“Public Art 2666” is a column that seeks to explore the interaction between the public domain and contemporary artistic practices, giving particular consideration to the resulting social impacts. The research is run by Collettivo 2666.

“Until video is used as indifferently as the telephone, it will remain a pretentious curiosity.” Thus concludes Allan Kaprow’s 1974 essay Video Art: Old Wine, New Bottle. While more concerned with the public’s participation in video’s early, often solemn appearance in the art gallery,1 by mentioning the indifference towards mass, accessible communication media, Kaprow evokes the contrasting enthusiasm and politicized energy with which many greeted video as the first “live” medium, championing its potential for broadcasting “counter-information”2 horizontally, bypassing a top down network.

At the turn of the last century video artist and scholar Simonetta Fadda declared that “video is the language of contemporaneity, the vehicle of modern sense perception”.3 This is true now more than ever before. It is precisely the question of indifference in this regard that the subsequent contributions to this thread of Public Art 2666 seek to address.

The irony is not lost on us that we are launching this discussion on art in the public sphere at a moment when occupying public space in many states across the globe is fraught, perhaps even illegal, imbued with danger or, at the very least, anxiety. While undermining our ability to congregate in public space – to participate, as Kaprow might say4 – have we sufficiently politicized private space?

At this point taking an “indifferent” attitude toward video would be akin to political indifference in general. When pressed to distinguish video from its antecedent film we suggest: video is private, film is communal. Video is divorced from a specific architecture and a specific collective experience. Video, from the Latin “I see” entered into English in 1935 as a visual equivalent of the word “audio”. As a noun it means “that which is displayed on a (television) screen).5 By video we mean anything that can be shared on a screen, electronically, from an I to an I, while also referring to the entire apparatus that makes such a phenomenon possible. As Sean Cubitt writes in Videography,6 video is “at the heart of the increasingly interlinked webs of previously separate media… There is no essential form of video, nothing to which one can point as the primal source or goal of video activity”(p.xv). This is why Cubitt uses the term “video media” to mean any practice that involves the recording of an event, the potential for its preservation, but also the potential to broadcast it, live. Along these lines, his use of the term recalls

Gene Youngblood’s concept of the videosphere,7 perhaps the ideal metaphor for such an all-encompassing combination of broadcast/live and record/archive whereby its meaning can now extend to include social media as well.

Ways of rethinking public space in light of recent developments of media include Pier Luigi Sacco’s reference to television as “l’altro grande spazio pubblico,” [“the other great public space”] to Cecilia Guida’s Spatial practices8 wherein she coins the term “postpubblico” as a “situation” where actors in real cities and streets interact with those online, creating one in which the borders between real and virtual become indefinite and porous”.9 Amidst the extreme shift of the past months, the videosphere and the public sphere have effectively overlapped. There has been an eclipse.

Conceived as such, video art is the perfect place to start questioning public art. It is no coincidence that Vito Acconci, one of the pioneers of early performance based video art in NY, would turn to a more public art practice later in his career following video’s early experimental heyday. Likewise, it is no coincidence that video art emerges at the same time that the notion of an “End of the History of Art” (Belting, 1983) percolates with the greatest intensity in the popular consciousness; after all, according to Umberto Eco, well before the advent of the internet, the proliferation of television and its inherent simultaneity led to the loss of a sense of history.10 Fully perceptible by the mid-1970s this sense is precisely what defines the transition from Modern to Contemporary Art,11 in which video can therefore be said to have a fulcral role.12 It should primarily be understood as the inability of any particular formal quality to form an overarching, hegemonic tradition precisely because of the increasing “presence”, or availability, of the past.

Mario Perniola, who identifies as a philosopher whose thought priviledges the present,13 calls this the “Egyptian” moment, given what he perceives as the tendency in the ancient civilization’s visual culture to nullify the old and the new into one single temporal dimension, placing them side by side and leaving the contradictions that arise open to interpretation,14 consonant, in a way, with Hermine Freed’s statement regarding her 1973 tape Family Album that “its structure and organization are arranged as a composition in time on the one hand, and a metaphor for memory on the other. Past collides with present, present is superimposed on past.”15

We seek to investigate video art as it informs digital culture, especially in so far as “post-public” or “other public” spaces can exist and what role art has within them.16 While the transmutation of analog video tapes into digital files is often overlooked as a mere device of preservation,17 we view this transfer as an evolution, or rather as a transito,18 in digital media’s lineage, the roots of which, it follows, can be traced back to analogue video through an exploration of the ways in which its surrounding practices anticipate those of social media. It is considered one of the revolutionary aspects of the advent of the internet that it brought about, for the first time, the possibility that “every receiver of information could be a producer, or at least a transmitter of information and ideas.”19 While this is indeed a key feature of current digital culture, we will also explore the extent to which the video recorder, invented some 30 years prior, enables precisely this forming of a “net” of users, simultaneously recording and broadcasting with whoever else has similar technology, with a focus on how artists and writers at the time engaged with this potential. As art critic Marco Meneguzzo writes, “going back in time until the seventies one finds something similar to the diffusion of the internet in the moment of video recorder’s boom.”20 Maybe artists are “antennae” of the human race after all?

While it indeed remained, as Kaprow warned, a “pretentious curiosity” to some, for others such as Luciano Giaccari, operating in the long-lingering shadow of the 1968 student revolt and its political tension provided fertile ground for forms of “artivism” where video’s potential for “counter-information” could pass from operator/viewer to operator/viewer in the newly formed “net”, horizontally bypassing studio production with a vibrant enthusiasm compared to the relatively apathetic attitude regarding technology in today’s “panorama postideologico”.21 One of his fundamental principles, made obvious in his rigorous 1973 Classification… of video’s use in the artworld, was to consider the (video) artist’s activity, by definition, to be without limits. By studying artists’ use of it, perhaps we can better understand the limits we impose on our own use of this technology today, especially with regard to its prevalence in, or as, the public sphere?

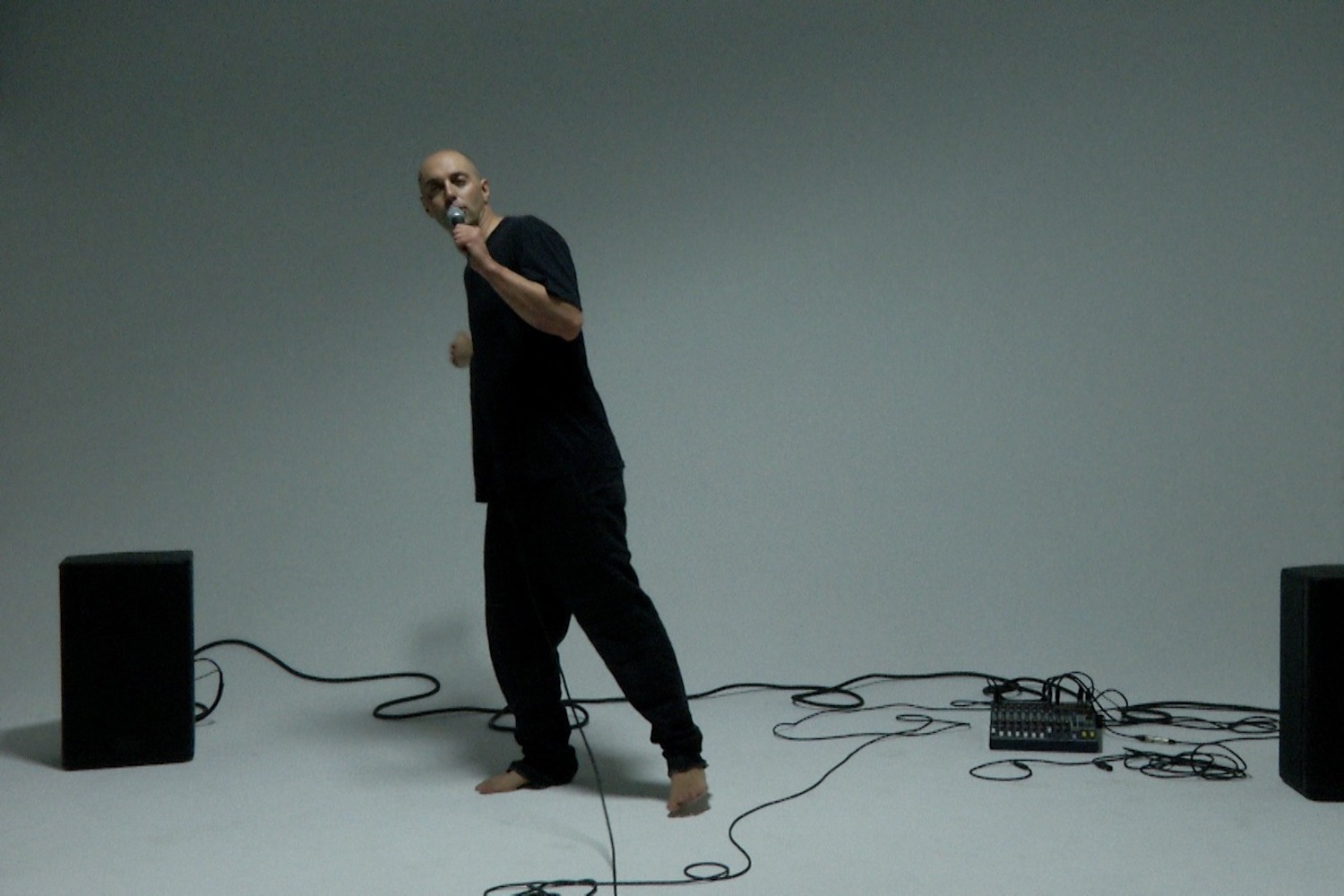

To what extent are Youtube videos are another heir of video art? Does the 24-hour livestream performance from Nico Vascellari to launch CODALUNGA on YouTube from May 2–3, 2020 owe much to Giaccari’s 1968’s Televisione come memoria ?

Regardless, these raise our driving question: what are the implications when public art is video art?