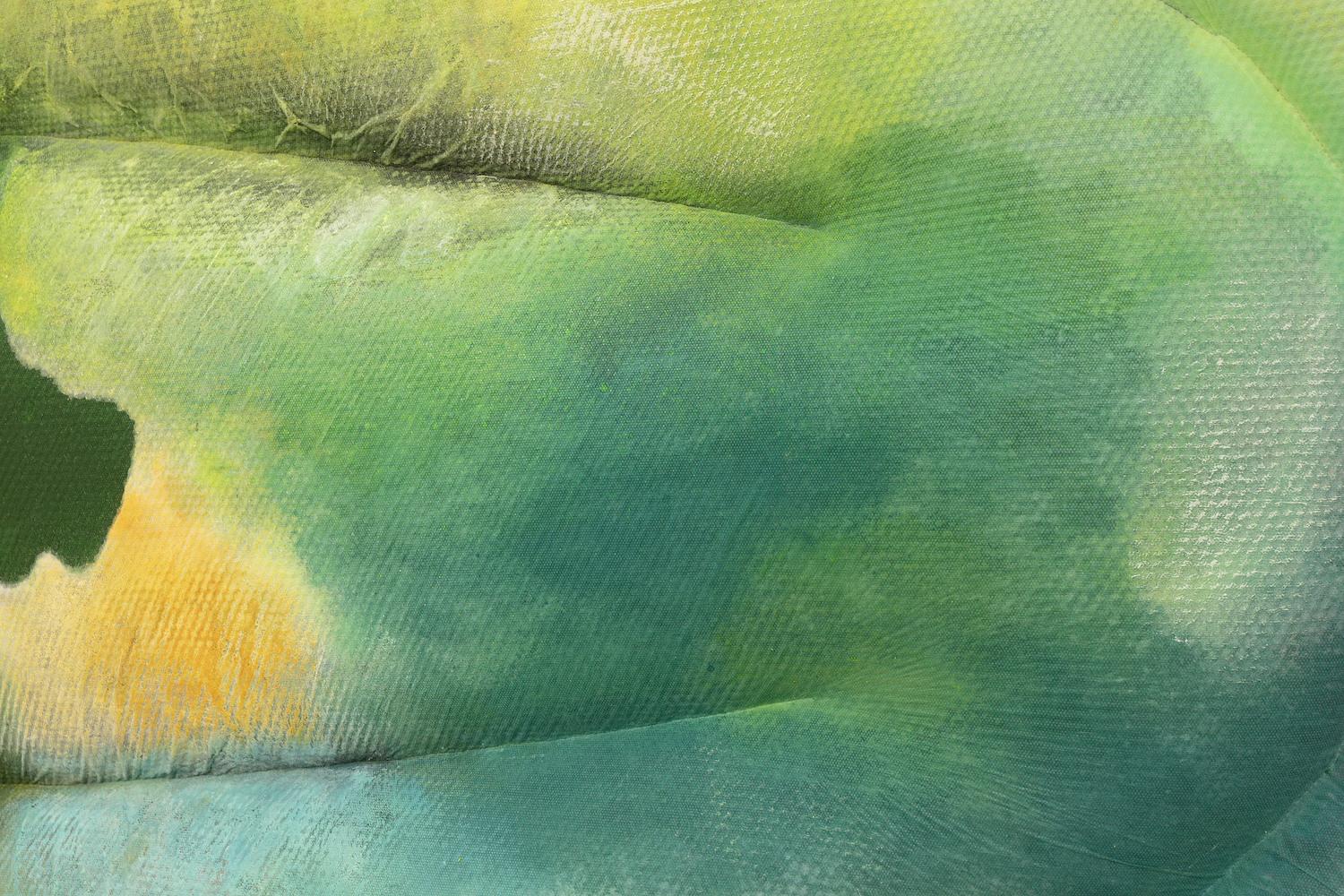

In preparation for March, Hardy made nearly thirty studies on paper and fabric, working with gravity as her studio assistant to perfect her mistakes. Beset by color, hands tie-dyed—she must have looked like a feminist Helen Frankenthaler. Stain being an anagram of ‘insta,’ the irony has never been richer. Hardy’s colors are redolent of a delicate and frankly imperiled world. Her palette is alien, alchemical, chemical. Yellow like Gatorade. Grass green, bluing to fungal. A kind of neon peach. And in the center, a shade so dark it absorbs all the others. Jules Olitski: “My pictures are only colors sprayed into the air and suspended there.”

If March were only colors it would be beautiful, but it is also a shape. The Greenbergians sought to turn ground into air, so that figure, form, and ground were indivisible. Hardy skews this consummation. Her ground is in a sense a figure—it is a fabrication based upon a recognizable, banal object which happens to be white and clean and tightly woven. And in fact the figure swallows up the content, forcing paint to take its shape, as opposed to the way Frankenthaler, Olitski et al turned fabric into another part of paint. We are reminded of Claes Oldenburg’s early soft sculptures, in which unmentionable objects are blown up to statement size. His reaction to the flatness, what he saw as the boringness of AbEx. But as a sculpture, March would be very flat, whereas as a painting, it’s hyperbolic. The particular shape of the ‘canvas,’ as well as its many absorbent layers, reinforce its status as less surface, perhaps, than receptacle. Frank Stella: “A sculpture is just a painting cut out and stood up somewhere.” Hardy’s painting is sculptural to the degree that, say, Jackson Pollock’s Cut-Out (1948—1950) is a sculpture, but it is also thoroughly laid down and it is even more wall-bound than a canvas, since its softness makes it impossible to casually lean.

You could hang it on a ceiling, though. Something about the way the paint is applied makes the viewers—us—feel like we’re the ones on the ground, lying supine and a little dizzy after a hike. Sky changing rapidly above, tie-dyed if you squint through the trees. Clouds crumbling like plaster. And that thing in the middle, a kind of inkblot betokening the inability of a genius to slow down, is like the black blotch you sometimes see after looking at the sun. There is a reflection of the eye in all this, but especially in that blotch and the way it also looks like a pupil, enlarged. Texture helps: the anti-leak channels of the pad become upper and lower lids. Green is nice for an iris. But then… there is the eerie feeling that, although it conforms to the notion of a landscape, and is hung like one, the eye in March sees nothing on the horizon.

Hardy, with her expected flair, has created in March a thickly layered pastiche in which the lessons of modernism as well as the ethics of pluralism are absorbed. This is a painting about art history that deserves to be called new, which is to say that it resists periodization.

– Sarah Nicole Prickett, Nicole Eisenman