Ordinary humans do not live in their time; with their feeble instincts, they can only sense it. They live in a time already passed, a yesterday they know how to grasp and comprehend. Only a genius is predestined to sense the undercurrents of their epoch and experience them consciously. A true genius does not predict the future, but through discovering their time and objectifying it, creates a concept of new, future worlds.1

— Maria Jarema

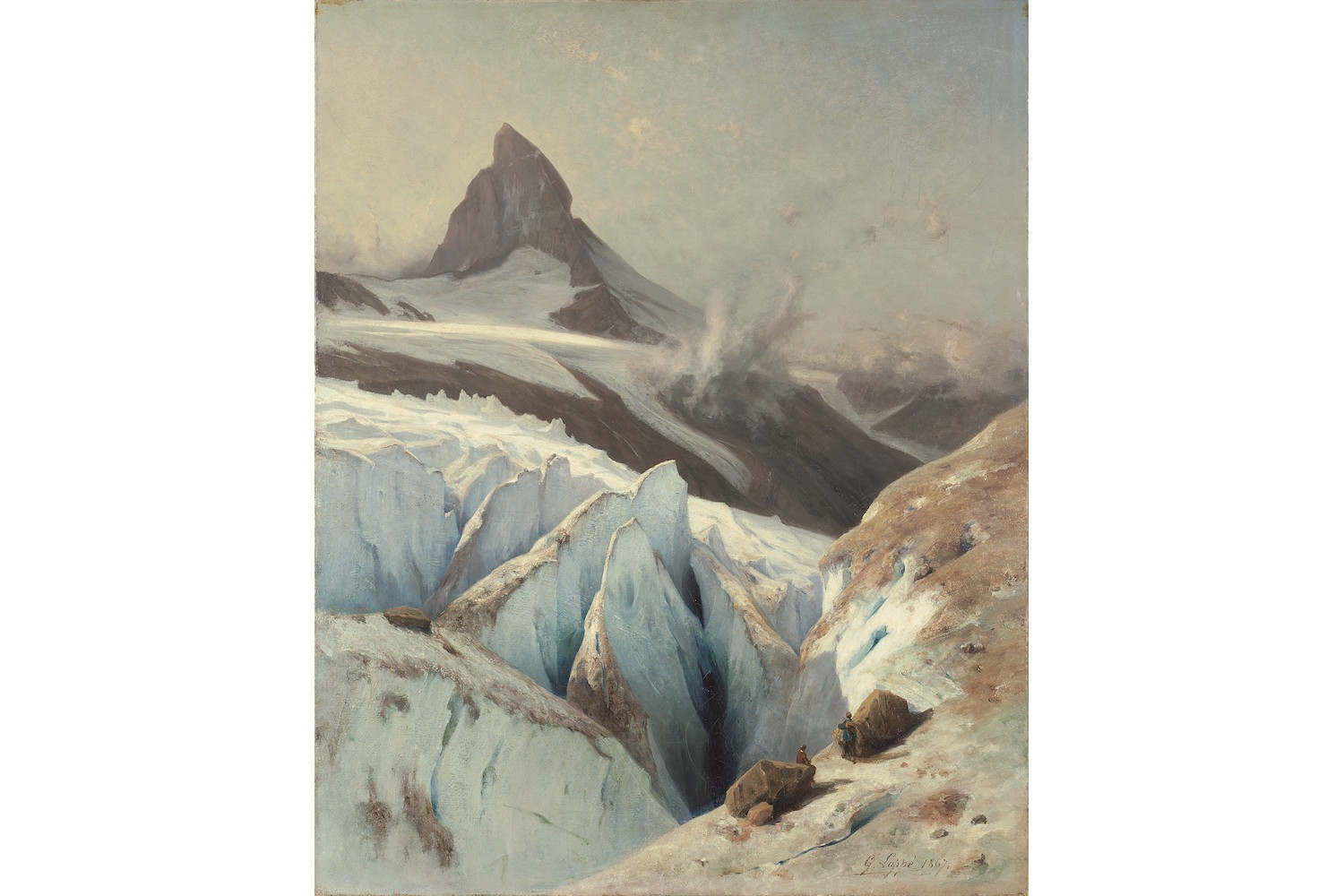

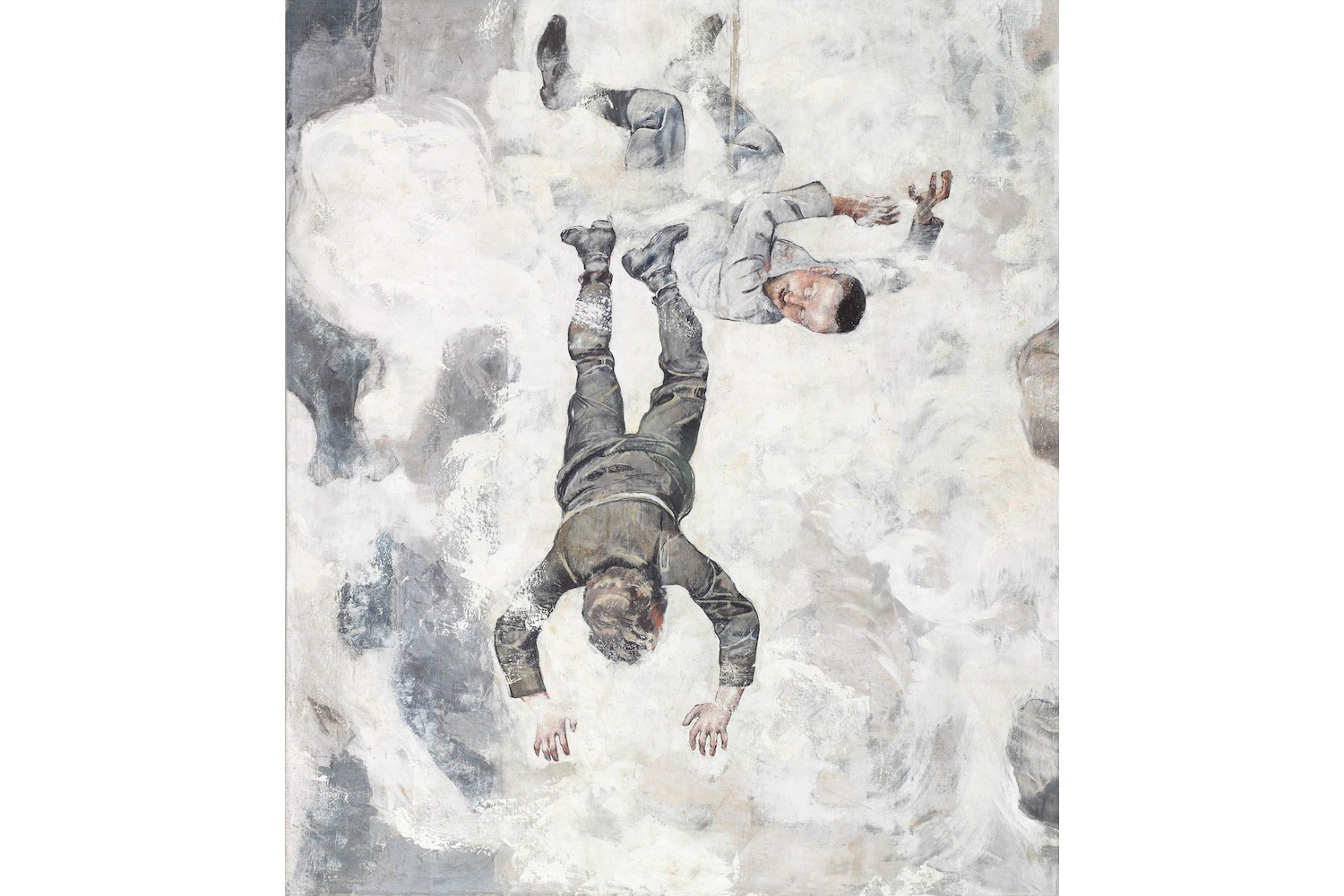

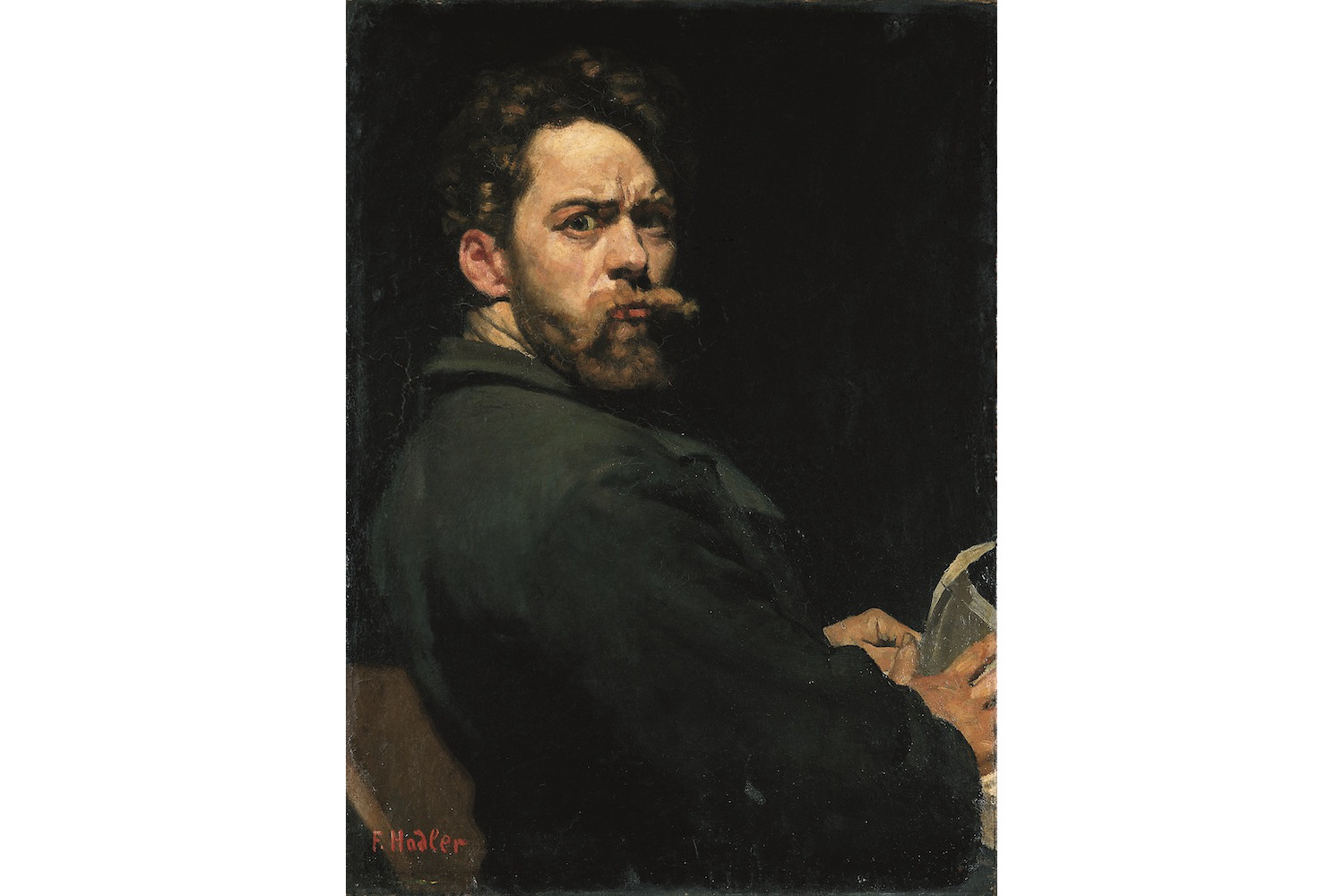

To write that the turn of the nineteenth into the twentieth century was a tumultuous period is a banal understatement: developments during this period led to the first military conflict on a global scale. In 1915, Félix Vallotton painted 1914, paysage de ruines et d’incendies (1914, A Landscape of Ruins and Fires), a striking depiction of a countryside engulfed in blood-colored flames and choked by thick fumes. Several years earlier, Ferdinand Hodler completed his breathtaking Aufstieg und Absturz (Ascent and Fall, 1894), a triumphant and tragic document of the first climb up the sublime yet treacherous Alpine peak the Matterhorn. In 1885, Clara von Rappard started working on Seele, Brahmane (nach Goethe)(Soul, Brahman (after Goethe), her self-portrait as a hybrid woman/dragon.

Even though “Alles zerfällt. Schweizer Kunst von Böcklin bis Vallotton” (Things Fall Apart: Swiss Art from Böcklin to Vallotton) at Kunstmuseum Bern takes as its point of departure a 1917 essay by Sigmund Freud, the three aforementioned artistic statements might act as metaphorical frames for this ambitious (both in its breadth as well as the depth of its concept) take on the institution’s extensive collection. The curatorial modus operandi is based on the assumption that a museum’s collection is not a static set of objects that carry a fixed set of meanings. To the contrary: by means of their anachronic 2 properties, a number of outstanding artworks in the exhibition can serve as mirrors in which the twenty-first-century beholder can see their own reflection, or messengers carrying past uncertainties into the comparably unstable present.

Freud’s “A Difficulty in the Path of Psycho-Analysis” describes the three humiliations that human narcissism underwent. The wounds inflicted by Copernicus, Darwin, and the self-proclaimed father of a new discipline, respectively, belittle the human animal, cruelly proving that he neither inhabits the center of the universe nor is God’s favorite, exceptional achievement. The coup de grace is delivered by Freud himself, who argues that the ego is (in opposition to the all-rational Cartesian subject) only a lonely island in the bottomless sea of the unconscious — a shattered, unstable, and inconsequential entity.

The exhibition itself unfolds in twelve thematic chapters, each detailing a different facet of our gradual fall from self-love as the human animal progressively forfeits its standing, yielding to nature, affect, and history. In landscape paintings by Elisée Jules Gustave Castan, depicting Switzerland’s monumental stone formations and forests, one witnesses the human figure losing significance and gaining humility. Castan’s works convey a new, post-romantic nature, which refuses to serve as a Stimmungslandschaft — an allegorical illustration of human emotions. Earth empathizes with man no longer. In a room dedicated to Adolf Wölfli, a space densely packed with the artist’s cryptic collages, ominous mandala-like drawings, and half-legible, erratic writings, one beholds the decline of reason in the face of the upcoming atrocities of war. A confrontation with historical events, experiences almost unimaginable in their scope and cruelty, are the subject of Valloton’s black-and-white graphic series C’est la guerre (This is War, 1915–16). Snapshots of events too intense, too barbarous to grasp in their entirety and to narrate in a single piece, are here metaphors of a fragmented nineteenth-century self.

This is how stories weave into history, and one cannot help but notice salient parallels with the present. The exact number of similarities with the tumultuous Jahrhundertwende are still to be decided; even though “Alles zerfällt” demonstrates that a past is never past, it also shows how open-ended yesterday’s stories may be.