COVID-19 is tipping the world into a dangerously volatile new era. People everywhere are being forced to step outside their “usual life” for their own sake; many are freed from commuting to work and can watch as much TV as they want, yet they are still confined to a particular space and time. Fost Gallery’s online exhibition “Come Together” presents a unique opportunity to experience with others the prospect of getting away from what you usually are. In response to a growing sense of rootlessness, disillusionment, pessimism, and dread, twelve artists from Asia find consolation in metaphysics and “inner understanding.”

Indeed, simply getting together sometimes seems to be enough. Here the artists gather in an art-world version of “people meeting people,” albeit virtually. From wherever they are in the world, they talk about and connect to each other’s work, negotiating the tensions that affect their art during “life in lockdown.” In John Clang’s Portrait of an Invisible Enemy (1) (2020), a man with a large cloak over his head wanders in a mysterious background, drawing a surreal parallel to face-mask-wearing citizens on deserted streets. Clang’s photographic print suggests a prolonged, silent combat — the struggle of the individual against the virus, a battle between the invisible and the human.

As it is, scientists around the world are racing to develop vaccines against COVID-19, and countries are charting the pandemic to keep track of the numbers. As Friedrich Nietzsche wrote: “Science explains the course of nature, but can never give man commands. Inclination, love, pleasure, pain, exaltation, exhaustion — science knows nothing of all this. What man lives and experiences, he must interpret, and thus evaluate, on some basis.”1

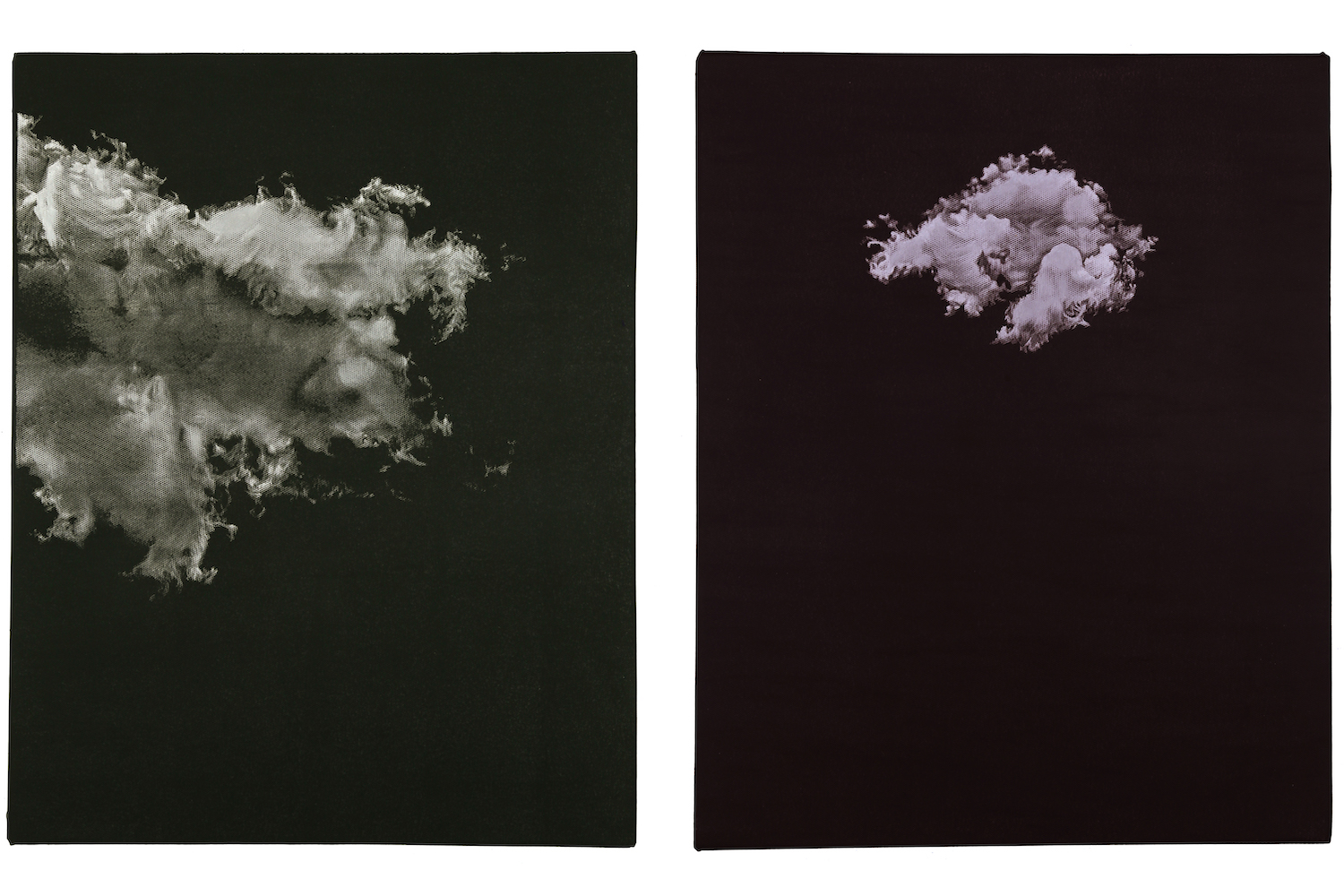

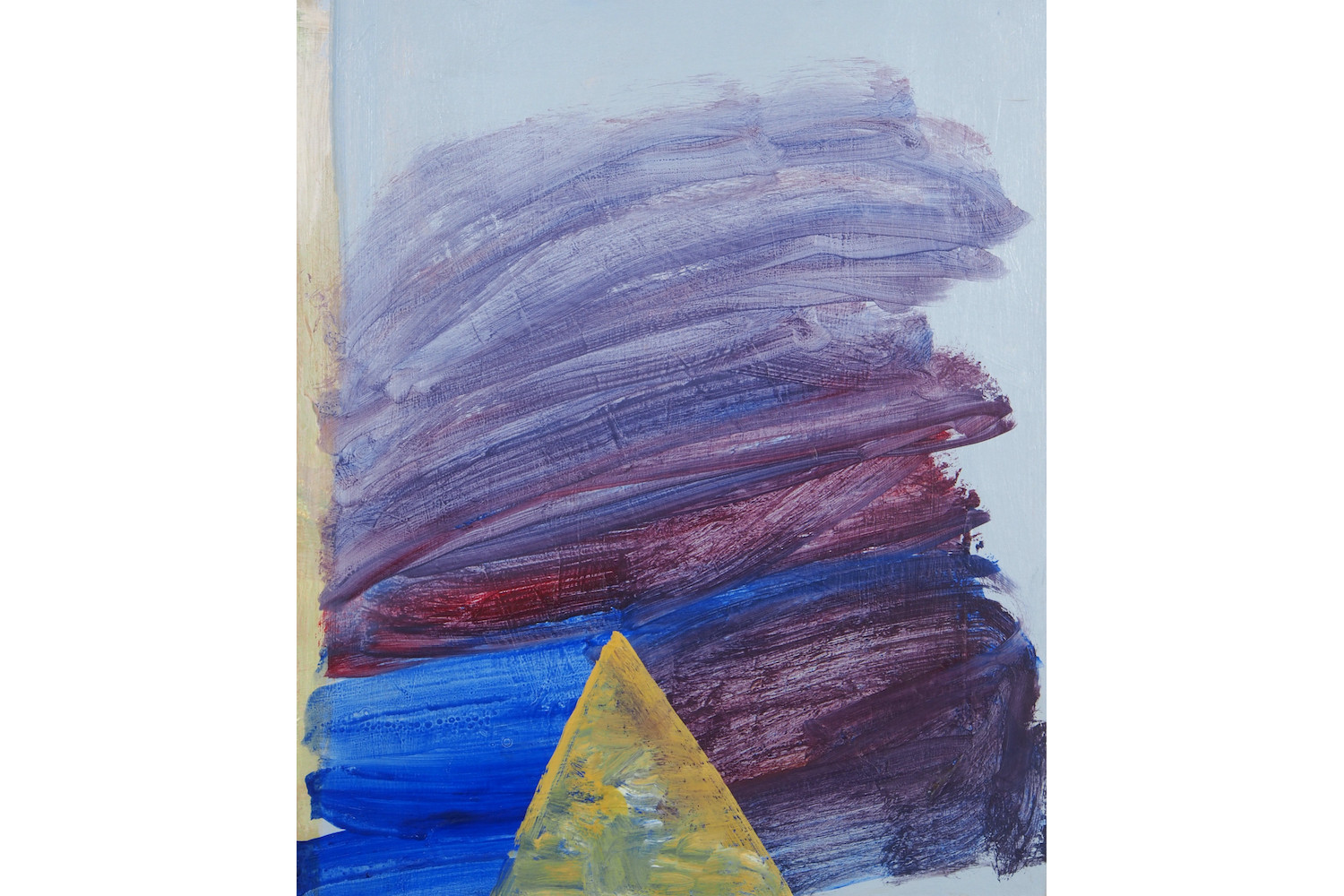

Other works also juxtapose the strangeness of the aesthetic object with current events. Donna Ong’s dreamlike photomontages portray tropical forests from colonial times to the present day. Adeel uz Zafar’s instinctual response takes the form of distant, cloudlike apparitions. His diptych Ascension (2017) shows these celestial bodies suspended in a black, undefined space. Wyn-Lyn Tan’s Blush/Anti-Matter (2020) and Ian Woo’s Lightness Path 2 and Lightness Path 9 (both 2016–17) place emphasis on a high degree of abstraction — perhaps the only approach that is able to provide a vision that transcends the everyday.

Elsewhere, subtle resonances are drawn out between works that take social bonding as their subject matter. John Clang’s Being Together (2010) uses video technology to take photographs of families who live apart, while Bovey Lee’s Roots (2014) features a beautiful, intricate paper cut-out that evokes the difficult web of life’s relationships. Importantly, dialogue and social interactions are in the foreground of this exhibition because they are scarce elsewhere. For example, Ian Woo talks about Kray Chen’s work, John Clang about Ezzam Rahman’s, and so forth. The idea of community is conveyed too in Kray Chen’s two-channel video Every Good Body Dances (2019), which shows five musicians riffing on the Baltic folk pop song “Yesterday I Went to the Village Priest” at different speeds, with eight dancers moving in a circle, oblivious to the tempo changes. Is the work about how people deal with change? “Come Together” speaks to a sensitive contemporary moment with a sort of mushrooming of understanding. I applaud these individuals who respond deeply and subjectively to what is happening around us.