Inquiring Nuns (1968), the American answer to Edgar Morin and Jean Rouch’s 1961 cinéma vérité classic Chronique d’un été, features two young nuns on the streets of Chicago, during the Summer of Love, disarmingly asking strangers, “Are you happy?” Not long after, the two sisters would leave their order to embrace secular life. The year the documentary came out is also when Corita Kent decided to leave the Order of the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Los Angeles, which she joined at the age of eighteen and where she remained for thirty years. By then, the charismatic “pop art nun,” educator, and activist had gained something of a celebrity status: the L.A. Times listed her among the “women of the year” in 1966, and the following year she appeared on the cover of Newsweek with the headline “The Nun: Going Modern.” Her deeply moving letter of resignation addressed to the mother superior and fellow members of the order, which would itself become a lay community in the ensuing decade, is exhibited in one of several vitrines presenting a judicious selection of archival materials and documents designed to contextualize Kent’s serigraphic output in her solo show at the Taxispalais Kunsthalle Tirol.

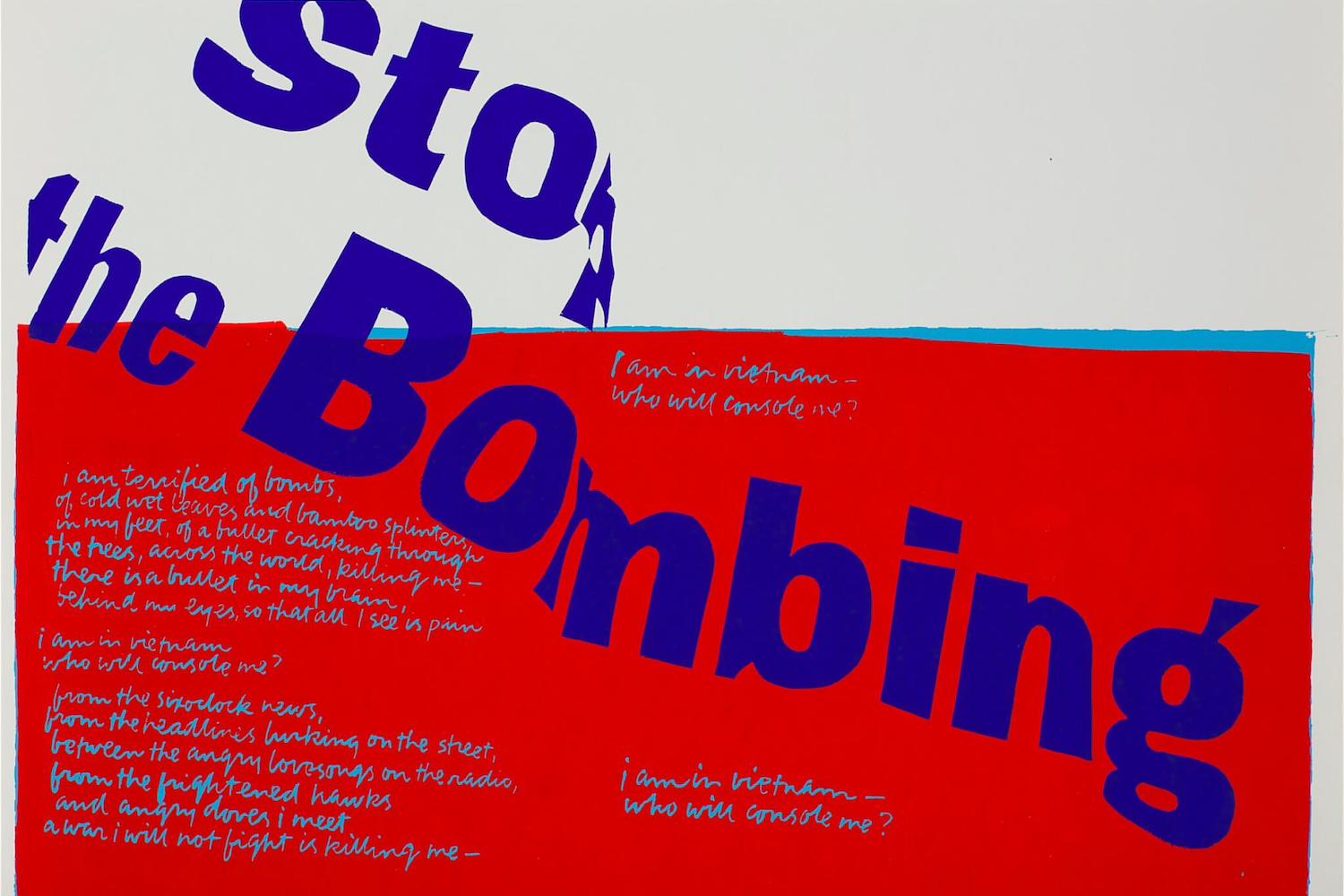

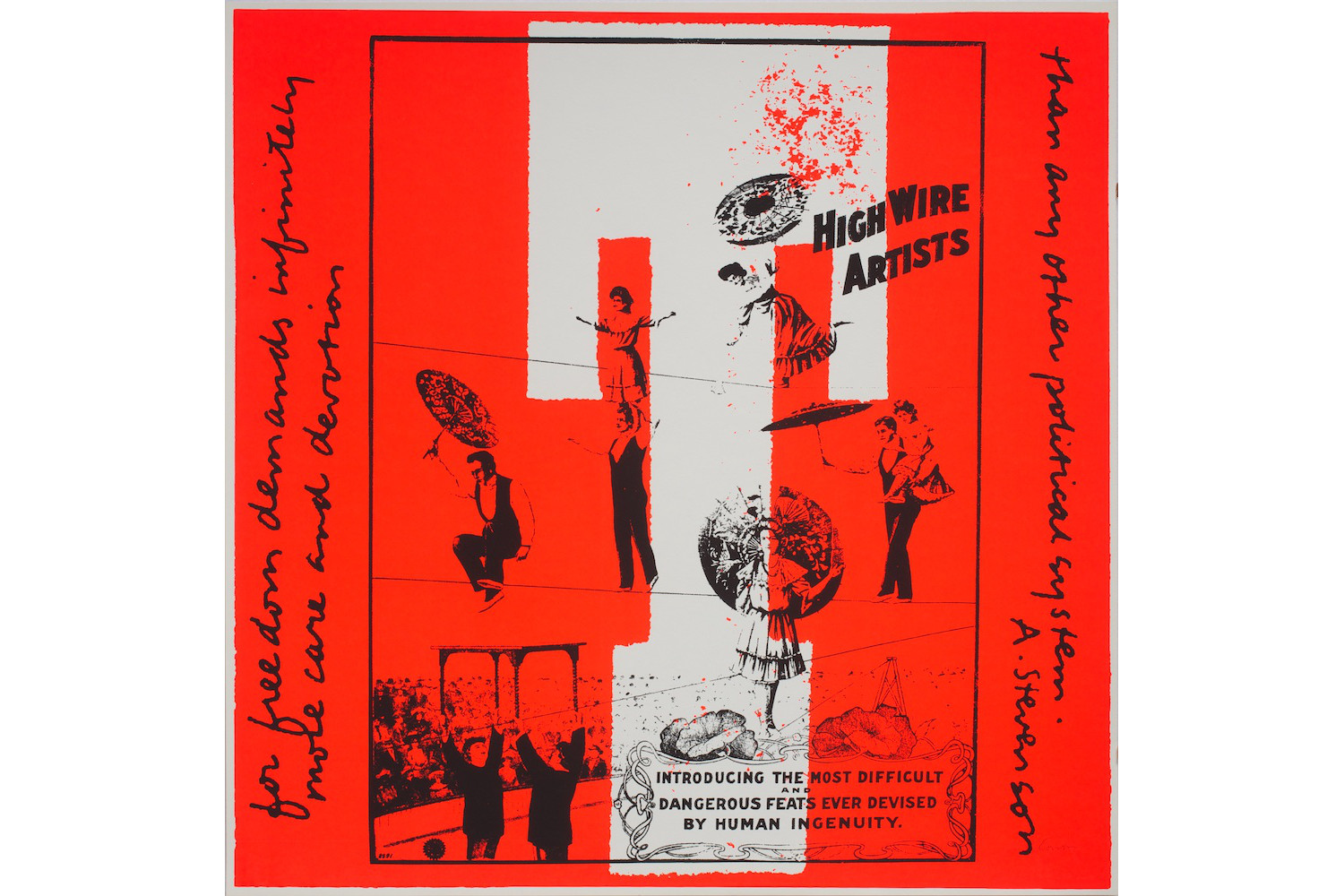

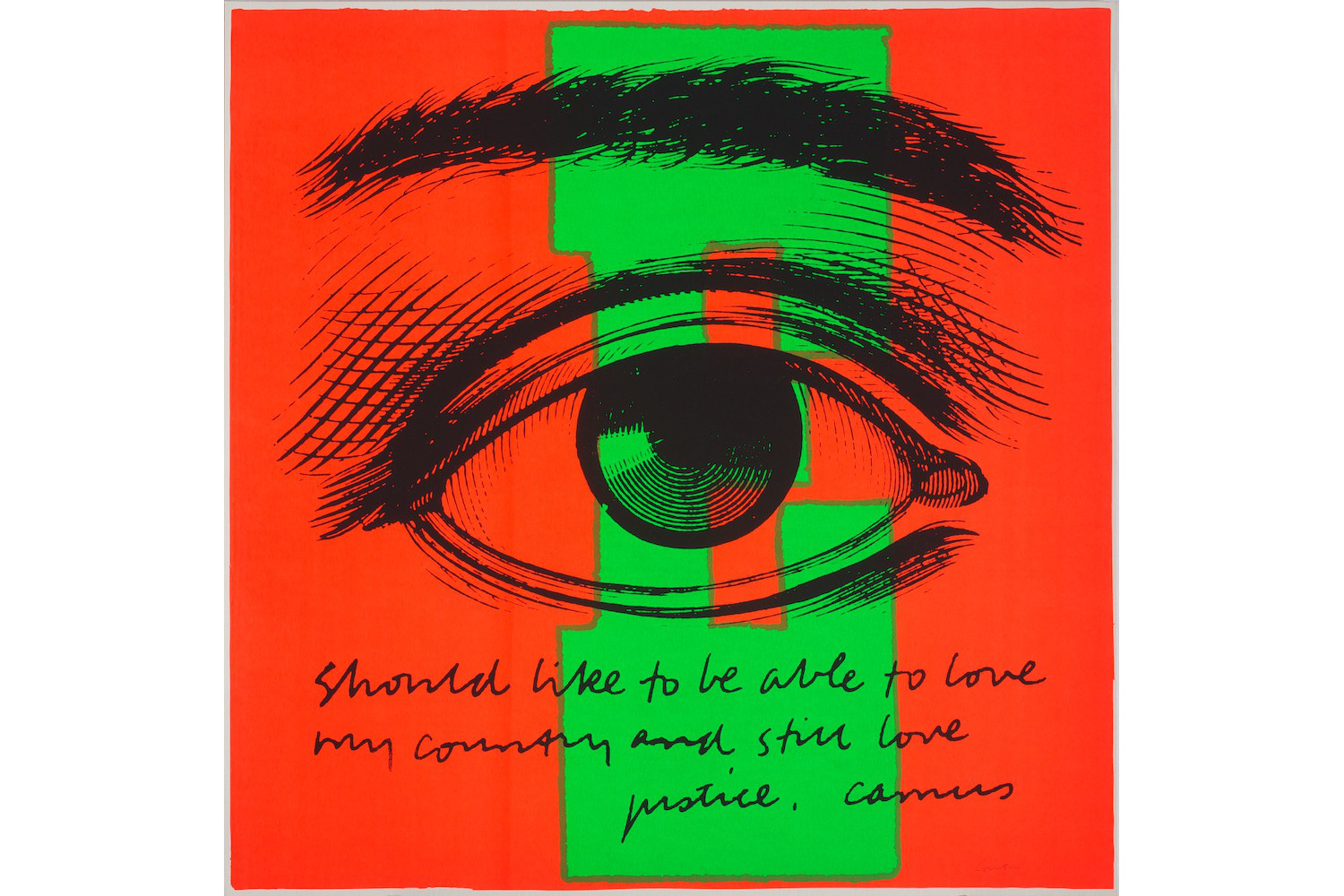

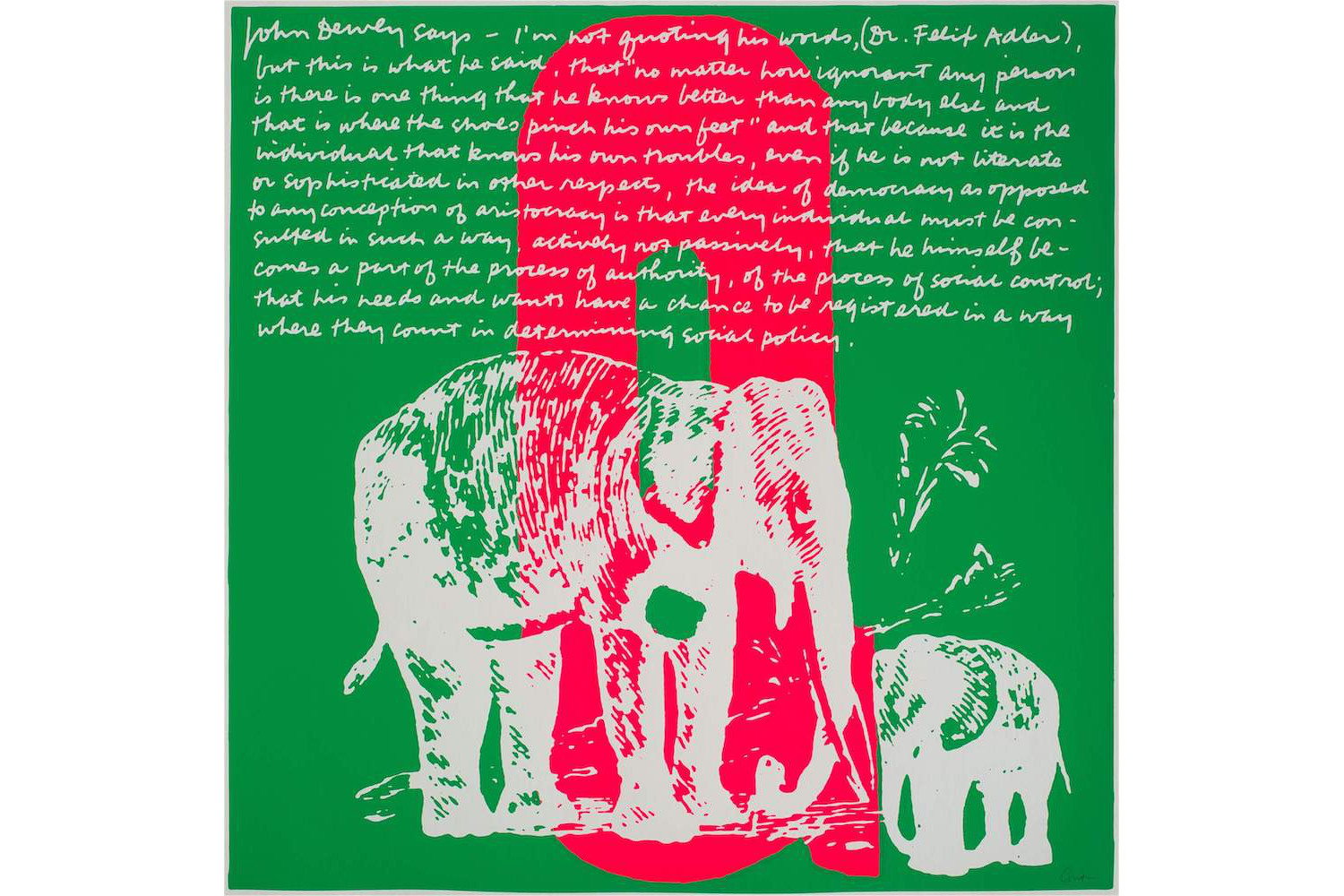

Spread over three gallery spaces, each painted a different primary color in keeping with Kent’s own bold chromatic range, “Joyful Revolutionary” focuses on her silkscreen production during the 1960s, charting the increasingly political turn of the artist’s work. The blue room at the start of the exhibition is given over to “Circus Alphabet” (1968), a series of twenty-six screen prints displayed in a neat row spanning two walls, their jarring fluorescent hues mounting an assault on the sense of vision. Inspired by a quotation from E. E. Cummings, one of Kent’s favorite poets and enduring influences, the series begins and ends with his programmatic statement “damn everything but the circus,” which appears in truncated form under the letter “A,” crops up again in W what every woman knows and is echoed in X give a damn. Each letter is center stage in the nearly square prints, overlaid with silkscreened images culled from Sarasota’s Ringling Circus Museum archive and American advertising books, as well as handwritten snippets and longer passages of poetry and prose, in a way that blurs the distinctions between text and image, background and foreground.

The red room next door shows Kent as a worthy representative of the Pop art movement, experimenting with advertising slogans, supermarket names, and household brands in her own distinctive manner, one that draws out their hidden Christian message. Sliced bread thus becomes a potent eucharistic symbol in Bread and Toast (1965); an oil company ad is recast so as to extoll the virtue of humility in We Care (1966); and Mary Does Laugh (1964) has the Mother of God shopping at the Market Basket, Sister Mary Corita’s local store, across the street from the Immaculate Heart College where she lived and — as of 1964 — headed the art department. Projected on monitor screens in dedicated spaces, two documentary shorts, by Thomas Conrad and Baylis Glascock respectively, both dating to 1967, offer insight into Kent’s pedagogical methods and the daily life of her religious community.

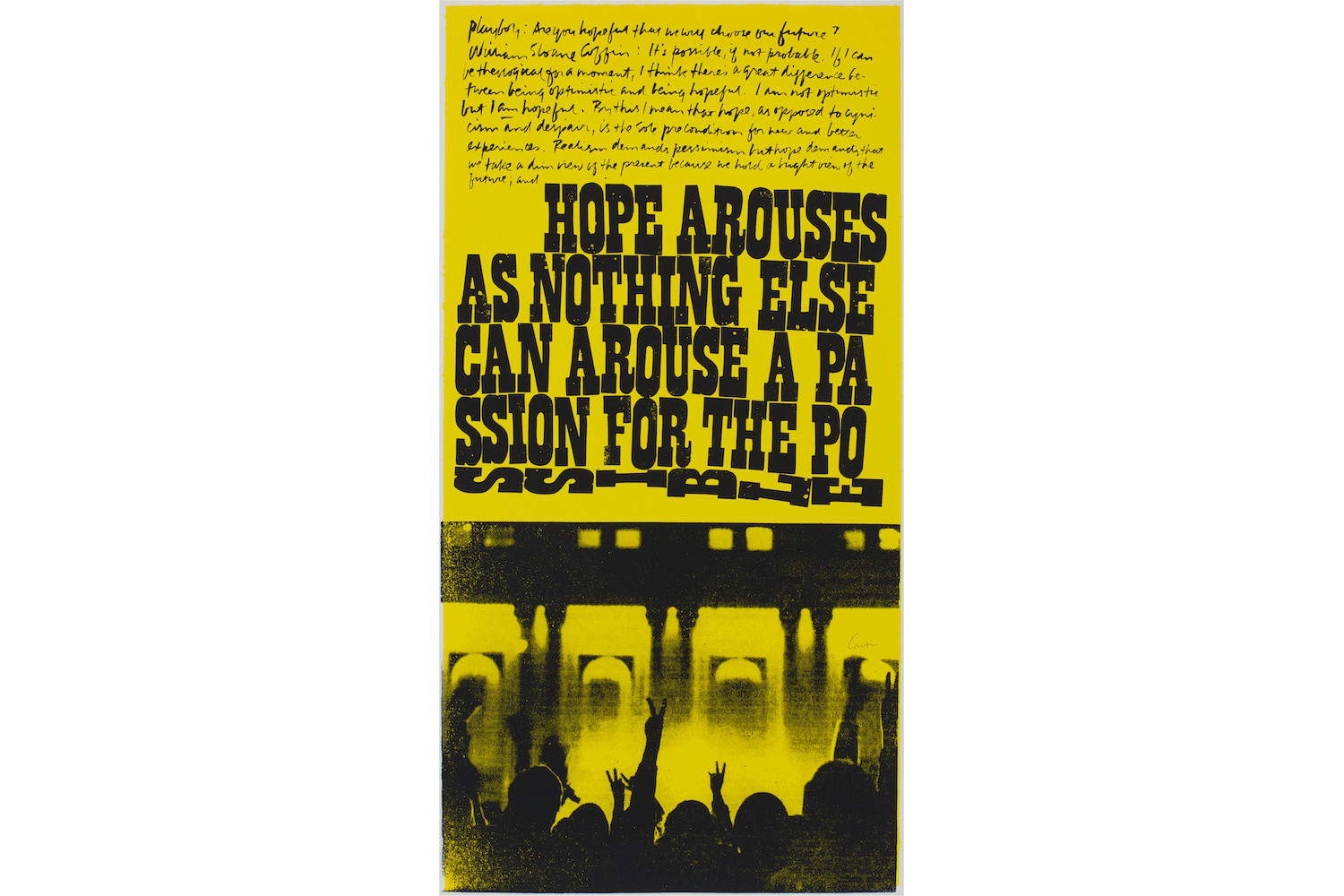

The main exhibition hall presents the earliest serigraphs featured in the show together with the “Heroes and Sheroes”series completed in 1969, after Kent had left the order and settled down in Boston. The political dimension comes to the fore in the latter series, where the artist adopts a new half-square format. The (mostly) vertical vignettes are mounted onto two facing walls painted a bright warm yellow for the occasion. Christ-like effigies and pietà figures lend an aura of martyrdom to portraits of poets and political and religious leaders, such as Henry David Thoreau, Martin Luther King, the Kennedy brothers, or the radical Catholic priests and peace activists Daniel and Philip Berrigan. These are accompanied by substantial quotations copied out in Kent’s distinctive hand. One wishes there were more instantly recognizable sheroes in their midst.