It’s a match made in heaven (to invoke the customary idiomatic phrase) between two artists whose practices are so compatible — as much in their affinities as in their distinctive divergences — that it seems crazy no one thought of pairing them before. An additional bravo, therefore, goes to the Belgian pied-à-terre shared by four exhibition spaces scattered across the globe: Park View/Paul Soto (Los Angeles), Lulu (Mexico City), LambdaLambdaLamda (Prishtina, Kosovo), and Misako & Rosen (Tokyo). Normally they take turns behind the wheel in Brussels, but this intergenerational presentation was jointly organized.

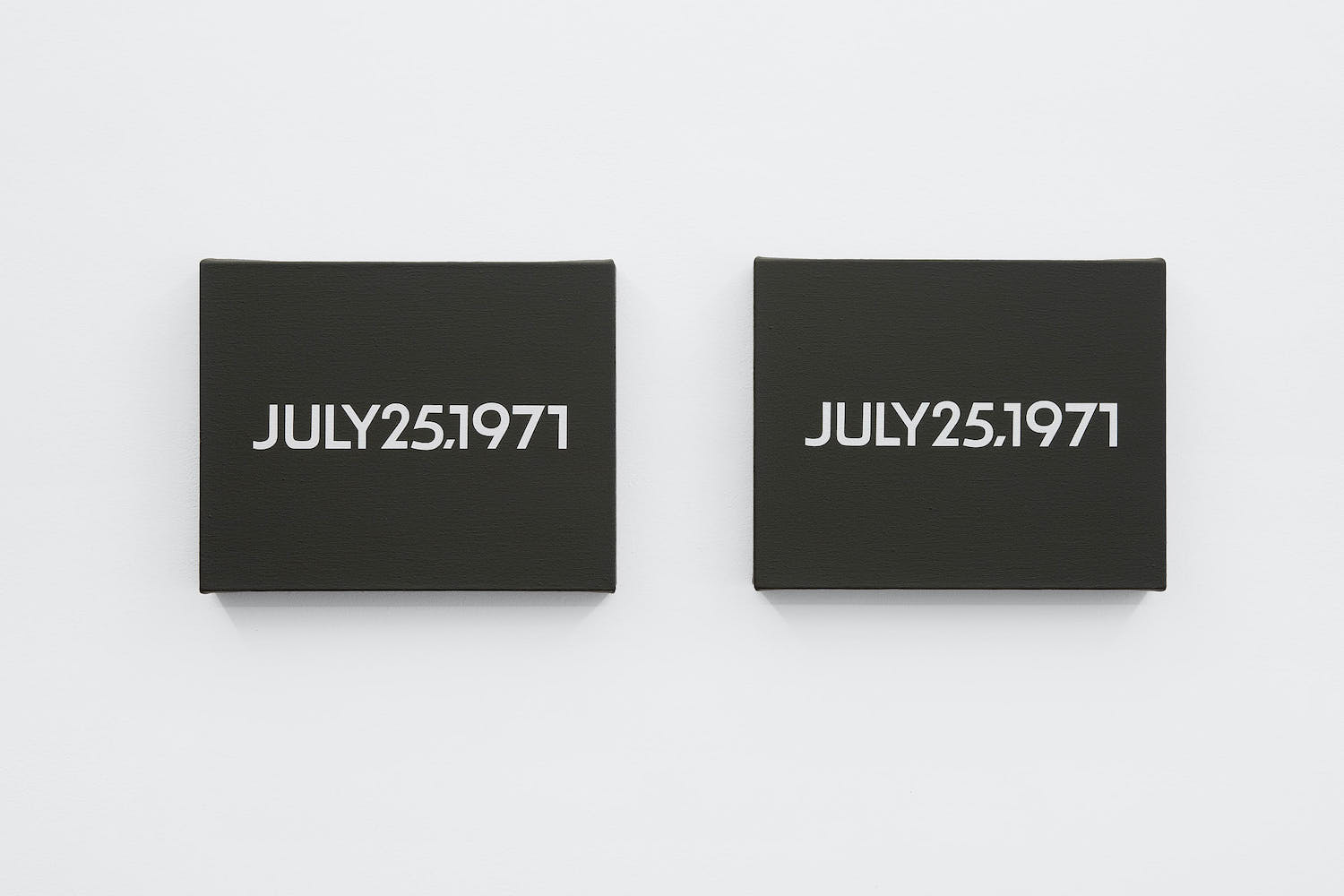

The elusive conceptualist On Kawara (1932–2014) is represented by two specimens from his famous “Today” series begun in 1966 and conceived to extend for the artist’s lifespan. For each one, Kawara painted — with a meticulousness mimicking industrial production — that day’s date in white lettering on a monochrome field, taking into account the linguistic conventions of the place where the particular work was carried out (one hundred cities total, give or take). Any paintings that were still unfinished when the portrayed date was past were destroyed, which gives a certain cornucopian novelty to the diptych presented — two pieces dated 25 July 1971.

Kawara’s ancillary activities to the paintings — recording their details in a journal and storing them with a clipping from a local newspaper bearing the same date — have acquired increasing attention among his aficionados. Viewers may well wonder what headlines occupied the front page of the New York Times on the date in question. That Kawara was featured on the cover of the July 1971 issue of Flash Art is also a notable coincidence.

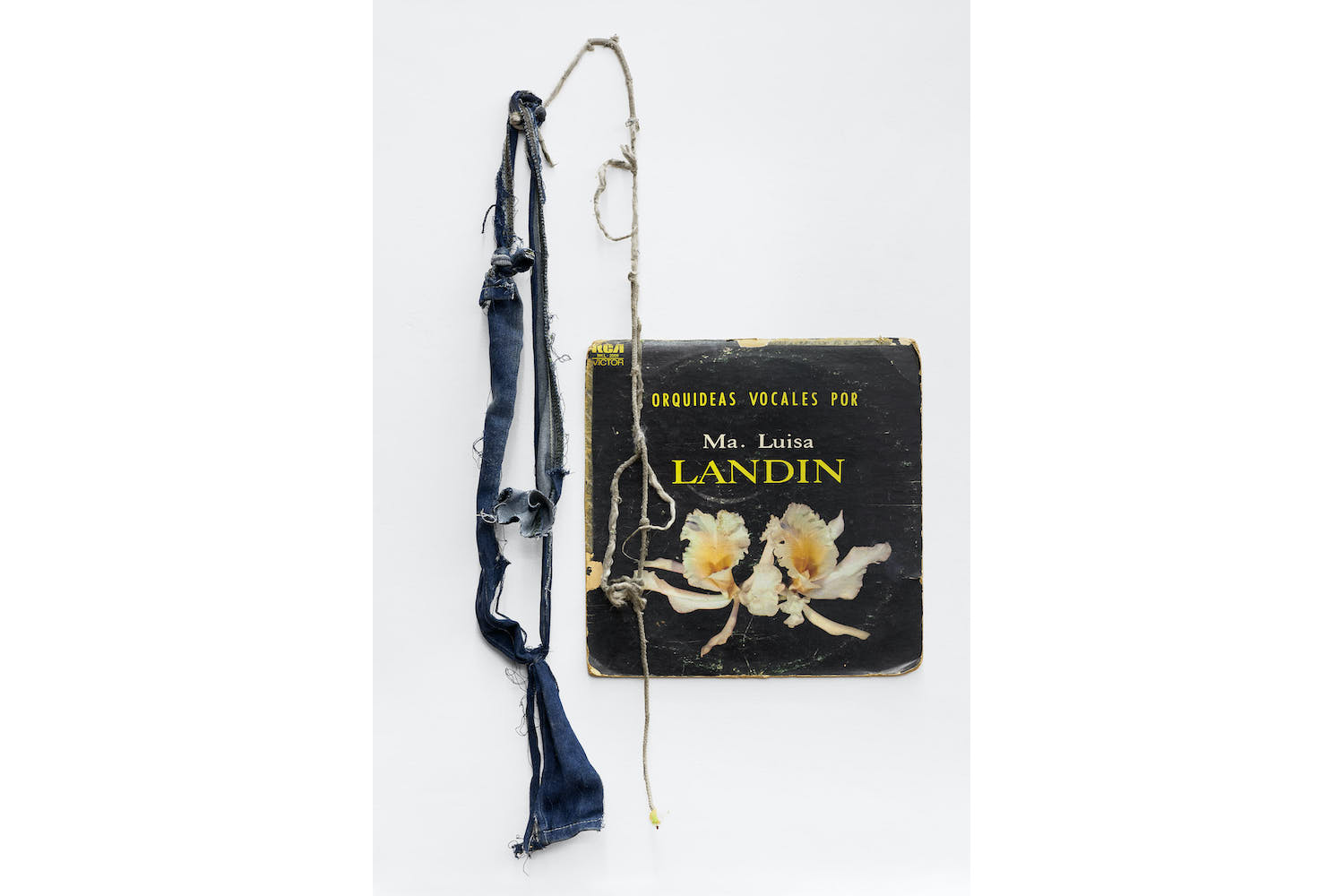

Yuji Agematsu (b. 1956), for his part, moved to New York in the 1980s to study under jazz drummer extraordinaire Milford Graves, after completing his apprenticeship with Tokio Hasegawa of the legendary experimental music ensemble the Taj Mahal Travellers. Soon he started to wander the city — taking notes, sketching trajectories, picking up objects that captured his attention. At first it was simply to get acquainted with the new urban landscape, but soon enough, the promenades became the very core of his days. Found residue, debris, and plain garbage morphed into objects of sculptural value. Agematsu arranged his tiny, delicate compositions in the plastic wrappers of cigarette packs. Some of the works on display in this exhibition come from a two-week residency in Mexico City, bringing to light a formerly hidden connection: Mexico City was On Kawara’s first landing place after leaving Japan with his father. Regardless of the instinctive reaction that the materials can induce in the viewer (from curiosity to repulsion), the assemblages reveal a punctual exercise, the mastery of an alien methodology, and a compositional acumen that neutralizes any potential reception of the work as solely the precipitate of a process.

Both artists establish subtle relationships with time and its passage. They condense it, encapsulate it, index it. Kawara’s paintings are self-portraits in which the artist’s features atrophy into a pure mark of his existence at a given moment (“still alive” is a refrain in his other series as well). The traces of Agematsu’s days are normally presented in vitrine-like, orderly shelf arrangements like sculptural approximations of calendars. But they also deal with labor. Better: with the meaning of “work” in “artwork.” At a moment when art’s pictorial, and in general “heroic,” connotations were being radically questioned, the “Today” paintings absorb almost entirely and explicitly the amount of work necessary to carry them out. They standardize as much as possible the rules of execution in a seductive game (concerning the single works, never the series) with the idea of fungible commodity.

For his part, Agematsu may look like a flaneur, the Baudelairian dandy strolling aimlessly through the city for a variety of reasons: to deplete the most precious resource of a human life; to treasure volatile, prismatic impressions to be molded into poetry; to resist “productive work,” that infamous mark of the bourgeoisie. Only the German philosopher Walter Benjamin, in his enamored ruminations on the French capital, hinted at the fact that the bohemian wandered (also) in an indirect assonance with the siren song of shiny commercial goods, then being displayed in increasingly seductive configurations in the streets, the arcades, the department stores. In short, the flaneur was an unaware antecedent of the consumer to come. Agematsu’s work — beautiful as it is — sings a song of waste, of the left behind.

La Maison de Rendez Vous takes its name from a breakneck noirish novel by the nouveau roman exponent Alain Robbe-Grillet. I suspect that on very few occasions before the exhibition space have been so germane to the text in its incessant multiplication of impalpable clues and undeniable formal charm.